Perspectives on Psychological

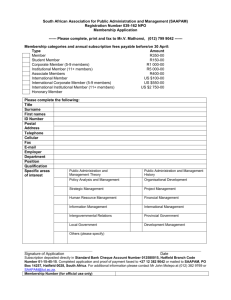

advertisement