Measuring Results - Pollinator Partnership

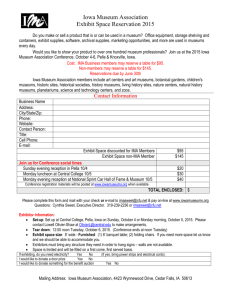

advertisement