killing the death penalty

advertisement

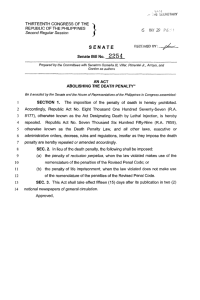

During an unprecedented flurry of closely watched executions and celebritydriven protest this winter at San Quentin, emboldened activists predicted that California could soon abolish the death penalty. Reporting from inside the media circus, About a thousand protesters rally outside San Quentin a month before Stanley “Tookie” Williams’s execution. Many came to hear rapper Snoop Dogg speak. JAIMAL YOGIS KILLING THE DEATH PENALTY P H OTO G RAP H BY G E O R G E N YB E R G ; O P P O S ITE PAG E BY JAI MAL YO G I S discovers that their prophecy isn’t as far-fetched as it sounds. A few days after Allen’s execution, I drove up to Sacramento to meet Donald Heller. He sat casually behind a huge desk, his numerous diplomas and awards mounted proudly behind him. The first thing I realized was that this guy is not a flip-flopper. A longtime Republican, Heller still thinks that sex offenders should be put away for life and that recent criticism of prosecutors is largely unjustified. He concedes that the conservative movement has passed him by, going so far to the right that he sometimes feels like a lefty. But everything from his red striped shirt to the watercolor painting of an aircraft carrier mounted on his office wall screamed Republican and happy to remain so. What Heller is, he said, is able to admit when he’s wrong. “The death penalty is something that a civilized society should not take part in,” Heller told me. “It should be abolished.” Heller began to oppose the death penalty a few years after becoming a private defense lawyer in 1977. It became clear to him that everyone had a story and that many cases would always be ambiguous. Further research taught him that the death penalty he created discriminates against the poor and people of color, costs the state too much money, and doesn’t even act as a deterrent to homicides. He stayed mostly silent about his switch until the execution of Tommy Thompson in 1998. “I don’t think Californians appreciate how wrong that execution was,” he said. Thompson was executed at San Quentin for the rape and murder of Ginger Fleischli. But the evidence for rape—which made the case eligible for death—was shaky at best. Jailhouse snitches clearly lied in their testimony against Thompson, and the coroner’s report suggested Fleischli may not have been raped at all. Though he had nothing to do with the case, it still haunts Heller. A realist, Heller knows he might not see the abolition of the death penalty in his lifetime. Still, if people learned the facts, if they realized that life without parole is a real alternative to state executions, he thinks the majority would oppose the penalty. “The people voted 133 PHOTOGRAPH BY JEFFREY BRAVERMAN Former prosecutor Donald Heller, in his private law office in Sacramento, says his Republican friends used to tease him for opposing the death penalty law that he wrote. “They don’t anymore,” he says. “I take it too seriously now.” At right, Snoop Dogg waits outside San Quentin for his turn to speak at a November Save Tookie rally. This his very busy winter, as San Quentin prepared to execute three men in three months, anti–death penalty activists noticed they had a strange ally. He wasn’t a celebrity protesting alongside Snoop Dogg before the infamous execution of Stanley “Tookie” Williams, nor a candle-carrying activist at the subsequent midnight killing of Clarence Ray Allen. He wasn’t a Catholic priest moved to preach against capital punishment by the church’s suddenly strong stand against it, nor a member of the new state-appointed commission investigating California’s capital system. No, Donald Heller, a man nicknamed “Mad Dog” for his hard-nosed ways as a prosecutor, has his own claim to fame, one in which socalled abolitionists were taking special comfort. In 1977, shortly after a stint as an assistant U.S. attorney, Heller wrote the Briggs Initiative, the proposition that brought the death penalty back to California in a big way. The night the 76-year-old Allen was executed, Natasha Minsker, the ACLU’s San Francisco–based anti–death penalty advocate, told me about Heller. We were outside San Quentin, Minsker bundled in a fauxsheepskin coat and a fleece cap, and we could see our breath in the cold air. Few of the people protesting could believe the state was about to execute a disabled senior who was legally blind. Even the former warden of San Quentin, who supports the death penalty, asked the governor to spare Allen as “an act of decency”—and this from a man who ruled over a prison at times criticized for inhumane conditions. The turnout for Allen’s execution was fairly small compared to that for Williams’s, and I later asked Minsker if she thought California would just go numb to increasing executions. “I don’t think so,” she said. “Just look at the demographics of California. The increasing number of Catholics, the young population. It’s easy to get distracted by these executions, but the death penalty’s days are definitely numbered.” Then she mentioned Heller, citing his recent work on the political campaign to put a moratorium on California executions. “You know the death penalty’s losing speed when the guy who wrote the law opposes it,” Minsker said. MARCH 2006 SAN FRANCISCO JAI MAL YO G I S T SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 134 It was a crisis Bay Area abolitionists must have known they needed: a controversial execution case that would rally the media and get the public involved. For them, the “Save Tookie” campaign fell like manna from heaven. It filled the airwaves from Thanksgiving to Christmas, supplying celebrities, fund-raising opportunities, and reams of news stories. On the night of Williams’s death, candle-holding activists packed the San Quentin waterfront like a sea of Christmas lights. They surrounded hordes of TV news teams, the anchors waiting in heavy makeup. For every activist, there seemed to be at least two cameras. As the executioner fumbled to find the “kill” vein in Williams’s muscular arm, I stood next to three Catholic schoolgirls who had come from the East Bay with their art teacher to pray and protest. They looked so sincere with their candles, I couldn’t help snapping a few photos. But within minutes, a swarm of news photographers saw what they were missing and descended like vultures. “Make them stop,” one of the girls pleaded as the photographers stumbled over each other for tomorrow’s front-page shot. The crowd was more diverse than ever, making the event resemble a somber Burning Man party that got crashed by the Walnut Creek PTA. One man was parading around with a huge papier-mâché Gandhi on wheels, and a group of elderly Catholic women was singing hymns. While Angela Davis gave a speech about injustice, a born-again Christian told me how abortion and the death penalty were really the same issue. And while Jesse Jackson preached redemption, some conspiracy theorist explained to me how Bush planned 9/11 and that CBS and the CIA were happily working together again. The scale of protest and media presence was unprecedented at the prison, but with the coverage in the months leading up to the execution, it was no surprise. The San Francisco Chronicle called for clemency, and newspapers around the world were awash in sympathetic coverage. Beyond the usual chorus of pro and “Make them stop,” one of the girls pleaded as the photographers stumbled over each other for tomorrow’s front-page shot. At recent anti–death penalty rallies, believers of many faiths showed up to protest state killing. Stefanie Faucher and Lance Lindsey (left) run Death Penalty Focus from a three-room office in the Flood Building. Jesse Jackson, Danny Glover, Mike Farrell, and other high-profile figures sit on the organization’s boards. P H OTO G RAP H BY J E F F R E Y B RAV E R M AN ; O P P O S ITE PAG E BY JAI MAL YO G I S It may seem far-fetched to think that California might abolish the death penalty. The state has a well-earned reputation for hard-line anticrime measures like the three-strikes law. It’s still considered political suicide for a candidate for higher office to oppose capital punishment. But during these last few executions, many abolitionists were saying that a tipping point is near. More politicians are openly opposing the death penalty and considering legislation requiring a moratorium on executions while the capital system is investigated. Religious institutions, including the Catholic Church, are also taking a stronger stand. Lance Lindsey, executive director of California’s largest abolition organization, Death Penalty Focus, believes capital punishment may not have 10 years left in this state. Minsker agrees. Franklin Zimring, a law professor at UC Berkeley who has studied death penalty trends for 40 years, says, “Death penalty abolition is absolutely inevitable. The question is when, and what institutions will be involved.” For three months, I attended just about every protest and stole time from the politicians, activists, scholars, church workers, and legal experts who were caught up in the moment. Could Lindsey, Minsker, and Zimring possibly be right? Yes, the signs of potential abolition have long been there in San Francisco, where the majority of residents are plain sick of executions in their backyard. Our own district attorney, Kamala Harris, in her inaugural address, vowed to never seek the death penalty. A poll showed 70 percent of the city supported her when she chose not to seek death even for cop killer David Hill. Many, if not most, of the elected officials, wealthy do-gooders, and human rights organizations who oppose capital punishment in California are here. Noe Valley has been dubbed “Death Valley” due to the number of defense lawyers there who have worked to stop or delay executions. What surprised me was that public opinion in the rest of the state has been steadily catching up. Twenty years ago, before the words DNA testing and wrongful conviction and exoneration meant much to the public, 83 percent of Californians supported the death penalty. But a poll in 2004 found support down to 68 percent. When you ask a nuanced question, the public’s wavering becomes clear. Another poll revealed that when given the choice between sentencing someone to life imprisonment and to death, 53 percent of Californians would choose life without parole. And in one 2000 poll, 73 percent supported a moratorium on capital punishment until a study of its fairness could be completed. Nearly 650 prisoners wait on California’s death row, more than in any other state. And although, as of press time for this piece, we had executed only 13 since the death penalty’s return, experts say we may see multiple executions per year from now on, a process activists are calling “Texafication.” (Texas has executed 357 since 1982.) Zimring believes that as executions increase in frequency, public support will keep falling. “One of the things that Williams became is a catalyst,” Zimring says. “All of a sudden, California has three executions in three months. Now three executions is a terrible yawn in Texas or Oklahoma or Virginia. But in California, it’s a terrible crisis.” G UTTE R C R E D I T H E R E the death penalty law in,” he said. “They’re the only ones who can vote it out.” In the midst of the media circus, I turned to Professor Zimring for perspective. His desk on the third floor of Boalt Hall held an impending avalanche of charts and statistics. The eloquent, mustached man with an odd fetish for elephant sculptures recently published a dense book called The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment, which he references like the Bible. Zimring explained that abolition will happen in California 137 PHOTOGRAPH BY JEFFREY BRAVERMAN San Francisco attorney Jon Streeter was appointed by the state senate to make sure California doesn’t kill an innocent person. Though he supports the death penalty narrowly, he says the state is dangerously close to that nightmare. At right, the ACLU’s Natasha Minsker and former M.A.S.H. star Mike Farrell are two of California’s most powerful abolitionists. abolitionist brunch in Sausalito, emceed by former M.A.S.H. star Mike Farrell. From a living room overlooking Richardson Bay, Farrell recalled his 40 years on the abolition campaign, while philanthropists and defense lawyers nibbled on quiche and drank orange juice. “There are three reasons politicians support the death penalty,” said Farrell. “Politics, politics, politics.” As he spoke, CNN and Fox News kept his cell phone ringing. Farrell is now the president of the board of the San Francisco–based Death Penalty Focus, and he is a major reason other celebrities have spoken out. Every year in Los Angeles, Farrell hosts an awards ceremony to honor abolitionists, among others. Kiefer Sutherland, Mario Cuomo, George Ryan, Danny Glover, the cast of The West Wing, and the cast of The Practice have all been honored at the event. “It used to be taboo to bring the death penalty up in polite company,” said Farrell. “We’ve created a safe environment to oppose it publicly.” Farrell, who donates a large undisclosed sum every year to Death Penalty Focus, flew in from L.A. for both the Allen and Williams executions to make speeches, as he always has. “Once you see the horrors of the justice system,” he told me, “it’s hard not to oppose it.” Stars were so common, it wasn’t surprising to be sipping tea with Joan Baez the day of Williams’s death. Wearing wooden prayer beads on her wrist and the tags of a Marine who had served in Iraq around her neck, Baez commented that the Save Tookie rally would be her first protest at San Quentin in 20 years. “We’re finally starting to win,” said Baez. “I think they’re finally starting to listen.” It was difficult not to agree with her that day. On a national level, celebrities may do more harm than good for the anti–death penalty issue. These days, all a conservative has to say is “Hollywood liberal” to turn middle America against a cause. But in California, let’s be honest, they wield serious clout. Remember who our governor is. MARCH 2006 SAN FRANCISCO D I N O VO U R NAS/AP “There are three reasons politicians support the death penalty,” Farrell told attendees at a private brunch in Sausalito. “Politics, politics, politics.” anti voices, the blogosphere exploded with surprising anti–death penalty opinions, including some from hardcore conservatives. “As Abraham Lincoln said when pardoning a deserter in the Civil War,” wrote Andy Nevis, a prolific conservative blogger who is only 15, “he will be of more use above ground than below it.” South African archbishop Desmond Tutu and former Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev also favored clemency, and when Schwarzenegger refused to grant it, politicians in his hometown of Graz threatened to remove his name from their stadium. (He beat them to the punch, ordering them to remove his name immediately.) Williams’s 10 anti-gang books and five Nobel Peace Prize nominations had a lot to do with the explosion of protest. But, as with most media events, the celebrities were key. Jamie Foxx started the domino effect, playing Williams in Redemption: The Stan Tookie Williams Story, a film that aired on national television in 2004. In the month before Williams’s execution, it seemed nearly impossible to rent Redemption at local video stores. Foxx reeled Long Beach rapper Snoop Dogg into the campaign by inviting him to a screening of the film. On a sunny morning in November, about a thousand death penalty foes, Williams supporters, hip-hop fans, and journalists had gathered on the waterfront by the prison to hear Snoop. Dressed in an oversize Save Tookie.org T-shirt and black jeans, the rapper walked onto the stage flanked by black-clad bodyguards. The crowd roared. “I want to say to you, Governor, that Stanley Tookie Williams is not just a regular old guy,” he said, his cornrows looking a bit fuzzy that morning. “He’s an inspirator. He inspires me, and I know I inspire millions...So you add that up. That’s over a hundred million people that’s inspired by what he’s doing.” Snoop’s speech lasted all of three minutes, and it wasn’t primarily about abolishing the death penalty. But he made a good point. Through the multiple cameras filming, he was indeed reaching millions; arguably, by Snoop’s mere presence, and his chant of “Change gonna come!,” a new generation was being eased into the abolition fold. One evening, as Williams’s death grew closer, actor Danny Glover showed up fashionably late to a Redemption screening in the Mission district. Glover said he thought there was a chance that Schwarzenegger might spare Williams. Oakland hip-hop star Boots Riley of the Coup and filmmaker Kevin Epps (Straight Outta Hunters Point), jumped in, too. “Tookie’s words, man, they’re like 2Pac,” said Epps, shedding tears. “We gotta save this cat.” True, the stars were more focused on saving Williams than on death penalty abolition—and some of their comments probably wouldn’t have found favor with the governor. Snoop recalled his early days as a member of the Crips gang, and Riley, in an otherwise intriguing analysis of poverty and violence, joked that you can’t sue the guy who steals your weed. But mixed in with so many activists giving abolition speeches, the two causes became virtually synonymous. Some of the stars were doing more than just talking. A few days before Williams’s death, I found myself at an 138 “We claim to be killing in the service of victims’ families now,” Zimring said. “But that can only last so long.” The new rationale gained popularity nationwide and executions increased, especially in the South, where 81 percent have occurred since 1977. Killing in the name of closure is illogical when we execute so few. California averages 2,400 homicide convictions per year, and we execute less than a handful of the convicted murderers. What about closure for the other 2,395 families? But the argument is emotionally effective, and the media has gone along: in a database search, Zimring found that the number of news stories mentioning closure went from almost none in the mid1980s to more than 400 in 2001. Even the Chronicle, reporting in a city where the majority of citizens oppose the death penalty, sometimes covers the victims’ families more than the execution. By 1999, the peak year of U.S. executions, it seemed the nation was going to take the killing spree into the new millennium. Only China, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were executing more regularly than the southern United States. But there was a backlash. DNA testing became mainstream and a host of death row inmates were found to be innocent. About 122 death row prisoners have been exonerated to date, six of them in California. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to execute minors and the mentally retarded. Illinois implemented a moratorium, and New York’s highest court declared executions unconstitutional. Only months ago, New Jersey joined the moratorium states. Zimring sees all this as part of a historic march: first, executions cease to be viewed as important to crime control, which leads to a slowing down. Then, usually during a shift to the left in the government, the death penalty gets abolished. The first states abolished it in the mid–19th century after scholars began questioning its value. (Currently, 12 states, plus the District of These days, all a conservative has to say is “Hollywood liberal” to turn middle America against a cause. But in California, let’s be honest, celebrities wield serious clout. The night of Clarence Ray Allen’s execution, protesters ranged from famous to fringe, with everyday Bay Area residents in between. JAI MAL YO G I S SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 because almost everyone now realizes that the death penalty does not serve what many would see as its primary purpose: preventing murders. “It doesn’t,” Zimring told me. “It is brutally useless.” And the statistics are there to prove it. Zimring says none of the European countries or U.S. states that have abolished capital punishment have seen a rise in homicides. After abolition, Canada actually saw a 23 percent reduction in murders. The New York Times conducted a study in 2000 and found no evidence that the death penalty served as a deterrent. To be fair, several journals have published studies showing contrary evidence, but so many scholars have criticized the authors’ statistical methods that the results seem unreliable. So why do we still have a death penalty, especially when the rest of the developed Western world has already abandoned it? The last person in western Europe to be executed—perhaps forever—was a Tunisian immigrant convicted of rape and murder. He was beheaded in Marseilles in 1977. Beginning with Italy in 1944, western Europe began abolishing capital punishment; France, in 1981, was the last to do so. Countries that execute cannot even join the European Union. The strange thing is that in 1977 the United States was in a similar moral space as Europe and could have gone the same way. While France executed two people in 1977, the United States executed only one; in 1972 the Supreme Court had ruled all existing state capitalpunishment systems unconstitutional. But four years later, in Gregg v. Georgia, the court reversed course, allowing states to execute provided they complied with new standards. Most states eventually brought back what Zimring terms a “reinvented death penalty.” Instead of claiming that executions would protect people from more homicides, increasingly prosecutors and politicians shifted the rhetoric, portraying the penalty as a sort of community effort to create “closure.” Columbia, have no death penalty law on the books.) “There are a lot of things people disagree on about the death penalty,” Zimring said. “But there is one thing that everyone agrees on, and that’s that we don’t need a death penalty. That’s why you didn’t hear Schwarzenegger arguing that killing Tookie would keep murders down.” 140 SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 Junior Page .66 The lack of a concrete need for capital punishment has gradually pushed the debate back into mainstream politics in California. Sally Lieber, a Democratic assemblywoman from Silicon Valley, cointroduced AB 1121 last year to put a hold on executions until 2007. She supports capital punishment but doesn’t want the state rushing into any unjust executions. The bill had support from at least 30 members of the 80-member assembly, along with 40 high-profile California judges, police officers, and prosecutors. It died in January before getting to a vote, but supporters plan to reintroduce it in the senate, where it has a better chance of passing. The day after the moratorium passed its first hearing in Sacramento, I met Stefanie Faucher, program director of Death Penalty Focus. The 26-year-old redhead is one of a growing band of people who combat executions full-time as paid staffers in the Bay Area for Death Penalty Focus, the ACLU, and Amnesty International. “It’s a great first step,” said Faucher, positively bubbly. “You’ve seen this in New York and Illinois. The majority of people support the death penalty until they really see the facts.” Although Death Penalty Focus is the strongest voice in California’s abolition movement, its eighth-floor office in the Flood Building on Market Street is cramped and suffers from ugly gray carpeting. “But with a $400,000 annual budget, you work with what you have,” said Faucher, who talks like a lawyer but isn’t. She works alongside Executive Director Lance Lindsey. The day we met, Lindsey’s eyes were heavy under his round glasses. He had been protesting Clarence Ray Allen’s execution at San Quentin until 3 a.m. and woke up at 5 a.m. for a New York radio interview. For much of Lindsey’s 10 years with the organization, the movement felt like a street corner operation. Now Lindsey and Faucher, like Minsker—who became the ACLU’s first full-time anti–death penalty advocate in 10 years—meet regularly with policy makers. “Politicians were afraid to be seen in the hall with us,” said Lindsey, who had worked as a school principal and for the Special Olympics before becoming a full-time abolitionist. “I saw it as the culmination of every social justice movement. Civil rights, segregation, it all came together in this fundamental injustice. But it was such a fringe issue.” The majority of Californians want a moratorium. The problem is, most politicians outside the Bay Area are afraid to pass it. “They’re afraid of being called soft on crime,” says San Francisco assemblyman Mark Leno, also a coauthor of the bill. Republicans have tried to characterize the moratorium essentially as death penalty abolition even though many death penalty advocates see a thoughtful pause as necessary to fix flaws in the system. “If the prosecution is going to have the moral authority to request the death penalty,” says Ira Reiner, former district attorney of Los Angeles and a firm supporter of capital punishment, “we need to be constantly vigilant in improving the system. If it came to a point where we could not be virtually certain that innocent people are not being killed, that might be enough for one to make a moral switch to oppose the death penalty.” 142 SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 Junior Page .66 A new group of 14 experts is in charge of making sure California is not on track to kill an innocent person. The California Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice is a bipartisan committee created by the San Francisco power-legislator John Burton in 2004 just before he termed out in the senate. Think of it as a 9/11 commission for criminal justice: the committee will research specific cases, interview witnesses and experts, and every few months issue recommendations. In December 2007, it will publish a final report. The abolitionists’ fantasy is built around this commission because they saw what massive changes a similar group catalyzed in Illinois. After exonerating 13 death row inmates in a short time, Illinois put a twoyear moratorium on the death penalty so the commission could study the system, much like California is trying to do now. The commission, which included the famous crime novelist and former prosecutor Scott Turow, came out with 85 recommendations for the system. Then-governor George Ryan reviewed the findings and every single death row case, and to the nation’s shock, commuted 167 death sentences and pardoned four inmates entirely. In a speech, Ryan said, “I cannot support a 144 SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 Junior Page .66 system, which, in its very administration, has proven to be so fraught with error and has come so close to the ultimate nightmare, the state’s taking of an innocent life.” Judging by the California commission’s bipartisan demographic, it’s hard to guess what conclusions it will draw. At least five members are associated with law enforcement or prosecution, including the district attorney of San Mateo County, James Fox, who has sent 20 criminals to death row since 1983. And at least four others have criminal-defense backgrounds, like Michael Laurence, the executive director of the Habeas Corpus Resource Center in San Francisco. Jon Streeter, a former defense attorney who is the vice-chair of the commission, told me he won’t make any predictions except one: that the final results will make a big splash and possibly change the death penalty’s status forever. “Looking at the procedural problems and exonerations, we could ultimately conclude that we should reform our death penalty laws,” he said. Numerous studies already suggest that the commission will find many of the same flaws that made Ryan reverse course. According to a study by the Los Angeles Times, the death penalty costs California taxpayers $114 million more per year than life without parole would cost. But the arbitrariness of the system is far more shocking. The application of the death penalty in California varies widely from county to county: murder someone in Riverside County, which has sent 54 people to death row since 1977, and you are many times more likely to get a death sentence than if you murder someone in San Francisco. Those who murder whites are over four times more likely to get death than those who kill Latinos and over three times more likely to get death than those who kill African Americans. One of the most talked-about studies, published in the Santa Clara Law Review in 2003, analyzed how many of the 85 Illinois recommendations California’s system met. Only five, the study found. Many attorneys have told me that poor criminal defense in capital cases is a huge problem. “One of the main reasons California has such a large death row is a lack of qualified defense,” said Laurence, who is on the commission. California only recently created minimum standards for capital defense attorneys, some of whom have shown themselves to be less than professional at times. One court-appointed defense attorney in San Bernardino County regularly came to a death penalty trial drunk and was arrested for driving to the courthouse with a .27 percent bloodalcohol content. This is not to say that California does not have many deft defense attorneys. But to see that there is a serious problem, you don’t even have to look to the most egregious cases. Take Allen’s capital trial: while the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ultimately didn’t reverse his death sentence, the justices noted that his defense was so poor that it “fell below an objective standard of reasonableness.” The court said Allen’s court-appointed counsel admitted to doing nothing to prepare for the penalty phase of the trial until after the guilty verdicts were rendered. Such unfairness in how the death penalty is applied has allowed some politicians to feel safe in opposing it. But a new infusion of religious support for abolition could end up casting an even wider safety net. The Catholic Church has long opposed the death penalty in a quiet way, but recently the church has made it a forefront issue in its “Culture of Life” campaign, which includes opposition to abortion and euthanasia. It even changed the official catechism to reflect its opposition. Simultaneously, Catholics’ support for the death penalty went from 68 percent in 2001 to 48 percent in 2004. California is 25 percent Catholic. That figure is growing, and the state senate has a large Latino caucus. (Schwarzenegger is Catholic, but it’s tough to know if his faith influences his political decisions.) Few religious institutions are as centralized as the Catholic Church, but adherents of many other faiths and sects are taking a stand against the death penalty. I met Muslims, born-again Christians, Episcopalians, Baptists, Buddhists, Quakers, and Jews protesting the death penalty at San Quentin. And at a pro-moratorium rally in front of City Hall in November, just about every other speaker was preaching. Rabbi Alan Lew of Congregation Beth Sholom in San Francisco delivered a thunderevoking speech: “A million years may pass, but killing will never bring peace,” said Lew. “It is a spiritual impossibility, an immutable law.” Catholic bishop John Wester followed with a message from Catholic bishops across the state: “We implore all Californians to ask what good comes of state-sanctioned killing?” Even the political speakers were getting biblical. “What would Jesus do?” asked Supervisor Tom Ammiano. “He’d kick your sorry butt out of the temple, Mr. Bush.” To understand the Catholic viewpoint, I met up with George Wesolek, director of public policy and social concerns for the Archdiocese of San Francisco. A jolly, bald man who wore a red sweater, Wesolek said he has seen a small group of lapsed Catholics return to the church because they strongly oppose the death penalty. The death penalty debate has fluctuated for centuries within the Church, Wesolek said. But with the ability to lock people up for life and even deny them access to other prisoners and visitors if necessary, the Pope says capital punishment is out of the question for modern societies. The Old Testament prescribes death for no fewer than 36 crimes, including practicing witchcraft, working on the Sabbath, and talking back to your parents. And in the biblical story, God does kill wrongdoers. But he also spares them: David, for instance, and even Cain, the king of all murderers, receive pardons from God. This contributes to the Catholic belief that God prefers forgiveness. But the main reason for Catholics’ opposition is Jesus. “Jesus is the fulfillment of the law,” Wesolek said. “Jesus comes in and says, ‘Actually the whole law is to forgive; the whole law is love; the whole law is service.’” And recall that in John 8:1–11, it’s Jesus who saves an adulterous woman from being stoned, warning an angry crowd: “He that is without sin among you, let him cast a first stone.” It’s understandable that some people, even after learning the impracticalities of the death penalty and knowing that even God may oppose it, still want murderers to die. Who hasn’t at times wished death on the sickest killers and rapists? As former district attorney Reiner told me: “Even if the death penalty has no deterrent effect, the reason to support it is a moral one: there are cases where the punishment fits the crime.” Perhaps. Or perhaps Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Mother Teresa were right in opposing the death penalty. The moral debate will go on as long as people commit murders. But aside from whether the death penalty is right or wrong, few can reconcile themselves with the horror of executing an innocent person. Through all my discussions, that issue kept resurfacing, and many experts say California is dangerously close. That scenario has already befallen other states. Georgia recently apologized for executing an innocent woman, Lena Baker, more than 60 years ago. Last year a Texas judge and prosecutor reportedly admitted to wrongfully executing the innocent Ruben Cantu in 1993. Zimring estimates that as many as seven innocents have been killed in the U.S. already. Even if prosecutors, judges, and jurors got it right 99 percent of the time, six or seven innocent people are currently waiting 15 years in a cell for California to poison them. Toward the end of my interview with Heller, after he had talked extensively about the immorality of Tommy Thompson’s execution, I asked him what it would take for the law he wrote to be undone. Would the activists, preachers, and Bay Area politicians have enough impact to change the hearts and minds of a good chunk of the state’s population? Heller paused, as if he were pondering an obscure bit of constitutional law. “At some point in the future, there will be no death penalty,” he said. “But I think it will happen when we know for certain that someone innocent has been killed. I mean know for sure—DNA, everything.” In the meantime, as Heller regrets the day he wrote California’s death penalty law, he will continue to remind voters that only they have the power to vote it out. ■ “You’ve seen this in New York and Illinois. The majority of people support the death penalty until they see the facts.” Half Page Vertical .5 147 146 MARCH 2006 SAN FRANCISCO Allen’s grandnephew holds a family photo taken just hours before his uncle’s execution. The nephew said he felt sorrow for the victims’ families. JAI MAL YO G I S SAN FRANCISCO MARCH 2006 JAIMAL YOGIS IS SAN FRANCISCO’S WRITER-REPORTER. ADDITIONAL REPORTING BY CHRIS SMITH AND LEIGH FERRARA.