ARTICLE IN PRESS

Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

www.elsevier.com/locate/appet

Research report

Is the desire to eat familiar and unfamiliar meat products influenced by

the emotions expressed on eaters’ faces?

S. Rousseta,!, P. Schlichb, A. Chatonniera, L. Barthomeufc, S. Droit-Voletc

a

Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, UMR 1019, Centre de Recherche en Nutrition Humaine d’Auvergne, 58 rue Montalembert,

63009 Clermont-Ferrand, France

b

Centre Européen des Sciences du Goût, 15 rue Hugues Picardet, 21000 Dijon, France

c

Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive, UMR 6024 CNRS, 34 Avenue Carnot, 63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France

Received 12 October 2006; received in revised form 1 June 2007; accepted 1 June 2007

Abstract

The aim of the present study was to test if the social context represented by eaters’ faces expressing emotions can modulate the desire to

eat meat, especially for unfamiliar meat products. Forty-four young men and women were presented with two series of photographs. The

first series (non-social context) was composed of eight meat pictures, four unfamiliar and four familiar. The second series (social context)

consisted of the same pictures presented with eaters expressing three different emotions: disgust, pleasure or neutrality. For every picture,

the participants were asked to estimate the intensity of their desire to eat the meat product viewed on the picture. Results showed that

meat desire depended on interactions between product familiarity, social context and the participant’s gender. In the non-social context,

the men liked the familiar meat products more than the women, whereas their desire to eat unfamiliar meat products was similar.

Compared to the non-social context, viewing another person eating with a neutral and a happy facial expression increased the desire to

eat. Furthermore, the increase in the desire to eat meat associated with happy faces was greater for the unfamiliar than for the familiar

meat products in men, and greater for the familiar than for the unfamiliar meats in women. In the presence of disgusted faces, the desire

to eat meat remained constant for unfamiliar products in all participants whereas it only decreased for familiar products in men.

r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Eating; Emotion; Meat; Faces; Familiarity

Introduction

The sensory aspects of foods elicit emotional reactions of

pleasure or disgust that are often considered as major

reasons for the choice and the preference of foods

(Eertmans, Baeyens, & Van den Bergh, 2001; Meiselman

& Rivlin, 1986; Rozin, 1990). Dislike of a food thus leads

to its rejection. However, according to Rozin and Fallon

(1980), three psychologically meaningful categories explain

food rejection: distaste, danger and disgust. Distaste is

produced by the dislike of the appearance, taste or smell

and/or texture of food. Danger is associated with the

harmful consequences of ingestion. Disgust is generated on

!Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: rousset@clermont.inra.fr (S. Rousset),

droit-volet@univ-bpclermont.fr (S. Droit-Volet).

0195-6663/$ - see front matter r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.appet.2007.06.005

both ideational grounds and the distaste produced by

contamination or by the intake of inedible foodstuffs.

Food avoidance, a related but different topic concerns

the process of rejection of unfamiliar food. This is related

to neophobia, the reluctance to try unfamiliar foods, and

the willingness to taste familiar rather than unfamiliar

foods (Pliner & Hobden, 1992; Pliner, Latheenmaki, &

Tuorila, 1998). Among the causes of neophobia are the fear

of experiencing a bad taste and/or of being poisoned, as

well as the fear of new experiences, more closely related to

personality traits. Regardless of the case, reactions to

unfamiliar animal foods, particularly meats, would also be

mediated by the strong basic emotion of disgust (Pliner &

Pelchat, 1991). To decrease neophobia, the authors

proposed either to force exposure to an unfamiliar food

in order to confirm or not the expectation of unpalatability

(Pliner, 1982; Pliner & Hobden, 1992; Zajonc, 1968;

ARTICLE IN PRESS

2

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

Zajonc, Markus, & Wilson, 1974), to associate this food

with pleasant or familiar tastes by conditioning, or to

provide information about these foods (Martins, Pelchat,

& Pliner, 1997). To date, however, the possibility of

decreasing or increasing neophobia in the social context by

the presence of another person or other people expressing

different emotions towards the unfamiliar food products

has been rarely empirically studied.

Since Lewin (1958), study in the power of the social

context has been demonstrated on the change in eating

habits, notably concerning disliked foods such as beef

heart, sweetbread and kidneys. This author tested the

influence of two types of intervention (individual and

group) on housewives. In the individual case, only 3% of

the women as opposed to 32% in the group case actually

tried these meats. Although several factors explained these

results, Lewin emphasized the influence of the social group

and the difficulties of individuals to differentiate themselves

too much from the group. As he said, the individual is

likely to change only if the group changes (Lewin &

Grabbe, 1945).

The effect of social influence in the domain of eating is

now well known (for a review see Herman, Roth, and

Polivy (2003)). Notably, modelling studies suggested that

the presence of others may facilitate or inhibit intake,

depending on how much the model(s) eat(s). For example,

Rosenthal and McSweeney (1979) showed that when a

model ate either 40 or 10 crackers, participants ate more

when paired with a high-consumption confederate than

when paired with a low consumption confederate. The

presence of others influences not only the amount of food

eaten, but also the choice of the consumed food, as

shown by Birch (1980). In her experiment, a ‘target’

child preferred vegetables A to B, while all of the other

children at the same table preferred vegetables B. During

four successive meals, the two vegetables were offered.

When the target child serves himself first, he generally

chooses vegetable A (in 80% of the cases). On the

other hand, when he serves himself last, he tends to imitate

the others and chooses vegetable B in 67% of the cases.

Birch did not draw any conclusions from the respective

effects of simple exposure to the vegetables, the emotional

context of the meal or the mimicking of behaviour. As

regards the impact of modelling on willingness to eat novel

foods, Harper and Sanders (1975) showed that more

children were willing to taste a novel food if the adult

model tasted it first than if it was only offered. Moreover,

when adult participants were exposed to eater models who

ostensibly chose novel foods among familiar and unfamiliar foods, participants were more often inclined to choose

novel foods than when they viewed models choose familiar

foods (Hobden & Pliner, 1995). In their works, Birch

(1980), and Harper and Sanders (1975) did not control the

influence of emotions expressed by the children’s or adults’

faces on the target child’s willingness to taste the vegetables

or the novel food. Conversely, Hobden and Pliner (1995)

obtained their results while showing models who expressed

neutral faces during the choice and tasting of food

products.

In non-specific nutrition-related domains of research, it

is well known that the perception of emotions expressed by

faces plays an important role on our own emotions

(Adolphs, Damasio, Tranel, Cooper, & Damasio, 2000;

Decety & Chaminade, 2003; Gallese, 2003). Indeed,

‘emotional contagion’ results from conscious appraisal,

but also from more automatic mechanisms inaccessible to

awareness, such as the automatic imitation of facial

expressions in others (Hatfield, Cacioppo, & Rapson,

1994). The recent embodiment theories of cognition hold

that the encoding of incoming emotional information

involves an internal simulation of the perceived entities

(e.g., imitation of the facial expression) with all of its

physiological implications such as matching of emotional

state (see Barsalou, Nidenthal, Barbey, & Ruppert, 2003;

Niedenthal, Barsalou, Winkielman, Krauth-Gruber, & Ric,

2005, for a review). For example, in an fMRI study,

Phillips et al. (1998) showed that the perception of facial

expression of disgust produced activation of the anterior

insula, directly involved in the physiological reaction of

disgust. In the same way, Adolphs, Tranel, and Damasio

(2003) reported on patients with damage affecting the

insula who clearly showed selective impairment in recognising facial expressions of disgust and in their sensitivity

to disgust. Since the discovery of the mirror-neuron system

(Gallese, 2005), there is now evidence that observing or just

imagining a person in a particular emotional state

automatically arouses this state with all of the somatic

and associated sensory-motor responses (Craig, 2002;

Rizzolati, Fadiga, Fogassi, & Gallese, 2002; Singer et al.

2004).

In short, the different studies described above suggest the

important power of social context on the amount of food

eaten and on the evaluation of liking or disliking food

products, especially in the case of rejection of unfamiliar

food and, more particularly, unfamiliar meat. The aim of

the present study was thus to investigate the possibility of

changing the participants’ desire to eat a food product by

the presence of other people expressing and arousing

different specified emotions. More precisely, we tested how

emotional facial expressions (pleasure, neutrality and

disgust) affect the participants’ desire to eat four familiar

and four unfamiliar meat products. We expected that

eaters’ faces expressing pleasure would increase the desire

to eat meat, compared to those expressing neutrality and

disgust, and inversely for the faces expressing disgust.

Considering the rejection of novel food, we hypothesized

that the participants should have less desire to eat

unfamiliar than familiar products. Furthermore it might

be possible that the change in desire to eat would be greater

for unfamiliar than for familiar meat products because

participants did not have any previous sensory experience

with these new foods that would influence the importance

of emotional context in the changes in neophobia. Finally

due to an in-group advantage (Durrett & Levin, 2005), i.e.,

ARTICLE IN PRESS

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

the tendency to imitate more members of our own group,

we also assumed that the gender of the eaters might

influence the responses of the participants.

Method

Participants

In December 2004, a convenience sample was recruited

in Clermont-Ferrand (France) through advertising in the

local newspapers, TV and displays in stores (supermarkets). Among the subjects who phoned, 95% agreed to

participate in the experiment. Eighty-eight young people,

44 men and 44 women, were recruited outside of our

laboratory, with a mean age of 24.5 (SD 2.9). The mean

body mass index (BMI) for men and women was 22.5 (SD

2.9) and 20.1 (SD 2.4), respectively. Participants were not

receiving medical treatment for any progressive illness.

They received a payment of h20 as compensation.

Materials and their validation

Pictures

The stimulus set consisted of eight pictures of meat

products and 18 of the emotional facial expressions of

models (three men and three women expressing pleasure,

neutrality and disgust). All the pictures were taken with a

digital camera (Canon Power Shot G3, 4.0 Mega pixels,

objective lens 7.2–28.8 mm 1:2.0–3.0) with a high-angle

shot in order to show large objects in detail. These

photographs were selected from a larger set of photographs

on the basis of two pre-tests, one for the meat products and

the other for the emotional expressions of the models. For

each pre-test, additional participants were recruited as

explained below.

Pre-test of pictures of meat products

Two categories of meat products were tested: unfamiliar

versus familiar meat products. Four unfamiliar beef

products were prepared by a technical centre (Association

de Développement de l’Institut de la Viande): ‘dry ham’,

3

‘cooked sausage with vegetables’, ‘cooked sausage with 5%

fat’, and another ‘cooked sausage with 15% fat’. Four

familiar pork products were purchased in a supermarket.

They were bacon, dry sausage, cooked sausage and

pistachio galantine. These food products were displayed

on a simple white plate placed on a table covered with a

beige tablecloth (Fig. 1). These eight photographs had been

previously assessed by 24 participants with a mean age of

26 (SD ¼ 4, 13 women and 11 men). Each participant rated

each photograph on perceived familiarity and classified

meat products into one of the three meat types (fresh meat,

processed pork and offal). Familiarity was assessed on a

seven-point scale (from 0, ‘‘not familiar at all’’, to 6,

‘‘extremely familiar’’). The ANOVA (effect of products

nested according to the category: unfamiliar vs. familiar

products on the ratings of familiarity) shows that the

familiarity scores of the four familiar meat products were

higher than those of unfamiliar meat products: 4.3 vs. 2.1,

p ¼ 0.03. Moreover, the familiar and unfamiliar meat

products were classified by 93% and 75% of participants as

processed meat, respectively.

Pre-test of pictures of facial expressions

Ten models, five men (mean age: 24) and five women

(mean age: 25) with a standard body mass index between

19 and 25 were recruited for the photographs. Sixty

photographs of these ten subjects showing three different

emotional expressions—neutrality, disgust and pleasure—

were taken twice under standard conditions (Fig. 2). These

photographs were then evaluated by 21 additional participants (ten men and 11 women, mean age: 25 (SD ¼ 3).

Photographs were presented in random order to the

participants. They rated each face on the basis of nine

emotional expressions: anger, disgust, fear, sadness, guilt,

surprise, interest, satisfaction and pleasure (Ekman,

Levenson, & Friesen, 1983). The term ‘without emotion’

was also added to the nine emotional expressions to

illustrate neutrality. For each emotion, the participants

responded on a seven-point scale (0, ‘‘the face does not

express this emotion’’, to 6, ‘‘the face strongly expresses

this emotion’’).

Fig. 1. Examples of familiar and unfamiliar meat products.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

4

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

Fig. 2. Examples of faces expressing pleasure, neutrality and disgust used for the validation of expression.

3

M2D1W2D1

M4D1M2D2

W5D1

M4D2

M3D1W3D2

W2D2

M3D2W3D1

W4D2

W1D2M1D2

W1D1

M1D1

2

DIM2 28.76 %

1

disgust

W5D2

W4D1

M5D1

0

-1

W4P2

W3P1

W1P1 W2P2

M3P1

M3P2

W5P1M1P1W2P1

M5P1M4P1

M2P1W3P2M1P2

pleasure M2P2M4P2

W4P1

anger

surprise

fear

guilty

sad

W1P2 satisfaction

M5P2

interest

W5P2

M5D2

M3N1

W1N2

-2

M2N2

M2N1

W5N2 W4N2

M3N2 W3N1

M4N2

M1N2

neutrality

M1N1 W4N1

W3N2 M4N1

W5N1 W1N1

W2N2

W2N1

M5N1

M5N2

-3

-4

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

DIM1 65.10%

Covariance Biplot-PCs and Loadings*4

Fig. 3. Location of the ten preliminary eater models with the three facial expressions in the emotional space (principal plot of PCA). The first two

characters indicate the gender (M: man and W: for woman) and the model code (no. 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5). The third character, D, N and P, indicates that the

model expresses disgust, neutrality or pleasure. The last number shows the photograph replicate.

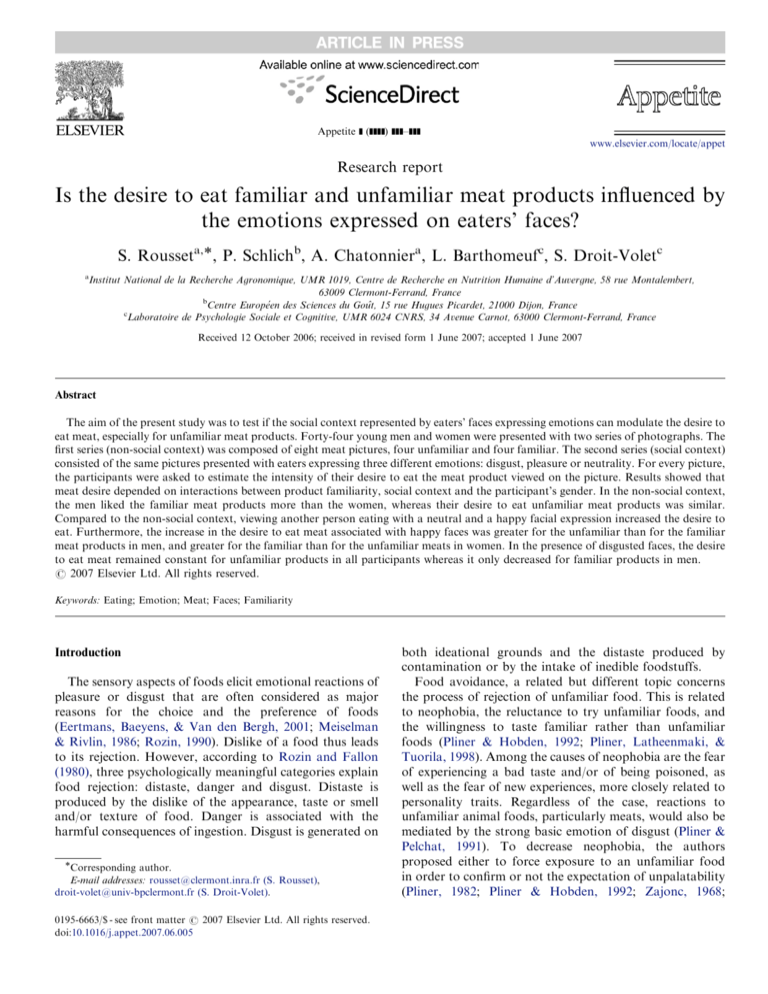

A principal component analysis (PCA) computed on the

covariance matrix was carried out with the mean intensities

of emotional words for each photograph. The first two axes

of the PCA accounted for 94% of total inertia, i.e., the

information generated by all of the data (Fig. 3). The right

part of the first horizontal axis was explained by ‘‘satisfaction’’, ‘‘pleasure’’ and ‘‘interest’’, which were opposed to

‘‘fear’’, ‘‘sadness’’ and ‘‘guilt’’ (the left part of the first

axis). The second vertical axis opposed ‘‘disgust’’ and

‘‘anger’’ at the top, to ‘‘neutrality’’ at the bottom.

‘‘Surprise’’ was poorly represented on the plot. In that

emotional space, three distinct groups of faces appeared.

The faces expressing pleasure were located on the right,

those expressing neutrality at the bottom, and those

showing disgust in the top left corner. This result clearly

showed that the participants easily identified the three

types of emotions mimicked by the models. Certain

emotional face pictures (W1P2, M5P2, W5P2, W1N2,

M5D2, M3N1, W5D2, W4D1, M5D1, W1D1 and M1D1)

located between the groups were less clearly identified. The

results of the analyses of variance (eater’s face nested

according to gender) for each emotion confirmed that there

were significant differences in pleasure and disgust scores

given to the 20 faces expressing pleasure and disgust, F(18,

400) ¼ 5.1, po0.0001 and F(18, 400) ¼ 20.4, po0.0001 for

pleasure and disgust, respectively. However, there was little

difference in the 20 neutral scores distinguishing neutral

faces, F(18, 400) ¼ 1.5, p ¼ 0.09. The gender of the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

photographed eater did not have a significant effect on the

evaluation of disgust, F(1, 18) ¼ 0.02, p ¼ 0.89, pleasure

F(1, 18) ¼ 0.97, p ¼ 0.34 or neutral expression, F(1,

18) ¼ 0.13, p ¼ 0.72.

Table 1 shows the scores of the faces that best expressed

disgust, neutrality and pleasure, and that did not differ

between themselves in each emotional category. We therefore eliminated M5 because of its lower score of expressiveness of disgust (2.1), W4 because its disgust score was

slightly lower than those of the other subjects (4.3), and M3

and W5 because their pleasure scores (3.9 and 4.5) were

lower than those of the others.

After the six eaters were selected on the basis of their

validated emotional expressions (Fig. 2), photographs of

their body seated at a table in front of a plate containing

one of the eight meat contents were taken and subsequently

attached to their heads using Photoshop (Fig. 4).

Table 1

Intensity of emotions perceived from the six eaters that best expressed

disgust, neutrality and pleasure

Emotional expressions

Pleasure

Neutrality

Disgust

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Mean

SD

Selected eater

Mena

M1

M2

M4

5.1

4.1

4.3

1.6

1.7

1.6

3.7

3.0

3.6

1.7

1.9

2.0

4.7

5.4

5.2

1.1

1.0

1.0

Womena

W1

W2

W3

4.9

5.3

5.3

1.5

1.3

1.0

3.8

3.8

3.7

2.1

2.2

2.1

5.1

5.3

4.9

1.4

0.8

1.1

a

The first two characters indicate the sex (M for men and W for women)

and the code (no. 1, 2, 3 or 4) of the selected eater.

5

Procedure

Subjects other than those used in the pre-tests participated in one session at the laboratory, each between 11:00

am and 2:00 pm or between 6:00 pm and 8:00 pm. They

were only instructed that they had to watch meat pictures

and to assess their desire to eat the products shown on the

picture. Each participant was presented with two series of

pictures on a computer, the order of the series being

counterbalanced across subjects. The first series was

composed of the eight meat products (four familiar and

four unfamiliar). The second series included 48 pictures,

i.e., two eaters (one man and one women chosen from

among the six selected eaters and not always the same,

depending on the participants) for the three emotional

expressions (disgust, neutrality and pleasure), and this for

the eight meat products. Within each series, pictures were

presented in random order. For each picture, the participants assessed the intensity of their eating desire on a

vertical and non-structured scale (from the bottom, ‘‘I have

no desire to eat’’, to the top ‘‘I have a great desire to eat’’).

Scores varied between 0 and 10. Both the pictures and the

eating desire scale were presented on the same screen. After

the participant scored his/her evaluation, the next screen

appeared.

Statistical analyses

We used three models of analysis of variance (repeated

measurements GLM procedure of SAS), considering the

successive evaluations of meat pictures by a given subject

as repeated measurements. The first one was performed on

the data of the first series of pictures (meat products in a

non-social context). It was a 2*2 ANOVA run on the

eating desire scale value (from 0 to 10) with participant’s

gender as a between-subject factor, familiarity (familiar vs.

unfamiliar) as a within-subject factor, and with their

interaction. The four different meat products were

Fig. 4. Examples of a male model with expressions of pleasure, neutrality and disgust towards bacon.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

considered as replicates within each familiarity level. The

following three analyses (2*2*2 ANOVAs) were carried out

on the data with the same two factors (participant’s gender,

familiarity), and an additional within-subject factor, i.e.,

the two-picture series: meat presented in the non-social and

a one-out-of-three social context (neutral, pleasure or

disgust expressions). This was done in order to test the

effect of facial expressions in each emotional condition. In

this analysis, the scores given to the pictures showing male

and female eater models were averaged. In order to better

understand interactions, we used other ANOVA models.

For example, we performed an ANOVA with context and

familiarity as within-subject factors and gender as a

between-subjects factor, for each type of product (familiar

vs. unfamiliar). Moreover, for each gender and level of

familiarity, we carried out a repeated measures one-way

ANOVA to determine the effect of context. The last fourway ANOVA (3*2*2*2) aimed to compare the three

emotional facial expressions and assessed the impact of

eater model and participant’s gender on meat eating desire,

as well as product familiarity and their interactions.

Results

Influence of participant’s gender and product familiarity on

the desire to eat meat in a non-social context

The repeated measures analysis of variance showed two

main effects: product familiarity, F(1, 86) ¼ 91.2, po0.

0001, indicating that the familiar products elicited more

desire to eat than the unfamiliar products (the first two

bars in Fig. 5a and b). However, there was also a main

effect of the participant’s gender, F(1, 86) ¼ 3.8, po0.05,

as well as a significant familiarity " gender interaction, F(1,

86) ¼ 4.0, po0.05. This interaction indicated that the

gender difference in the desire to eat meat products was

greater for the familiar meat products, F(1, 86) ¼ 6.0,

po0.01, than for the unfamiliar products, F(1, 86) ¼ 0.9,

po0.4 (Fig. 5a and b). Thus, men wanted to eat meat

products more than women, but only in the case of familiar

foods.

Comparison of the non-social and social context on the desire

to eat meat

Non-social vs. social contexts: neutral faces

Repeated measures analysis of variance showed two

marginally significant effects of the participant’s gender

and of the context without significant interaction between

these two factors, F(1, 86) ¼ 3.6, po0.06, F(1, 86) ¼ 3.3,

po0.07 and F(1, 86) ¼ 0.15, po0.7, respectively. Moreover, the context " familiarity and the context " participant’s gender " familiarity interactions were significant,

F(1, 86) ¼ 5.6, po0.01, F(1, 86) ¼ 16.3, po0.0001, respectively. To analyse this significant three-way interaction, we

ran two-way ANOVAs with context and participant’s

gender as factors for each product type taken separately.

For the familiar products, we observed a significant context

x gender interaction, F(1, 86) ¼ 4.7, po0.05. This interaction was due to the gender effect obtained in the non-social

context, F(1, 86) ¼ 6.0, po0.01, but not in the neutral

social context, F(1, 86) ¼ 1.8, po0.2 (the first four bars in

Fig. 5a). Taking each gender separately and considering

familiar products, the desire of men to eat in the presence

of a neutral face did not significantly differ from the desire

to eat in the non-social context, F(1, 43) ¼ 2.4, po0.2 (the

first and third bars in Fig. 5a). The same result was

observed in women, F(1, 43) ¼ 2.5, po0.2 (the second and

fourth bars in Fig. 5a).

For the unfamiliar products, only the social context

effect was significant, F(1, 86) ¼ 8.5, po0.001. Regardless

of the participants’ gender, the desire to eat unfamiliar

meats was higher when presented in the neutral social

context than in the non-social context (the first four bars in

Fig. 5b).

Non-social versus social contexts: faces expressing pleasure

The main effects of social context and product familiarity were highly significant, and that of participant’s

gender just significant: F(1, 86) ¼ 14.4, po0.001, F(1,

86) ¼ 14.4, po0.001 and F(1, 86) ¼ 4.0, po0.05, respectively. However, the context " familiarity interaction, as

well as the context " familiarity " participant’s gender

interaction were also significant: F(1, 86) ¼ 3.95, po0.05,

F(1, 86) ¼ 14.9, po0.001. When the products were

familiar, men liked them more than women, as seen above

in the non-social condition, F(1, 86) ¼ 6.0, po0.01, but

this gender difference disappeared when presented in a

pleasant social context, F(1, 86) ¼ 2.4, po0.2 (the first two

bars and the fifth and sixth bars in Fig. 5a). For men, the

context did not influence the desire score, F(1, 43) ¼ 0.15,

po0.7 (the first and fifth bars in Fig. 5a), whereas for

women, the pleasant faces increased the scores compared

to the non-social context, F(1, 43) ¼ 7.46, po0.01 (the

second and sixth bars in Fig. 5a). Conversely, when the

products were unfamiliar, there was no significant gender

difference in the non-social context, F(1, 86) ¼ 1.8, po0.2

(the first two bars in Fig. 5b). However, the gender

difference appeared when meats were presented in a

pleasant social context, F(1, 86) ¼ 4.0, po0.05 (the fifth

and sixth bars in Fig. 5b). Moreover, the changes in desire

to eat unfamiliar meat products in the presence of other

people expressing pleasure compared to the non-social

context was greater in men than in women: F(1, 43) ¼ 15.8,

po0.001 and F(1, 43) ¼ 4.5, po0.05, respectively.

Non-social versus social contexts: faces expressing disgust

The main effects of participant’s gender, social context

and their interaction were not significant: F(1, 86) ¼ 2.8,

po0.1, F(1, 86) ¼ 0.1, po0.8 and F(1, 86) ¼ 0.9, po0.4,

respectively. However, the context " familiarity and context " familiarity " participant’s gender interactions were

highly significant: F(1, 86) ¼ 9.3, po0.01 and F(1,

86) ¼ 12.3, po0.001. For familiar products, we observed

ARTICLE IN PRESS

7

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

Men

7

Women

6

Desire score

5

4

3

2

1

0

Non social

Neutrality

Pleasure

Disgust

Context

7

6

Men

Women

Desire score

5

4

3

2

1

0

Non social

Neutrality

Pleasure

Disgust

Context

Fig. 5. Effect of the neutral, pleasant and disgust social contexts compared to the non-social context on the desire to eat (a) familiar meats and (b)

unfamiliar meats in male and female participants. (Mean7Confidence Interval: 95%). – – – Line showing men’s desire to eat in non social context. – – –

Line showing women’s desire to eat in non social context.

a significant gender " context interaction. As for neutrality

and pleasure, there was a significant difference between

men and women in the non-social context, with women

having less desire to eat meat in this latter condition, but

not when meats were presented in a disgust social context,

F(1, 86) ¼ 1.2, po0.3 (the seventh and eighth bars in

Fig. 5a). This was due to the decreased desire of men to eat

familiar meat in the presence of disgusted faces, compared

to the non-social context, F(1, 43) ¼ 9.8, po0.01, whereas

the women maintained their lower desire to eat meat, F(1,

43) ¼ 0.17, po0.7. In contrast, no effect of gender, context

or their interaction was significant in the case of the

unfamiliar products. Thus, for the unfamiliar products, the

desire to eat meat remained low both in and not in the

presence of faces expressing disgust.

Comparison of the three emotional facial expressions on

desire to eat meat in the social context

The main effects of emotional facial expressions

(neutrality, pleasure and disgust) and of product familiarity

were highly significant on the desire to eat, F(2,

172) ¼ 13.3, po0.001 and F(1, 86) ¼ 78.5, po0.0001, but

the participant’s gender and eater’s gender had no major

effect. No two-way, three-way or four-way interactions

ARTICLE IN PRESS

8

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

were significant except the familiarity " eater’s gender

interaction, F(1, 86) ¼ 5.6, po0.05. Thus, in the social

context, regardless of the facial emotion perceived, the

familiar meat products were preferred to unfamiliar meat

products (means 4.8 vs. 3.1). As expected, the two-by-two

face comparison showed that the disgusted faces produced

lower eating desire scores than those expressing pleasure

(means 3.7 vs. 4.2), F(1, 86) ¼ 14.6, po0.001 or neutrality

(means 3.7 vs. 3.9), F(1, 86) ¼ 11.1, po0.001. In contrast,

the faces expressing pleasure increased the level of eating

desire, compared to neutral facial expressions (means 4.2

vs. 3.9), F(1, 86) ¼ 11.8, po0.001. Moreover, the significant familiarity " eater’s gender interaction indicated that

regardless of the participants’ gender, unfamiliar meat

products received a higher eating desire score when a male

eater was shown (means 3.2 vs. 3.0), F(1, 86) ¼ 8.77,

p ¼ 0.004, whereas no difference between male and female

eaters was observed for the familiar products (means 4.8 vs.

4.8), F(1, 86) ¼ 0.03, p ¼ 0.86.

Discussion

In the non-social context, the present study showed that

the desire to eat meat was greater in men than in women in

the specific case of familiar meat products. This lower

desire in women might result from either disgust towards

sensory characteristics of meat or be related to health,

weight and/or ethical concerns (Audebert, Deiss, &

Rousset, 2006; Kubberød, Ueland, Roodbotten, Westad,

& Risvik, 2002; Lea & Worsley, 2002; Rousset, Deiss,

Juillard, Schlich, & Droit-Volet, 2005). Indeed, some

women reported disliking meat for its red colour, presence

of blood and the flesh that reminded them of dead animals

(Kubberød, Dingstad, Ueland, & Risvik, 2006; Lupton,

1996; Mooney & Walbourn, 2001). However, our study

revealed that when the meat products were unfamiliar, the

desire to eat meat also decreased in men who generally

liked meat, to the point that there was no longer any

observable difference between women and men in their

eating desire. This result was consistent with those showing

that lower liking is often observable for unfamiliar foods

and particularly unfamiliar meat products (Pliner &

Hobden, 1992; Pliner & Pelchat, 1991; Pliner et al., 1998).

It is of particular interest that our study suggested that

the perception of another person’s face modified the desire

to eat meat in both men and women. The present study

revealed that the observation of an unknown eater, even if

expressing a neutral emotion, increased the desire to eat

meat, and this to a greater extent for unfamiliar meat

products. Watching another person eating was thus

sufficient to increase the desire to eat. This result is

consistent with the modelling studies in which the model’s

behaviour (who ate more or less) influenced the amount of

food eaten by the participant who imitated the model’s

behaviour, independent of whether or not the participant

was on a diet or hungry (Goldman, Herman, & Polivy,

1991; Rosenthal & McSweeney, 1979). Although our study

deals with the desire to eat and not with the amount of

food eaten, it provided results consistent those of studies

showing the widely observed inclination of individuals to

eat in the same way as others did. According to Leary,

Tchividijian, and Kratxberger (1994), social intake norms

may be a strong determinant of eater’s behaviour, probably

stronger than physiological signals (hunger, satiety).

However, as stated by Herman et al. (2003), the modelling

effects remain a mystery.

The main contribution of our study was to demonstrate

that not only the presence of the eater models but the

emotion that they expressed affected the participants’

desire to eat. Indeed, the participants wanted to eat the

meat products more when they viewed the models with

expressions of pleasure than with neutral expressions.

Conversely, they had less desire to eat meat products when

the models showed expressions of disgust rather than

neutral ones. Thus, the pleasure faces could have suggested

to the participants that the food tasted good, and the

disgusted faces could have suggested that the food tasted

bad. Consciousness of such information should increase or

decrease individuals’ willingness to taste foods. However,

as explained in the introduction, a more automatic and less

conscious process could also be involved. According to

embodiment theory, the observation of emotions expressed

by other people’s faces induced the physiological reactions

associated with this emotion in the individuals (Barsalou et

al., 2003; Niedenthal et al., 2005). As suggested by

Dimberg (1982, 1990), the perception of positive and

negative facial expressions induces spontaneous mimicry

that in turn produces the corresponding emotional state

and influences the emotional attitude towards the context.

Thus, via an imitation process, the facial expressions of

others play an important role on our own emotions

(Adolphs et al., 2000; Décety & Chaminade, 2003; Gallese,

2003). Further investigations using electromyography

methods are now required in order to test whether eater

models’ facial expressions induce facial reactions in the

participants. Such a study might prove that the emotion

perceived in other people modulates the emotion elicited by

the food products themselves.

Our study also suggested that the influence of facial

expression on the desire to eat depended on the type of

food products and on the participant’s gender. In the case

of familiar meat products, compared to the eating desire

assessed in the non-social context, our results revealed that

positive emotion increased the desire to eat in the subjects

expressing a low eating desire (i.e., women), and the

negative emotion decreased this desire in the subjects

expressing a high eating desire (i.e., men). However, the

desire level in the presence of pleasant faces did not change

when the subjects (i.e., men) already liked the products. In

the same way, the desire level in the presence of disgusted

faces did not change when the subjects (i.e., women)

disliked them.

Regarding the desire of eating unfamiliar products in the

non-social context, the scores were similarly low in men

ARTICLE IN PRESS

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

and women (lower than 3 out of 10). In the social context

of faces expressing pleasure, the scores given by men and

women were improved. However, men increased their

scores more than women. Thus, in a non-familiar situation

of unfamiliar food, men were more influenced by positive

facial information than women were. This raises the

question of the stronger inclination of men to follow the

group than women in the case of unfamiliar food products.

On the one hand, Klesges, Bartsch, Norwood, Kautzman,

and Haugrud (1984) found that social facilitation of eating

(increase in eating in the presence of others) is generally

stronger in men than in women. Moreover, one study by

Hobden and Pliner (1995) showed that when participants

had to choose between a novel and a familiar food product,

men chose novel foods more often than women, which is

consistent with our data. The behaviour of men towards

unfamiliar food may also be associated with their lower

risk perception in general. Men are less afraid, assess most

risks lower and worry about them less than women (Fagerli

& Wandel, 1999; Williams & Hammitt, 2001). Another

plausible reason might be that men may be more prone to

test unfamiliar meat because they like meat in general. In

contrast, women were more influenced by positive emotions for familiar rather than non-familiar meat products.

Because they did not like meat a lot, they might have had

little desire to try unfamiliar meat.

Surprisingly enough, the present study also suggested

that the social influence on the desire to eat meat products

varied as a function of the gender of the model observed.

Indeed, regardless of the participant’s gender, unfamiliar

meat products were judged as more desirable when the

other person eating these products was a man instead of a

woman. Few studies of social learning in humans have

considered the roles played by the gender of the individual

(Choleris & Kavaliers, 1999). As regards human eating

behaviour, Mory, Chaiken, and Pliner (1987) showed that

participants ate less when the eating companion was of the

opposite sex. Moreover, Pliner and Chaiken (1990) showed

that women ate less when the eating companion was a man

and when he was most desirable. Their behaviour may be

attributed to an attempt to convey an impression of

femininity. However, no study has yet focused on the

gender effect on desire/consumption of an unfamiliar food.

In the case of animals, Kawamura (1959) studied the

transmission of unfamiliar behaviours in Japanese monkeys, which suggested the existence of social constraints on

the channelling of socially mediated learning. When a

unfamiliar behaviour was invented by an adult male and

subsequently acquired by the dominant male, its transmission through the group was faster.

In conclusion, our study showed the influence of social

context on desire to eat meat products. Moreover, this

influence differed according to the familiarity of the

concerned food, the desire to eat meat products in a nonsocial context and the participant’s gender. Men were more

easily influenced than women by the social context of

pleasure in the case of unfamiliar meats, for which the

9

desire score was low in a non-social context. In contrast,

the social influence was stronger for women on their desire

to eat familiar rather than unfamiliar meats. Thus, it might

be easier to improve their desire to eat meat by using social

influence rather than by creating unfamiliar meat products.

Future research should seek to determine the effect of

facial expressions on the desire to eat a wider range of

foods such as palatable versus less palatable food products.

Further experiments should be done to compare the impact

of emotion and social context not only on the desire to eat,

but also on food liking in relation to consumption.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Benjamin Charpy for his valuable

photographic work, to E. Juillard for her technical

assistance, and to Stephanie Meritet and Alexandra

Tabouji-Beji (graduate students in ‘Statistics and data

treatment’) for the statistical analyses. This work was

supported by two grants, one from the Regional Council of

Burgundy and INRA DADP, and the second from the

Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Blan06-2-145908

FaceExpress).

References

Adolphs, R., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., Cooper, G., & Damasio, A. R.

(2000). A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of

emotion revealed by three dimensional lesion mapping. Journal of

Neuroscience, 20, 2683–2690.

Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (2003). Dissociable neural

systems for recognizing emotions. Brain and Cognition, 52, 61–69.

Audebert, O., Deiss, V., & Rousset, S. (2006). Hedonism as a predictor of

attitudes of young French women towards meat. Appetite, 46,

239–247.

Barsalou, L., Nidenthal, P., Barbey, K., & Ruppert, J. (2003). Social

embodiment. In B. H. Ross (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and

Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory, vol. 43 (pp. 43–92). San

Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Birch, L. L. (1980). Effects of peer models’ food choices and eating

behaviors on preschoolers’ food preferences. Child Development, 51(2),

489–496.

Choleris, E., & Kavaliers, M. (1999). Social learning in animals: gender

differences and neurobiologiacal analysis. Pharmacology Biochemistry

& Behavior, 64(4), 767–776.

Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the

physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience,

3(8), 655–666.

Decety, J., & Chaminade, T. (2003). Neural correlates of feeling sympathy.

Neuropsychologia Special Issue on Social Cognition, 41, 127–138.

Dimberg, U. (1982). Facial reactions to facial expressions. Psychophysiology, 19, 643–647.

Dimberg, U. (1990). Facial electromyography and emotional reactions.

Psychophysiology, 27, 481–494.

Durrett, R., & Levin, S. A. (2005). Can stable social groups be maintained

by homophilus imitation alone? Journal of Economic Behavior &

Organization, 57, 267–286.

Ekman, P., Levenson, R. W., & Friesen, W. V. (1983). Autonomic nervous

system activity distinguishes among emotions. Science, 221,

1208–1210.

Eertmans, A., Baeyens, F., & Van den Bergh, O. (2001). Food likes and

their relatives importance in human eating behaviour: Review and

ARTICLE IN PRESS

10

S. Rousset et al. / Appetite ] (]]]]) ]]]–]]]

preliminary suggestions for health promotion. Health Education

Research, 16(4), 443–456.

Fagerli, R. A., & Wandel, M. (1999). Gender differences in opinions and

practices with regards to a healthy diet. Appetite, 32, 171–190.

Gallese, V. (2003). The roots of empathy: The shared manifold hypothesis

and the neural basis of intersubjectivity. Psychopathology, 36,

171–180.

Gallese, V. (2005). The intentional attunement hypothesis the mirror

neuron system and its role in interpersonal relations. Lecture Notes in

Artificial Intelligence, 3575, 19–30.

Goldman, S. J., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (1991). Is the effect

of social model on eating attenuated by hunger? Appetite, 17,

129–140.

Harper, L. V., & Sanders, K. M. (1975). The effect of adults’eating on

young children’s acceptance of novel foods. Journal of Experimental

Child Psychology, 20, 206–214.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional

Contagion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Herman, C. P., Roth, D. A., & Polivy, J. (2003). Effects of the presence of

others on food intake: a normative interpretation. Psychological

Bulletin, 129(6), 873–886.

Hobden, K., & Pliner, P. (1995). Effects of a model on food neophobia in

humans. Appetite, 25, 101–114.

Kawamura, S. (1959). The process of sub-culture propagation among

Japanese macaques. Primates, 2, 43–54.

Klesges, R. C., Bartsch, D., Norwood, J. D., Kautzman, D., & Haugrud,

S. (1984). The effects of selected social variables on the eating

behaviour of adults in the natural environnements. International

Journal of Eating Disorders, 3, 35–41.

Kubberød, E., Dingstad, G. I., Ueland, O., & Risvik, E. (2006). The effect

of animality on disgust response at the prospect of meat preparation—

An experimental approach from Norway. Food Quality and Preference,

17(3 & 4), 199–208.

Kubberød, E., Ueland, O., Roodbotten, M., Westad, F., & Risvik, E.

(2002). Gender specific preferences and attitudes towards meat. Food

Quality and Preference, 13(5), 285–294.

Lea, E., & Worsley, A. (2002). The cognitive contexts of beliefs about

healthiness of meat. Public Health Nutrition, 5, 37–45.

Leary, M. R., Tchividijian, L. R., & Kratxberger, B. E. (1994). Selfpresentation can be hazardous to your health: Impression management

and health risk. Health Psychology, 13, 461–470.

Lewin, B. K. (1958). Group decision and social change. In E. E. Maccoby,

T. Newcomb, & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in Social Psychology

(pp. 197–219). New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Toronto: Holt,

Rinehart, Winston.

Lewin, B. K., & Grabbe, P. (1945). Problems of re-education. Journal of

Social Issues(3).

Lupton, D. (1996). Food, the Body and the Self. London: SAGE

Publications.

Martins, Y., Pelchat, M., & Pliner, P. (1997). ‘‘Try it; it’s good and it’s

good for you’’: effects of taste and nutrition on willingness to try novel

foods. Appetite, 28, 89–102.

Meiselman, H. L. & Rivlin, (1986). Measurement of food habits in taste

and smell disorders. In: Meiselman, H.L. & Rivlin, R.S. (eds.), Clinical

Measurements of Taste and Smell (pp. 229–248).

Mooney, K. M., & Walbourn, L. (2001). When college students reject

food: not just a matter of taste. Appetite, 36(1), 41–50.

Mory, D., Chaiken, S., & Pliner, P. (1987). ‘‘Eating lightly’’ and the selfpresentation of feminity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

53, 693–702.

Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., &

Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in attitudes, social perception and

emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 184–211.

Phillips, M. L., Young, A. W., Scott, S. K., Calder, A. J., Andrew, C.,

Giampietro, V., et al. (1998). Neural responses to facial and vocal

expressions of fear and disgust. Proceedings of the Royal Society of

London Series B—Biological Sciences, 265(1408), 1809–1817.

Pliner, P. (1982). The effect of mere exposure on liking for edible

substances. Appetite, 3(3), 283–290.

Pliner, P., & Chaiken, S. (1990). Eating, social motives, and selfpresentation in women and men. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 20, 240–254.

Pliner, P., & Hobden, K. (1992). Development of a scale to measure the

trait of food neophobia. Appetite, 19(2), 105–120.

Pliner, P., Latheenmaki, L., & Tuorila, H. (1998). Correlates of human

food neophobia. Appetite, 30, 93.

Pliner, P., & Pelchat, M. (1991). Neophobia in humans and the special

status of foods of animal origin. Appetite, 16, 205–218.

Rizzolati, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (2002). From mirror

neurons to imitation: Facts and speculations. In A. N. Meltzoff, & W.

Prinz (Eds.), The Imitative Mind: Development, Evolution, and Brain

Bases. Cambridge Studies in Cognitive and Perceptual Development (pp.

247–266). New York: Cambridge University press.

Rosenthal, B., & McSweeney, F. K. (1979). Modeling influences on eating

behavior. Addictive Behaviours, 4, 205–214.

Rousset, S., Deiss, V., Juillard, E., Schlich, P., & Droit-Volet, S. (2005).

Emotions generated by meat and other food products in women.

British Journal of Nutrition, 94, 1–12.

Rozin, P. (1990). Development in the food domain. Developmental

Psychology, 26, 555–562.

Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. (1980). The psychological categorization of foods

and non-foods: A preliminary taxonomy of food rejection. Appetite, 1,

193–201.

Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J., Kaube, H., Dolan, R. J., & Frith,

C. D. (2004). Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory

components of pain. Science, 303(5661), 1157–1162.

Williams, P. R. D., & Hammitt, J. K. (2001). Perceived risks of

conventional and organic produce: Pesticides, pathogens, and natural

toxins. Risk Analysis, 21, 319–330.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1–27.

Zajonc, R. B., Markus, H., & Wilson, W. R. (1974). Exposure effects and

associative learning. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10,

248–263.