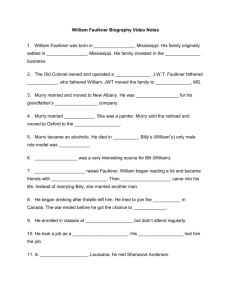

What Lies beneath Faulkner's “That Evening Sun”

advertisement