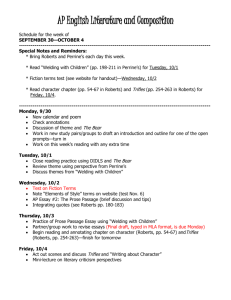

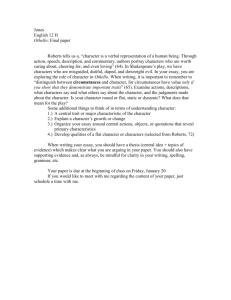

Blair O'Connor TAH Grant Final Project/Book Review Founding

advertisement

Blair O’Connor TAH Grant Final Project/Book Review Founding Mothers: The Women Who Raised Our Nation Almost every American is familiar with the heroic stories of the founding men who bravely declared independence from Great Britain, fought the American Revolution, and created the US Constitution. But few know the significant and often unsung role that women played in helping to raise the nascent nation. In the book Founding Mothers, bestselling author and journalist Cokie Roberts retells the story of the American Revolution and the founding of the nation with a focus on the women involved. By using the personal letters, journals, plays, and poems of several key women who left their written documents behind, Roberts details the lives and activities of the remarkable wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters who encouraged, helped, and advised the famous “Founding Fathers.” Although the book has some significant flaws, it does offer some fascinating glimpses of women like Eliza Pinckey, Deborah Reed Franklin, Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail Adams, Martha Washington, and other dedicated and patriotic women who supported and influenced the men who are credited with creating the nation and helping the country survive. In a casual tone, Roberts recounts the stories of these women intermittently in rough chronological order from the prelude to the Revolution until the end of Washington’s second term as President. While this technique illustrates the interactions and convoluted relationships between this elite circle of women (and the men they corresponded with), it often becomes jumbled and confusing. Roberts frequently goes off on tangents and does not always transition well between the narrative and her sometimes distracting asides. The result is that it comes across more like a random collection of stories about the women involved, sometimes full of extraneous detail, rather than reading as a comprehensive historical account. While many readers may appreciate her casual tone and interesting asides, the changes in tone (ranging from informal to colloquial), rough transitioning, and interjections like “Phew!” and “Wow!” are often distracting, confusing, and sometimes annoying. Nevertheless, the book does contain some valuable information about the women who significantly contributed to the founding of the United States. The book starts off strong in the first chapter, “Before 1775: The Road to the Revolution,” as Roberts does a nice job of relaying some background information about the everyday lives of colonial women in the midst of describing the specific contributions of women like Eliza Pinckney, Esther Burr, and Deborah Reed Franklin. She first details the extraordinary experience of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, the mother of two foundersCharles Cotesworth Pinckney and Thomas Pinckney- and the exceptional woman who, at the age of sixteen, was left in charge of her family’s plantations in South Carolina. And, as Roberts points out, “Not only did she oversee the planting and harvesting of the crops on the plantations, but she also taught her sister and some of the slave children, pursued her own intellectual education in French and English, and even took to lawyering to help poor neighbors.” (2) As if that were not enough, Eliza was also the brain behind an indigo experiment that, despite the ridicule of her neighbors, eventually became a considerable source of wealth (and importance to the Mother Country) for the colony of South Carolina. (6) Roberts then segways from Eliza’s exceptional life by contrasting it with the many colonial women who did not have the advantages and legal rights of Ms. Pinckney. Next, Roberts attempts to explain why the infamous Aaron Burr “ended up as the villain in the founding stories” by describing the experiences of his family, most notably his mother, Esther Edwards Burr, whose letters “give us some sense of how the women of the time felt about the constant childbearing, the loneliness of being cut off from female friends and family, and, as always, the ever-present duty” in addition to the religious and political issues of the poorly protected colonies. (17) Lastly, Roberts devotes a section of the first chapter to Deborah Read Franklin, the over-worked and often underappreciated “wife” of Ben Franklin. She describes how Deborah ran a sundry shop in the front of the house and helped with Ben’s printing shop in the back while raising Ben’s son William and eventually taking over the postal service and defending her doorstep from an angry mob, all while her husband was away on business enjoying London. (28-29). Roberts concludes that it was because of the sacrifices made by women like Deborah Read Franklin in the years leading up to the war that allowed the men in their lives to succeed and carry on with their affairs in early American politics. In the second chapter, “1775-1776: Independence,” Roberts explains the important role women played in organizing boycotts of British goods and promoting “homespun” clothing and “Liberty Tea” in response to what many Americans were beginning to see as “oppressive rule by England.” She points out that “as shoppers, women were key participants in the movement to shun British goods.” (38) She then explains the influential role that women played in the decision of the men to declare independence, focusing specifically on the most famous female pamphleteer and propagandist of the time, Mercy Otis Warren. She shows how Warren’s anonymously written plays, poems, and personal letters helped to foster and fuel the cause for liberty among the colonists. She expresses that “Mercy Warren must have known she played no small part in accomplishing that remarkable end. Her poems and plays and pamphlets helped sway public opinion to take up arms against the Mother Country.” (59-60) Also, in this section, Roberts points out that the signers of the Declaration turned to a woman – Mary Katherine Goddard – who printed the famous document, “becoming herself a signer of sorts , firmly associating herself with the dangerous cause of the new nation.” (45) Roberts then goes into the fascinating life of the “political philosopher” and “Founding Mother,” Abigail Adams. She draws heavily upon the letters between John and Abigail to show the indispensable role Abigail played in John’s life as he increasing depended on his remarkable wife for just about everything. She shows how John “turned over decisions about running the farm and educating the children to Abigail, who was forced to cope even as she watched the British readying for war.” (65) Abigail gave political advice, listened to her husband’s frustrations, and provided John with peace of mind by “running things well at home and supporting his endeavors, even though she missed him terribly.” (74) And John was well-aware that his wife was indeed remarkable, as he expressed to her that “it gives me more pleasure than I can express to learn that you sustain with so much fortitude the shocks and terrors of the times. You really are brave, my dear, you are a heroine.” (68) As for Abigail, she saw her work as “her contribution to the cause, a gift that made it possible for John to serve the country.” (74) John, and the other influential men of the time, simply could not have done what they did without the women in their lives. The next two chapters, “1776-1778: War & a Nascent Nation” and “1778-1782: Still More War & Home-Front Activism,” start to become muddled as Roberts describes the experiences of several different women both on the front lines and on the home-front during the Revolutionary War. She explains that “in addition to the legions of women taking over for their husbands at home, often under perilous circumstances, [and those who followed their men to camp], there were genuine Revolutionary War heroines – women who served as soldiers and spies, women who tricked the enemy, women who were tricked by the enemy.” (78) Throughout chapter three, she describes the various ways in which women helped the American patriots as camp followers, spies, and imparters of crucial information to the Continental Army. On a few occasions, women, like Deborah Sampson, even disguised themselves as men and fought alongside their male brethren during the war. (82) She then chronicles the crucial roles that the generals’ wives – Martha Washington, Lucy Knox, and Kitty Greene – played in supporting their husbands and the troops at camp. Despite the difficulties of leaving their children behind and living in army camps, all three women were essential to helping to minister to the troops, provide entertainment, and raise morale at crucial times throughout the difficult conflict. Roberts ends the third chapter with and devotes the entire fourth chapter to the women who defended their homes and families, relayed information to men in Congress and the military, raised money for the troops, and created diversions for the British from the home-front. Roberts recounts how many women, like Eliza Pinckney and Mary Bartlett, and their families were displaced as the British advanced upon their communities and saw their own homes destroyed as the British came looking for their men and any information about them. In Chapter Four, Roberts also highlights the political activism of women like Esther Reed and Ben Franklin’s daughter Sarah Bache, who organized a drive to raise money for Washington’s troops at Valley Forge. She explains that Reed wrote the famous patriotic article, “Sentiments of an American Woman,” which was printed in several newspapers and called on women to wear simpler clothing, dress less elegantly, and give the money saved to the troops as “the offering of the ladies” (124) and was then elected to lead the Ladies’ Association of Philadelphia, whose fundraising efforts spread to several other states where women organized for the “purpose of promoting a subscription for the relief and encouragement of those brave men in the Continental Army.” (126) In the midst of discussing these efforts and the problems faced by the generals’ wives at camp, Roberts also uncovers the infamous role Peggy Arnold played in her husband’s traitorous actions against the Americans. She argues that Peggy, despite fooling many of the founders, was influential in driving her husband Benedict to strike his “nefarious deal” with the British and was a willing conspirator in helping to pass information along to the enemy. In the next chapter, “1782-1787: Peace & Diplomacy,” Roberts summarizes the ending of the war, the impatient awaiting of a final peace with Great Britain, and the experiences of the “wives and daughters of diplomacy.” Again, the writing is disorganized and the stories of the women involved - Jane Metcom (Ben Franklin’s sister), Sally Livingston Jay (wife of diplomat John Jay), Martha Laurens (daughter of minister to Holland Henry Laurens), Abigail Adams, and Polly Jefferson (young daughter of Thomas Jefferson) – get lost in the jumbled narrative and poor transiting between different people and ideas. Somehow, in the middle of all of these elite women’s stories, Roberts manages to throw in an interesting aside about Elizabeth Freeman, also known as “Mumbet,” a slave woman who sued for (and won) her freedom under the Massachusetts constitution that John Adams helped to create. (154) Interestingly, a female slave story that Roberts does not elaborate much on is that of Sally Hemmings, who accompanied Thomas Jefferson’s young daughter Polly to France and eventually became involved in a sexual relationship with (and bore the children of) Mr. Jefferson. However, all Roberts mentions about her is that “when [Polly] woke up, the nine-year-old found herself at sea, with only Sally Hemmings, a fourteen-year-old slave, as a companion” (184) and that Abigail thought Sally Hemmings should return to Virginia. (185) It is disappointing that the author does not elaborate more in this topic, especially when she feels free to make unnecessary and rambling asides about other notso-interesting or relevant transgressions. In Chapter Six, “1787-1789: Constitution & the First Election,” Roberts again gives a rough summary of what the men were doing and throws in some information about Annis Stockton (famous poet mentioned somewhere earlier in the book), who “hosted some of the most important politicians of the day, including George and Martha Washington, at Morven [her mansion in New Jersey] and continued to write her poetry,” (187) and Martha Washington, who juggled taking care of all the family members and “constant parade of visitors” at Mount Vernon. The author then discusses at length the family history of Elizabeth “Betsy” Schuyler and her marriage to Alexander Hamilton. Roberts remarks that Betsy was “an excellent match for Hamilton. It was not just he married into wealth and power; Betsy’s devotion and good sense supported him for years … Had she been any other than what she was, despite all his genius and force of character, Hamilton could never have attained the place he did.” (194) Also in this very long and dense chapter, Roberts: mentions the burdens of entertaining and attending to guests that women like Sally Bache (Franklin’s daughter) and Molly Morris (wife of Robert Morris, the so-called financier of the Revolution) had to endure during the Constitutional Convention and the years immediately after; details the controversial marriage of Gouverneur Morris (writer of the Constitution) to the scandalous Anne (“Nancy”) Cary Randolph; and revisits Mercy Otis Warren, who was now an ardent Anti-Federalist publishing works opposing ratification under the pseudonym “A Columbian Patriot.” (220) In the last chapter, “After 1789: Raising a Nation,” author Cokie Roberts describes the importance of the official entertaining and formal dinners held by several of the “Founding Mothers.” While Martha Washington was responsible for most of the gatherings, including her “public day” on Fridays, other women also hosted weekly events. Abigail Adams instituted her own Monday-night receptions and Wednesday dinners; Lucy Know (whose husband was now Secretary of War) hosted gatherings on Wednesdays; Sally Jay (wife of the now-Chief Justice) entertained on Thursdays; and the wife of the British consulate did so on Tuesdays. (234) As Roberts remarks, “Though much of it sounds silly, these weekly events served a purpose. Their formality seemed appropriate to diplomats and dignitaries accustomed to royal courts abroad. But they were open to all well-dressed comers, lending a democratic air to what came to be called the republican court.” (234) Furthermore, as Roberts explains, these receptions and dinners provided places for politicians to come together outside of the walls of Congress and do important political business. In fact, it was at a dinner party hosted by Jefferson that the famous deal of debt assumption and the moving of the nation’s capital to the South was brokered. (240) Also in this chapter, Roberts highlights Washington’s favorable comments about the “ladies” he met during his tours of the northeast and the south. And, she details Kitty Greene’s hardships after the war and her successful petition to Congress for repayment of her husband’s war expenses. Most surprisingly, Roberts also reveals that it was Kitty Greene who supported and encouraged Eli Whitney, who was originally hired as a tutor, to develop his legendary cotton gin. As Roberts notes, “Eli Whitney could not have developed the cotton gin without Greene’s advice. In fact, some believe that Whitney stole the credit for what was essentially Greene’s invention.” (249) Another interesting tidbit brought up in this final chapter is the role that a woman - Eliza Powell - played in persuading George Washington to run for a second term. Finally, Roberts end the book by summarizing the second election and the passing of the presidency onto John Adams. She ends the book well by crediting the success of the nation in part to the efforts of the women involved and quotes Washington’s words of recognition to poet Annis Stockton: “I [would not] rob the fairer sex of their share in the glory of a revolution so honorable to the human nature, for indeed, I think you ladies are in the number of the best patriots America can boast.” A nice praise of the role of women by the Founding Father himself. In all, Founding Mothers offers some intriguing details about several women of the Revolutionary period and the significant roles they played in shaping the fledging nation. However, it could have been better written and much better organized. The rough chronology, distracting asides, and abrupt changes in tone and topics detract from the work and often cause the stories to become confusing and muddled. Even Roberts’ conclusion that there was “nothing unique about them” and that these exemplary women simply “put one foot in front of the other in remarkable circumstances [and] carried on,” (xx) is debatable and somewhat contradictory to the evidence and anecdotes presented throughout the book. If I could recommend only one book to someone interested in reading about women during this extraordinary period of American history, I would suggest Carol Berkin’s Revolutionary Mothers over this book. Berkin’s book is far better written, much better organized, and more comprehensive. It not only contains equally fascinating accounts of the elite women mentioned in Roberts’ Founding Mothers, it also includes noteworthy sections about the roles and experiences of loyalist, Native American, and African American women, as well as a chapter on the legacy/impact of the Revolution on women’s role in American history.