Developing the Spoken Language Skills of Reception Class

advertisement

BERA

Developing the Spoken Language Skills of Reception Class Children in Two Multicultural,

Inner-City Primary Schools

Author(s): Jeni Riley, Andrew Burrell, Bet McCallum

Source: British Educational Research Journal, Vol. 30, No. 5, Early Years Education (Oct.,

2004), pp. 657-672

Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of BERA

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1502098 .

Accessed: 28/09/2011 09:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd. and BERA are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

British Educational Research Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

BritishEducationalResearchJournal

Vol. 30, No. 5, October2004

CarfaxPublishing

&Francis

Taylor

Group

Developing the spoken language skills

of reception class children in two

multicultural, inner-city primary

schools

Jeni Riley*, Andrew Burrell and Bet McCallum

Universityof London, UK

This article describes a small-scale study which emanated from the concern of the head teachers

and staff of two primary schools serving deprived, multicultural areas of an inner city. The concern

of the staff related to the level of their pupils' spoken language skills through the schools and the

perceived impact that this has on pupils learning more widely. The article explores the nature and

importance of oral language development in the early years and describes an intervention designed

to enhance the spoken language skills of the reception children. The pre-intervention scores of the

children at school entry indicated that the language skills of the children were less well developed

than those of the general population. The findings suggest that the intervention had a positive effect

on the speaking and listening skills of the reception children and that the teachers' involvement in

the research contributed to their professional development.

Introduction

In many countries, including the UK, there has been increasing concern about the

level of oral language competence with which children enter school (Chaney, 1994;

Whitehurst, 1997; Locke et al., 2002). A recent survey carried out in Wales and

undertaken by the Government's Basic Skills Agency (2003) found that two-thirds of

teachers questioned believed that the speaking and listening skills of children on entry

to early education had deteriorated in the past five years. According to the survey, half

of the five-year-olds starting school lack the speaking and listening skills required to

cope in the classroom. Furthermore, findings from a small-scale survey of head

teachers' perceptions regarding children's levels of language competence strongly

suggest that professionals are concerned that children are entering school with poor

*Corresponding author. Institute of Education, University of London, 20 Bedford Way, London,

WC1H 0AL, UK. Email: j.riley@ioe.ac.uk

ISSN 0141-1926 (print)/ISSN 1469-3518 (online)/04/050657-16

@ 2004 British Educational Research Association

DOI: 10.1080/0141192042000234638

658 J. Riley et al.

speaking and listening skills (National LiteracyTrust, 2001). The Chief Inspector of

Schools, David Bell, has also expressed concern about children starting school less

well prepared and lacking in verbal skills. The concern arises from awareness that

children experiencing difficulties will find the demands of school challenging both

academicallyand socially (see, for example, Dockrell et al., in press).

Language and learning

The importance for individuals to possess well-developed spoken language skills is

well documented (Wells, 1987). Success in the educational system and language

competence is positively correlated.Government documentation states that, 'Pupils'

use of language is a vital skill which influences their progress in every area of the

curriculum' (School Curriculumand Assessment Authority [SCAA], 1997, p. 2). It

would seem, therefore, that fluency, competence in and comprehension of spoken

language are the keys to being able to learn effectively. Associated with this is that

there is also a close relationship between the development of language and the

development of thought (Vygotsky, 1986). Language enables communication;

through language the individual can represent feelings, beliefs, desires and knowledge. The relationship between the ability to express oneself and the ability to

integrate socially and to establish and maintain personal relationships is clear

(Leonard, 1997). The result of having language difficultiesis that the children have

problems in three areas: accessing the curriculum on language-related tasks,

interaction and social skills, and attention span and approaches to learning

(Dockrell & Lindsay, 2001).

Speaking and listening in the primary school curriculumAll lessons in the primary

school include, and largely depend on, oral communication. For example, the

teacher's role in explaining, questioning, describing, organizing and evaluating in

the classroom is mostly conducted through talk' (SCAA, 1997 p.6).

Speaking and listening is one key area of the National Curriculum for English

(Department of Education and Science [DES], 1990). However, it receives little

attention within the National Literacy Strategy (NLS) (Department for Education

and Employment [DfEE], 1998), which was introduced into English primaryschools

in 1998. This strategyhas sought to bring about widespreadchanges in the teaching of

literacy in primary schools. Although it is possible to identify areas where speaking

and listening skills are promoted, the frameworkdoes not list specific objectives for

these skills. Within the NLS (DfEE, 1998), speaking and listening take on a

functional quality, as they are perceived as a means by which literacy skills can be

enhanced. The NLS (DfEE, 1998) may have unintentionally inhibited, through

relatively less emphasis, the development of children's oral skills.

Relationship between spoken language and literacyThere is a close relationship

between children's oral language skills and their ability to use written language

Developing spoken language skills 659

effectively to serve their own purposes, particularlyin writing (Lindsay & Dockrell,

2002). Not only are there benefits in developing oracy but because spoken and

written language are interdependent, the development of literacy will also be

enhanced. Goodman and Goodman write, 'Written language development draws

on competence in oral language, since, for most learners, oral language competence

reaches a higher level earlier. As children become literate, the two systems become

interactive, and children use each to support the other when they need to' (1979,

p. 150). Recent research evidence supports this view. Catts and Kamhi (1999)

suggest that delayed language development can adversely affect the acquisition of

written language. The development of comprehension reading skills as children

move beyond the earliest stages of reading is dependent on the strength of their

grammatical and semantic language competence. It would appear that children

with poor skills of language processing are weak at the literal and inferential

comprehension of texts and this holds them back as they reach upper primary

school.

Language, literacy and children for whom English is an additional languageAnother

manifestation of the same issue is that levels of overall English language

competence depress the functioning of populations of children for whom English is

an additional language. At Key Stage 1 (KS1), bilingual children attain scores at

around the national average at aged 7 years, but by 11 years old at Key Stage 2

(KS2) their scores plummet (Kotler et al., 2001). Explanations vary but the most

plausible is the one mentioned above, that in the early stages of reading, children

can be effectively taught to be competent decoders. However, 'higher order'

comprehension skills require the kind of reflection, understanding and reasoning

that needs to be supported by well-developed oral language competence (Sticht &

James, 1984; Geva, 1997). Ironically, the NLS (DfEE, 1998), implemented to

raise literacy standards, with its great emphasis on whole-class and group teaching

does little to promote the development of spoken language skills.

Some researchers,however, argue that children speaking English as an additional

language (EAL) are not seriouslydisadvantaged.For example, Gregoryand Williams

(2000) highlight the wealth of literacypractices in the lives of those often considered

'deprived' of literacy. They argue that 'access to contrastingliteraciesgives children

strength, not weakness;that our childrenhave a treasuretrove upon which to draw as

they go about understandingthe literacy demands of the school' (2000, p. 203).

Language skills and deprivationIt is now accepted that there are differences in the

levels and types of language use between cultures and across the range of socioeconomic backgrounds. There is convincing evidence that children reared in

poverty tend to have poorer spoken language skills than children brought up in

more favourable circumstances (Locke et al., 2002). Hart and Risley (1995) found

great diversity in the quantity of language addressed to children from different

socio-economic backgrounds in the first two and half years of life. Children from

660 J. Riley et al.

professional families received approximatelyfour times the number of interactions

compared with those children living in families on welfare benefit. The nature and

quality of the language input is also important (Pearson et al., 1997). Links made

between disadvantage and school failure (Whitehurst, 1997) also have suggested

that lower levels of spoken language competence at pre-school begin the cycle of

underachievement (Peers & Locke, 1999; Locke & Peers, 2000).

Language skills and genderIn addition to social class differences, there are also

gender differences in language performance. Girls appear to develop verbal abilities

earlier than boys (Resnick & Goldfield, 1992) and learn to read earlier than boys

(Halpern, 1992). It can be speculated that the less impressive performance of boys

in English Standard Assessment Tasks (SATs) at the end of KS1 and KS2 is, at

least, contributed to by their relative underperformance in spoken language on

entry to school and before.

Research design

The head teachers and staff in two primaryschools serving deprived, multicultural

areas of an inner city were concerned about the level of their pupils' spoken language

skills throughout the whole school and the perceived impact this has on pupils'

learning more widely. This small-scale project was funded by the two reception

teachers receiving DfES Best Practice Research Scholarships (BPRS) of ?5000 in

total. The BPRS aim to support classroom-based research in partnership with a

nominated higher education institution (which in this case was the Institute of

Education, London). The present study took the form of an interventionand entailed

the recruitmentof the closest neighbourhood school to provide a comparison.

The project addressed the following research questions:

1. Are the spoken language skills of the reception children at school entry depressed

in comparison with the general population in the two intervention and the one

comparison school?

2. What is the pattern of the children's language development across the various

language skills and in which skills are these children experiencing difficulties?

3. Is it possible to enhance the languagedevelopment of the reception childrenin the

two intervention schools through a teacher-led enrichment programme?

Participants

In the present study we focused on the classes of reception pupils (41 children) in the

two intervention schools, Windsmoor Primary School and Copeland Primary School,

along with one class of reception pupils (10 children) in a comparison school,

Vintners Primary School. Pseudonyms have been used for the three schools The three

schools were situated within half a mile of each other in an inner-city area of high

Developing spoken language skills 661

social and economic deprivation(as indicated by all of the pupils being entitled to free

school meals) and which served a multiculturalpopulation living in council-owned

accommodation. Two-thirds of the pupils had EAL. Parental consent was obtained

for the childrento participate.One child in the comparisonschool was referredfor the

language delay to the educational psychology service during the study but was not

excluded from it as his mother did not manage to attend any of the arranged

appointments at the speech therapy clinic.

Method

Pre- and post-testsToassess the children's spoken language skills and in order to

compare them with the general population, the Clinical Evaluation of Language

Fundamentals (CELF) Assessment Preschool UK (Wiig et al., 1998) was used. All

the reception children in the two intervention schools and the one comparison

school were assessed within three weeks of school entry in September 2002 and

retested in July 2003 on the CELF-Preschool assessment.

The CELF-Preschool assessment is designed to providemeasuresof both receptive

and expressive language skills in the areas of phonology, syntax, semantics and

memory, and word finding and retrieval. The test aims (1) to assist in the

identification of children with language disabilities, (2) to provide a differential

diagnosis of the areas of weakness, and (3) to identify areasfor follow up for language

intervention. The test is designed for use with children aged from three to six years.

Raw scores were used for the purposes of both diagnosis and to measure progress.

The test assesses a range of receptive language and expressive language skillsreceptive language refers to what is heard or understood and expressive language

refers to what is said or articulated.The results of the CELF-Preschool assessment

enabled the teachersto targetspecific areasof languageperformancefor attention and

support.

The six subtests were administeredto each pupil; three assess receptive language

and three assess expressive language. The subtests are:

Receptivelanguage.The following three subtests evaluate receptive language:

1. Linguistic concepts. This subtest evaluates a child's ability to comprehend

directions that:

"*contain early acquired linguistic concepts such as 'either ... or' and 'not';

"*involve quantifiersand ordinals such as 'some' and 'first';

"*increase in length from one- to three-level commands.

2. Basic concepts. This subtest assesses a child's knowledge of modifiers. It can be

used to evaluate a child's ability to interpret one-level oral directions that contain

references to:

* attributes (e.g. understanding of 'cold', 'dry', 'alone', hard');

* dimension/size;

* direction/locality/position;

662 J. Rileyet al.

"*number/quantity;

"*equality(e.g. understanding'same'and 'different').

3. Sentence structure.This subtest evaluates comprehensionof early-acquired

sentenceformationrules.It evaluatesa child'sabilityto comprehendandrespond

to spokensentencesthatincreasein lengthand structuralcomplexity.

language.The followingthreesubtestsevaluateexpressivelanguage:

Expressive

4. Recallingsentencesin context. This subtest evaluatesrecall and repetitionof

spokensentences.It is in the formof a storyandchildrenarerequiredto recalland

repeatlines fromthe story.As the storyprogresses,the numberof morphemes,

syntacticcomplexityandnumberof prepositionsin eachitem increase.

5. Formulatinglabels.This subtestexaminesa child'sabilityto namepicturesthat

wordknowledge/naming).

representnouns andverbs(referential

6. Word structure.This subtest evaluatesa child's knowledgeand use of earlyrulesand forms.

acquiredmorphological

awarenessof teachers,support staff and parent/

The intervention

programmeThe

volunteerhelperswas raisedand their capacityand expertisedevelopedregarding

the most effective ways of supportingspoken languagedevelopmentof pupils

withina receptionclassroomprogrammeof teaching.

An enrichmentlanguageprogramme

wasdesignedconsistingof effectiveandactive

learningexperiencesand targetedteachingfor the receptionchildrenin orderto

facilitateboth their comprehensionand use of spokenlanguage.The enrichment

programmewasdevelopedalongsidesupportedstaffstudyandreadingof the relevant

backgroundliteraturecoupled with advice and support from the Institute of

Education.The projectalso incorporatedthe systematicsharingof good practice

acrossthe wholeof the interventionprimaryschools.

The enrichmentprogrammeinterventions

tookplacewithsmallgroupsof children

andwereledbyvolunteers.The volunteerswereparentsof childrenin thetwo schools

or adultswho enjoyedworkingwithyoungchildrenandwereinterestedin supporting

their learning.None of the volunteershad a formalteachingqualification.The

teacher-designedprogrammeused purposeful,concrete,motivatingactivitiesthat

stimulateda wideuse of languagein a developmentally

appropriate

wayforreception

children.They werebasedon a themeor topic (e.g. toys) and weresupportedby a

rangeof activitiesand resourcesincludingvisits.Eachtopic was taughtin one-hour

sessions per week over a period of 12 weeks at a time. The 12-week topics sometimes

spread over two half-termswith a vacation in the middle. Particularfocus was placed

on vocabularydevelopment, recounting or describing a situation through the use of

narrative language and involving the use of different tenses. The volunteers were

trained before each preparedsession with the children. Evaluationand feedback was

systematicallydone after each taught session.

Developing spoken language skills 663

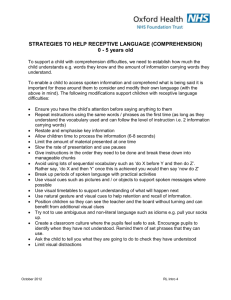

Activity. The CarPark Languagefunction Language structures

Childrenarrangetrees Following

First, parkthe red car,

and houses arounda

instructions

second, parkthe blue

car parkplaymat.

car...

Parkthe red car...

Adult places five small

next to / between /

cars of different

beside /behind/ in

colours aroundthe

frontof anothercar.

mat.

Vocabulary

First, second,

third,fourth,

fifth

Next to,

between, beside,

behind, in front

Figure 1. A typicalactivityused in the interventionwhichwas designedto developordinalnumber

conceptsand languageuse

The following features of classroom interaction, identified as important by Kotler

et al. (2001) in their study, formed an integral part of our intervention:

"*opportunities for extended talk;

"*situations which require collaborative talk;

"*ground rules for task-oriented talk, e.g. waiting and turn-taking;

"*support, guidance and encouragement but not dominance by the adult/teacher;

"*contexts which build on prior experience and enable new learning to occur.

For each activity, the adults working with the children were asked to consider not only

what they were going to do, but also the desired vocabulary use of the children, the

language structures required and the overall function or area of language they were

working in. Figure 1 provides an example of a typical activity and is taken from the

toys theme.

Findings

Pre-intervention language assessment

The pre-intervention scores at school entry in the three schools showed that the

language skills of the children are less well developed than the general population,

with the majority of the children scoring less than a standardized score of 85 (the

lowest score was 64). A score of 85-110 is described in the CELF-Preschool manual

as being 'within the average range'. The range of scores for the two intervention

schools was 64-100 and 64-116. However the scores for the comparison school were

64-73. There was therefore a significant difference between the children's language

functioning in the intervention schools and the comparison school at the beginning of

the year. Only 10 children were admitted to the reception class in September 2002 in

the comparison school and two of these children with considerable language delay

reduced the mean score.

Differences in performance on the six subtests across the whole sample

Receptive language

Linguistic concepts. There was a wide range of scores evident, with a few very low

664 J. Rileyet al.

scores with the mean score of 11.2 (SD 4.4) out of a possiblescore of 20. The

childrenat Vintnersperformedless well than the other two schools, with a mean

score of 7.7 (SD 4.2). The children, whilst some were confused, generally

understoodsimple commandssuch as 'Point to one of the bears' or instructions

with two commands,e.g. 'Point to a dog but not the one who is eating'. The

greatest difficulty was with concepts of 'next to', 'except', 'middle', and 'some',

several children confused 'first'with 'last', and most did not understand 'either/or'.

Basic concepts.Most of the children were more successful on this subtest. The mean

across the sample was 12.4 (SD 4.3) out of a possible score of 18, with the childrenin

the comparison school scoring less well with a mean of 9.4 (SD 5.1). Most children

coped with concepts connected with dimensions of size ('tall' and 'long'), but 'full'

and 'empty' created difficultiesfor some. Lower scoring children did not understand

instructions such as 'Point to the one ... that is empty/who is tall'.

Sentencestructure.Childrenwho scored well on this subtest could use most of the rules

of sentence structure.Those who did poorly found it difficultto respond to sentences

using the interrogative'wh...?' as in 'Where does the boy play cricket?'to which the

child was expected to point to a picture of a cricket pitch. Another difficultywas the

use of complex sentences in which the response depended on understandinga main

clause at the end of the sentence, e.g. 'The man sitting under a tree is wearing a hat'.

The mean score for the whole sample was 13.9 (SD 4.5). The comparisonschool had

a lower score of 10.6, with a wider spread of functioning evident (SD 5.7). The

Vintners children showed a range of 3-18 out of a possible 22 points.

Expressive language

Receptive language is normally in advance of expressive language development and

this appearedto be the case with the majorityof children in the present study.

Recallingsentencesin context.The majorityof childrenfound this subtest very hard. In

Vintners four children were most uncomfortable about expressing themselves aloud

by recalling sentences in context. Children found most difficult those sentences set

within a story which representedtwo ideas, such as 'I am putting tomato sauce and

mustard on my burger'. These they often shortened to 'I am putting some on my

burger!' or even merely '... on my burger'. The mean for the whole group was low,

with the widest range of scores of all the subtests -21.9 (SD 12.3) out of a possible 52

points. The mean for the comparison class was 8.4 (SD 10.8).

Formulating labels. This subtest required the ability to label objects both animate and

inanimate and to know forms and tenses of verbs, e.g. participles. Again, as with the

first test of expressive language, the children in these three schools found this

challenging. They appeared to be unfamiliar with nouns such as 'buttons', 'a band'

(musician type), 'bridge' and verbs such as 'cutting', 'sewing' and 'riding'. The mean

Developing spoken language skills 665

Table la

COPELAND STANDARDIZED SCORES (an intervention school)

Total Language Scores

The table compares standardized scores on first and second tests

First Test

Second Test

Name

(October 2002)

(July 2003)

Cisel

Cheyanne

Annette

Keith

Sina

Renee

Malique

Christopher

Janet

Imam

Shafik

Talek

Nafisa

Amin

Max

Ahlam

Oliver

Mark

Jennifer

Ayca

Tahifa

Abdul

70

96

77

79

73

73

92

73

93

64

64

64

64

77

83

73

92

64

83

64

70

83

84

101

64

84

83

70

100

73

78

99

64

64

64

104

98

77

101

85

102

97

80

83

Mean scoresare 75.9 at pre-testand 84.3 at post-test.

for the sample was 15.3 (SD 8.5), out of a possible 40 points, and for Vintnerswas a

lower mean score 12.7 (SD 4.2), with a much narrower(half) spread of scores.

Wordstructure.This was anotherproblematicsubtest. Many childrenhad trouble with

all aspects of tense and pronouns. Possessive pronouns were a complete mystery.

Children confused 'his' and 'hers' or did not even attempt them. Simple prepositions

such as using 'on' ratherthan 'up' were also confused. The mean was low at 6.9 (SD

4.1) out of a possible 20 points and an even lower mean score at Vintners of 4.4 and

narrow spread of scores (SD 2.8). See Tables la, ib, 2a, 2b, 3a and 3b.

The interventionprogramme

The programmewas planned, discussed and evaluated during the four study days at

the Institute of Education, with the teachersbeing replacedby supply teachersin their

reception classes in orderto provide 'qualitytime' awayfrom the school environment.

666 J. Riley et al.

Table lb

COPEIAND Age equivalents(an interventionschool)

Name

Age equivalentof

Age at second test

total languagescores

Years& Months

Cisel

5.7

Cheyanne

5.6

5.6

Annette

Keith

5.8

5.9

4.1*

4.11

Sina

Renee

Malique

5.9

5.9

5.5

5.3

4.6*

5.2

4.8

Christopher

5.5

4.3*

Janet

Imam

Shafik

5.8

5.5

5.4

5.0

5.2

3.5*

Taiyeb

5.9

3.8*

Nafisa

Amin

Max

5.6

5.5

5.5

3.7*

5.3

5.5

Ahlam

5.5

4.4*

Oliver

Mark

Jennifer

Ayca

Tahifa

Abdul

5.6

5.5

5.6

5.9

5.8

5.6

5.2

4.10

5.7

5.5

4.8

4.7

These study days, supported by the lead author, took the form of seminar-type

activities as the higher education coordinator of the project. The teachers undertook a

course of reading. Careful and thoughtful analysis of the CELF-Preschool assessments informed the teachers about their own pupils and the projects, ideas were

shared and many improvements made to the intervention throughout the year. These

study days proved to be a valuable form of in-service training for the teachers, allowing

time for reflection, sharing and mutual encouragement in order to keep on the agreed

time schedule. The four-day course appeared to have a powerful professional

development element for those involved.

Windsmoor Primary School was quicker to implement the intervention programme. The Fruit project was planned with 12 volunteer-led sessions and ran

through the autumn term 2002 and into the spring term 2003. Copeland used many

of the same materials and their first project with 12 sessions ran in the spring term.

The toy project ran through the rest of the academic year in both schools. Appealing

resources were purchased and made to accompany the themes, including picture

books with supporting materials such as finger puppets to aid the retelling of stories.

The volunteersThe volunteer parents and helpers were vital to the research design.

Both schools had difficulties recruiting the volunteers initially, and inducements

Developing spoken language skills 667

Table 2a

WINDSMOOR STANDARDISED SCORES (an intervention school)

Total Language Scores

The table compares standardised scores on first and second tests

First Test

Second Test

Name

(October 2002)

(July 2003)

Abraham

Moet

Yassin

Aliyah

James

Jagdeep

Mason

Nasmin

Donus

Marta

Kristoff

Shannon

Onemaka

Sujey

Anisa

Jack

Hatice

Shaniqua

Lilian

73

81

91

107

92

64

99

70

82

81

81

108

73

98

64

75

64

82

100

97

103

107

130

101

87

110

70

94

106

101

115

87

121

64

98

64

111

125

Mean scoresat pre-test83.4 and at post-test115.6.

were offered, such as a certificate to be awarded by the Institute of Education at

the end of the year for those who had reliably helped the project. Copeland

struggled most. Windsmoor kept also a register of attendance to encourage

reliability of the seven adults recruited to lead the weekly sessions. Copeland

recruited three people and also used a teaching assistant. Early difficulties included

experimenting with the timing of the training for the sessions and when the

feedback was most effective. The volunteers suffered from lack of confidence

initially but this built up once it became clear that the children would be amenable

and would cooperate fully. The format of the sessions was amended to allow more

activity-based work and a play break for the children halfway through, and then a

recap of what had been done in the first part of the session was built in. This

allowed for recounting/narrativeskills to be used. Furthermore, it provided an

opportunity for a recasting of the happenings in each session in the past tense. The

volunteers became keener, took their sessions conscientiously and appeared to

enjoy the experience.

LessonslearnedThereliability of the volunteers is a key issue. Also, a tension exists

between those parents who would benefit from being involved and those who

668 J. Rileyet al.

Table 2b

WINDSMOORAge Equivalents

Name

Age at second test

Years& Months

Age equivalentof

total languagescores

4.9

5.8

5.9

Abraham

Moet

Yassin

5.5

5.7

5.4

Aliyah

5.5

6.10*

James

5.9

5.11

Jagdeep

5.4

4.2*

Mason

5.5

6.4

Nasmin

Donus

Marta

5.8

5.6

5.5

4.0*

4.11

4.10

Kristoff

5.8

5.4

Shannon

Onemaka

Sujey

Anisa

5.7

5.6

5.0

5.9

6.6

4.3*

6.2*

3.6*

Jack

5.7

5.6

Hatice

Shaniqua

Lilian

5.4

5.7

5.7

3.2*

6.2

7.4*

Table 3a

VINTNERS STANDARDIZEDSCORES (the comparisonschool)

Total LanguageScores

First Test

Name

Second Test

(October2002)

(July2003)

Ezra

Shaikul

Annabel

Darren

Christopher

Henry

Gokhan

Imam

Abdul

Khalik

70

70

64

64

70

73

73

64

64

64

78

64

64

64

70

64

64

64

64

64

Mean scoresat pre-test67.6 and at post-test66.

would lead the sessions effectively. Due to the nature of the catchment area there is

also the issue of parents and their own levels of spoken English and their ability to

be able to offer a good model to the children. The end of project certificate was

seen as recognition and a reward and proved to be a motivator for the volunteers.

Developing spoken language skills 669

Table 3b

VINTNERS AGE EQUIVALENT SCORES (the comparison school)

Name

Age at second test

Age equivalent of

Years & Months

total language scores

Ezra

Shaikul

Ann

Darren

Christopher

Henry

Gokhan

Imam

Abdul

Khalik

5.4

5.7

5.4

5.4

5.7

5.7

5.7

5.4

5.7

5.8

4.4

3.10

3.2

2.7

4.7

4.3

3.5

3.9

3.4

3.7

In June2003, no Vintnerschild was performingat the level of his/her

chronologicalage. All wereat least one year behind.

Training is also vital. Both schools undertook this very seriously. Windsmoor gave

the supporters half an hour (3.00-3.30 pm every Thursday afternoon) before their

own children were collected from school. Copeland trained the volunteers during

assembly immediately before the teaching took place.

Grouping the children was more of an issue at Windsmoor due to the fact that the

intervention took place outside the classroom. Also, the advisability of parents

working with their own children was also a consideration.

It now seems that work should be linked and embedded into the ongoing work of

the class. The fruit theme was very successful. It was multisensory and enabled a

memorablevisit at the beginning of the teaching phase to the local marketto buy fruit.

Language was used for a genuine purpose to ask for a particularpurchase.

The accompanying children's literature has to be carefully chosen. Obviously,

relevant, appropriatefor child retelling, colourful and good quality literarystories are

essential. Story props such as finger puppets are valuable.

The content of the sessions is most effective if linked to the class teaching but

flexible enough if the enrichment sessions fall behind for unavoidable reasons. The

resources, once made, if systematicallylabelled and stored, are useful materialsfor use

across the school to support particularbut often repeated projects and topics. The

quality of these is crucial. See Table 4.

Post-intervention language assessment

The findings of the study are encouraging.All the childrenhad made progressin their

language skills. The greatest gains seen are in expressivelanguage. The largest mean

gains were seen in the Recalling Sentences in Context and Word Structuresubtests.

In the first subtest, the group as a whole made 12 points of progresson the test out of a

possible 52. In Word Structure, Windsmoor gained significantly more than the

670 J. Riley et al.

Table 4. Comparingschools

Increase in or maintenance of scores

Vintners

(N= 10)

Copeland

(N=22)

Windsmoor

(N= 19)

No of children who had increased

or maintained their Receptive Language

standardized scores

No of children who had increased or

maintained their Expressive Language

standardized scores

No of children who had increased or

maintained their Total Language

standardized scores

No of children performing at a level

at or above their chronological age in

both Receptive and Expressive language

5 (50%)

19 (86%)

19 (100%)

8 (80%)

17 (77%)

16 (84%)

1 (10%)

19 (86%)

16 (84%)

0

3 (13.6%)

9 (47%)

comparison school. The two intervention schools gained 13 points compared to the

comparison school, which only moved 8 points. Although only one subtest reached

the level of statistical significance, it would appear that the language enrichment

programmemade a difference to these reception children.

The second largest gain made across the three schools was observed in the

Formulating Labels subtest, with the mean gain being 8 points. Although the

comparison school did not make significantlyless progress, the spread of the scores

are less in both intervention schools where all the children made progress. In other

words the intervention supported all the children to make progress.

Conclusion

Overall, the intervention had a positive effect on the oral language skills of the

reception children;all of them had made progress.However, by the end of the year the

majority of the children were still over a year behind the level of what might be

expected for their chronologicalage. In the comparisonschool all the childrenwere at

least a year behind, with six children 18 months to two yearsbehind. One intervention

school, Copeland, had only 3% of childrenfunctioning at or above the level expected

for their chronologicalage and the other, Windsmoor, had 9% by the end of the year.

These findings indicate the level of need for the intervention in the first place. With

improvements to the materials, further training, and a longer and more intensive

period of intervention there is every reason to expect that this could be further

improved.

The pre-interventiontest scores indicated that the spoken language skills of these

childrenat school entry are depressedin comparisonwith the generalpopulation. The

teachers and the enrichmentprogrammein the interventionschools made a difference

Developingspokenlanguageskills 671

to more of the childrenin their classes than the comparisonschool. However, as a neat

experiment this study was not successful in that the children who received the

enrichmentprogrammedid not make statisticallymore progressthan the comparison

school whose school population was different on several counts.

In the interventionliteraturethe patternand intensity of interventionsis crucial.We

were convinced that with a complex cognitive area of functioning such as spoken

language the children needed a broad, rich and active programme with which they

could engage. This was not narrow skills teaching. Nevertheless, it may be that the

programme was too diffuse and spread out with only one session a week.

Furthermore, it is recognized that the scope of the research is limited because of

the small number of schools involved and the study's overall design. The two

intervention schools were self-selected and the limited funding did not allow for a

matched comparison group to be a possibility. Whilst acknowledging these limitations, the study offers a case study of professional development through action

research and addresses an effort to improve language skills through the use of

volunteers within the school system.

These two teachers wanted to improve their teaching and were motivated to apply

for a BPRS funding and were supportedand encouragedby the local higher education

institution. They put in a great deal of extra effort to make this happen at all. The

comparison school was the closest neighbourhood school. The greatest value of the

year was the benefit that the teachers gained from the project. This provided

opportunity for learning about the acquisition of spoken language, its various facets

and complexity through self-study and discussion. The teachers became more aware

about what appears to support development of spoken language in a classroom

situation. The childrenbenefited from languageenrichmentand greateradult support

for their learning than previously.

References

Basic Skills Agency (2003) Youngchildren'sskills on entryto education(London, Basic Skills

Agency).

Catts, H. W. & Kamhi,A. G. (Eds) (1999) Languageand readingdisabilities

(Boston,MA, Allyn&

Bacon).

Chaney, C. (1994) Languagedevelopment,metalinguisticskills and emergentliteracyskills of

three-year-oldchildrenin relationto social class,AppliedPsycholinguistics,

15, 371-394.

Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) (1998) The National LiteracyStrategy:

frameworkfor teaching (London, DfEE).

and CurriculumAuthority(DfEE/

Department for Education and Employment/Qualifications

QCA) (1999) The National Curriculum:handbookfor primary teachersin England (London,

DfEE/QCA).

Department of Education and Science (1990) English in the National Curriculum(London, Her

Majesty'sStationeryOffice).

Dockrell, J. E. & Lindsey, G. (2001) Children with specific speech and language difficulties-the

teachers' perspectives, OxfordReview of Education, 27, 369-394.

Dockrell,J. E., Stuart,M. & King, D. (2003) Supportingearlyoral languageskills:rationaleand

evidence (in press).

672 J. Riley et al.

Geva, E. (1997) Issues in the development of second language reading: implications for instruction

and assessment, paper presented at the International Workshopon Integrating Literacy,

Researchand Practice, 13-14 March, London.

Goodman, K. & Goodman, Y. M. (1979) Learning to read is natural, in: L. Resnick & P. Weaver

(Eds) Theoryand practice in early reading (vol. 1) (Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum).

Halpern, D. F. (1992) Sex differencesin cognitiveabilities (Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum).

Hart, B. & Risley, R. R. (1995) Meaningful differencesin the everyday experienceof young American

children(Baltimore, MD, Paul Brookes).

Kotler, A., Wegerif, R. & LeVoi, M. (2001) Oracy and the educational achievement of pupils with

English as an Additional Language: the impact of bringing 'talking partners' into Bradford

schools, InternationalJournal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 4, 403-419.

Leonard, L. B. (1997) Children with specific language impairment (Cambridge, MA, The MIT

Press).

Lindsay, G. & Dockrell, J. (2002). Meeting the needs of children with speech and communication

needs: a critical perspective on inclusion and collaboration, Child Language Teaching and

Therapy, 18(2), 91-101.

Locke, A. & Peers, I. (2000) Development and disadvantage: implications for the early years and

beyond, paper presented to the International Special Education Congress, University of

Manchester, July.

Locke, A., Ginsberg, J. & Peers, I. (2002) Development and disadvantage: implications for the

early years and beyond, InternationalJournal of Language and CommunicationDisorders,37, 315.

National Literacy Trust (2001) Early years language survey (London, National Literacy Trust).

Pearson, B. Z., Fernandez, S. C., Lewedeg, V. & Oller, D. K. (1997) The relation of input factors

to lexical learning by bilingual infants, Applied Psycholinguistics,18, 41-58.

Peers, I. S., Lloyd, P. & Foster, C. (1999) British standardisation of the CELF. The Psychological

Corporation's speech and language assessment.

Peers, I. & Locke, A. (1999) Teaching spoken language in the early years. Poster presentation to

the ThirdInternationalSymposium:Speechand LanguageImpairments-From Theoryto Practice,

University of York, 21-25 March.

Resnick, J. S. & Goldfield, B. A. (1992) Rapid change in lexical development in comprehension

and production, DevelopmentalPsychology,28, 406-413.

School Curriculum and Assessment Authority (SCAA) (1997) Use of language: a commonapproach

(London, SCAA).

Semel, E. M., Wiig, E. & Secord, W. (1987) Clinical evaluation of languagefundamentals-revised

(San Antonio, TX, Psychological Corporation).

Sticht, T. G. & James, J. H. (1984) Listening and reading, in: P. D. Pearson (Ed.) The handbookof

readingresearch(New York, Longman).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986) Thoughtand language (3rd edn) (Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press).

Wells, G. (1987) The meaningmakers:childrenlearninglanguageand usinglanguageto learn (London,

Hodder & Stoughton).

Whitehurst, G. J. (1997) Language processes in context: language learning in children reared in

poverty, in: L. B. Anderson & M. A. Romski (Eds) Communicationand language acquisition:

disordersfrom atypical development(Baltimore, MD, Paul Brookes).