2014 Impact Report - The Nature Conservancy

advertisement

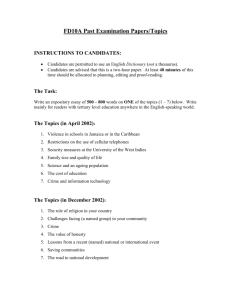

Caribbean The Program 2014 Impact Report From the Caribbean Program Director I’m proud to present in this report the many accomplishments of The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Program between July 2013 and June 2014. This has been a year of tremendous impacts as we seek to protect and restore our seas and reefs and create a more sustainable future for the people who live in this special region. After eight incredible years at the helm of the Program, I will be transitioning to the Conservancy’s Global Marine Team to help grow our global coral reef conservation vision. The need to protect and restore reefs has never been greater than it is today. I want to thank the many volunteers and philanthropic leaders who have invested in us so generously over the years. Our successes would not be possible without these visionary partners and their confidence in our mission. Thank you again for your help in making our efforts to protect the Caribbean a reality. Dr. Philip Kramer From the Caribbean Board Chair In 2014, I’ve been inspired not only by the tremendous work of The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Program staff, but also by all of the people with whom our program engages. Our work with nearly 900 volunteers this year exemplifies our deepening collaboration with communities. Our efforts to build a stronger constituency for conservation include these local volunteers as well as fishers, government officials, business owners and many others who are making transformational changes to build a sustainable future for the region. I am personally inspired by Martin Barriteau, Executive Director of our partner Sustainable Grenadines, whom I met this April and who has been working side by side with us to assure that the government and the private sector are engaged with our mission. Without dedicated islanders, achieving our goals would become much more difficult. Thanks to all of you for your support. Susan H. Smith Fishermen off the waters of in Île à Vache, Haiti © Tim Calver; Inset top Dr. Philip Kramer © Chris Crisman; Inset Bottom Susan Smith © Victor Capellan Cover Stephanie Placide, student participant in a Conservancy-supported sustainable agriculture project in Île à Vache, Haiti © Tim Calver This page 2 Caribbean Program 2014 Impact Report Finally, I’d like to express my sincere gratitude to Phil Kramer for his years of dedication leading the Caribbean Program. He’s grown the program tremendously, and we look forward to building on the significant advances made during his tenure. By the numbers 893 Protecting the Caribbean I m pacts by th e Ca r i b b e a n P r o g r a m ov e r th e pa st ye a r Caribbean governments support the Caribbean Challenge Initiative (CCI) to protect 20% of nearshore marine and coastal environments by 2020* 10 402,880 5,000 247,126 20 Million 10% $8 Million 150,908 16,000 conservation volunteers trained in Haiti, U.S. Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Grenada, Dominican Republic and The Bahamas corals out-planted to-date trees planted in the Dominican Republic and Haiti added to Caribbean Biodiversity Fund of $37 million total raised to date acre shark sanctuary declared in British Virgin Islands through CCI support mangroves planted in Haiti, The Bahamas and Grenada acres of new marine parks declared in Haiti of nearshore marine and coastal environments protected to date corals growing in nurseries *CCI Signatories: The Bahamas, British Virgin Islands, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, U.S. Virgin Islands. Protecting the Seas Making History in Haiti This May along the northern coast of Haiti, underwater explorers reported the discovery of what may be the wreckage of Christopher Columbus’s ship the Santa Maria, which sank there more than 500 years ago. At the same time in waters very close by, Conservancy scientists were carrying out their own exploration—of the reefs and mangrove stands that make up the newly declared Three Bays National Park. Since Columbus’s arrival, Haiti has been a complicated landscape both politically and ecologically. And while economic and social recovery after the 2010 earthquake remains halting, the past year has seen signs of hope for the Haitian environment as Haiti has established six national marine parks, including its first ever. Three Bays National Park covers approximately 187,000 acres. The Conservancy’s research in these waters several years ago helped characterize their diversity, and the Conservancy is playing a critical role in setting up the park. To fulfill its promise of protecting and restoring marine habitats, Three Bays needs a strong, sciencebased management plan and effective ways to monitor progress. The surveys conducted this spring using satellite imagery, boats, underwater cameras, snorkelers and even a drone (see Page 10) are aimed at informing the design of these management and monitoring plans. Equally important for Three Bays is engagement with local communities—especially fishers and others who make their living from the land and sea—to help them adopt more sustainable fishing practices and to develop alternative income sources. The Conservancy is also working to encourage the Haitian government to join the Caribbean Challenge Initiative this coming year. Although there is a long road ahead for conservation in Haiti, the progress of the past year is inspiring hope. Maxene Atis The Nature Conservancy’s Haiti Conservation Coordinator Maxene was born in northwestern Haiti, studied geology in Port au Prince, and did development work for the United Nations before studying business in Florida. He sees his work for the Conservancy as a fitting combination of his science, development and business backgrounds. “Our job is not just nature or the ecosystems or the mangroves or the fish, but it’s also the people living around us,” says Maxene. “It’s a reality now for Haiti that conservation and livelihood work hand in hand, and you can’t be successful in conservation if you don’t take into account the livelihoods of people.” Despite the challenges of working in Haiti, Maxene is optimistic about the future of conservation there: “Seeing resolve on the government side gives me hope for the future of Haiti.” “Our job is not just nature or the ecosystems or the mangroves or the fish, but it’s also the people living around us.” — Maxene Atis Atis © Tim Calver opposite page Left to right Rock beauty fish (Holacanthus tricolor) in the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park in The Bahamas © Jeff Yonover; Upside-down Jellyfish (Cassiopeia xamachana), found in The Bahamas and throughout the Caribbean © Tim Calver tHis page Maxene 4 Caribbean Program 2014 Impact Report Catalyzing Region-Wide Solutions Launched in 2008 with The Nature Conservancy’s support, the Caribbean Challenge Initiative (CCI) is inspiring Caribbean nations and territories to conserve at least 20 percent of their marine environment by 2020 and create trust funds to generate long-term funding to support park management. To date, 10 governments have signed onto the CCI, and The Bahamas has become the first to pass legislation to establish its national conservation trust fund. This milestone means that Bahamian marine parks will have a dedicated source of revenue to employ staff, galvanize local community support, purchase equipment, build visitor facilities and monitor ecosystem health. The new trust fund—the Bahamas Protected Areas Fund (BPAF)—was designed with the help of Conservancy staff and established through legislation adopted by the Bahamian Parliament. The Bahamas Government has allocated $2 million to BPAF in this year’s budget. The BPAF will also receive annual payments in perpetuity from a regional trust fund called the Caribbean Biodiversity Fund (CBF). The CBF is establishing a $42 million permanent endowment to support commitments under the CCI and is funded by the German Government, World Bank/Global Environment Facility and the Conservancy. In May 2014, the World Bank contributed $7.2 million, which marked a significant milestone and vote of confidence in the ability of the CBF to serve as a regional conservation solution. Public and private investors are united in their recognition of the importance of the CBF to generate permanent revenue streams for marine conservation. The CBF and national trust funds remain a top priority of the Conservancy’s Caribbean Program as we work to help put the Caribbean on a path to a sustainable future. “Despite the challenges of climate change and ocean acidification, marine protected areas can improve the health of coral reefs.” — Dr. Robert Steneck, University of Maine School of Marine Sciences, Conservancy Caribbean Trustee 5 Restoring Coral Reefs Real Impacts From Coral Nurseries In the past year, the number of corals growing in nurseries has tripled from less than 5,000 to more than 16,000, In the clear turquoise waters off the and the number of nursery-grown corals southwest coast of New Providence island in out-planted on reefs has doubled to 5,000. The Bahamas, an array of strange structures rises from the sandy bottom. It may look “We are rapidly approaching the scale and like a grove of underwater Christmas trees, success rate needed to make significant but this is a coral nursery—one of 10 set up ecological impacts,” says Kemit-Amon by The Nature Conservancy and partners Lewis, the Conservancy’s Caribbean over the past five years in The Bahamas and Coral Conservation Manager. Restored U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). These nurseries reefs will become home to economically have become the source of amazing and and ecologically important fish species, unprecedented coral-restoration success. attractions for divers and part of healthier, more resilient reefs. The idea of coral restoration is relatively simple. Scientists use SCUBA to collect The success of coral restoration in the broken fragments of elkhorn and staghorn USVI and The Bahamas is being used coral after reef-damaging storms. Most as a model throughout the Caribbean, of these fragments would die once broken where the degraded state of many reefs from the reef, but the collected fragments makes restoration a critical complement are brought back to nurseries, multiplied to the establishment of protected areas. (by breaking them into smaller pieces) As the forests of coral trees grow, so does and allowed to grow, hanging from PVC hope for the renewal of coral reef health trees to form large arrays with many coral across the region. “ornaments” strung from each branch. When the fragments grow big enough, they are returned to Caribbean coral reefs produce $2.7 billion reefs to speed regrowth. Training Master Coral Gardeners With the growth of coral-restoration efforts in the USVI and The Bahamas, the Conservancy has an increasing need for divers who can help maintain and monitor the coral nurseries and support out-planting efforts. To mobilize volunteer divers, Conservancy staff have designed a new specialty course to train recreational divers in coral restoration. The course, certified by the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), is already being offered at Stuart Cove’s Dive Resort in The Bahamas, where Conservancy staff have trained local dive shop staff to teach the class and lead volunteer maintenance and monitoring dives. The course will soon be offered on St. Croix and St. Thomas, in the USVI. The expanding cadre of coral gardeners not only increases the capacity to restore reefs, but also educates divers, both local and visiting, about the importance of reefs and reef restoration. in economic benefits from tourism and $395 million from fisheries each year. — World Resources Institute 6 Caribbean Program 2014 Impact Report tHis page Left to right Staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornus) outplants in the U.S. Virgin Islands © Kemit-Amon Lewis/TNC; Volunteer divers at a coral cleaning demonstration in The Bahamas © Eddy Raphael/TNC Emmalin Pierre Parliamentary Representative for St. Andrew South East Constituency, Grenada Climate Resilience for Island Communities Small island states like Grenada do not have the luxury of time in responding to climate change and sea-level rise. Grenville, on the island’s east coast, already faces serious flooding and erosion from the one-two punch of degraded reefs and coastal storms, and the town’s most severely affected neighborhoods are also some of its poorest. This year, The Nature Conservancy began working with local officials and community members in Grenville on an innovative engineering project that could become a model for protecting small islands from the impacts of climate change. The idea is to test several steel, rock and concrete structures to reduce the water flow and wave energy that reaches the shoreline. The structures are designed to allow coralline algae and corals to grow over them, and to encourage this regrowth, the Conservancy will also establish a coral nursery. If the pilot structures are successful, the plan is to construct a larger array with the help of community members. Emmalin Pierre is a member of Grenada’s Parliament whose constituency is inextricably linked to the sea. “Up and down this sea coast are villages where the men and women rely heavily on the ocean and its resources for their livelihoods,” she says. “For generations they have provided for themselves through the sustainable use of marine resources.” Coral reefs play a critical role in these communities—by reducing wave intensity and erosion and providing the resources they depend on to make a living. “We are concerned about the environment,” says Pierre, “but we also support work to protect the reefs because by doing so we are protecting the homes and livelihoods of those who live in our coastal areas.” This project is in its early stages, but Conservancy staff are excited about the potential to develop low cost and environmentally friendly alternatives for small islands that will provide protection from the unrelenting waves of the Atlantic Ocean. “In the case of the people I represent, these reefs are also extremely important for protecting their homes and livelihoods.” — Emmalin Pierre tHis page Left to Right Children in Grenville, Grenada © Shawn Margles/TNC; Shoreline erosion in Grenville, Grenada © Shawn Margles/TNC; Emmalin Pierre © St. Andrew South East Constituency 7 Doña Pirigua Trustee for The Nature Conservancy in the Caribbean Rosa Margarita Bonetti de Santana, better known as Doña Pirigua, is a member of the Conservancy’s Caribbean Board of Trustees and the President of Fundación Propagas, a corporate foundation in the Dominican Republic whose goal is to inform the public about the environment through educational and sociocultural programs. Doña Pirigua believes that private industry should have a role in Caribbean conservation. “Philanthropy and corporate social responsibility help compensate for the private sector’s ecological footprint,” she says. “It should work with the state to promote biodiversity conservation, poverty alleviation, public education and national development.” As a native of Santo Domingo, Doña Pirigua is inspired by and a supporter of the formation of the Dominican Republic’s new water funds, which she says will “help ensure the long-term quality and quantity of the water supply. Conservation and restoration activities will improve the health of rivers, increase vegetation coverage and provide water as a source of life.” With regards to a sustainable future for the Dominican Republic, Doña Pirigua envisions “a new development model that is socially just and ecologically balanced. The more people who join this cause, the more quickly we will advance.” People and Nature Protecting Freshwater in the Dominican Republic People in many Caribbean island nations have limited freshwater, and this scarce resource is further stressed by agricultural and urban uses. In the Dominican Republic, The Nature Conservancy is introducing water funds, tools that are being applied for the first time on a Caribbean island to conserve watershed-wide freshwater. Water funds provide a way for the cities, industries and individuals who rely on freshwater to invest in sustaining it. Water users contribute to the funds in exchange for the water they consume. Users may range from municipal water systems to farmers and ranchers to factories or other industry. After many years of work in the country, 2013 saw the formation of two funds in the Dominican Republic. One supports the three watersheds that supply water to the nation’s capital, Santo Domingo. The other focuses on the largest river system in the Dominican Republic, the Yaque del Norte. Together these watersheds supply water to 60 percent of the country’s population. As part of the Latin America Water Funds Partnership, Conservancy staff in the Dominican Republic worked with local partners and government institutions to help design the water funds. Water fund revenues can be channeled to existing reforestation work, as well as to improving management of established national parks within the affected watersheds. Revenues can also go to highland communities who institute conservation measures. Protection of water sources through the water funds will reduce the impact of dry periods on farmers and improve the health of downstream ecosystems—all while helping to provide sustainable freshwater for the people who live in cities and towns throughout the watersheds. The Conservancy’s $1.7 million investment in two transformational water funds in the Dominican Republic will support watersheds that serve 60 percent of the country’s population. 8 Caribbean Program 2014 Impact Report See Food Sustainably The Nature Conservancy and partners have launched a new sustainable seafood program on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Reef Responsible Sustainable Seafood Initiative provides training and educational materials about sustainability and fishing practices for restaurant owners, fishers and the wider community. The program also includes a certification component—local restaurants can sign on and implement sustainable sourcing for the seafood they serve and in return receive branding and promotion as “Reef Responsible.” This program will promote sustainable seafood and reduce overfishing and harmful fishing practices—leading to healthier reefs while preserving the future of fishing communities through sustainable harvesting. The Conservancy is supporting mangrove restoration efforts, with Île à Vache residents planting 150,000 seedlings this past year alone. The Conservancy is also introducing local people to sustainable farming methods that help reduce the erosion of soil into coastal waters and provide alternative food sources to take pressure off of fish populations. The Conservancy and partners inaugurated an agricultural demonstration site in May that will serve as a model of techniques for residents to use on their own properties, and the profits from vegetables being sold there are going back to support island conservation efforts. Restoring Haiti’s South Coast Île à Vache, or “Cow Island,” in Haiti, served as the operations base for the pirate Captain Morgan in the 17th century. Today, this small, 20-square-mile island is home to 14,000 people and is struggling to support its three primary sources of livelihood—fishing, farming and tourism. The harvesting of mangroves on the island has left the coast more vulnerable to flooding and has led to a decline in fish populations. fishermen prepare nets © Tim Calver; Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans) seedling © Tim Calver; Elina Mathurin with mangrove seedlings she’s growing for coastline restoration in Île à Vache, Haiti © Tim Calver opposite page Haina-Duey watershed, which provides water to the city of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic © Erick Conde/TNC; Inset Doña Pirigua © Rubén Román tHis page Caribbean 9 It’s a Bird, it’s a Drone—it’s Henri! By Dr. Steve Schill, Caribbean Program Senior Scientist The small, agile quadcopter touched down and landed softly on the water. It took off again, circled 250 feet above us and smoothly drifted through the air along a preprogrammed path. The local Haitian fishers looked up and stared in awe at this strange new flying machine. They are not alone in their fascination with drones, which have recently gained press attention for uses ranging from military operations to Amazon home delivery. So far, most uses in conservation have focused on monitoring poaching and counting wildlife. As a mapping technology nerd, I have been following these developments with the aim of building a drone to map marine habitats for The Nature Conservancy’s Caribbean Program. My opportunity arrived when Jordan Mitchell, one of the students in a remote sensing class I teach, showed an uncanny skill for drone building and operations. Impressed, I challenged Jordan to design a drone on a $2,000 budget. There was one catch: This drone had to be amphibious—able to land and take off from water and survey habitats both above and below water. In less than a month, Jordan had the drone designed, built and tested. Weighing in at just under five pounds, “Henri” (named for the early nineteenth century king of Northern Haiti) has a tough frame equipped with a high-def GoPro camera, GPS-enabled autopilot chip and other electronics tucked neatly inside an upside-down Tupperware container that serves as the perfect waterproof housing. Over a few days in May, our team collected several hours of videos using Henri along the coast of “Drones provide a new way to visualize our environment, giving greater insight for understanding and mapping our ever-changing world.” — Dr. Steve Schill 10 Caribbean Program 2014 Impact Report the newly declared Three Bays National Park (see Page 4) in northern Haiti. These videos are being used to document ecological conditions and validate habitat maps derived from satellite imagery. Henri gave us a different perspective on the coastal environment from what we normally see from satellite images or boat surveys. The video footage has given us us a sense of the ocean dynamics around the reef and allowed us to identify species of interest such as green turtles and rare corals. As our team packed up Henri and returned home, we had all gained a new appreciation for drone technology and what it offers the conservation world. Drones can provide enhanced information to protected area managers to allow them to better monitor impacts, assess the health of habitats and evaluate the success of management strategies. As for Jordan, he ended up getting an A in the class. Looking Ahead: The Opportunity in Cuba Off the southeastern coast of Cuba, in waters dubbed Jardines de la Reina or “Gardens of the Queen,” are some of the Caribbean’s most pristine and spectacular remaining reefs. The gradual opening up of Cuba has allowed scientists from The Nature Conservancy to discover for themselves the beauty and ecological importance of these and other outstanding Cuban reefs. Ironically, the same isolation that kept scientists out has also helped protect these habitats from many of the impacts of tourism, overfishing and pollution that have devastated many other Caribbean reefs. But Cuban reefs are just as vulnerable as those in neighboring countries to the impacts of climate change, including sea-level rise and coral bleaching, and as Cuba opens to researchers, it may also open to some of the destructive forces that come with economic development. Cuba is bigger than all the other islands in the Caribbean put together and is home to more than a third of all the reefs in the region. They are a haven for healthy populations of sea turtles, manatees, sharks and other large fish. Several Caribbean currents flow through Cuban waters, allowing it to function as a source of animals for other reefs in the region. Cuba’s 2,500 miles of coral reefs comprise nearly a third of all reefs in the Caribbean. Another feature that makes Cuba special is the government’s relatively early designation of marine protected areas—starting in the early 2000’s. But reserve managers in Cuba are challenged by a shortage of financial and technological resources to manage their parks efficiently. Cuban and U.S. laws currently limit the Conservancy’s role to advising, training and technical assistance. In partnership with the Cuban National Center for Protected Areas, Conservancy staff have been offering training workshops in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and other technical topics to help marine reserve managers and other government conservation staff build essential skills to better steward Cuban parks. With Conservancy staff serving as advisors to a variety of marine and terrestrial conservation projects throughout Cuba, we are poised to take on a greater role there as restrictions allow. As travel continues to flow more freely to Cuba’s shores, it is essential that the Conservancy and partners actively participate in safeguarding the relatively pristine environment that many of those visitors will flock to see. tHis page Left to Right Cuban Trogon (Priotelus temnurus), which is only found in Cuba © Allan J. Sander; Gardens of the Queen National Park, Cuba © Ian Shive opposite page Drone in action in Three Bays National Park, Haiti © Tim Calver; Inset Senior Scientist Dr. Steve Schill (center), with volunteers Jordan Mitchell (left) and Dr. George Raber (right) and “Henri”, the drone. © Tim Calver 11 The Nature Conservancy Caribbean Program 255 Alhambra Circle, Suite 520 Coral Gables, FL 33134 USA Nonprofit Org US Postage PAID Tucson, AZ Permit #2216 The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to conserve the lands and waters on which all life depends. Donate Now nature.org/caribbean Caribbean Board of Trustees Susan H. Smith, Chair Ramón D. Lloveras San Miguel, Co-Chair Robert A. O’Brien, Jamaica Advisory Council Chair Cathy Rustermier, Secretary Rosa Margarita Altagracia Bonetti Brea de Santana Joyce K. Coleman Jason Henzell Michael J. Kowalski Alicia Miñana de Lovelace Bruno Alexis Roberts Dr. Robert S. Steneck Jonnie Swann See why the Caribbean is worth defending. Join our campaign nature.org/defendparadise