The Rules of Offer and Acceptance

advertisement

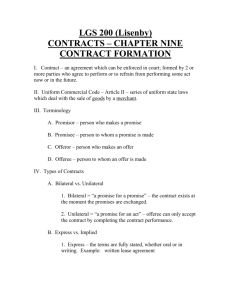

Lec Notes Wk 6.doc SCHOOL OF BUSINESS INTRODUCTION TO COMMERCIAL LAW BSQA 510 LECTURE NOTES: WEEK 6 TOPIC 3: THE LAW OF CONTRACT The Rules of Offer and Acceptance A. Offer To find out whether there has been offer and acceptance we look to see: If one party has expressed a willingness to be legally bound on definite terms. This will be Law the Offer. - An The party is the Offeror; and i Has the other party expressed a willingness to be bound on the same terms. This will be the Acceptance. This party is known as the Offeree. There is no statute law on offer and acceptance. It is all based on case law. The case law is not so much concerned with the inner mental processes of the parties. It deals more with outward, or external, signs which clearly indicate the existence of an agreement. WHAT IS AN OFFER? i. Definition An offer is some action signifying that a person is willing to enter into a contractual relationship if their proposal is accepted. It should be noted that an offer can be merely verbal (i.e. spoken words), or it can be in writing, or it can be implied by conduct. Offers can be made to individuals, or to a specific group of people, and in exceptional cases to the whole world. The leading case on what an offer is, is the Carlill case. We have already seen that the court rejected, in those circumstances, the defendant's claim that there was no intention to enter into legal relations. The defendant then claimed that the promise was not binding because the promise was not an offer to a specific person, or to a group of persons. The defendant said it was an offer made to all the world, i.e. not to anybody in particular. On this basis the promise was not binding. The court rejected this argument. The judges said the offer was not just to nobody but to anybody who performed the conditions. It was an offer to become liable to anyone who performed the conditions. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 1 ii. Invitations to treat Offers however must be distinguished from invitations to treat, i.e. an invitation to bargain. An invitation to treat is not an offer. There are a number of different types of these "invitations to treat". ■ A Response to a Request for Information Sometimes you may make a request for information in relation to some potential transaction. Any response to a request for information is never an offer, it is only an invitation to treat (Harvey v Facey [1893] AC 552). In Harvey the facts were that in the course of negotiations for the sale of a property (known as Bumper Hall Pen) Harvey telegraphed Facey. The words of the telegraph read: "Will you sell us Bumper Hall Pen? Telegraph us your lowest cash price...". Facey replied by telegraph with the words: "Lowest price for Bumper Hall Pen £900". Harvey then telegraphed back: "We agree to buy Bumper Hall Pen for the sum of nine hundred pounds being asked by you". The question for the court was whether Facey's reply of "Lowest price for Bumper Hall Pen £900" constituted an offer which became a contract on receipt of Harvey's acceptance, or whether it merely supplied information to Harvey, i.e. so that it contained no implied promise to sell the property for £900. The court decided that there was no implied promise and that only if Facey had accepted the offer in Harvey's second telegram would there have been a contract. ■ Statements of Intention Another type of invitation to treat is a statement of intention. These occur when a person announces their intention to buy, sell or deal with some property. Such a statement is not an offer (Harris v Nickerson [1873] LR 8 QB 286). ■ Shop Displays Generally, shop displays are also classified as invitations to treat. Shop displays cover actions designed to entice offers from others. Those 'others' being the customers. Price lists, catalogues, advertisements and signs are also usually classified in the same way. The leading case on the matter is Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britian v Boots Cash Chemists Ltd [1953] 1 All ER 482 . iii. Communication of the Offer All the terms of the contract must be communicated to the offeree. Terms that are not made known are not part of the offer and will not be part of a binding contract. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 2 iv. Termination of an Offer When does an offer end? In this regard an offer may end because of an acceptance, a rejection, a lapse, or a revocation of the offer. ■ Acceptance When an offer is accepted, it comes to an end. In its place you have an agreement. ■ Rejection Rejection occurs when the offeree (by words or conduct) refuses the offer. Therefore, when an offer is refused the offer comes to an end and cannot be accepted later on. ■ Lapse The passing of time may also cause an offer to lapse (e.g. “Offer open until 5 November 2008”). In Ramsgate Victoria Hotel v Montifiore [1866] LR1 Ex 109 the defendant had offered to subscribe for shares in the plaintiff company. Nearly six months elapsed between the date of applying for the shares and notification that shares had been allotted to the defendant. The defendant refused to accept the shares once allotted. The court held that the period, the defendant had been made to wait, was unreasonable. Therefore his offer had lapsed and there was no contract. ■ Revocation An offer can also be terminated by revocation. This occurs when the offeror withdraws the offer they have made. An offer can normally be revoked at any time prior to its acceptance. This is so even if the offer was originally stated to remain open for a fixed period. But note that this may be misleading or deceptive conduct under the Fair Trading Act 1986 (Week 11 topic). In Routledge v Grant [1828] 4 Bing 653 the defendant made an offer to buy the plaintiff's house. The plaintiff was given six weeks to accept. The defendant withdrew his offer within that six week period and the court held that he was fully entitled to do so. However, if there is a separate contract stating that the offer will stay open for a certain period, will there be no right to revoke. This amounts to an option contract. The option to accept remains open during the relevant period (cannot be revoked). A revocation must be communicated to the offeree. In Stevenson v McLean [1880] 5 QBD 346 Stevenson and McLean were negotiating over the sale of iron. The defendant McLean offered to sell a certain amount of iron at a certain price to Stevenson. The offer was to remain open until Monday. The defendant (McLean) later sold the iron to a third party and sent a telegram informing the plaintiff (Stevenson) of the sale and so revoking his offer. But before Stevenson had actually received this telegram he sent his own telegram to McLean accepting the offer. The two telegrams crossed. The court held that McLean did have the right to revoke his offer at any time before acceptance by Stevenson, but also that Stevenson had actually accepted the offer (by his telegram) before receiving notice of the revocation. The result was that there was a binding contract. Therefore an offer can be revoked at any time but it must be revoked before acceptance. In this case acceptance occurred when Stevenson sent his telegram of acceptance not when BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 3 his telegram of acceptance arrived at McLean's office (this is known as the Postal Rule, discussed later). For revocation to be effective it must actually reach the offeree and so the time when it is sent is not relevant. Usually the revocation is communicated by the offeror, but it can be communicated by others. (Dickinson v Dodds [1876] 2 Ch D 463, where revocation of Dodds‟ offer to Dickinson was communicated by a mutual friend.) B. Acceptance i. Definition An acceptance is any act which shows an intention to be legally bound by the terms of an offer. This means that the acceptance of the terms of the offer must be without qualification (no strings attached). We already know that an offer can be made to an individual, or to a class of person, or indeed to the whole world at large (refer to the Carlill case). Where an offer is made to a specific individual only that person can accept it. If the offer is made to a group of persons then anyone in that class or group can accept it. But if a person is not included in that group they cannot validly accept the offer. ii. Acceptance must be communicated to the offeror It is not enough that the offeree merely decides to accept the offer. There must also be some positive act which constitutes acceptance. So generally: a) Acceptance must be by an overt, e.g. written words, spoken words, or some course of conduct; and b) Must be sufficiently communicated to the offeror. The law of contract will not allow acceptance by default. For example, silence on the part of the offeree cannot be deemed to be an acceptance. In Felthouse v Bindley [1863] 142 ER 1037 the plaintiff (an uncle of the defendant) wrote to his nephew offering to buy one of his horses for a certain sum. The plantiff‟s letter included words to the effect that if he heard nothing more from his nephew he would consider the horse to be his. The nephew made no reply. The horse was later sold by mistake to a third party. The court held that there was no binding contract between the uncle and the nephew. An offeror cannot impose contractual liability upon an offeree merely by proclaiming that silence shall amount to acceptance. So the rule is that there must be an act of acceptance and this act must be communicated to the offeror, but communication is sufficient by some course of conduct taking place that fits within the terms of the offer. Where the offer indicates a particular method of acceptance, then it can be carried out that way or by using a quicker method (Manchester Diocesan Council for Education v Commercial and General Investments Ltd [1970] 1 WLR 241). However, if the offer states that an acceptance can be made only by one method, then acceptance must occur that way. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 4 However there are some distinct qualifications to the rule that acceptance must be sufficiently communicated to the offeror. a) Bilateral vs Unilateral contracts Most contracts are bilateral, i.e. the agreement is based on an exchange of promises. However in a unilateral contract only one side makes a promise, and in exchange for their promise they receive, not another promise but, an act. The most common form of unilateral contract is an advertisement for a reward. Here Party A offers (i.e. promises) a reward to anyone returning a lost item. Party B will make the contract by performing the act specified in Party A's offer, i.e. finding the item and returning it. Party B cannot really promise to find the article. Therefore, at no time does Party B make any promise to Party A. So unilateral contracts consist of offers where it is not practical to communicate any acceptance by promise. Instead the acceptance will consist of the doing of an act. Another example of a unilateral contract is found in the case of Carlill. There, of course, the defendant made an offer to the whole world by their words in a newspaper advertisement. The court held that acceptance occurred when the product (i.e. the carbolic smoke ball) was bought and used as directed. b) The Postal Rule These rules provide that where a letter is used as the method of communicating the acceptance, then acceptance is complete on the posting of the letter. Note, however, that the postal rule only applies where acceptance must be, or can be, by post. This should also apply to couriers, although there does not seem to be any decided case exactly on this point - but by analogy the situation is similar. Where acceptance must be or can be by post, the posting of the acceptance can be expressly required or implicitly allowed. For example, the offer may state something like "Reply by post". The offer expressly states that the posting method must be used. Also, posting may be implicitly allowed, e.g. during negotiations the offer may have been posted. Hence it is implied that the acceptance can also be posted back by the offeree. The leading case is Adams v Lindsell [1818] 106 ER 250. In the case Lindsell wrote and offered to sell wool to Adams. An answer was required by post. However because the offer was incorrectly addressed Lindsell's letter arrived late. Nevertheless an acceptance was immediately posted back by Adams. Lindsell had not yet received the acceptance and thought that he was not going to receive a reply to his offer. Not having received an early reply from Adams, Lindsell sold the wool to a third party. But Adams had already posted his letter of acceptance. The next day Lindsell actually received Adams' letter of acceptance. The court held that the contract was complete when the acceptance was posted. Avoiding the Postal Rules The postal rule can be avoided by specifying in the offer that another means of acceptance has to be used or that acceptance must reach the offeror before a binding contract will exist. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 5 It should be noted that the postal rules apply to telegrams as well as letters, but it has been established in Entores Ltd v Miles Far East Corp [1955] 2 All ER 493 that telexes and telephone messages do not come within the posting rules. Therefore neither does a fax. The grounds for distinguishing telexes, telephone messages, faxes, and emails, etc., from letters and telegrams, is that these are instantaneous means of communication. But with letters there is always a period of time between when they are sent and actually received. The general understanding has been that for instantaneous communications the acceptance is at the time the message is received. c) Emails For electronic communications, the position has now been clarified by the Electronic Transactions Act 2002, contains default rules (i.e. they can be varied by the parties) relevant to contract formation. Electronic communications, such as emails, are deemed to be sent when they enter an information system outside the sender‟s control (s.10), and to have been received when they enter an information system designated by the recipient for the purpose of receiving electronic communications (when there has been no such designation, then receipt is when the electronic communication comes to the attention of the recipient) (s.11). The place of dispatch and receipt is the sender‟s and recipient‟s place of business respectively, unless there is no place, or there are multiple places (ss.12, 13). Therefore, it is possible for an „email‟ to be „received‟, yet not have been read by the offeror. iii. Responses which are not acceptances There are types of responses that are not acceptances. These are: ■ Inquiry as to Change of Terms A query about changes in the offer does not amount to a rejection of the offer. The offer can still be accepted later. ■ Counter-offer A counter-offer has two distinct parts: A rejection of an offer; and The provision of a replacement offer. The original offer is ended by the rejection. If the replacement offer is accepted then a contract is made. A case example of a rejection and then a counter-offer, is Hyde v Wrench [1840] 49 ER 132. Wrench offered to sell a property to Hyde for £1000. Hyde counter-offered £950. Wrench refused this offer. Next Hyde wrote to Wrench offering to pay £1000. Hyde claimed that a contract existed. The court held that there was no contract. The counter-offer of £950 amounted to a rejection of the original offer of £1000. iv. Consensus ad idem At the end of the offer and acceptance process the parties should have reached consensus ad idem. This means that a meeting of minds has occurred. This rule requires a complete agreement. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 6 The leading case is May & Butcher Ltd v The King [1934] 2 KB 17 where the plaintiff agreed to buy surplus tents from the government at "a price to be agreed from time to time". In fact, disagreements about the price occurred from time to time. The court held that there was no contract because the parties had failed to agree to an essential term, i.e. the price. In other words, there was not a complete agreement. In Bouma v Bust (1998) 6 NZBLC 102, 456, it was held that if lay parties conduct negotiations and record what they believe is the outcome, this may be a sufficient meeting of minds to create a contract even though strict identification of offer and acceptance is not possible. The Court of Appeal decided that Courts should take a practical approach to the circumstances of the case. Consideration A. Definition What is consideration? It is "the price of the promise". Consideration is the value or benefit given by one party in return for the promise made, or act done, by the other party. Law - An Most contracts are bargains, and consideration is an essential part of the bargain. Usually i a promise is not binding if it is given for nothing. The promise will only be legally binding if the other party has supplied something in return (and what is supplied in return can be another promise or an act). That which is supplied in return is called the consideration for the promise, e.g. one ice-cream in return for $1.00. All contracts must be supported by consideration. But this is subject to one exception and that is contracts made in the form of a deed. B. Contracts by Deed The important thing about a deed is that it does not need to have consideration. Deeds are enforceable simply because of their formal structure. In day to day business, contracts are not normally made by deed. Important contracts can however be made by deed (e.g. a Deed of Lease or a Deed of Trust). If a contract is not made by deed then it is called a SIMPLE CONTRACT. C. Executory versus Executed Consideration There are two categories of consideration. These are EXECUTED (something is actually done) and EXECUTORY (a promise to do something). To support a simple contract consideration may be either executory or executed. Consideration is called “executory” when the promise of one party is made in return for a counter-promise from the other party, e.g. an agreement for sale of goods on credit for future delivery so that one party promises to deliver the goods and the other party agrees to pay at some future due date. In this case when the agreement is made nothing has been done to fulfil the mutual promises and so the actual transaction remains in the future but the contract is still binding. I.e., no money needs to change hands for a contract to be binding. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 7 Consideration is „executed‟ when the promise of one party is made in return for the performance of an act, e.g. the offer of a reward. If I advertise a reward for the return of my lost watch, then the return of the watch is at once the acceptance of the offer and the required consideration for the promise. It doesn‟t matter whether consideration is an act or a promise. Both executory and executed consideration can support a contract. D. Adequacy and Sufficiency of Consideration “Consideration must be sufficient but it need not be adequate”. To be sufficient in the legal sense, consideration must be: real; and valuable. "Real" means any thing or any service or any forbearance and "Valuable" means only that it has to have some value, however slight. Consideration need not be adequate. This means that it need not be a fair exchange, or a bargain for equal value. This is because the courts believe individuals should have freedom to contract and the relative values in the exchange is up to the parties to decide. An illustration of this principle is found in Thomas v Thomas [1842] 2 QB 85. Here the husband, shortly before his death, expressed the wish that his wife should have the use of his house during her lifetime (after the husband died). For this purpose the executor of the husband‟s will agreed to allow the widow to use the house for a rent of only £1 per annum. Later the executor changed his mind and refused to allow the widow the use of the house. The widow took the matter to Court. The executor claimed that there was no consideration and therefore no contract. The court held that the sum of £1 was sufficient consideration although it was far less than the actual benefit that the widow received. Note however that Parliamentary legislation may require the courts to look at the adequacy of consideration in specific cases, e.g. under section 5 of the Minors Contracts Act 1969. However some types of apparently valuable consideration are also insufficient (i.e. cannot be used as consideration). In this regard we look at two situations. These are: i) Existing contractual duties "Existing contractual duties" cover the situation where a person has already entered into a contract. The performance of that contract, or an obligation under it, cannot be consideration to support another contract. This was made clear in the case of Stilk v Myrick [1809] 2 Camp 317. In this case several crew members of a ship deserted the ship before its return to England. The captain promised extra wages to the remaining crew if they worked the ship short-handed. On arrival in England the owner of the ship refused to pay the extra wages. The question was whether there was consideration for the captain's promise. The court held, "no". The crew had only performed what they were bound to do under their contract, i.e. sail the ship home to England. But if a person goes beyond their existing obligations this may provide fresh or separate consideration for a new promise. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 8 ii) Public duties "Public duties" cover the situation where a person is already under a duty to perform a public service or duty. Again the performance of that service or duty cannot be consideration to support another contract. The case of Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan County Council [1925] AC 270 is a good case demonstrating both this point and the point that if a person goes beyond the public service or duty then this may constitute separate consideration for an additional contract. In the Glasbrook Bros case the defendants were coal mine owners. During a miners' strike, and picket, the defendants requested a resident police garrison to protect the mine. The police considered this unnecessary but agreed to provide the garrison only on the condition that the mine owners paid for the extra service. After the strike ended the mine owners refused to pay for the extra service as they considered it within the ordinary duties of the police force to provide such protection. The question that arose was, was there consideration for the payment promised? The court held that the police decision, to initially refuse the protection requested, was a reasonable one. By providing the garrison the police had done more than their public duty and so were entitled to be paid. E. Past Consideration Past consideration is not sufficient to support a contract. The rule is that “past consideration is no consideration”. For example, Party A has done an act and Party B later promises to pay for that act. There is no contract. Party A has not given any (present or future) consideration for Party B's promise. The case of Re McArdle [1951] 1 ALL ER 905 demonstrates the point. Here the deceased left a life interest in his house to his wife. A life interest is the right to occupy or derive the rent from the house. Upon the wife's death the arrangement was that the children were to inherit the property. Now during the wife's lifetime one of her sons and his own wife lived with her in the house. The daughter-in-law carried out improvements to the house thereby enhancing its value. The children later signed a document stating that they would pay the daughter-in-law £488. However the children later refused to pay. The daughter-in-law sued. Was there a contract on which to base her claim? The court held, "no". The improvements were carried out before the document was signed so there was past consideration. An exception arises when it is proved that services were provided at the request of the promisor (i.e. the person making the promise to pay). This will be sufficient consideration to support a later promise to pay (even though no mention of payment was made at the time). A case that demonstrates this is that of Lampleigh v Brathwait [1615] Hob 105 80 ER 225. In this case, Brathwait had been sentenced to death for murder. Brathwait requested Lampleigh to travel to London to obtain a royal pardon for him. Lampleigh was successful in obtaining the pardon. Therefore Brathwait promised to pay him £100 for his services. However Brathwait later refused to pay, claiming that there was no consideration for the promise. The court held that there was a contract with consideration from both parties at the outset and only the amount of payment had not been agreed. It was implied that Lampleigh would be paid for the requested service. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 9 F. Consideration must be legal An illegal consideration cannot support a valid contract. Obviously a promise to perform a criminal act is illegal consideration. However some acts that are not obviously criminal may also amount to illegal consideration. G. Part payment of a debt is insufficient consideration The general rule at common law is that a promise by a creditor to accept less than the total amount of the debt from the debtor is not binding. Such a promise is not binding because it is not supported by consideration or fresh consideration on the debtor's side. This rule was laid down in Foakes v Beer in 1884. In the case of Foakes v Beer [1884] 9 App Cas 605 , Dr Foakes owed a debt of £2,090 to Mrs Beer. Mrs Beer agreed with Dr Foakes that he could pay the debt by a deposit of £500 and pay the rest in monthly instalments. On this basis Mrs Beer agreed that she would not take further action against Dr Foakes if he would pay in this manner. Dr Foakes did pay in full and Mrs Beer then claimed a further £360 to which she was entitled to as interest for late payment of the debt.The question was: had the debt been discharged by the payments made under the agreement, so that Mrs Beer could not claim the interest? The court held, "no". Dr Foakes had not provided any consideration to Mrs Beer for her agreement not to take further action. However there are three exceptions to the rule that part payment of a debt is insufficient consideration for a promise to discharge the whole debt. These are: 1. Under section 92 of the Judicature Act 1908 it is possible for the creditor or his/her agents to make a written acknowledgment of receipt of part of the debt in satisfaction for the whole debt. This will discharge the whole debt; 2. Where a third party voluntarily makes part payment to a creditor on the condition that the debtor is released from the rest of the debt and the creditor agrees to this condition. This happened in the case of Hirachand Punumchand v Temple [1911] 2 KB 330. The defendant owed a large debt to a money lender. Being unable to pay, the defendant asked his father for help. The defendant's father offered the money lender a sum smaller than the debt owed in full settlement of the debt. The plaintiff (i.e. money lender) accepted the money from the defendant's father and then sued the defendant for the remainder. Did the acceptance of the smaller sum discharge the debt? The court decided, "yes it was". It said that it would be unfair to the third party (i.e. the defendant's father in this case) to allow the creditor to sue the debtor for the remainder of the debt. When the creditor accepted money from the third party the debt was entirely discharged. This means that there is an equitable exception to the rule in the case of third parties paying on behalf of others in these type of cases. 3. The payment of a lesser sum by the debtor plus the giving of some extra benefit for settlement of the whole sum can be sufficient consideration if accepted by the creditor. As long as the something extra is sufficient, i.e. real and valuable (e.g. paying before the due date). Note that the giving of a cheque for a lesser sum instead of cash does not amount to consideration. This argument was tested by a defendant in the case of D & C Builders v Rees [1965] 3 ALL ER 837 and was rejected by the court. BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 10 Space for Your Own Notes!! BSQA 510 Introduction to Commercial Law 11