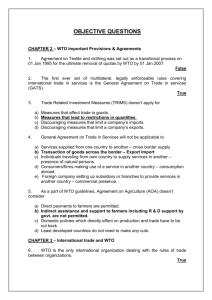

Indonesia: Strategy for Manufacturing Competitiveness Vol. II. Main

advertisement