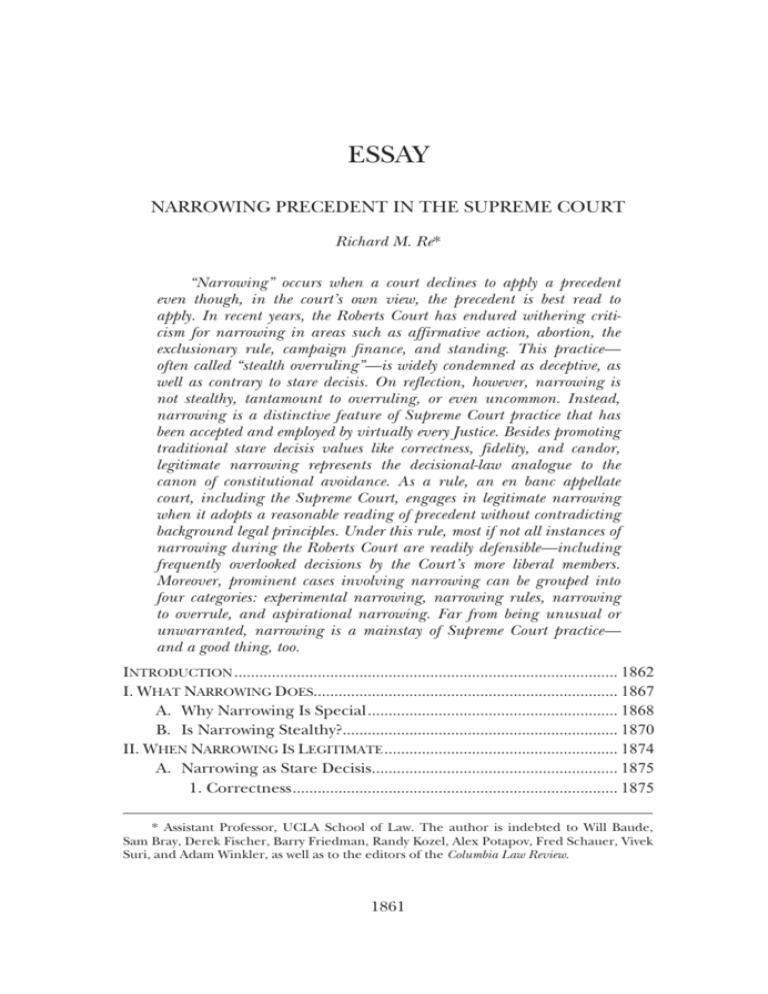

narrowing precedent in the supreme court

advertisement