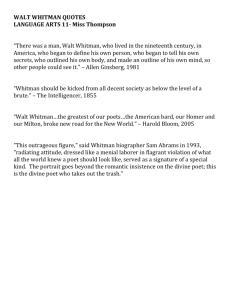

UNRAVELING WALT WHITMAN George Constantine Cristo

advertisement