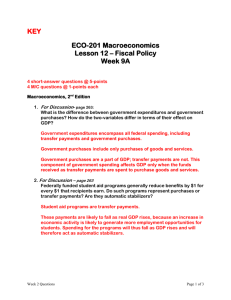

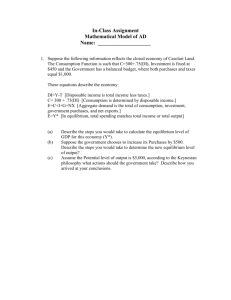

The Effects of Government Purchases Shocks: Review and

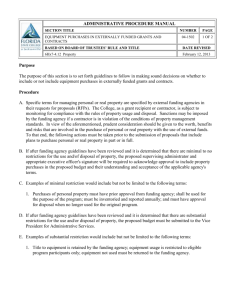

advertisement