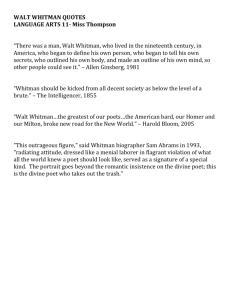

Whitman, Transcendentalism and the American Dream

advertisement