Interviewees - Ventura Unified School District

advertisement

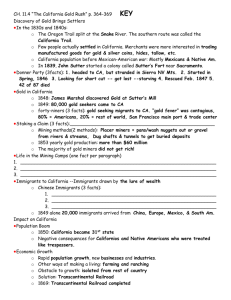

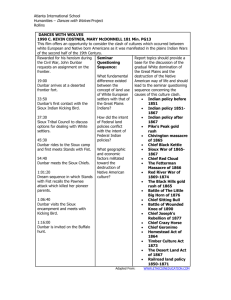

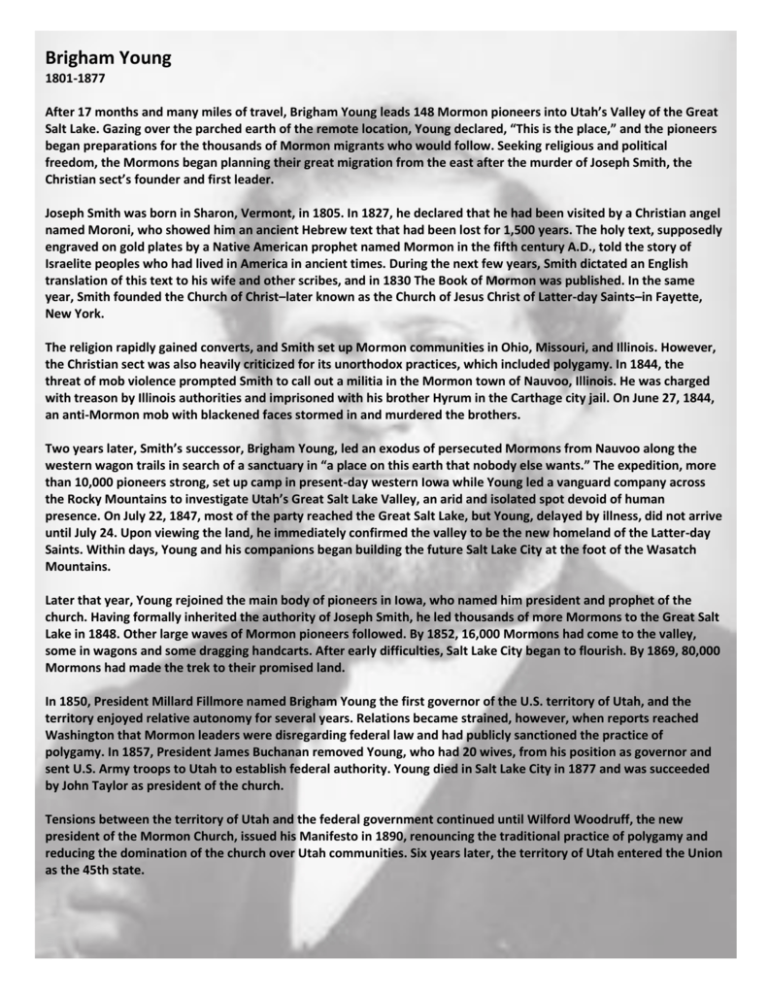

Brigham Young 1801-1877 After 17 months and many miles of travel, Brigham Young leads 148 Mormon pioneers into Utah’s Valley of the Great Salt Lake. Gazing over the parched earth of the remote location, Young declared, “This is the place,” and the pioneers began preparations for the thousands of Mormon migrants who would follow. Seeking religious and political freedom, the Mormons began planning their great migration from the east after the murder of Joseph Smith, the Christian sect’s founder and first leader. Joseph Smith was born in Sharon, Vermont, in 1805. In 1827, he declared that he had been visited by a Christian angel named Moroni, who showed him an ancient Hebrew text that had been lost for 1,500 years. The holy text, supposedly engraved on gold plates by a Native American prophet named Mormon in the fifth century A.D., told the story of Israelite peoples who had lived in America in ancient times. During the next few years, Smith dictated an English translation of this text to his wife and other scribes, and in 1830 The Book of Mormon was published. In the same year, Smith founded the Church of Christ–later known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints–in Fayette, New York. The religion rapidly gained converts, and Smith set up Mormon communities in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. However, the Christian sect was also heavily criticized for its unorthodox practices, which included polygamy. In 1844, the threat of mob violence prompted Smith to call out a militia in the Mormon town of Nauvoo, Illinois. He was charged with treason by Illinois authorities and imprisoned with his brother Hyrum in the Carthage city jail. On June 27, 1844, an anti-Mormon mob with blackened faces stormed in and murdered the brothers. Two years later, Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, led an exodus of persecuted Mormons from Nauvoo along the western wagon trails in search of a sanctuary in “a place on this earth that nobody else wants.” The expedition, more than 10,000 pioneers strong, set up camp in present-day western Iowa while Young led a vanguard company across the Rocky Mountains to investigate Utah’s Great Salt Lake Valley, an arid and isolated spot devoid of human presence. On July 22, 1847, most of the party reached the Great Salt Lake, but Young, delayed by illness, did not arrive until July 24. Upon viewing the land, he immediately confirmed the valley to be the new homeland of the Latter-day Saints. Within days, Young and his companions began building the future Salt Lake City at the foot of the Wasatch Mountains. Later that year, Young rejoined the main body of pioneers in Iowa, who named him president and prophet of the church. Having formally inherited the authority of Joseph Smith, he led thousands of more Mormons to the Great Salt Lake in 1848. Other large waves of Mormon pioneers followed. By 1852, 16,000 Mormons had come to the valley, some in wagons and some dragging handcarts. After early difficulties, Salt Lake City began to flourish. By 1869, 80,000 Mormons had made the trek to their promised land. In 1850, President Millard Fillmore named Brigham Young the first governor of the U.S. territory of Utah, and the territory enjoyed relative autonomy for several years. Relations became strained, however, when reports reached Washington that Mormon leaders were disregarding federal law and had publicly sanctioned the practice of polygamy. In 1857, President James Buchanan removed Young, who had 20 wives, from his position as governor and sent U.S. Army troops to Utah to establish federal authority. Young died in Salt Lake City in 1877 and was succeeded by John Taylor as president of the church. Tensions between the territory of Utah and the federal government continued until Wilford Woodruff, the new president of the Mormon Church, issued his Manifesto in 1890, renouncing the traditional practice of polygamy and reducing the domination of the church over Utah communities. Six years later, the territory of Utah entered the Union as the 45th state. Davy Crockett 1786-1836 Davy Crockett was born on August 17, 1786, in Greene County, Tennessee. In 1813, he participated in a massacre against the Creek at Tallushatchee. In 1826, he earned a seat in the 21st U.S. Congress. He was re-elected to Congress twice before leaving politics to fight in the Texas Revolution. On March 6, 1836, Crockett was killed at the Battle of the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. Davy Crockett was born as David Crockett on August 17, 1786, in Greene County, Tennessee. He was the fifth of nine children born to parents John and Rebecca (Hawkins) Crockett. Crockett's father taught him to shoot a rifle when he was just 8 years old. As a youngster, he eagerly accompanied his older brothers on hunting trips. But, when he turned 13, his father insisted that he enroll in school. After only four days of attendance, Crockett "whupped the tar" out of the class bully and was afraid to go back lest he face punishment or revenge. Instead, he ran away from home and spent the next three years wandering, while honing his skills as a woodsman. Just before he turned 16, Crockett went home and helped work off his father's debt to a man named John Kennedy. After the debt was paid, he continued working for Kennedy. At just a day shy of 20, Crockett married Mary Finley. The couple would bear two sons and a daughter before Mary died and Crockett remarried to Elizabeth Patton, who gave him another two children. In 1813, after the War of 1812 broke out, Crockett signed up to be a scout in the militia under Major John Gibson. Stationed in Winchester, Tennessee, Crockett joined a mission to seek revenge for the Creek Indians’ earlier attack on Fort Mims, Alabama. In November of that year, the militia massacred the Indians' town of Tallushatchee, Alabama. When his enlistment period for the Creek Indian War was up, he re-enlisted, this time as a third sergeant under Captain John Cowan. Crockett was discharged as a fourth sergeant in 1815, and went home to his family in Tennessee. Back at home, Crockett became a member of the Tennessee State House of Representatives from 1821 to 1823. In 1825, he ran for the 19th U.S. Congress, but lost. Running as a Jacksonian candidate in 1826, Crockett earned a seat in the 20th U.S. Congress. In March of 1829, he changed his political stance to anti-Jacksonian and was re-elected to the 21st Congress. In the next election, he failed to garner a seat in the 22nd Congress. He was, however, elected to the 23rd Congress in 1833. Crockett's stint in Congress concluded in 1835, after his run for re-election to the 24th Congress ended in defeat. During his political career, Crockett developed a reputation as a frontiersman that, while at times exaggerated, elevated him to folk legend status. While Crockett was indeed a skilled woodsman, his notability as a Herculean, rebellious, sharpshooting, tale-spinning and larger-than-life frontiersman was at least partially a product of his efforts to package himself and win votes during his political campaigns. The strategy proved largely effective; his fame helped him defeat the incumbent candidate in his 1833 bid for re-election to Congress. After Crockett lost the 1835 congressional election, he grew disillusioned with politics and decided to join the fight in the Texas War of Independence. On March 6, 1836, he was killed at the Battle of the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. While the exact cause of Crockett's death is unknown, Peña, a lieutenant on the scene, stated that Crockett and his comrades at arms died "without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers." General Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana (1794-1876) The dominant figure in Mexican politics for much of the 19th century, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna left a legacy of disappointment and disaster by consistently placing his own self-interest above his duty to the nation. Born in the state of Vera Cruz in 1794, Santa Anna embarked on his long career in the army at age 16 as a cadet. He fought for a time for the Spanish against Mexican independence, but along with many other army officers switched sides in 1821 to help install Augustin de Iturbide as head of state of an independent Mexico. Mexico was a highly fractured and chaotic nation for much of its first century of independence, in no small part due to the machinations of men such as Santa Anna. In 1828 he used his military influence to lift the losing candidate into the presidency, being rewarded in turn with appointment as the highest-ranking general in the land. His reputation and influence were further strengthened by his critical role in defeating an 1829 Spanish effort to reconquer their former colony. In 1833 Santa Anna was overwhelmingly elected President of Mexico. Unfortunately, what began as a promise to unite the nation soon deteriorated into chaos. From 1833 to 1855 Mexico had no fewer than thirty-six changes in presidency; Santa Anna himself directly ruled eleven times. He soon became bored in his first presidency, leaving the real work to his vice-president, who soon launched an ambitious reform of church, state and army. In 1835, when the proposed reforms infuriated vested interests in the army and church, Santa Anna seized the opportunity to reassert his authority, and led a military coup against his own government. Santa Anna's repudiation of Mexico's 1824 constitution and substitution of a much more centralized and less democratic form of government was instrumental in sparking the Texas revolution, for it ultimately convinced both Anglo colonists and many Mexicans in Texas that they had nothing to gain by remaining under the Mexican government. When the revolution came in1835, Santa Anna personally led the Mexican counter-attack, enforcing a "take-no-prisoners" policy at the Alamo and ordering the execution of those captured at Goliad. In the end, however, his over-confidence and tactical carelessness allowed Sam Houston to win a crushing victory at the battle of San Jacinto. Although his failure to suppress the Texas revolution enormously discredited him, Santa Anna was able to reestablish much of his authority when he defeated a French invasion force at Vera Cruz in 1838. His personal heroism in battle, which resulted in having several horses shot out from under him and the loss of half of his left leg, became the basis of his subsequent effort to secure his power by creating a cult of personality around himself. In 1842 he arranged for an elaborate ceremony to dig up the remains of his leg, parade with it through Mexico City, and place it on a prominent monument for all to see. The United States took advantage of Mexico's continuing internal turmoil in the Mexican-American war. As the supreme commander of Mexican forces, much of the blame for their crushing defeat fell on Santa Anna's shoulders. Nevertheless, he remained the most powerful individual in Mexico until 1853, when his sale of millions of acres in what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico to the United States united liberal opposition against him. He was soon deposed, and never again returned to political office. He died in 1876. George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876) Flamboyant in life, George Armstrong Custer has remained one of the best-known figures in American history and popular mythology long after his death at the hands of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, and spent much of his childhood with a half-sister in Monroe, Michigan. Immediately after high school he enrolled in West Point, where he utterly failed to distinguish himself in any positive way. Several days after graduating last in his class, he failed in his duty as officer of the guard to stop a fight between two cadets. He was court-martialed and saved from punishment only by the huge need for officers with the outbreak of the Civil War. Custer did unexpectedly well in the Civil War. He fought in the First Battle of Bull Run, and served with panache and distinction in the Virginia and Gettysburg campaigns. Although his units suffered enormously high casualty rates -even by the standards of the bloody Civil War -- his fearless aggression in battle earned him the respect of his commanding generals and increasingly put him in the public eye. His cavalry units played a critical role in forcing the retreat of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's forces; in gratitude, General Philip Sheridan purchased and made a gift of the Appomatox surrender table to Custer and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer. In July of 1866 Custer was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Seventh Cavalry. The next year he led the cavalry in a muddled campaign against the Southern Cheyenne. In late 1867 Custer was court-martialed and suspended from duty for a year for being absent from duty during the campaign. Custer maintained that he was simply being made a scapegoat for a failed campaign, and his old friend General Phil Sheridan agreed, calling Custer back to duty in 1868. In the eyes of the army, Custer redeemed himself by his November 1868 attack on Black Kettle's band on the banks of the Washita River. Custer was sent to the Northern Plains in 1873, where he soon participated in a few small skirmishes with the Lakota in the Yellowstone area. The following year, he led a 1,200 person expedition to the Black Hills, whose possession the United States had guaranteed the Lakota just six years before. In 1876, Custer was scheduled to lead part of the anti-Lakota expedition, along with Generals John Gibbon and George Crook. He almost didn't make it, however, because his March testimony about Indian Service corruption so infuriated President Ulysses S. Grant that he relieved Custer of his command and replaced him with General Alfred Terry. Popular disgust, however, forced Grant to reverse his decision. Custer went West to meet his destiny. The original United States plan for defeating the Lakota called for the three forces under the command of Crook, Gibbon, and Custer to trap the bulk of the Lakota and Cheyenne population between them and deal them a crushing defeat. Custer, however, advanced much more quickly than he had been ordered to do, and neared what he thought was a large Indian village on the morning of June 25, 1876. Custer's rapid advance had put him far ahead of Gibbon's slower-moving infantry brigades, and unbeknownst to him, General Crook's forces had been turned back by Crazy Horse and his band at Rosebud Creek. On the verge of what seemed to him a certain and glorious victory for both the United States and himself, Custer ordered an immediate attack on the Indian village. Contemptuous of Indian military prowess, he split his forces into three parts to ensure that fewer Indians would escape. The attack was one of the greatest fiascos of the United States Army, as thousands of Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors forced Custer's unit back onto a long, dusty ridge parallel to the Little Bighorn, surrounded them, and killed all 210 of them. Countless paintings of "Custer's Last Stand" were made, including one mass-distributed by the Anheuser-Busch brewing company. Forgotten were the facts that he had started the battle by attacking the Indian village, and that most of the Indians present were forced to surrender within a year of their greatest battlefield triumph. Geronimo Warrior, Military Leader (1829-1909) A legend of the untamed American frontier, the Apache leader Geronimo was born in June 1829 in No-Doyohn Canyon, Mexico. He was a naturally gifted hunter, who, the story goes, as a boy swallowed the heart of his first kill in order to ensure a life of success on the chase. Being on the run certainly defined Geronimo's way of life. He belonged to the smallest band within the Chiricahua tribe, the Bedonkohe. Numbering a little more than 8,000, the Apaches were surrounded by enemies—not just Mexicans, but also other tribes, including the Navajo and Comanches. Raiding their neighbors was also a part of the Apache life. In response the Mexican government put a bounty on Apache scalps, offering as much as $25 for a child's scalp. But this did little to deter Geronimo and his people. At the age of 17 Geronimo had already led four successful raiding operations. Around this same time Geronimo fell in love with a woman named Alope. The two married and had three children together. Then tragedy struck. While out on a trading trip, Mexican soldiers attacked his camp. Word of the ransacking soon reached the Apache men. Quietly that night, Geronimo returned home, where he found his mother, wife and three children all dead. The murders devastated Geronimo. In the tradition of the Apache, he set fire to his family's belongings and then, in a show of grief, headed into the wilderness to bereave the deaths. There, it's said, alone and crying, a voice came to Geronimo that promised him: "No gun will ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans … and I will guide your arrows." Backed by this sudden knowledge of power, Geronimo rounded up a force of 200 men and hunted down the Mexican soldiers who killed his family. On it went for 10 years, as Geronimo exacted revenge against the Mexican government. In 1848, soon after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico ceded extensive lands in the Southwest to the United States, the Anglo-Americans made it clear they intended to restrict the old patterns of raiding and territorial use by the different Apache bands. The Anglo-American mines, ranches, and communities disrupted established Apache lifeways. The intruders set limits on where the Apaches could live and how. The Apaches, of course, had other ideas. Naturally, tensions mounted. The Apaches stepped up their attacks, which included brutal ambushes on stagecoaches and wagon trains. However, the Chiricahua leader, Geronimo's father-in-law, Cochise, could see where the future was headed. In an act that greatly disappointed his son-in-law, the revered chief called a halt to his decade-long war with the Americans and agreed to the establishment of a reservation for his people on a prized piece of Apache property. But within just a few years, Cochise died, and the federal government reneged on its agreement, moving the Chiricahua north so that settlers could move into their former lands. This act only further incensed Geronimo, setting off a new round of fighting. Geronimo proved to be as elusive as he was aggressive. However, authorities finally caught up with him in 1877 and sent him to the San Carlos Apache reservation. For four long years he struggled with his new reservation life, finally escaping in September 1881. Out on his own again, Geronimo and a small band of Chiricahua followers eluded American troops. Over the next five years they engaged in what proved to be the last of the Indian wars against the U.S. With his followers in tow, Geronimo shot across the Southwest. As he did, the seemingly mystical leader was transformed into a legend as newspapers closely followed the Army's pursuit of him. At one point nearly a quarter of the Army's forces—5,000 troops—were trying to hunt him down. Finally, in the summer of 1886, he surrendered, the last Chiricahua to do so. Over the next several years Geronimo and his people were bounced around, first to a prison in Florida, then a prison camp in Alabama, and then Fort Sill in Oklahoma. In total, the group spent 27 years as prisoners of war. James Knox Polk 11th President of the United States (1795-1849) James Polk was the 11th president of the United States, known for his territorial expansion of the nation chiefly through the Mexican-American War. James Knox Polk was born in Pineville, a small town in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on November 2, 1795, and graduated with honors in 1818 from the University of North Carolina. Leaving his law practice behind, he served in the Tennessee legislature, where he became friends with Andrew Jackson. Polk moved from the Tennessee legislature to the United States House of Representatives, serving from 1825 to 1839 (and serving as speaker of the House from 1835 to 1839). He left his congressional post to become governor of Tennessee. Leading into the presidential election of 1844, Polk was the frontrunner for the Democratic nomination for the vice presidency. Both would-be presidential candidates, Martin Van Buren for the Democrats and Henry Clay for the Whigs, sought to skirt the expansionist ("manifest destiny") issue during the campaign, seeing it as potentially controversial. The first step in distancing their campaigns was declaring opposition to the annexation of Texas. Polk, on the other hand, took a hard stance on the issue, insisting on the annexation of Texas and, in a roundabout way, Oregon. Enter Andrew Jackson, who knew that the American public favored westward expansion. He sought to run a candidate in the election committed to the precepts of manifest destiny, and at the Democratic Convention, Polk was nominated to run for the presidency. Polk went on to win the popular vote by a razor-thin margin, but took the Electoral College handily. James Polk took office on March 4, 1845—and, at 49 years of age, he became the youngest president in American history. Before Polk took the oath of office, Congress offered annexation to Texas, and when they accepted and became a new state, Mexico severed diplomatic relations with the United States and tensions between the two countries escalated. Regarding the Oregon territory, which was much larger than the current state of Oregon, President Polk would have to contend with England, who had jointly occupied the area for nearly 30 years. Polk's political allies claimed the entire Oregon area for the United States, from California northward to the 54° 40' latitude (the southern boundary of what is now Alaska), and so the mantra "54-40 or fight!" was born. Neither England nor the Polk administration wanted a war, and Polk knew that only war would likely allow the United States to claim the land. After back-and-forth negotiation, and some effective hard ball played by Polk, the British accepted the 49th parallel as the northern border (the current border between the United States and Canada), excluding the southern tip of Vancouver Island, and the deal was sealed in 1846. Things went less smoothly in the hunt for California and New Mexico, and ever-increasing tensions led to the Mexican-American War. After several battles and the American occupation of Mexico City, Mexico ceded New Mexico and California in 1848, and coast-to-coast expansion was complete. John J. Dunbar (Partially based on the real Reverend John Dunbar 1804-1857 in Nebraska-Kansas Pawnee territory) In 1863, First Lieutenant John J. Dunbar is wounded in the American Civil War. Choosing suicide over having his foot amputated, he takes a horse and rides up to and along the Confederate front lines, distracting them in the process. Despite numerous pot shots, the Confederates fail to shoot him off his mount. Whilst they are distracted, the Union army attacks the line, and the battle ends in a Confederate rout. Dunbar survives, and is allowed to recover properly, receives a citation for bravery, and is awarded Cisco, the horse who carried him, as well as his choice of posting. Dunbar requests a transfer to the western frontier so he can see it before it disappears. Dunbar is led to Fort Sedgwick, by Timmons, a Mule wagon provisionary. Dunbar finds the fort effectively abandoned and in need of repair. Despite the threat of nearby Indian tribes, he elects to stay and man the post himself. He begins rebuilding and restocking the fort and prefers the solitude afforded him, recording many of his observations in his diary. In the meantime, Timmons, the Mule wagon driver who transported Dunbar to Fort Sedgwick, is killed and scalped by Pawnee Indians on his way back to Fort Hays. Timmons' death and the suicide of Major Fambrough, who had sent them there, prevents other soldiers from knowing of Dunbar's assignment to the post, effectively isolating him. Dunbar notes in his diary how strange it is that no other soldiers join him at the post. Dunbar initially encounters his Sioux neighbors when several attempts are made to steal his horse and intimidate him. In response, Dunbar decides to seek out the Sioux camp in an attempt to establish a dialogue. On his way he comes across Stands with a Fist, who is attempting suicide in mourning her deceased husband. She is the white, adopted daughter of the tribe's medicine man Kicking Bird, her original family having been killed by the aggressive Pawnee tribe when she was young. Dunbar returns her to the Sioux to be treated, which changes their attitude toward him. Eventually, Dunbar establishes a rapport with Kicking Bird and warrior Wind in His Hair who equally wish to communicate. Initially the language barrier frustrates them, so Stands with a Fist, though with difficulty remembering her English, acts as translator. Dunbar finds himself drawn to the lifestyle and customs of the tribe and begins spending most of his time with them. Learning their language, he is accepted as an honored guest by the Sioux after he locates a migrating herd of buffalo and participates in the hunt. When at Fort Sedgwick, Dunbar also befriends a wolf he dubs "Two Socks" for its white forepaws. When the Sioux observe Dunbar and Two Socks chasing each other, they give him the name "Dances with Wolves". During this time, Dunbar also forges a romantic relationship with Stands with a Fist and helps defend the village from an attack by the rival Pawnee tribe. Dunbar eventually wins Kicking Bird's approval to marry Stands with a Fist, and abandons Fort Sedgwick. Because of the growing Pawnee and white threat, Chief Ten Bears decides to move the tribe to its winter camp. Dunbar decides to accompany them but must first retrieve his diary from Fort Sedgwick as he realizes that it would provide the army with the means of finding the tribe. However, when he arrives he finds the fort re-occupied by the U.S. Army. Because of his Sioux clothing, the soldiers open fire, killing Cisco and capturing Dunbar, arresting him as a traitor. Senior officers interrogate him, but Dunbar cannot prove his story, as a corporal has found and discarded his diary. Having refused to serve as an interpreter to the tribes, Dunbar is charged with desertion and transported back east as a prisoner. Soldiers of the escort shoot Two Socks when the wolf attempts to follow Dunbar, despite Dunbar's attempts to intervene. Eventually, the Sioux track the convoy, killing the soldiers and freeing Dunbar. At the winter camp, Dunbar decides to leave with Stands with a Fist, since his continuing presence will put the tribe in danger. As they leave, Wind In His Hair shouts to Dunbar, reminding him of their friendship. U.S. troops are seen searching the mountains but are unable to locate them, while a lone wolf howls in the distance. An epilogue states that thirteen years later the last remnants of the free Sioux were subjugated to the American government, ending the conquest of the Western frontier states and the livelihoods of the tribes on the plains. John Augustus Sutter (1803-1880) Sutter was born John Augustus Sutter in Baden, Germany, though his parents had originally come from Switzerland, a lineage of which he was especially proud. In 1834, faced with impossible debt, he decided to try his fortunes in America and, leaving his family in a brother's care, set sail for New York. There he decided that the West offered him the best opportunity for success, and he moved to Missouri, where for three years he operated as a trader on the Santa Fe Trail. By 1838, Sutter had determined that Mexican California held the promise of fulfilling his ambitious dreams, and he set off along the Oregon Trail, arriving at Fort Vancouver, near present-day Portland, Oregon, in hopes of finding a ship that would take him to San Francisco Bay. His journey involved detours to the Hawaiian Islands and to a Russian colony at Sitka, Alaska, but Sutter made the most of his wanderings by trading advantageously along the way. When he finally arrived in California in 1839, Sutter met first with the provincial governor in Monterey and secured permission to establish a settlement east of San Francisco (then called Yerba Buena) along the Sacramento River, in an area then occupied only by Indians. Sutter was granted nearly fifty thousand acres and authorized "to represent in the Establishment of New Helvetia [Sutter's Swiss-inspired name for his colony] all the laws of the country, to function as political authority and dispenser of justice, in order to prevent the robberies committed by adventurers from the United States, to stop the invasion of savage Indians and the hunting and trapping by companies from the Columbia." In other words, Sutter was to serve the California authorities as a bulwark against the assorted threats pressing in on them from Americancontrolled territories to the north and east. Ironically, as headquarters for his domain, Sutter chose a site on what he named the American River, at its junction with the Sacramento River and near the site of present-day Sacramento. Here, with the help of laborers he had brought with him from Hawaii, he built Sutter's Fort, a massive adobe structure with walls eighteen feet high and three feet thick. Two years later, in 1841, Sutter expanded his settlement when the Russians abandoned Fort Ross, their outpost north of San Francisco, and offered to sell it to him for thirty thousand dollars. Paying with a note he never honored, Sutter practically dismantled the fort and moved its equipment, livestock and buildings to the Sacramento Valley. Within just a few years, Sutter had achieved the grand-scale success he long dreamed of: acres of grain, a ten-acre orchard, a herd of thirteen thousand cattle, even two acres of Castile roses. His son came to share in his prosperity in 1844, and the rest of his family soon followed. At the same time, during these years Sutter's Fort became a regular stop for the increasing number of Americans venturing into California, several of whom Sutter employed. Besides providing him with a profitable source of trade, this steady flow of immigrants provided Sutter with a network of relationships that offered some political protection when the United States seized control of California in 1846, at the outbreak of the Mexican War. Barely a week before the war's end, however, there occurred a chance event that would destroy all John Sutter's achievements and yet at the same time link his name forever to one of the highpoints of American history. On the morning of January 24, 1848, a carpenter named James Marshall, who was building a sawmill for Sutter upstream on the American River near Coloma, looked into the mill's tailrace to check that it was clear of silt and debris and saw at the water's bottom nuggets of gold. Marshall took his discovery to Sutter, who consulted an encyclopedia to confirm it and then tried to pledge all his employees to secrecy. But within a few months, word had reached San Francisco and the gold rush was on. Suddenly all of Sutter's workmen abandoned him to seek their fortune in the gold fields. Squatters swarmed over his land, destroying crops and butchering his herds. "There is a saying that men will steal everything but a milestone and a millstone," Sutter later recalled; "They stole my millstones." By 1852, New Helvetia had been devastated and Sutter was bankrupt. He spent the rest of his life seeking compensation for his losses from the state and federal governments, and died disappointed on a trip to Washington, D.C. in 1880. José Antonio Carrillo (1796–1862) Captain José Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo (1796–1862) was a Californio rancher, officer, and politician in the early years of Mexican Alta California and U.S. California. He was the son of the Spanish Criollo José Raimundo Carrillo, and brother of Carlos Antonio Carrillo, governor of Alta California, himself serving three non-consecutive terms as Comandante of Pueblo de Los Angeles - Mayor of Los Angeles between 1826 and 1834. José Antonio Carillo married Estefana Pico (1806–) in 1823, and after her death, Jacinta Pico (1815–) in 1842; both women were sisters of prominent Californios Pío Pico and Andrés Pico. He built Carrillo House in Los Angeles, fronting the historic plaza, with wings extending back on Main Street. José Antonio Carrillo was the Mexican land grant grantee of Rancho Las Posas in 1834, in present day Ventura County, California, and the Island of Santa Rosa of the Channel Islands. Carrillo was alcalde of Los Angeles in 1826, 1828, and 1833. In 1836, Juan Bandini, a prominent political official who supported the American cause, was back in the revolution-making business - this time in opposition to Governor Juan Bautista Alvarado. Carrillo returned from his post as territorial congressman in Mexico with the news that his brother, Carlos, had been appointed governor of Alta California to replace Alvarado, and that the capital had been changed from Monterey to Los Angeles. During the Siege of Los Angeles, Carrillo, along with Captain José María Flores and Andrés Pico, formed a militia to defend Alta California during the Mexican–American War. Carrillo distinguished himself by leading fifty Californio Lancers to victory at the Battle of Dominguez Rancho against 203 United States Marines; killing 14, and wounding several others, while not suffering a single casualty. The Americans, under the command of US Navy Captain William Mervine, were forced to retreat from what is presently Carson to San Pedro Bay. Commodore Robert F. Stockton, leader of the US Pacific Naval Fleet, was so taken aback by the strong resistance of the Californios that he immediately set sail for San Diego to regroup. Two months later, Stockton rescued US Army General Stephen W. Kearny's surrounded forces after the Battle of San Pasqual, and with their combined, re-supplied force, they moved northward from San Diego, entering the Los Angeles area on January 8, 1847, linking up with John C. Frémont's Bear Flag battalion. With American forces totaling 660 soldiers and marines, they fought 150 Californios, led by José María Flores, with Carrillo second in command, in the Battle of Rio San Gabriel. The next day, January 9, 1847, they fought the Battle of La Mesa. On January 12, 1847, the last significant body of Californios surrendered to American forces. That marked the end of the war in California. On January 13, 1847, Carrillo, acting as a commissioner for Mexico, drafted in English and Spanish the Treaty of Cahuenga, and was present at the signing. He was a man of remarkable natural abilities for the most part unimproved and wasted. Slight modifications in the conditions and his character might have made him the foremost in Californians - either the best or the worst. None excelled him in intrigue, and he was never without a plot on hand. A gambler, of loose habits, and utterly careless in his associations, he yet never lost the privilege of associating with the best or the power of winning their friendship. There was nothing he would not do to oblige a friend or get the better of a foe; and there were few of any note who were not at one time or another both his foes and friends. No Californian could drink so much brandy as he with so little effect. A man of fine appearance and iron constitution; of generous impulses, without much principle; one of the few original and prominent characters in early California annals. Levi Strauss (1829-1902) Levi Strauss, the inventor of the quintessential American garment, was born in Buttenheim, Bavaria on February 26, 1829 to Hirsch Strauss and his second wife, Rebecca Haas Strauss; Levi had three older brothers and three older sisters. Two years after his father succumbed to tuberculosis in 1846, Levi and his sisters emigrated to New York, where they were met by his two older brothers who owned a NYC-based wholesale dry goods business called “J. Strauss Brother & Co.” Levi soon began to learn the trade himself. When news of the California Gold Rush made its way east, Levi journeyed to San Francisco in 1853 to make his fortune, though he wouldn’t make it panning gold. Strauss set up his own wholesale business, called simply Levi Strauss, and acted as the West Coast agent for his half-brothers. As his business grew, Strauss moved several times to larger quarters. Eventually David Stern joined his business. Their supplies came by ship, and the partners never knew what goods would be available. The items Strauss and Stern bought included denim work pants or the fabric itself. Most of their goods were sold to miners, but as more families came to San Francisco, Strauss and Stern added clothing for women and children. Strauss occasionally left the city to sell goods to the small shops opening up near mining camps. He developed a reputation for selling quality goods at a fair price. By 1861, Strauss had one of the most successful dry-goods businesses in San Francisco, and the firm continued to grow. Goods still came from the New York branch of the company, but Strauss also had items made on the West Coast, including pants. The first work pants he sold were made of canvas, but Strauss later switched to denim. He hired tailors to make the pants in their homes. The pants were just one of many products sold by Levi Strauss & Company. During these years, Strauss lived with Fanny and David Stern. Dressed formally for work, he walked each day to his office. At the company, however, Strauss was not formal with his workers, insisting they call him Levi. Strauss was also becoming a leader in San Francisco's Jewish community. He joined an organization that helped needy Jews in the region, and he helped raise money to build a temple and a cemetery. Around 1872, Levi received a letter from one of his customers, Jacob Davis, a Reno, Nevada tailor. In his letter, Davis disclosed the unique way he made pants for his customers, through the use of rivets at points of strain to make them last longer. Davis wanted to patent this new idea, but needed a business partner to get the idea off the ground. Levi was enthusiastic about the idea. The patent was granted to Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss & Company on May 20, 1873; and blue jeans were born. Levi carried on other business pursuits during his career, as well. He became a charter member and treasurer of the San Francisco Board of Trade in 1877. He was a director of the Nevada Bank, the Liverpool, London and Globe Insurance Company and the San Francisco Gas and Electric Company. In 1875, Levi and two associates purchased the Mission and Pacific Woolen Mills. He was also one of the city’s greatest philanthropists. Levi was a contributor to the Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum and Home, the Eureka Benevolent Society and the Hebrew Board of Relief. In 1897 Levi provided the funds for twenty-eight scholarships at the University of California, Berkeley, all of which are still in place today. At the end of the 19th century, Levi was still involved in the day-to-day workings of the company. In 1890 — the year that the XX waist overall was given the lot number “501®” — Levi and his nephews officially incorporated the company. Levi Strauss passed away on Friday, September 26th 1902. His estate amounted to nearly $6 million, the bulk of which was left to his four nephews and other family members, while donations were made to local funds and associations. President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the Waxhaws region on the border of North and South Carolina. The exact location of his birth is uncertain, and both states have claimed him as a native son; Jackson himself maintained he was from South Carolina. The son of Irish immigrants, Jackson received little formal schooling. The British invaded the Carolinas in 1780-1781, and Jackson’s mother and two brothers died during the conflict, leaving him with a lifelong hostility toward Great Britain. Jackson read law in his late teens and earned admission to the North Carolina bar in 1787. He soon moved west of the Appalachians to the region that would soon become the state of Tennessee, and began working as a prosecuting attorney in the settlement that became Nashville. He later set up his own private practice and met and married Rachel (Donelson) Robards, the daughter of a local colonel. Jackson grew prosperous enough to build a mansion, the Hermitage, near Nashville, and to buy slaves. In 1796, Jackson joined a convention charged with drafting the new Tennessee state constitution and became the first man to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee. Though he declined to seek reelection and returned home in March 1797, he was almost immediately elected to the U.S. Senate. Jackson resigned a year later and was elected judge of Tennessee’s superior court. He was later chosen to head the state militia, a position he held when war broke out with Great Britain in 1812. Andrew Jackson, who served as a major general in the War of 1812, commanded U.S. forces in a five-month campaign against the Creek Indians, allies of the British. After that campaign ended in a decisive American victory in the Battle of Tohopeka (or Horseshoe Bend) in Alabama in mid-1814, Jackson led American forces to victory over the British in the Battle of New Orleans (January 1815). The win, which occurred after the War of 1812 officially ended but before news of the Treaty of Ghent had reached Washington, elevated Jackson to the status of national war hero. In 1817, acting as commander of the army’s southern district, Jackson ordered an invasion of Florida. After his forces captured Spanish posts at St. Mark’s and Pensacola, he claimed the surrounding land for the United States. The Spanish government vehemently protested, and Jackson’s actions sparked a heated debate in Washington. Though many argued for Jackson’s censure, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams defended the general’s actions, and in the end they helped speed the American acquisition of Florida in 1821. Jackson won the presidential election of 1828 by a landslide, with John C. Calhoun as his vice-presidential running mate. Jackson's opponents nicknamed him "jackass," a moniker that Jackson took a liking to—so much that he decided to use the symbol of a donkey to represent himself. Though the use of that symbol died out, it would later become the emblem of the new Democratic Party. Jackson was the nation’s first frontier president, and his election marked a turning point in American politics, as the center of political power shifted from East to West. “Old Hickory” was an undoubtedly strong personality, and his supporters and opponents would shape themselves into two emerging political parties: The pro-Jacksonites became the Democrats (formally Democrat-Republicans) and the anti-Jacksonites (led by Clay and Daniel Webster) were known as the Whig Party. Jackson made it clear that he was the absolute ruler of his administration’s policy, and he did not defer to Congress or hesitate to use his presidential veto power. For their part, the Whigs claimed to be defending popular liberties against the autocratic Jackson, who was referred to in negative cartoons as “King Andrew.” Andrew Jackson took no action after Georgia claimed millions of acres of land that had been guaranteed to the Cherokee Indians under federal law, and he declined to enforce a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that Georgia had no authority over Native American tribal lands. In 1835, the Cherokees signed a treaty giving up their land in exchange for territory west of Arkansas, where in 1838 some 15,000 would head on foot along the so-called Trail of Tears. The relocation resulted in the deaths of thousands. Sitting Bull Tatanka-Iyotanka (1831-1890) A Hunkpapa Lakota chief and holy man under whom the Lakota tribes united in their struggle for survival on the northern plains, Sitting Bull remained defiant toward American military power and contemptuous of American promises to the end. Born around 1831 on the Grand River in present-day South Dakota, at a place the Lakota called "Many Caches" for the number of food storage pits they had dug there, Sitting Bull was given the name Tatanka-Iyotanka, which describes a buffalo bull sitting intractably on its haunches. It was a name he would live up to throughout his life. As a young man, Sitting Bull became a leader of the Strong Heart warrior society and, later, a distinguished member of the Silent Eaters, a group concerned with tribal welfare. He first went to battle at age 14, in a raid on the Crow, and saw his first encounter with American soldiers in June 1863, when the army mounted a broad campaign in retaliation for the Santee Rebellion in Minnesota, in which Sitting Bull's people played no part. The next year Sitting Bull fought U.S. troops again, at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain, and in 1865 he led a siege against the newly established Fort Rice in present-day North Dakota. Widely respected for his bravery and insight, he became head chief of the Lakota nation about 1868. The stage was set for war between Sitting Bull and the U.S. Army in 1874, when an expedition led by General George Armstrong Custer confirmed that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory, an area sacred to many tribes and placed off-limits to white settlement by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Despite this ban, prospectors began a rush to the Black Hills, provoking the Lakota to defend their land. When government efforts to purchase the Black Hills failed, the Fort Laramie Treaty was set aside and the commissioner of Indian Affairs decreed that all Lakota not settled on reservations by January 31, 1876, would be considered hostile. Sitting Bull and his people held their ground. Inspired by a vision, the Oglala Lakota war chief, Crazy Horse, set out for battle with a band of 500 warriors, and on June 17 he surprised Crook's troops and forced them to retreat at the Battle of the Rosebud. To celebrate this victory, the Lakota moved their camp to the valley of the Little Bighorn River, where they were joined by 3,000 more Indians who had left the reservations to follow Sitting Bull. Here they were attacked on June 25 by the Seventh Cavalry under George Armstrong Custer, whose badly outnumbered troops first rushed the encampment, as if in fulfillment of Sitting Bull's vision, and then made a stand on a nearby ridge, where they were destroyed. In May 1877 he led his band across the border into Canada, beyond the reach of the U.S. Army, and when General Terry traveled north to offer him a pardon in exchange for settling on a reservation, Sitting Bull angrily sent him away. Four years later, however, finding it impossible to feed his people in a world where the buffalo was almost extinct, Sitting Bull finally came south to surrender. On July 19, 1881, he had his young son hand his rifle to the commanding officer of Fort Buford in Montana, explaining that in this way he hoped to teach the boy "that he has become a friend of the Americans." Yet at the same time, Sitting Bull said, "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle." He asked for the right to cross back and forth into Canada whenever he wished, and for a reservation of his own on the Little Missouri River near the Black Hills. Instead he was sent to Standing Rock Reservation, and when his reception there raised fears that he might inspire a fresh uprising, sent further down the Missouri River to Fort Randall, where he and his followers were held for nearly two years as prisoners of war. In the fall of 1890, a Miniconjou Lakota named Kicking Bear came to Sitting Bull with news of the Ghost Dance, a ceremony that promised to rid the land of white people and restore the Indians' way of life. Lakota had already adopted the ceremony at the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations, and Indian agents there had already called for troops to bring the growing movement under control. At Standing Rock, the authorities feared that Sitting Bull, still revered as a spiritual leader, would join the Ghost Dancers as well, and they sent 43 Lakota policemen to bring him in. Before dawn on December 15, 1890, the policemen burst into Sitting Bull's cabin and dragged him outside, where his followers were gathering to protect him. In the gunfight that followed, one of the Lakota policemen put a bullet through Sitting Bull's head. Sitting Bull was buried at Fort Yates in North Dakota, and in 1953 his remains were moved to Mobridge, South Dakota, where a granite shaft marks his grave. The Bidwells John Bidwell 1819-1900 Annie Bidwell 1839-1918 Bidwell was born in Chautauqua County, New York. The Bidwell family was originally from England and came to America in the colonial era. The Bidwell family moved to Erie, Pennsylvania in 1829, and then to Ashtabula County, Ohio in 1831. At age 17, he attended and shortly thereafter became Principal of Kingsville Academy. In 1841 Bidwell became one of the first emigrants on the California Trail. John Sutter employed Bidwell as his business manager shortly after Bidwell's arrival in California. Shortly after the James W. Marshall's discovery at Sutter's Mill, Bidwell also discovered gold on the Feather River establishing a productive claim at Bidwell Bar in advance of the California Gold Rush. Bidwell obtained the four square league Rancho Los Ulpinos land grant after being naturalized as a Mexican citizen in 1844, and the two square league Rancho Colus grant on the Sacramento River in 1845; later selling that grant and buying Rancho Arroyo Chico on Chico Creek to establish a ranch and farm. Bidwell obtained the rank of chief while fighting in the Mexican–American War. He served in the California Senate in 1849, supervised the census of California in 1850 and again in 1860. He was a delegate to the 1860 national convention of the Democratic Party. He was appointed brigadier general of the California Militia in 1863. He was a delegate to the national convention of the Republican Party in 1864 and was a Republican member of Congress from 1865 to 1867. In 1865, General Bidwell backed a petition from settlers at Red Bluff, California to protect Red Bluff's trail to the Owhyhee Mines of Idaho. The United States Army commissioned 7 forts for this purpose, and selected a site near Fandango Pass at the base of the Warner Mountains in the north end of Surprise Valley, and on June 10, 1865 ordered Fort Bidwell to be built there. The fort was built amid escalating fighting with the Snake Indians of eastern Oregon and southern Idaho. It was a base for operations in the Snake War that lasted until 1868 and the later Modoc War. Although traffic dwindled on the Red Bluff route once the Central Pacific Railroad extended into Nevada in 1868, the Army staffed Fort Bidwell to quell various uprisings and disturbances until 1890. A Paiute reservation and small community maintain the name Fort Bidwell. His wife, Annie Kennedy Bidwell, was the daughter of Joseph C. G. Kennedy, a socially prominent, high ranking Washington official in the United States Census Bureau who was active in the Whig party. She was deeply religious, and committed to a number of moral and social causes. Annie was very active in the suffrage and prohibition movements. Annie was concerned for the future of the local Mechoopda Native Americans during the life of her husband, and was active in state and national Indian associations. The Bidwells were married April 16, 1868 in Washington, D.C. with then President Andrew Johnson and future President Ulysses S. Grant among the guests. Upon arrival in Chico, the Bidwells used their mansion extensively for entertainment of friends. Some of the guests who visited Bidwell Mansion were President Rutherford B. Hayes, General William T. Sherman, Susan B. Anthony, Frances Willard, Governor Leland Stanford, John Muir, Joseph Dalton Hooker and Asa Gray. In 1875 Bidwell ran for Governor of California on the Anti-Monopoly Party ticket. As a strong advocate of the temperance movement, he presided over the Prohibition Party state convention in 1888 and was the Prohibition candidate for governor in 1880. In 1892, Bidwell was the Prohibition Party candidate for President of the United States. The Bidwell/Cranfill ticket came in fourth place and received 271,058 votes, or 2.3% nationwide. It was the largest total vote and highest percentage of the vote received by any Prohibition Party national ticket. Narcissa Whitman (1808-1847) Among the first American settlers in the West, the Whitmans played an important role in opening the Oregon Trail and left a tragic legacy that would continue to haunt relations between whites and Indians for decades after their deaths. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were both from upstate New York. Narcissa Prentiss was born in 1808 in Prattsburgh, New York, into a devout Presbyterian family. She was fervently religious as a child, at age sixteen pledging her life to missionary work. After she completed her own education, she taught primary school in Prattsburgh. In 1834, still awaiting the opportunity to fulfill her pledge, she moved with her family to Belmont, New York. Marcus Whitman was born in 1802 at Rushville, New York. After studying under a local doctor, he received his degree from the medical college at Fairfield, New York, in 1832. He practiced medicine for four years in Canada, then returned to New York, where he became an elder of the Presbyterian Church. In 1835 he journeyed to Oregon to make a reconnaissance of potential mission sites. In 1836 the Whitmans headed West with another missionary couple, Henry Harmon Spalding (who had been jilted by Narcissa) and his wife Eliza, and with a prospective missionary named William H. Gray. St. Louis was their departure point and Oregon their ultimate destination. The group travelled with fur traders for most of the journey, and took wagons farther West than had any American expedition before them. Along the way, Narcissa and Eliza became the first white women to cross the Rocky Mountains. The Whitmans reached the Walla Walla River on September 1, 1836, and decided to found a mission to the Cayuse Indians at Waiilatpu in the Walla Walla Valley. The Spaldings travelled on to present-day Idaho where they founded a mission to the Nez Perce at Lapwai. The Whitmans labored mightily to make their mission a success. Marcus held church services, practiced medicine and constructed numerous buildings; Narcissa ran their household, assisted in the religious ceremonies, and taught in the mission school. At first the couple was optimistic and seemed almost thrilled by the challenges their new life posed; Narcissa wrote home, "We never had greater encouragement about the Indians than at the present time." This optimism soon faded, however. The Whitman's two-year-old daughter drowned in 1839, Narcissa's eyesight gradually failed almost to the point of blindness, and their isolation dragged on year after year. Above all, the Cayuse continued to be unreceptive to their preaching of the gospel. To the Cayuse, whose souls the Whitmans felt they were destined to "save," the mission was at first a strange sight, and soon a threatening one. The Whitmans made little effort to offer their religious message in terms familiar to the Cayuse, or to accommodate themselves even partially to Cayuse religious practices. Gift-giving was essential to Cayuse social and political life, yet the Whitmans saw the practice as a form of extortion. For the Cayuse, religion and domestic life were closely entwined, yet Narcissa reacted with scorn when they suggested a worship service within the Whitman household. Even a sympathetic biographer admits that "her attitude toward those among whom she lived came to verge on outright repugnance." These close connections between the Whitmans' mission and white colonization further alienated the Cayuse. The swelling number of whites coming into Oregon brought with them numerous diseases which ravaged the Cayuse, and the Whitmans' aid to the wagon trains made the Cayuse especially suspicious of them. Even Narcissa observed this, noting in July 1847 that "the poor Indians are amazed at the overwhelming numbers of Americans coming into the country... They seem not to know what to make of it." The Indians' suspicions gave way to rage in late 1847, when an epidemic of measles struck nearby whites and Cayuse alike. Although the Whitmans ministered to both, most of the white children lived while about half of the Cayuse, including nearly all their children, died. On November 29, 1847, several Cayuse, under the leadership of the chief Tiloukaikt, took revenge for what they perceived as treachery. They killed fourteen whites, including the Whitmans, and burnt down the mission buildings.