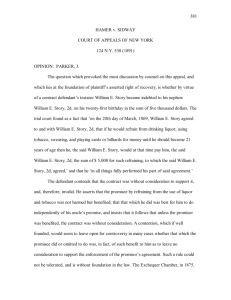

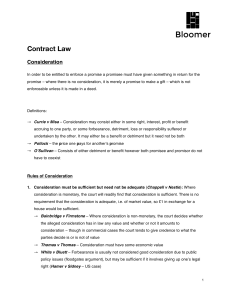

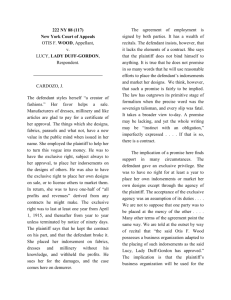

the doctrine of consideration - OPUS at UTS

advertisement