Chapter One Introduction

Chapter One

Introduction

The importance of history to me is simply to find out

who you are and where you’ve been. It becomes doubly

important if someone else has been writing your history.

I think Blacks in America need to re-examine their time

spent here to see the choices that were made as a people.

—August Wilson, qtd. in Powers 52

As a prominent African American playwright, August Wilson has always been interested in the exploration and exploitation of black cultural experience in his plays.

He is convinced, “those who wrote history books have misrepresented the role of black people in the country’s making” (Shannon, Vision 8). For a long period of suffering and oppression caused by slavery and especially racial discrimination, the black people have lost faith in their cultural values and subjected themselves to indignity. In order to give voice to this oppressed group and arouse black consciousness, Wilson obtains materials from a fusion of history and his personal life and imagination. He sees the past as a rich repository of synthesizing power, which can provide a useful guide for the present and the future. Through writing on the unexplored landscape of black experience, Wilson’s literary objective aims to give

African American history a real status. Moreover, in an interview with Samuel

Freedman, he optimistically expresses his ideal target for the individual:

I concretize the values of that [black] tradition, placing them in action in

order to demonstrate their existence, their ability to offer and provide

sustenance for a man once he’s left his father’s house—so that you’re not

in the world alone, so that you have values that will guide you in your

life. (qtd. in Shannon, Vision 7)

He hopes his works will serve as a history book for black Americans and become a guidebook to inspire his fellow people to think about their future.

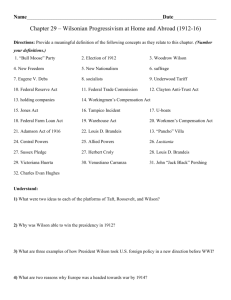

August Wilson wrote The Piano Lesson in 1986, and it opened on Broadway in

1990. Following the similar focus on history with the early plays, it points out the importance of the transmission of black cultural values and inheritance in particular.

Hence, I will use this idea as an example to analyze Wilson’s central notions of black identities via the examination of African American cultural elements distinctively and recurrently used in his dramaturgy. Before we discuss how Wilson thinks of black identities, an overview of the playwright, the play, and the theories applied for the study is necessary.

August Wilson

Since the first successful play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom , opened in 1984,

American playwright August Wilson has attracted the world’s attention to his dramaturgy. In the following years, he received many awards as well as prestige,

1

and it came to a peak when The Piano Lesson won him his second Pulitzer Prize in 1990 after Fences in 1987. Thus he was confirmed as one of the most important contemporary American playwrights.

Born in 1945, Wilson was given a name Freddy August Kittel.

2

Because his mother’s maiden name was Wilson, he later picked it up for his last name. His father,

Frederick Kittel, was a white baker, but most of the time he did not appear in the

1

From 1985 to1996, August Wilson has won five New York Drama Critics’ Awards for Best Play ( Ma

Rainey , Fences , Joe Turner , Piano Lesson , Seven Guitars ), two Drama Desk Awards ( Fences , Piano

Lesson ), one Outer Critics’ Circle Award ( Fences ), six Tony Award nominations ( Ma Rainey , Fences ,

Joe Turner , Piano Lesson , Two Trains , Seven Guitars ), one Tony Award for best play ( Fences ), and two

Pulitzer Prizes for drama ( Fences , Piano Lesson ). He has also received Rockefeller (1984), McKnight

(1985), Guggenheim (1986), and Bush Artists (1993) fellowships in playwriting. Wilson is one of the seven American playwrights to win Pulitzer Prize at least twice (Eugene O’Neill, George S. Kaufman,

Robert E. Sherwood, Thornton Wilder, Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, and August Wilson). See

2

Nadel 1, and Elkins xi, xix-xxii.

For more information about Wilson’s background, see Shafer 5-18.

household. His mother had to work hard to support the whole family with six children.

Wilson lived and grew up in the racially mixed ghetto of Pittsburgh. This environment gave him a great influence upon his writing later. After his natural father died in 1965, his mother remarried David Bedford and the family moved to a white suburb, where

Wilson encountered radical racism in the community and the schools (Shafer 6). Due to his classmates’ discrimination against him, he became involved in so many fights that he had to transfer to several schools in his high school (Shafer 6-7). Though he showed a talent in history, his teacher did not trust him and accused him of plagiarizing a fellow student’s paper on Napoleon (Shafer 7). Eventually, he gave up his formal education and proceeded self-study in a local library. It was here that

Wilson “spent schooldays reading the classics of world literature, newer work of black writers, and books about the life of blacks in America” (Hill 87). He began to take a great interest in writing poetry

3

and short fiction.

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, Wilson particularly “became involved in the Black Power movement” (Nadel 1) through the theatre. In the late

1960s, Wilson and his fellow writer and friend Rob Penny co-founded the Black

Horizons Theatre in Pittsburgh, where he wrote his first one-act play and premiered it.

By way of the theatre, “he participated in the activism of the Black Power movement and became committed to increasing political awareness in his community” (Bloom

11). At that time he began his career as a playwright, but it was not successful in the early years “because of his inability to construct dialogue to his own satisfaction”

(Bigsby 286). In a 1989 interview he told the critic C. W. E. Bigsby why his earlier attempts at writing plays failed: “The reason I couldn’t write dialogue was because I

3

In the library, he read Afro-American literary works by Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Countee

Cullen, and Arna Bontemps, the writers of the Harlem Renaissance. His poetic training in his early life has been reflected in his playwriting. See Galens 244.

didn’t respect the way blacks talked; so I always tried to alter it” (286). In 1978, he moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, a city with few black residents. Apart from his hometown he suddenly “gained a new appreciation of the language he had heard all his life” and “learned to listen to the voices of his past and create dialogue with reality, poetry, and dramatic quality” (Shafer 9). He explained to the interviewer: “for the first time I began to hear the voices I had been brought up with all my life and I realised I didn’t have to change it. I began to respect it” (Bigsby 286).

Wilson kept working on playwriting and submitted his plays to the O’Neill

Playwrights Conference, where he met his future director, mentor, and “surrogate father” (Shafer 11), Lloyd Richards.

4

Finally in 1982 his play Ma Rainey’s Black

Bottom was accepted by the Conference, directed by Richards, and produced at regional theatres.

5

It was not until his 1984 Broadway hit Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom garnered the New York Drama Critics Circle Award that Wilson became famous, being lifted “into the category of major playwright seemingly overnight” (Shafer 11).

In 1987, his next play Fences overwhelmingly won many big awards on playwriting, including his first Pulitzer Prize.

6

Fences was “even required reading in high schools across the country with accompanying study guides” (Elam 361) to further help students get a better understanding of black people in a multicultural society.

Originally, Wilson did not intend to write “a historical circle” until the success of Ma

Rainey’s Black Bottom made him recognize “the logic of his own work” (Bigsby 286).

4

According to Shafer, Wilson and Richards have “moved into a working relationship which has lasted through the years based on Richards’ intuitive response to the plays and Wilson’s trust in his suggestions” (11). Almost all of Wilson’s plays are directed by Richards (Bloom 12). The critic Sandra

G. Shannon analyzes their long-term “director-playwright” collaborative as well as “father-son team”

5

(195) relationships in her article “Subtle Imposition: The Lloyd Richards-August Wilson Formula.”

As the artistic director for the Yale School of Drama, Lloyd Richards helped Wilson revise Ma Rainey and put it to stage at the Yale Repertory Theater in 1984. Since Ma Rainey , each of August Wilson’s plays has begun the process: “a staged reading at the Conference, production at Yale, then ‘production sharing’ at regional theatres throughout the country” (Shafer 11) before opening on Broadway.

6

Fences won the five major awards of that year: the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, the Drama

Desk Award, the Tony, the Pulitzer, and the John Gassner Outer Critics’ Circle award for best American playwright. See Elkins xxi.

By this time Wilson told interviewers that he had a plan of “writing a play about the

African American experience in each decade of the century” (Brockett 630), all of them “dealing with the ‘auto-biography’ of blacks in America” (Shafer 11). Now he has completed eight plays within the historical circle,

7

offering a condensed

“first-hand” Afro-American history from the 1910s to the 1980s (Bloom 12).

August Wilson draws on many black cultural practices and institutions such as

“folk customs and beliefs, music, religion, work, language, food, clothing” (Shannon,

Vision 194) in his play. He uses ‘the blues and storytelling’ (Pereira 12) to express the recurring themes with which he explores his imaginary black world: “the preoccupation with uprootedness,” the characters’ “struggle to define themselves,” and “their African heritage within the context of racism and slavery” (Bloom 13).

Through his special manipulation of black dialogue, music, tradition, and a historical backdrop, August Wilson presents his authentic black experience and history which are different from what the mainstream society records. His plays invite not only white but also black audiences to think over “cultural differences,” which he contends should be treated as “sources of pride rather than as evidence of inferiority” (Shannon,

Vision 194) for black people. He thinks the African Americans should recover dignity by recognition of their cultural values left in the past days.

Plot Summary of The Piano Lesson

The background of The Piano Lesson is set in Pittsburgh in 1936, during the

Great Depression. Central to this play is an old piano that stands upright in the parlor of Doaker Charles’s house. Berniece, in her mid-thirties, and her daughter Maretha

7

With the setting time in the parentheses, they are Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1927), Fences (1957),

Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1911), The Piano Lesson (1936), Two Trains Running (1968), Seven

Guitars (1948), Jitney (1971), and King Hedley II (1985). For more information about Wilson’s plays and other works, see Shannon’s “Annotated Bibliography of Works and about August Wilson.”

live with her uncle Doaker, a 47-year-old railroad cook. The story begins with a hurried and loud knock on the door in the early morning when everybody is still asleep. Boy Willie, Berniece’s brother in his thirties, and his friend Lymon unexpectedly turn up at the house. They set out on a journey from Mississippi in the

South where the Charles family used to live and work as slaves, to Pittsburgh in the

North where widowed Berniece seeks a shelter from a sad memory. Three years ago, her husband Crawley was killed when trying to help Boy Willie steal wood. The goal of the travel for Boy Willie is to claim his own right to the use of “a 135-year-old piano” (Shannon, Vision 144). This abrupt visit breaks the silence of the twilight hour as well as the seeming quietness of Berniece’s three-year peaceful life in Pittsburgh, implying “something akin to a storm” ( PL 1)

8

is set to occur. Although their unwelcome appearance makes Berniece anxious and irritated, these two men bring much needed vigor, passion, and a fresh atmosphere to the coldly hushed house.

With their arrival, they bring with them some information from their hometown in Mississippi. First, the land-owner Sutter, for whom Boy Willie works as an indentured farmer and whose ancestors the Charles family had ever served as slaves in the antebellum period, is found dead falling into a well. The countrymen believe that “the Ghosts of the Yellow Dog” ( PL 4) catch his life. But Berniece believes it is

Boy Willie who murders him. Second, arriving with a truckload of watermelons, Boy

Willie wants to sell them as one part of his fund-raising project to purchase Sutter’s land. In addition to selling fruit, the most important purpose of his visit is to deal with the old family heirloom, the piano. If he sells it, he will collect enough money to make his dream come true. It is his dream to buy land from Sutter’s brother with a reasonably low price, to hire workers to plant cotton for him, and to remove the

8

Hereafter, The Piano Lesson will be abbreviated as “ PL ” in all parenthetical documentation. All quotations are from August Wilson, The Piano Lesson . New York: Plume, 1990.

shamefulness caused by slavery. He hopes finally he will be equally treated as the white people. He knows of some white man who plans to purchase black musical instruments for collection. He thinks he can accomplish his dream if he persuades his sister to sell the piano. When he reveals his plan to his uncle Doaker, Doaker tells him the story of the piano and its relations with the Charles family, whose members were traded for the piano by the owner in the past days. Berniece regards the piano as a reminiscence of her deceased mother Mama Ola, who had mourned over her husband’s death for seventeen years. Aware of Boy Willie’s intention, Berniece blames her father, brother, and husband for making her and her mother cry. At this moment towards the end of Act I, Sutter’s ghost appears and frightens Maretha.

In Act II, Boy Willie encourages Berniece to face herself as a black. He even asks her to teach Maretha to live with black pride and dignity. The conflict between

Boy Willie and Berniece breaks out when Berniece tries to take out her pistol to prevent Boy Willie from moving the piano. But in the meantime, their uncle Wining

Boy, a former pianist in his mid-fifties, drunkenly arrives home. His appearance intervenes the conflict. Finally, when the presence of Sutter’s ghost is felt again, the preacher Avery, who used to court Berniece, begins the exorcism to chase the evil out of the piano. When the Christian exorcising ceremony has failed to drive off the white ghost, Boy Willie goes into a frenzy and rushes upstairs to wrestle with the ghost.

Aware of the immediate danger to her brother, Berniece plays the piano and chants an invocation to arouse ancestral spirits to help her. In the meanwhile the sound of a train approaching is heard. Symbolically the Ghosts of the Yellow Dog defeat the white ghost. After the ghost Sutter is repulsed, Boy Willie finally decides not to sell the piano. Before he returns to the South as the end of the journey, he requires that

Berniece and Maretha should continue to play the piano.

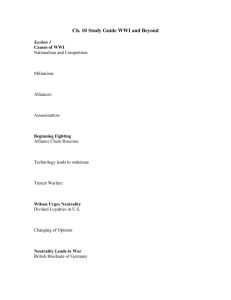

The Historical Background of The Piano Lesson

With regard to the treatment of history, the critic C. W. E. Bigsby contends,

Hansberry, Baldwin, and Baraka are concerned with “making history” while Wilson is

“a recorder of history” (297). While the former three writers may try to exercise the social reforming strategy by dramatizing their political beliefs into the play, Wilson focuses on restoring the reality of history about the blacks. This does not mean, however, that he does not play the role of dramatist. In the case of a “historical dramatist” like August Wilson, the play critic Sandra G. Shannon argues, “history becomes secondary to his or her imagination, which often becomes the dominant force at work” ( Vision 4). Wilson begins with his own experience of growing up in a black community, and then fuses it with the history of African American culture, generating an “imagined reality of the historical milieu” (Shannon, Vision 5) in his dramatic world. History plays a secondary role to the depiction of human beings in turmoil. In short, Wilson does not intend to merely record historical events in a politically correct sense. More importantly, he shows his concern for a reality of black experience in a retrospectively humanist thinking. He examines and then rehabilitates black cultural life from a black perspective without distortion or exaggeration.

The background of The Piano Lesson has much to do with America’s history of slavery.

9

According to David Galens, “[t]he widespread importation of slaves to

America began in the 1690s in Virginia” (252), but the beginning of slavery in

America can be traced back earlier. In an interview with Bigsby, Wilson asserts that black people have “been on the north American continent for three hundred and seventy years” (296). In the early days, the colonizers preferred indentured European servants over more expensive black slaves. When the employment of European

9

The piano is a product of the slavery time and still has its influence to cause a profound familial dispute after decades in the 1930s.

immigrants could not sufficiently meet the need, however, slavery prevailed with a forced migration of enslaved people from Africa to America by ship. These Africans lost their freedom and their offspring to their masters.

Because the reason that “the Revolution’s expression of freedom and equality for all men was contradicted by the existence of an enslaved underclass” (Galens 252), some African descendants were sent back to Liberia to build their country under abolitionist support. With the flourishing development of plantation system in the

South, however, the farm-owners needed more slaves for agricultural labors. In the antebellum period, while “strong opposition to slavery developed in the North,”

“southern slave-owners and apologists for slavery began to offer the public ‘scientific’ and ‘philosophical’ defenses of slavery” (Galens 252). The continuing tension between the abolitionist North and the pro-slavery South led to the American Civil

War (1861-1865). President Abraham Lincoln issued The Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, emancipating slaves in the southern states. Later “congress passed the thirteenth amendment in 1865, thus emancipating all remaining slaves” (Galens

252). Although the action of The Piano Lesson is not set in the slavery period, the story of the play can be traced back to the antebellum period when the members of the

Charles family were still the slaves of the Sutters. Through Doaker’s storytelling ( PL

42-6), we know in the slavery time Boy Willie and Berniece’s great-grandmother

Berniece and her son were traded off by Robert Sutter for the piano. In other words, the story of the play covers a great time span, including at least four generations from the past to the present.

After the Civil War came the Reconstruction era (1865-1876). The nightmares of slavery did not totally vanish with the victory of the North. Due to “a growing wave of conciliatory action and nostalgia sentiments for the South,” the promise of promoting black people’s social position was sacrificed by introducing “the ‘Jim

Crow’ segregation laws that disfranchised blacks and made true civil rights impossible” in the 1880s and 1890s (Galens 252). Though these ex-slaves received less education and fewer opportunities for jobs than white Americans, they still could make a living by hands working on the farms as sharecroppers or by leaving for urban factories. Most people chose to settle in the South, but “in the boom years of the

1910s and 1920s, and during and after World War I (1914-1919) in particular, there was a mass exodus of southern blacks to the northern cities” (Galens 252-53). When time went forward to the 1930s, the Depression undermined America’s economic stability, making it “difficult enough for most Americans but devastating for blacks”

(Pereira 86). It is against this background that The Piano Lesson is set in 1936, when the Great Depression still had a conspicuous effect on society.

Wilson takes advantage of the issue of economic instability in society as well as black migrations from the South to the North to bring out his concern over black identity issues. Because of the gloomy prospect and the sad experience in the South,

Berniece moves to Pittsburgh to live with her uncle Doaker. Because of the economic instability in the 30s, Boy Willie has a chance to buy his former master’s land.

Because of Berniece’s migration to Pittsburgh, Boy Willie takes on a journey to the

North. Finally, because of the economical reason and the dispute over the use of the piano, the protagonists in this play are confronted with the question of identity.

Literary Reviews

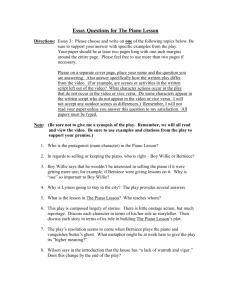

As the fourth play of Wilson’s ten-play project produced on Broadway, The Piano

Lesson continues to depict black experience by applying folklore, music, and spirits to his dramatic work. Though it has won the Drama Desk Award, the New York Drama

Critics’ Circle Award, a Tony nomination, the Outstanding Play Award from American

Theatre Critics, and the Pulitzer Prize (Elkins xxi), it “received more hostile criticism

than any earlier play” (Shafer 37). For example, in New York John Simon complained that it was “an unwieldy mixture of farce, drama, and Broadway musical” (qtd. in

Galens 254). Mimi Kramer in the New Yorker “found the play too long, the ending mystical and melodramatic, and the conclusion unclear” (Shafer 37).

The most negative criticism came with Brustein and Simon’s attack on Wilson’s incompetent and immature technique in dramaturgy. In his article “The Lesson of

‘ The Piano Lesson ’” published in New Republic , Robert Brustein considered The

Piano Lesson “the most poorly composed of Wilson’s four produced works” (28). He found Wilson’s dialogue lacking of power, poetry, and music (28-29) and the performance “too long for its subject matter” (29). He also pointed out the awkwardness of the supernatural element and he felt Wilson was “reaching a dead end in his examination of American racism” (29-30). In his opinion, the appearance of the ghost in a realistic play merely showed the playwright’s incapability to handle his material. As for Wilson’s successful presentation of black experience, he thought it was likely to “stimulate the guilt glands of liberal white audience” by exercising “a perception of victimization” throughout the play (28). In addition to Brustein’s vehement criticism on Wilson’s clumsy technique, Simon’s negative comment centered on its “having many sub-plots,” “mixing genres,” and “being repetitive” (qtd. in Galens 255).

However, most critics affirmed that The Piano Lesson was worthy of appreciation. Clive Barnes in New York Post’s praised it as “the fourth, best, and most immediate in the series of plays exploring the Afro-American experience during this century” (qtd. in Galens 254). Concerning the presence of supernatural elements, on the contrary, Michael Morales in his article “Ghosts on the Piano: August Wilson and the Representation of Black American History” contends that “the interconnection of the mystical and the historical cannot be brushed aside” (112). Whereas other critics

attack the mixing genres of the play,

10

David Galens recognizes Wilson’s dramatic strategy:

Wilson’s mixing of genres is natural for a playwright who seeks to represent dual cultural traditions in one form and on one stage, and his inclusion of a supernatural sub-plot reflects African-American culture in the 1930s, not white American culture in the 1980s. (254)

As an important contemporary American playwright, August Wilson certainly has been frequently interviewed and discussed. Many articles and books have been written to explore the themes of his imaginative world as well as to examine his dramatic skills. After my research on such criticisms, I find black music, or namely the blues, and Wilson’s perspective of history undoubtedly consist of the two major themes that have drawn people’s attention to his dramaturgy.

Music is found a unique but universal component in Wilson’s theatre.

Concerning musical elements utilized in the play, Brian Crow and Chris Banfield in

An Introduction to Post-colonial Theatre attribute the power of the blues to “the forces by which cultural emancipation and empowerment may be achieved” (60).

They believe music in Wilson’s theatre functions as “summoning mysterious powers of recovery and reintegration” (57) for it brings one to connect with the cultural past.

By way of connecting music with the discourse of history in terms of its narrative function, theatre critic Jay Plum in “Blues, History, and the Dramaturgy of August

Wilson” considers the blues as “an empowering text that records African American experiences” (564). Similarly, in “August Wilson’s Burden: The Function of

Neoclassical Jazz,” Craig Werner shares the same idea of music’s functionality with

Plum, contending “black music encodes memories of historical events and personal

10

William A. Henry III argued that “Wilson had blurred genre boundaries by mixing tales of the supernatural with ‘kitchen-sink realism.’” See Galens 254.

experiences omitted from or distorted by the written documentation of European

American cultural memory” (26). Keith Clark in Black Manhood in James Baldwin,

Ernest J. Gaines, and August Wilson brings up the importance of music’s role in

Wilson’s plays. Analyzing the black subjectivity in terms of male characters and communities, he indicates “the centering of black music stands as his most striking modal departure from his white dramatic predecessors” (96). In general, the investigation of the significance of black music becomes an imperative research work for those who are interested in Wilson’s drama, including The Piano Lesson . Actually the playwright has admitted that the blues constitutes the most influential element on his creative writing.

11

Besides black music, history is another aspect through which Wilson has spent time and energies restructuring his imagined black world. Because of his endeavors to complete a ten-play historical cycle that aims to represent an authentic black experience in the twentieth century, scholars particularly feel interested in Wilson’s idea about history. For Wilson, in C. W. E. Bigsby’s words to encapsulate his view of history, “[t]he past is the present” (286). The past provides itself as a retrospection and abundance of cultural values for people in the present to define themselves. In The

Dramatic Vision of August Wilson Sandra G. Shannon suggests that “ The Piano

Lesson thus becomes the playwright’s self-authored textbook of culture and history, instructing playgoers about the black experience in America” (147). She asserts that it is not only the characters in the play, who find “their cultural past” (163), but also the playwright and the audience, who find a space to examine their cultural identity

11

August Wilson has once mentioned what casts an effect on his writing: “In terms of influence on my work, I have what I call my four B’s: Romare Bearden; Imamu Amiri Baraka, the writer; Jorge Luis

Borges, the Argentine short-story writer; and the biggest B of all: the blues” (qtd. in Rocha 3). Romare

Bearden is both a musician and a collagist, whose paintings in a modern and African American fashion offer Wilson an inspiring insight into his dramatic landscape. The Piano Lesson and Joe Turner’s Come and Gone are the two plays directly inspired by his collages. For more information about the ‘four B’s,’ see Mark William Rocha’s “August Wilson and the Four B’s Influences” and Joan Fishman’s “Romare

Bearden, August Wilson, and the Traditions of African Performance.”

through the lesson of the piano incident. Michael Morales in “Ghosts on the Piano:

August Wilson and the Representation of Black American History” contends that the task Wilson shares with the other African American writers is “a simultaneously reactive/reconstructive engagement with the representation of blacks and the representation of history by the dominant culture” (105).

Despite the fact that music and history are common themes in all of Wilson’s plays, there is still another space for scholarly research. Kim Pereira’s book, August

Wilson and the African-American Odyssey , bases its analysis on the recurring ideas of

“separation, migration, and reunion” (2) and brings the idea of journey into the greater discussion of Wilson’s works. The most recently published essay on The Piano Lesson is Harry J. Elam, Jr.’s “The Dialectics of August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson .” Elam approaches the play from a dialectical perspective that explicates “[t]he argument between brother and sister plays out as a dialectical debate for which the audience must construct a synthesis” (362). Elam’s words implicitly touch upon the social function of theatre when dealing with the relationship among the playwright, the characters, and the audience. Moreover, he relates The Piano Lesson to Lorraine

Hansberry’s masterpiece A Raisin in the Sun (1959) and makes a comparative analysis of these two plays by using Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s critical term ‘signifyin(g).’

12

From this point of analysis, he argues that the former is a “signifyin(g) revision” (367) of the latter. Although such criticisms facilitate a general understanding of Wilson’s

12

Henry Louis Gates Jr. introduces this term ‘signifyin(g)’ in his book The Signifying Monkey . A concise definition of it can be found in Joseph Childers and Gary Hentzi’s The Columbia Dictionary of

Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism : Based upon a “sociolinguistic analysis, signifyin(g) in Gates’s formulation names an African-American ‘trope of tropes,’ a metafigure denoting all rhetorical strategies that subvert the dominant meaning of language practices through forms of linguistic free play.

Functioning by means of indirection, implication, and metaphorical reasoning, signifyin(g) subsumes the many vernacular forms of African-American culture, including ‘marking, loud-talking, testifying, calling out (of one’s name), sounding, rapping, [and] playing the dozens” (279). In Harry J. Elam, Jr.’s analysis of these two plays, for instance, we can comprehend a parallel relationship between the male protagonists Boy Willie and Walter Lee Younger and the female protagonists Berniece and Mama

Younger in terms of the signifyin(g) effect. For more discussion on signifyin(g) effect and the comparison, please see Elam 363-67.

drama, there is something more to be done in order to envision his aspiration to better understand black people and black culture.

The Argument

Among the critical works on August Wilson’s ambition to handle African

American materials in The Piano Lesson , several concepts—history, music, migration, spirits, and identity—have often been discussed as indispensable ingredients to survey the playwright’s narrative style and purpose. While reading each of his plays, most critics choose two or three of these items to examine Wilson’s presentation of black living experience;

13

however, they only treat these recurring issues separately and functionally, not coherently and contextually. For example, critics frequently examine the function of the blues and the meaning of history as themes in all of Wilson’s plays.

But they are seldom framed by an overarching central motif that organizes the isolated themes. Consequently I cannot see a comprehensive perspective that integrates these themes to grasp Wilson’s concern hidden in the words.

As for the non-traditional genre mingled with black music, ghosts and spirits, and folktales, my argument is that they facilitate our reading of black culture because they help construct a realistic landscape. The combination of African American elements has become a part of Wilson’s distinctive creative style. Nevertheless, many important themes and directions revealed in the play beg the question of how one should employ and integrate them to illuminate the literary and social meaning that

13

As I have mentioned in Literary Reviews, for instance, Kim Pereira in August Wilson and the

African-American Odyssey seizes specific terms and issues in the play—the function of the blues, black people’s migration, selling the piano, and the appearance of the ghost—to discuss how The Piano

Lesson provides “a new direction in the odyssey of African Americans in the twentieth century” (103).

While she strives to demonstrate the importance of those mentioned above with a textual study, I do not see a consistent and holistic vision of black experience in terms of the themes she has rendered. In brief, the four themes neither correlate to one another nor are framed by an underlying, central motif that centers on the problem of black cultural identity, to which I think we should pay much attention in

Wilson’s plays.

August Wilson embeds into the play. In an interview with Bigsby, Wilson shows his concern for the difficulties confronting black people:

As a whole our generation knows very little about our past… My parents’ generation tried to shield their children from the indignities they suffered… I think it’s largely a question of identity. Without knowing your past, you don’t know your present—and you certainly can’t plot your future… You go out and discover it for yourself. (293)

Since what the playwright cares for is “a question of identity,” we should begin with examining his idea of black identity by way of his play. In this essay, I would like to discuss the degree to which August Wilson successfully reconstructs a new black identity, which is different from the old stigmatized one. I will center my analysis on three prominent aspects that are closely connected with the identity issue in the play: the migration, the ghost on the piano, and the black music.

My first concern is the quest for black diasporic identity. Both the concept of migration and the search for the American dream have significant roles in the play.

14

It is frequently seen that the characters wander everywhere only to seek a better life.

Boy Willie travels to the North with his dream of becoming a land-owner. Doaker as a railroad cook has to move from place to place with the train. After emancipation, though black Americans are free to move, they have lost both a geographical and a communal linkage to Africa, their motherland. In the case of the characters in The

Piano Lesson , where should they go to find their home? In the South of the USA or in

Africa? By exploring black diasporic identity, we will understand more about the mobility and instability of the black subject’s nature.

14

All of the characters in The Piano Lesson have had or suffered from the experiences of migrating from one place to another place, particularly from the South to the North, in search of a dream which I call the American dream. For example, Boy Willie’s friend Lymon drives a truck with him from their hometown Mississippi to Pittsburgh for seeking a job, a wife, and a home. I will discuss the issue of the black people’s American dream in terms of diasporic identity in Chapter Two.

My second concern is the emergence and effect of racial identity along with the encounter of the past in the present. With Boy Willie’s journey to the North, Sutter’s ghost turns up to claim its right to the ownership of the piano. His occurrence brings about the conflict of the position between the self and the other, namely the white and the black. When the piano undermines the past history, the protagonists have to face their racial selves, which lead to their subsequent identity crises. I think the analysis of the arrangement of the white ghost challenges the protagonists’ racial identity, which makes it easier for the readers to comprehend the marginal position of the black subject in postmodern society.

The relationship between black music and cultural identity is my third concern.

Like Wilson’s other plays, the characters often sing songs and play black music, such as the blues ensemble. This is especially true at the end of The Piano Lesson when

Berniece determines to play the piano and chant an invocation to her ancestors for help. Here I am interested in the power of black music as well as its cultural function in connecting the individual and the collective. I will discuss in the thesis how the blues shapes and demonstrates black identity. After the investigation of this musicalized identity, it will be manifest to show the communicability and connectivity of the black subject through playing music.

Theoretical Framework

As the fourth addition to the ten-play historical circle, The Piano Lesson continues with Wilson’s ambition to explore, structure, and locate a black subject in a white dominant society. He looks passionately at “the margin,” or the black experience in America that cannot be found “from the history book” (Bigsby 287).

Thus, he tries to illuminate this marginalized African American history by positioning

“African Americans as the subjects of his plays” (Plum 562). As the black subject is

the concern of Wilson’s play, I will examine Wilson’s display of the black subject by discussing black diasporic, racial, and musicalized identities. I will apply Paul

Gilroy’s assertion of the Black Atlantic with regard to the dimensions of diaspora, slavery, and music, Stuart Hall’s notion of cultural identity and diaspora, Michel

Foucault’s counter-memory and the concept of history, and Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial theory to the reading of The Piano Lesson . The main body of my thesis will be divided into three parts, each of which will scrutinize the black subject from its respective analysis of the diasporic, racial, and musicalized nature of black existence. Finally I will conclude my thesis with a demonstration of how August

Wilson creates a new black subject through reconstruction of black identities in The

Piano Lesson .

Given the notion that The Piano Lesson is about the black subject’s quest for identity, Paul Gilroy’s concept of the Black Atlantic greatly facilitates my understanding of the complex condition of modern and postmodern black identity. His book, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness , is an insightful reference and will serve as a theoretical basis for my thesis. As a British sociologist and cultural theorist, Gilroy tries to depict black culture from a more holistic, cross-boundary perspective than the monolithic, nation-oriented outlook on race as a biological distinction. In contrast to ethnic absolutism or cultural nationalism, Gilroy’s argument emphasizes “the intercultural and transnational formation” (ix) of the black culture across the Atlantic Ocean. He regards the image of ‘the Black Atlantic’ as a preliminary framework for further discussing the cultural connection between black people of the New World and the Old World. He bases his ideas upon the trend of the globalization of cultures and identities and offers a definition of the subject of this book:

The specificity of the modern political and cultural formation I want to

call the black Atlantic can be defined, on the one level, through this

desire to transcend both the structures of the nation state and the

constraints of ethnicity and national particularity. These desires are

relevant to understanding political organising and cultural criticism.

They have always sat uneasily alongside the strategic choices forced on

black movements and individuals embedded in national political cultures

and nation states in America, the Caribbean, and Europe. (19)

Establishing his theory upon the works and the arguments of black writers such as

W.E.B. Du Bois, Richard Wright, Martin Delany, and Frederic Douglass for textual and theoretical supplements, Gilroy examines the relationship between modernity and the Black Atlantic, whose goal is to show people, the experiences of black people were parts of the abstract modernity they found so puzzling and to produce as evidence some of the things that black intellectuals had said—sometimes as defenders of the West, sometimes as its sharpest critics—about their sense of embeddedness in the modern world. (ix)

Gilroy uses Du Bois’s critical term ‘double consciousness’—“to be both

European and black” (1)—in conjunction with a transnational study of black culture to challenge the “obsessions with racial purity which are circulating inside and outside black politics” (xi). Through the exploration of the historical migrations, exchanges, discontinuities of the diaspora culture, he attempts to reaffirm the notion of the modern world as a cultural hybrid with “the instability and mutability of identities which are always unfinished, always being remade” (xi). Aside from the arguments of

Du Bois and Wright, the central themes he attributes to forming or displaying black modernity in The Black Atlantic are diaspora, slavery, and particularly the black music, three of which play significant roles in the making of black history. Later I will bring

his explanation of these three essential aspects, which are relevant to the shaping of the black culture, into my examination of black diasporic, racial, and musicalized identities.

The image of migration finds a historical meaning in the black history during the period in which the Africans were shipped across the Middle Passage to the New

World. Today, black people’s migrations take place primarily across the American continent and are motivated by economic or social reasons, not by the threat of mortal force as in the past. In order to examine the migrating nature of the black existence,

Paul Gilroy’s concept of diaspora and Stuart Hall’s delineation of cultural identity and diaspora can help us obtain a clear outline of it. According to Gilroy, the term diaspora refers to “a network of people, scattered in a process of non-voluntary displacement, usually created by violence or under threat of violence or death”

(“Diaspora” 328). He applies the concept of diaspora in terms of the sameness of miserable experiences—kidnapped, shipped, enslaved, labored, and oppressed by the white masters—and of cultural inheritances from Africa

15

to the discussion of postmodern black identities. This “diaspora consciousness” (318) that is produced by that shared experience helps black people share with one another the diasporic identity of the Black Atlantic which transcends geographical origins or bonds of kinship.

British cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s explication of identity can serve as a complement to the study of the mobility of black nature. In “Cultural Identity and

Diaspora,” he examines the questions of representation and cultural identity of black people, and then leads to the debate over diasopra issues. First, he asserts that we should pay much attention to the analysis of identity—identity is not a fixed thing, but

15

Music is one of the most important cultural inheritances from Africa. Many forms of musical expressions such as the blues, jazz, rap, and hip-pop are played and celebrated by individuals and communities of the black culture. For the discussion of black music and identity, see Chapter Four.

should be seen as “an on-going process” (“Question” 287). Second, he poses two ways of thinking about cultural identity. One is based upon a shared experience, that is to say, a collective memory. This gives people a common cultural identity in which they may be called “one people” (223). The other is seen from the viewpoint of

“difference” (225), which draws our attention to the distinctness of individuals.

Consequently, with these two different ideas towards black diasporic identity, Hall contends that people of the African diaspora are those who are “constantly producing and reproducing themselves anew, through transformation and difference” (235). That is to say, their identities are hybridized through the process of the diaspora experience.

For them the “original ‘Africa’ is no longer there” because Africa “has been transformed” (231). The characters in The Piano Lesson seem accustomed to wandering or traveling, and eagerly try to find their home. This is evident at the end of the play, when Boy Willie decides to return to his hometown in the South to settle down. Hence, I would like to employ Gilroy’s and Hall’s theories about diaspora to investigate ‘the concept of home’ of the characters as well as the nature of their migrations.

Based on the notion that white terror, or the system of slavery has its significance in the western civilization and modernity of the Black Atlantic, Paul Gilroy’s examination of racial slavery in The Black Atlantic helps to see the relationship between slave-owners and slaves. Looking into the legacy of the Enlightenment, he inspects the thinking of “the first great wave of writers and thinkers about modernity”

(qtd. in Atlantic 46), especially that of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic. In Hegel’s allegory, the slave finally refuses death but submits to the slave-owner because of the

“mortal terror of his sovereign master” and the continuing “trial by death” (qtd. in

Atlantic 55). Gilroy utilizes the stories of Frederic Douglass and Margaret Garner,

16 in which they prefer death to enslavement, as evidence to invert Hegel’s slave narrative. He emphasizes the modernity of the black subject as contradictory to western rationalism and “constructs a conception of the slave subject as an agent”

(68). Gilroy’s idea, when applied to the reading of The Piano Lesson , is exemplified by Boy Willie’s courage for fighting with the white ghost and his father’s unflinching bravery to take away the piano from the Sutter family.

The piano in the play is a gate to the past memory and history of the descendants of black slaves. Through different reactions to the piano, the protagonists intend to re-examine their history and give it an authentic meaning. Here, Michel Foucault’s concept of history and counter-memory is useful to study Wilson’s view of history. In

Foucault’s central idea, history is fragmented, flowing, and discontinuous. His viewpoint towards the nature of history is the opposite of the traditional perspective that emphasizes the continuity of historical events. In Language, Counter-Memory,

Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews , he brings up an ideal term named “effective history” (154), whose essence is different from that of official history which represents the voice of the authority. He thinks only ‘effective history’ can convey the voice of otherness. This concept appropriately supports Wilson’s insistence on his expression of the marginalized black experience, which is described in his historical project. Writing black experience for Wilson can be seen as a “counter-memory”

(Foucault 160) to the orthodox history. I will employ this idea to examine Wilson’s argument for establishing his chronically contrived historical cycle.

As for the white ghost, in spite of its supernatural appearance in the realistic setting, it has recast a vast shadow on the survivors of slavery since emancipation.

16

For more information about the stories of these two persons, please see Chapter Three, pp. 74-

75.

The ghost evokes black terror of the white and anxiety about self-consciousness.

Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial theory in Black Skin, White Masks can be properly used to analyze the repressed racial identities of the characters facing the oppression from the haunting memory. Based upon a psychoanalytical viewpoint, in Fanon’s book, he states the black self is “fixed” by the gaze of the other, and was born “an object in the midst of other objects” (109). In other words, the existential nature of the black self has been shaped from the eyes of the white, through the recognition of the other. It is only from the perspective of the other, the white, that the black self has been informed of his difference, his perceived inferiority to the dominant other. Because his skin color becomes the most obvious feature of the body, the “consciousness of the body” spontaneously produces a “negating activity” (110) to depreciate the values of the black. His racial identity is thus formed as “savages, brutes, illiterate” along with

“shame” and “self-contempt” (116-17). As Fanon painfully describes the black as an object, Wilson recounts how the slave ancestors of the characters in The Piano Lesson were traded for goods, for the piano, by white masters. On the other hand, the debate over the piano causes identity crises among the protagonists and brings them into a struggle with what Fanon calls “the fact of blackness” (109). The conflict between

Boy Willie and Berniece will provide Fanon’s postcolonial analysis of blackness an opportunity to show us the reasons why the two siblings confront each other in so contrary a manner.

The blues is the production of the shared black experience in America. Though music has been performed for its recreational purpose, black music or the blues is endowed with social and cultural functions in Wilson’s plays. Paul Gilroy’s analysis of black music in The Black Atlantic helps explain the importance of the blues in black culture. For Paul Gilroy, black music has much to do with the politics of racial authenticity. In his argument, he contends, “the self-identity, political culture, and

grounded aesthetics that distinguish black communities have often been constructed through their music” (102). Through music and “its rituals” (102), the performer of the music and the crowd can build a connective relationship with each other regardless of time and space; one’s identity will go through a process of transformation, exchange, and development in the blues playing. In this manner, music becomes a “model whereby identity can be understood neither as a fixed essence nor as a vague and utterly contingent construction” (102). It is with the musical function called “the blues aesthetic” (Jackson 51) that black music acquires its communicative capability to demonstrate the subject position of blacks, solicit for solidarity in the collective memory, and foster a new black identity. Most importantly,

Gilroy suggests the power of music makes black musical expression “a distinctive counterculture of modernity” (36), which forms his central argument in The Black

Atlantic . Furthermore, I would also like to utilize LeRoi Jones’s (Imamu Amiri

Baraka’s) critiques on history of the blues and Simon Frith’s cultural theory of music and identity to supplement my discussion.

In Chapter Two I will apply Stuart Hall’s study of cultural identity and diaspora, and Paul Gilroy’s idea of diaspora to the examination of black diasporic identity. In

Chapter Three my discussion of black racial identity as well as Wilson’s historical project will benefit from Michel Foucault’s concept of history and counter-memory,

Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial reading of blackness, and Gilroy’s analysis of slavery in terms of modernity. In Chapter Four I will use the elaboration on the blues history from LeRoi Jones and on the function of black music from Gilroy to discuss the relationship between the blues and black identity. Chapter Five is the conclusion of my thesis. Through the exploration of the old and new black identities, it will be helpful to see the formation of a black subject in August Wilson’s dramatic vision.

The old black identity is a repressed, stigmatized, and marginalized one given by

the dominant white society. Due to the old identity, black people lose confidence, encounter an identity crisis, and even refuse to respect their own culture. Now Wilson in The Piano Lesson deconstructs that kind of black history by writing black experience. By writing Boy Willie’s fighting with the ghost, Berniece’s invocation through music, Boy Willie’s final decision to return home, and what is more important, their faithful recognition of the past culture, Wilson lets the characters find their subject positions in the world. He reconstructs new identities for the real black people.

In an interview he reveals his expectation for black people: “if black folks would recognize themselves as Africans and not be afraid to respond to the world as Africans, then they could make their contribution to the world as Africans” (qtd. in Bigsby 293).

This is precisely a part of black identity Wilson strives to construct in his plays.