The Economic Contribution of Indonesia's Forest

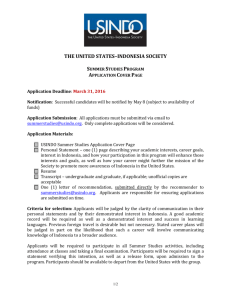

advertisement