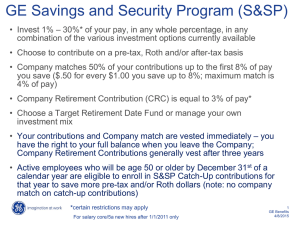

Improving tax incentives for retirement savings

advertisement