\\Justice\shared\00 Bob\Articles\Or Corp Book 2011\2013 Web

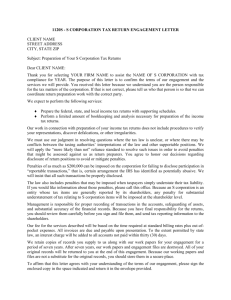

advertisement