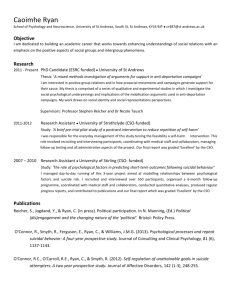

On Psychological Growth and Vulnerability: Basic Psychological

advertisement