Improving Medication Safety in Community Pharmacy: Assessing

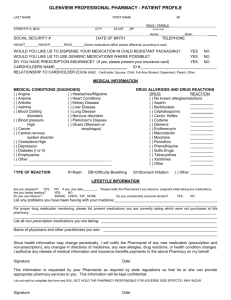

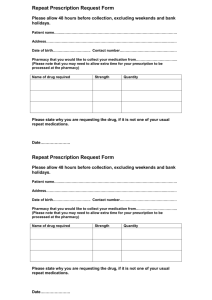

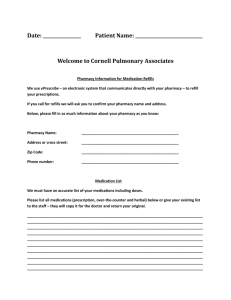

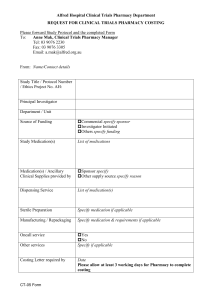

advertisement