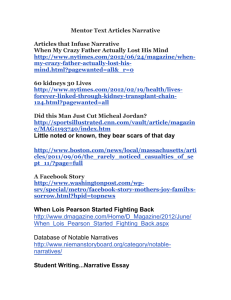

Strategies of Narrative Synthesis in American History

advertisement