Feature-Environment-From-Cradle-To-Grave-Life

advertisement

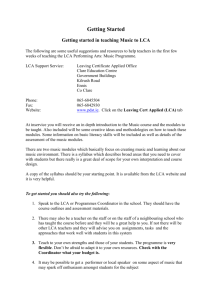

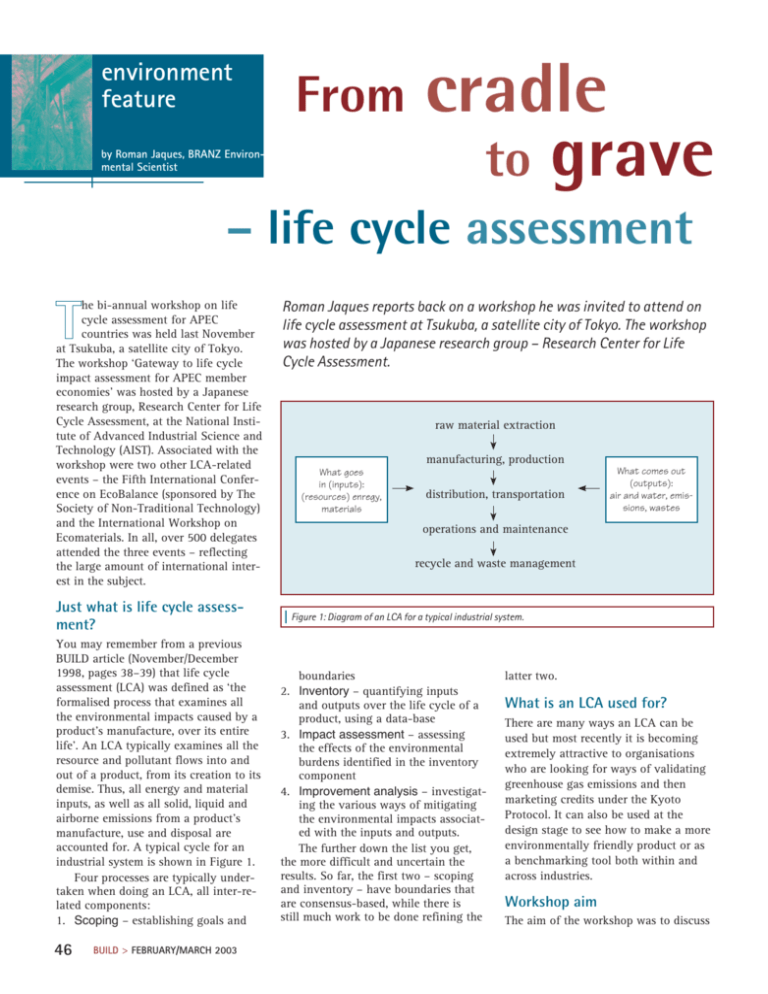

environment feature From by Roman Jaques, BRANZ Environmental Scientist cradle to grave – life cycle assessment he bi-annual workshop on life cycle assessment for APEC countries was held last November at Tsukuba, a satellite city of Tokyo. The workshop ‘Gateway to life cycle impact assessment for APEC member economies’ was hosted by a Japanese research group, Research Center for Life Cycle Assessment, at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST). Associated with the workshop were two other LCA-related events – the Fifth International Conference on EcoBalance (sponsored by The Society of Non-Traditional Technology) and the International Workshop on Ecomaterials. In all, over 500 delegates attended the three events – reflecting the large amount of international interest in the subject. Just what is life cycle assessment? You may remember from a previous BUILD article (November/December 1998, pages 38–39) that life cycle assessment (LCA) was defined as ‘the formalised process that examines all the environmental impacts caused by a product’s manufacture, over its entire life’. An LCA typically examines all the resource and pollutant flows into and out of a product, from its creation to its demise. Thus, all energy and material inputs, as well as all solid, liquid and airborne emissions from a product’s manufacture, use and disposal are accounted for. A typical cycle for an industrial system is shown in Figure 1. Four processes are typically undertaken when doing an LCA, all inter-related components: 1. Scoping – establishing goals and 46 BUILD > FEBRUARY/MARCH 2003 Roman Jaques reports back on a workshop he was invited to attend on life cycle assessment at Tsukuba, a satellite city of Tokyo. The workshop was hosted by a Japanese research group – Research Center for Life Cycle Assessment. raw material extraction What goes in (inputs): (resources) enregy, materials manufacturing, production distribution, transportation What comes out (outputs): air and water, emissions, wastes operations and maintenance recycle and waste management Figure 1: Diagram of an LCA for a typical industrial system. boundaries 2. Inventory – quantifying inputs and outputs over the life cycle of a product, using a data-base 3. Impact assessment – assessing the effects of the environmental burdens identified in the inventory component 4. Improvement analysis – investigating the various ways of mitigating the environmental impacts associated with the inputs and outputs. The further down the list you get, the more difficult and uncertain the results. So far, the first two – scoping and inventory – have boundaries that are consensus-based, while there is still much work to be done refining the latter two. What is an LCA used for? There are many ways an LCA can be used but most recently it is becoming extremely attractive to organisations who are looking for ways of validating greenhouse gas emissions and then marketing credits under the Kyoto Protocol. It can also be used at the design stage to see how to make a more environmentally friendly product or as a benchmarking tool both within and across industries. Workshop aim The aim of the workshop was to discuss and prioritise environmental issues for different APEC economies, and to examine how the latest impact assessment models relate to these priorities. For example, in what ways were the different environmental impacts – such as depletion of the ozone layer, land use, soil quality and human toxicology – modelled, measured and addressed? There was also much discussion on what the key characteristics of a good LCA should be. At the core of this is the question ‘how can an LCA best serve the needs of people and the environment in the future?’ It was suggested that in essence, an LCA tool should be ‘as simple as possible and as complex as required’, given that a tool’s complexity doesn’t guarantee more accuracy in the overall assessment. Also, although the theory and social and environmental science behind the tool can be very complex, to ensure its use its application and interpretation should be very simple. New issues The other two LCA events held concurrently focused on new methodological issues of LCA, such as statistical analysis, social aspects and new environmental impact categories to consider. Sensitivity analysis in inventory and valuation process of impact assessment will continue to be discussed in more depth. In addition, reports on various users and uses of LCA as a practical tool were given, for example, as a decision support tool, for resource allocation, environmental auditing, quality improvement, and comparison of alternative processes. Key messages for delegates Delegates took home several messages from the proceedings: • there needs to be more sharing of LCA experiences and data, both within industry and between nations developing tools • there needs to be a build-up of local capacity in countries, in terms of training and education in the uses of these types of tools • users of LCA tools are now becoming more interested in ‘other’ environmental impact categories, in addition to the usual energy and CO2 emissions • the recognition that the global driving force of LCA tools is from waste management and building material assessment. • the speed of progress within the field of LCA is making it difficult to keep up. Overall, there was agreement that there were many new exiting approaches to LCA internationally, with some very promising developments. The gap between LCA theory and its practical application is rapidly reducing as more tools are used and refined. The title for the Fifth International Conference on EcoBalance conference – ‘practical tools and thoughtful principles for sustainability’ – applied equally well to the LCA workshop. Roman Jaques would like to thank AIST for the opportunity to participate in the AIST–APEC workshop. BUILD > FEBRUARY/MARCH 2003 47