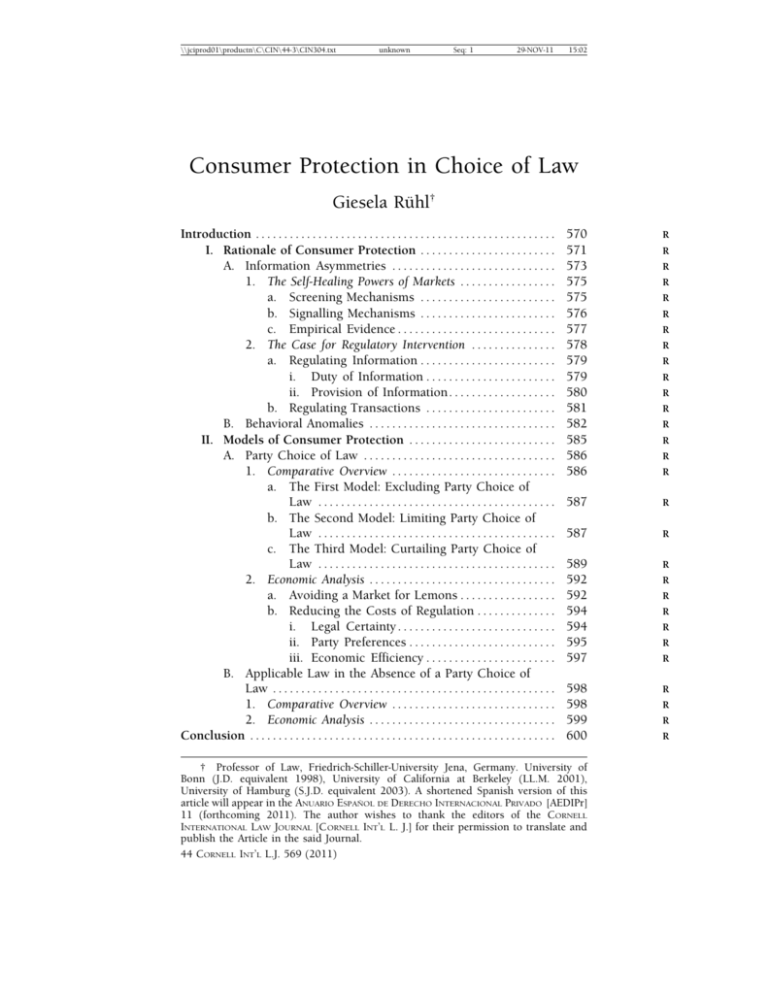

Consumer Protection in Choice of Law

advertisement