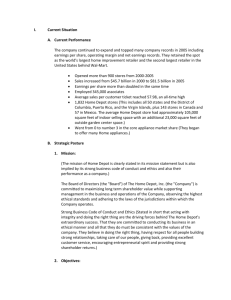

Chapter 12 Nardelli and Home Depot “The customer is King” Marcus

advertisement