CHRISTIAN-MUSLIM DIALOGUE IN THE LEBANESE CONTEX This

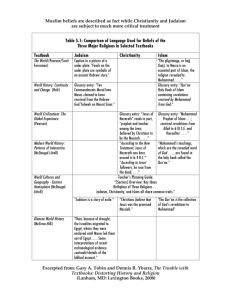

advertisement