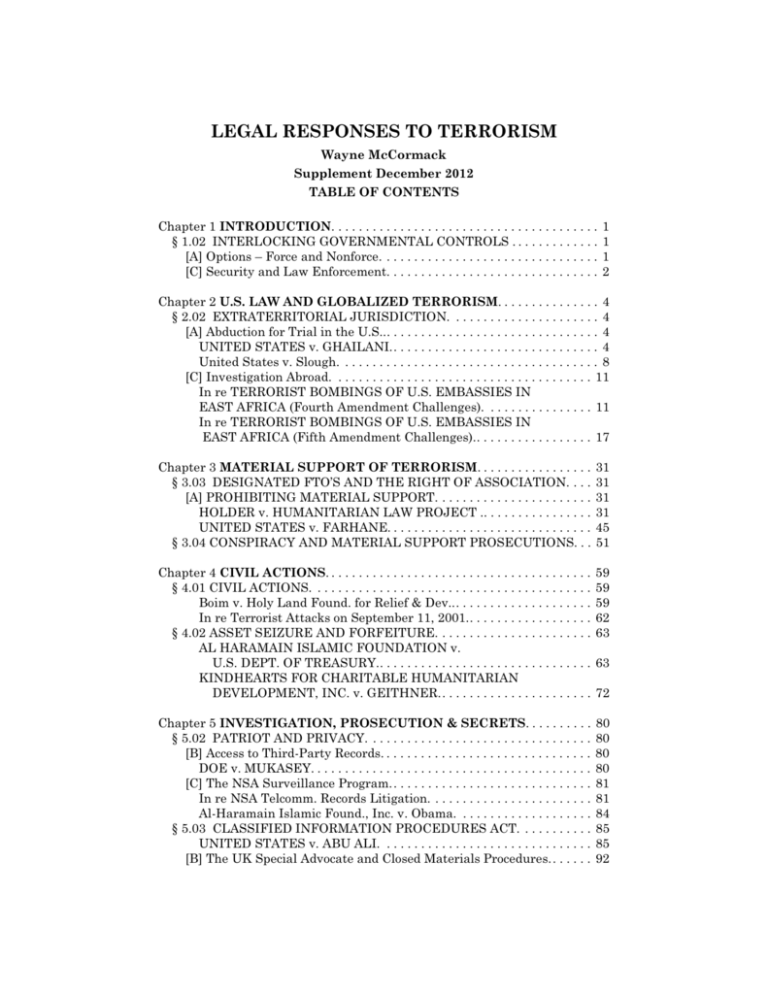

legal responses to terrorism

advertisement