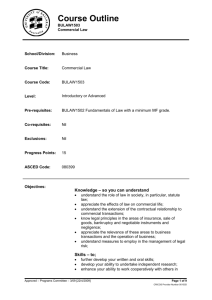

sketch notes - Monash Law Students' Society

advertisement

Monash Law Students’ Society STUDENT TUTORIAL PROGRAM 2014 SKETCH NOTES Constitutional Law Sponsored by: DISCLAIMER – PLEASE READ BEFORE CONSULTING THESE NOTES 1. The following SketchNotes have been prepared and provided by a law student as a skeleton or sketch of the course material for this unit; 2. It is the responsibility of users to make note of any changes to course content; 3. SketchNotes may exclude some topics, cases and legislation and may therefore be inconsistent with current Faculty of Law course content or recent developments in the law; 4. Neither the Law Students' Society nor its sponsors endorse or take responsibility for the quality or accuracy of these SketchNotes; 5. SketchNotes should not be solely relied upon; 6. SketchNotes are to provide users with a basis from which they can create individual and extensive notes for their own assessments; 7. SketchNotes are not to be replicated, either in part or in full, during Faculty of Law assessments for this unit; 8. SketchNotes are designed to be used as a teaching aid in the Student Tutorial Program; 9. For copyright reasons, SketchNotes are not to be printed or altered by users; 10. It is against the Monash Law Students' Society's policy to provide further materials to law students in relation to course content for this subject. Student may not make any such request to the Monash Law Students' Society or it its student tutors; 11. It is against the Monash Law Students’ Society’s policy for students to contact tutors directly via email. Any requests for further assistance outside of tutorials must be made to tutorials@monashlss.com. Questions regarding course content should be made to the relevant Faculty lecturers or tutors; 12. The aim of the Student Tutorial Program is to facilitate collaborative learning and increase student exposure to practice problems. It's role is not to substitute Faculty teaching or provide a way for students to pass assessments without engaging in course content; 13. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact Geerthana Narendren, Tutorials Officer at tutorials@monashlss.com INFORMATION FOR STUDENT USE NAME: Tim Rankin SUBJECT: Constitutional Law (LAW3201) STUDIED: Semester 1, 2013 LECTURER: Melissa Castan Topics included in the Semester 1, 2014 Reading Guide which are not referred to in these notes: Topic 2 – State Legislative Power Cases included in the Semester 1, 2014 Reading Guide which are not referred to in these notes: McCawley v R [1920] R v Barger (1908) Re Australian Education Union; ex parte Victoria (1995) R v Wakim; ex parte McNally (1999) Betfair v Western Australia (2008) Wotton v Queensland (2012) Monis v The Queen (2013) Unions NSW v New South Wales [2013] Commonwealth v Australian Capital Territory [2013] TOPIC 1 – Fundamental Concepts, Institutions and Instruments 1.1 Constitutional Law. Constitutional law is the main body of law which regulates the three arms of the Government: 1. The Executive – which administers and enforces the law; 2. The Legislature -­‐ which drafts the law; and 3. The Judiciary – which interprets the law. The Constitution provides an authority for the exercise of public power as well as any limits to that power. The Constitution also regulates the relationship between each arm of the Government. 1.2 Parliamentary Sovereignty. The principle of Constitutional Law which derives from the historic notion of the legislature of the prime law making body in a Westminster System (c.f. the sovereign in an absolute monarchy) The Commonwealth Government can only legislate on enumerated powers: s 51 Cth Const. State Governments can make laws with regard to any topic for their particular State (plenary power). However, note the impact of s 109 Cth Const. 1.3 Rule Of Law. Per Lord Bingham’s The Rule of Law (2010), the Law should: i. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. vii. apply equally to all; resolve disputes cheaply; be easy to understand; protect fundamental rights; be speedily enforced; respect international law; and prevent the abuse of power (by public officials) 1.4 Constitutional Convention. The political rules, customs or practices that are habitually followed by the Government, who is under a mere moral or political obligation to follow them. Breach of a convention does not attract any sanction. For example, the existence of a Prime Minister is a constitutional convention. 1.5 Representative Government. The doctrine of representative government refers to the concept that the lower house is composed of representatives chosen by the people: ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution. 1.6 Separation Of Powers. Pure Principle: The three arms of Government must be clearly separated to provide adequate cheques and balances to the system: On The Spirit of the Laws, 1748. In Australia we see a partial separation of powers between the Executive & Legislature and the Judiciary. Refer to State and Cth SOJP for Application. TOPIC 3 – Restrictive Procedures: Manner and Form 3.1 Restrictive Procedures. Under usual practices a bill will pass through both houses, with simple majority, then receive royal assent. Any additional restrictive procedure displaces the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty (that is, that each Parliament has power to make its own decisions and not be bound by previous Parliaments) and thus may only occur in limited circumstances. Manner and Form refers to a “condition and … requirement which existing legislation imposed upon the process of lawmaking”: A-­G (NSW) v Trethowan (1931) per Rich J. 3.2 Exam Structure. 3.2.1 Is the First Law Double Entrenched? • In order to be valid, a Manner and Form (‘MaF’) provision itself must be entrenched, or else the MaF provision can be repealed by the normal procedure: A-­G (NSW) v Trethowan. 3.2.2 Is the First Law restrictive procedure a permissible MaF provision? • • In line with the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty, earlier Parliaments should not impose MaF provisions which are so onerous as to amount to a curtailment of future Parliaments’ law making ability: West Lakes v SA (1980). MaF provisions cannot preclude any future changes to a law, If the law does so, this would constitute the Parliament abdicating its law-­‐making power and thus be invalid. 3.2.3 Is the Second Law (the one seeking to repeal the First Law) relating to the CPP of P? • • • In order for a MaF provision to be enforceable against subsequent laws, the laws trying to alter the MaF legislation must relate to the Constitution, Powers and Procedures of Parliament (‘CPP of P’): A-­G (NSW) v Trethowan. This is because the legal justification for the validity of MaF provisions is found in s 6 Australia Act and thus are limited to the wording of that section. The “Constitution” refers to the composition of the Parliament, including any features that give the Parliament its representative character: A-­G (WA) v Marquet (2003). TOPIC 4 – Characterisation As a starting point, the Commonwealth's (‘Cth’) legislative power is enumerated, rather than plenary. Thus a law will not be valid unless it is with respect to a Cth head of power (‘HoP’) under the Cth Constitution. Cf. State power which is plenary. 4.1 Characterisation. 4.1.1 Direct Characterisation -­ the characterisation of a law will be determined by the nature of the obligation, right or privilege the law regulates, changes or abolishes: Fairfax v FCT (1965) per Kitto J. 4.1.2 Dual Characterisation – dual / multiple characterisation of a law is permissible provided that one of the laws characters falls within a Cth HoP: Fairfax. • The constitution should be interpreted in accordance with the natural meaning of its text. Implied meanings are only to be construed where such meanings are necessarily or logically implied from the text of the Constitution itself: Engineers (1920) per Knox CJ, Isaacs, Rich & Starke JJ. 4.2 Incidental Power: s 51(xxxix). • • • If a law cannot be characterised as being ‘with regard to’ the heart of a HoP, it may still be constitutionally valid through the incidental scope of the Cth’s powers if it is ancillary or incidental to the express subject matter: s 51(xxxix). In Grannal Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Webb and Kitto JJ stated that every legislative power carries with it the authority to legislate with regard to acts, matters and things the control of which are found necessary to effectuate the laws main purpose. However, the existence of a power to legislate with respect to matters incidental to the exercise of power by the Federal Judicature does not, by itself, entail a power to legislate so as to have the federal judicature itself do those incidental things. An important distinction. Where the connection to the law’s main purpose is too remote, tenuous or exiguous it will fall outside the incidental score: Leask v Cth (1996) per Kirby J. 4.3 Purpose of the Law in Question. • • • Once a HoP over a subject matter is established it is irrelevant to inquire into the motives for the Cth’s exercise of that power: Huddart Parker (1931) per Dixon J. “It is no objection to the validity of a law otherwise within power that it touches or affects a topic on which the Commonwealth has no power to legislate”: Murphyores per Murphy J. The High Court is not to make a judgment as to the merits of the law and whether or not it is ‘good’ or ‘bad. Instead the question is whether or not the law is sufficiently proportionate to the aim within the power: Australian Communist Party. TOPIC 5 -­ Cth Head of Power -­ External Affairs Power – s 51(xxix) 5.1 Laws Implementing International Law/ Treaties. 5.1.1 Scope of the Treaty Document. • • The Cth Executive has an inherent prerogative power to ratify any international treaty/covenant: Teoh, regardless of the subject matter: Tasmanian Dams per Mason J. A signed treaty is not enforceable in Australian domestic law unless an Act of Parliament specifically enforces the treaty into law. The power is prerogative because it can be acted upon without the approval of the Parliament: Tampa. 5.1.2 Incidental Scope. • s 51(xxix) extends to matters which are reasonably incidental to those obligations under a treaty: Richardson. It can also be used to implement international instruments such as drafts, declarations and recommendations: ILO. 5.1.2 Limitations of Implementation. • • • • • Given the broad reaching power of the external affairs power, derived from the prerogative power to ratify treaties, there are four limitations on the implementation of treaties. Bona Fide – look to the language of the treaty / recommendation document. o Treaties must not be used as a means of conferring additional legislative power upon the Cth: Koowarta per Brennan J. o However, “the doctrine of ‘bona fides’ would at best be a frail shield available in rare cases”: Tas Dams per Gibbs CJ at [200]. Obligation – look to the language of the treaty / recommendation document. o The requirement for an ‘obligation’ was not explicitly confirmed by the HCA majority in Tas Dams nor was it explicitly rejected by the majority in ILO. Specificity– look to the language of the treaty / recommendation document. o Treaty must clarify what signatories must do in order to meet its standards: ILO. Conformity – look to the language of the implementing law. o the law must be reasonably capable of being considered appropriate and adapted to implementing the treaty”: ILO. 5.2 Law Dealing With Matters Of “International Concern”. • Laws relating to matters international concern may enliven s 51(xxix): XYZ. Look to the degree of the concern. 5.3 Extraterritorial Laws. • • A law will enliven the External affairs power (s 51(xx)) if it relates to a matter beyond the Cth’s geographical territories: s 3 Westminster Act. No requirement for a ‘nexus’ between the Cth and the law. The mere fact that the matter is external to Australia is sufficient: Polyukhovich and ILO Cf. XYZ per Callinan and Heydon JJ. 5.4 Laws Dealing With The Relations Of The Commonwealth With Other Countries/ Int Orgs. • Laws may enliven s 51(xxix) if they relate to the relations between Australia and other countries: Sharkey. May include ‘international persons’: Koowarta per Brennan J. TOPIC 6 -­ Cth Head of Power – Corporations Power – s 51(xx) 6.1 Is The Corporation A Constitutional Corporation (‘CC’)? s 51(xx) only extends to include those corporations which are foreign, trading or financial corporations (‘constitutional corporations’). 5.1.1 Foreign Corporations. • Any entity formed under the law of a foreign country and given a corporate legal personality either by the foreign law, or by Australian Law. Need not be a ‘trading’ or ‘financial’ foreign corporation to be regulated under this head of power: Incorporation case. 5.1.2 Trading and Financial Corporations. • A corporation is a trading or financial corporation if a substantial or sufficiently significant proportion of its activities comprise ‘trading/financial’ activities: Adamson (authority for this proposition re trading corporations); State Superannuation Board (authority re financial). 5.1.3 Inactive or newly established companies. • • A shelf company may be a trading or financial corporation, absent any current activities, on the basis that trading activities were specified as objectives in the shelf companies’ documentation: Fencott v Muller. Any legislation that purports to encapsulate all corporations, as opposed to just constitutional corporations will be rendered ultra vires: Concrete Pipes. 6.2 Scope of the Corporations Power. 6.2.1 Core Scope. • • If the law directs itself to a constitutional corporation then, applying the object of command test, the law is valid under the core scope of s 51(xx): Workchoices applying Re Pacific Coal. May also extend to cover natural persons working within a CC: Fencott and Actors Equity. 6.2.2 Incidental Scope. • • Laws will also enliven s 51(xx) where they are operating on persons who are acting in the course of their business relationship with a constitutional corporation: Workchoices. Per Gaudron J’s quote in Pacific Coal, applied by the majority in Workchoices, the incidental scope of the power extends to: o Cth regulation of the conduct of those through whom it acts, its employees and shareholders; and, o Cth regulation of those whose conduct is or is capable of affecting its activities, functions, relationships or business. 6.2.3 Incorporation of Companies. • • A Cth law will not be valid under s 51(xx) if it is directed at the incorporation of companies: Incorporation case. This is due to the tense of “formed” in s 51(xx). However, note this case seems almost conclusively overruled by Workchoices per Callinan J in dissent. C.f. Majority in Workchoices who explicitly said they were NOT disturbing the ruling in the Incorporation case. TOPIC 7 – Cth Head of Power -­ Financial Powers 7.1 Grants Power: s 96. 7.1.1 Does s 96 Provide the Source of the Cth Power? • Exam tip, s 96 is only relevant where a Cth Act purports to grant financial assistance to a state. The relevant law will likely be called “…. Grants Act” in any exam problem. 7.1.2 Does the law fall within the scope of s 96? • • • The Cth may attach any conditions whatsoever to a grant, so long as it does not legally compel the States to accept: Federal Roads Case; Uniform Tax Case #2 per Latham CJ. Contrary to s 51 powers, s 96 does not include the caveat of “subject to this constitution”. Therefore, there is no constitutional impediment to a s 96 grant that discriminates between states, including s 99: Moran per Latham CJ, confirmed in Uniform Tax Case #1. A grant could also legitimately be bestowed upon a State even if the State was obliged to pass on all of the money to another organisation/individual: DCT v Moran. 7.1.3 Limitations. • Cth cannot rely on s 96 with complete disregard of the prohibitions contained in s 51. Doing so would amount to using s 96 as a ‘colourable device’: Moran (Privy Council case). 7.2 Power to Appropriate and Spend. Per s 81 of the Cth Constitution the Cth has two powers; to appropriate, that is to earmark and separate money from the s 81 Consolidated Revenue Fund (‘CFU’), and to spend. It is unlikely that appropriations are justiciable: Pape per Hayne and Kiefel JJ. 7.2.1 Power to Spend. • However, neither s 81 nor s 83 expressly authorize the Cth to spend the appropriated money. There is a requirement that spend has been made ‘with regard to’ a valid Cth Head of Power (‘HoP’): Pape per French CJ. 7.2.2 Implied Nationhood Power. • The power to spend may be an element or incident of the executive power of the Cth, derived from s 61, subject to the appropriation requirement and supportable by legislation made under s 51(xxxix): Pape per French CJ at [111]. • This is the implied nationhood power (INP) and may be implemented in law as an incidental power pursuant to s 51(xxxix). Per French CJ in Williams the INP extends to: 1. powers necessary or incidental to the execution and maintenance of a law of the Commonwealth; 2. powers conferred by statute; 3. powers defined by reference to such of the prerogatives of the Crown as are properly attributable to the Commonwealth; 4. powers defined by the capacities of the Commonwealth common to legal persons; and 5. inherent authority derived from the character and status of the Commonwealth as the national government. TOPIC 8 – Limit to Legislative Power -­ Intergovernmental Immunities 8.1 State Immunity from Commonwealth Laws. 8.1.1 Introduction. • The implied doctrine of Intergovernmental Immunity (‘IGI’) exists to protect both levels of Government (Cth and State) and to maintain their autonomy and integrity. States will be immune from a Cth law if they can demonstrate that the law impairs the capacity of the State(s) to function as a government: Austin affirmed in Clarke. 8.1.2 Starting proposition. • The Cth has the general power to regulate or bind State Governments, agents and instrumentalities: Engineers. 8.1.3 Express Limitations. • • The Cth cannot bind States in areas where it has no head of power. Nor can it exercise such power in breach one of the express or implied prohibitions on Cth power, e.g. s 116 or the IFPC. 8.1.4 Implied Limitations. • The Cth can not impair a State’s capacity to function as an independent Government: Melbourne Corporation, reformulated in Austin, affirmed in Clarke. a. Impairment • The Cth cannot pass a law which prevents a state from being able to exist or function as a State: Melbourne Corporation. Per French CJ in Clarke there are six non-­‐decisive factors for determining impairment: 1. Cth singled out a State and imposed a special burden not imposed on general persons? 2. Cth law of general application imposes a particular burden on the States? 3. Cth law effecting States capacity to exercise constitutional powers? 4. Cth law effect States exercise of functions? 5. Nature of capacity or functions affected? 6. Subject matter of the law? b. Discrimination • • • • Is not a decisive factor but rather “may be an indication of an attempted impairment of (a State Gov’t) functionality”: Austin per Kirby J. Direct discrimination arises when one (here a State govt entity) is treated differently than other persons (or entities). Direct discrimination is discrimination in “application” or “form”: QEC. Indirect discrimination arises when a rule or law is applied neutrally, but impacts disproportionately and detrimentally on a certain group (or State govt). It is discrimination in substance or effect, rather than form: QEC. However, a discriminatory law may nonetheless be valid if it achieves a ‘rational’, ‘non-­‐discriminatory’ purpose: Richardson per Brennan J. 8.2 Commonwealth Immunity from State Laws. 8.1.1 Definition. • • Despite obiter in Engineers affirmed in Pirie, State Parliaments can not seek to alter or impair the capacities and functions of the Cth Govt: Cigamatic. The States can bind the Cth in the exercise of those capacities: Henderson per majority. 8.1.2 Analysis. • • Pursuant to s 16 of the Victorian Constitution Act 1975 the Vic Parliament has plenary power. However, where a state law seeks to regulate the Cth’s capacities, it will be in breach of the implied intergovernmental immunity as articulated in Henderson. a. Exercising Capacities • • Where the Cth treats itself as a private citizen (e.g. entering into contracts) then this shall be an exercise of capacities: Uther per Dixon J. Entering into landlord tenant relationships pursuant to the Defence Housing Authority Act 1987 (Cth) in Henderson. b. Affecting Capacities • An example of this would be a law affecting the prerogative or executive rights of the Cth. That is, their inherent rights where the Executive does not need to seek the approval of the Parliament. 8.1.3 Exceptions. a. Civil • • Where the Cth is engaged in a civil suit, s 64 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) shall apply and the Cth’s substantive rights must be governed by the same laws which would govern a private litigant in the same situation: Maguire affirmed in Evans Deakin. The rule of law must be applied equally. Note: Henderson involved a tribunal, not a suit, and thus s 64 was not considered. b. Criminal • The Cth cannot authorise its agents to perform their functions in contravention of the criminal laws of a State, and cannot confer immunity upon them: Pirie, affirmed in Henderson per Brennan CJ. TOPIC 9 -­ Separation of Powers 9.1 Commonwealth Separation of Judicial Power. 9.1.1 Two key principles. • The Cth doctrine of the Separation of Judicial Power (‘SOP’) is implied from the text of the Const (ss 1, 61, 72) as well as the structure of the constitution: Vic Stevedoring. There are two key principles which define the Cth SOP. • • Firstly, only Chapter Three Courts of the Const’n (‘Ch III Courts’) may exercise judicial power (‘Principle 1’): Wheat case. Secondly, Ch III Courts may only exercise judicial power (‘Principle 2’): Boilermakers. 9.1.2 Is the power in question a “Judicial Power”? • Judicial Power (‘JP’) is not clearly defined in either the legislature or case law: Huddart Parker per Griffith CJ. Instead we must consider a number of factors: o Enforceability – a binding or conclusive decision points towards the power in question being Judicial Power: Brandy. o Breadth and Nature of Discretion -­‐ The wider the discretion conferred on decision-­‐maker, less likely the function is judicial power: R v Spicer. o Existing Rights and Duties -­‐ Creating new rights is consider NJP (e.g. making Industrial awards in Waterside). o Dispute or controversy -­‐ Not a decisive factor, however, if a decision maker acts impartially in settling a controversy between two parties, points to JP (excluding ex-­‐parte hearings: Davison. o Power to interpret law – the power to interpret a law is not, of itself, indicative of JP. The power must be linked to a decision regarding a matter: Momcilovic. o Historical Consideration – control orders regarding prospective risks were traditionally issued by judges, indicating they were JP: Thomas v Mowbray. 9.1.3 Who is exercising the power? Those entities considered as Ch III courts is set out in s 71. 1. The High Court of Australia. 2. Federal Courts Created by Parliament: i. Federal Court; ii. Family Court; iii. Federal Magistrates Court; iv. Industrial Relations Court; and v. Any new created Ch III Courts must have tenure until 70 years age – s 72 Const; Waterside Workers. The purpose and intention of a bodies’ creation will be important however the name of the body is not conclusive: Waterside Workers. 3. Courts vested with Federal Jurisdiction. i. Courts in the State Hierarchy – State Supreme and State Magistrates’. 4. A single Federal Judge: Hilton v Wells. Vesting a Fed Court judge with Ch III power is the same as vesting a Ch III Court with that power. 9.1.4 Exceptions to Principle One -­ only Ch III Courts May Exercise JP: Wheat Case. a. Delegation • • Judicial power may be delegated to non-­‐judicial bodies by Ch III Courts: Harris v Caladine or Court Registrar’s case. Per Mason CJ and Deane J in Harris v Caladine there are two limitations: o Judge must continue to bear major responsibility for the exercise of the JP; and o Decision must be subject to review or appeal by a judge of the court on questions of both fact and law. b. Discrete Situations • • • Military tribunals may exercise federal JP: R v Bevan. If the Court sits outside the chain of command it will not be supported by s 51(vi): Lane v Morrison. Public service disciplinary tribunals may exercise federal JP: R v White. Parliament may punish for contempt pursuant to s 49 of the Cth Const: R v Richards. 9.1.5 Exceptions to Principle Two. a. Incidental Power • • A law may convey NJP to a CH III Court if that power is incidental to its effective exercise. Even if a questioned function (“F1”) is linked to a judicial function (“F2”) as part of one statutory scheme, F1 is neither an incident nor an element of the judicial function F2: Wainohu per French CJ and Kiefel J. o In Wainohu F1 was a declaration of a club (Hells Angels), F2 was a control order. b. Persona Designata • A Judge may validly exercise NJP while acting in their personal capacity as opposed to their official capacity: Hilton v Wells. This exception is limited by the two-­‐stage test in Grollo per Brennan CJ, Deane, Dawson and Toohey JJ, that is, that the Judge must consent to the conferral of NJP and that the NJP must not be incompatible with the judge’s judicial duties. • However, the Grollo test for incompatibility was later revisited in Wilson where the majority outlined a three stage test for determining when a NJP is incompatible to judicial function: 1. Is the NJP an integral part, or closely connected with the functions of the legislature or executive? If yes; 2. Does the function required to be performance independently of any non-­‐ judicial institution, advice or wish from legislature or executive? If yes; 3. Does this function require a judicial matter of performance. E.g. does it require the following of rules of evidence, hearing two parties, etc. 9.1.6 Conclude. • • • State whether the law is in breach of either principle. State why an exception does or does not apply. If no exceptions apply, the law shall be unconstitutional for breach of the Boilermakers principles of Cth SoJP. 9.2 State Separation of Judicial Power. 9.2.1 Starting Point – Kable. • • Unlike the Commonwealth, State Parliaments have plenary power (Union Steamship) and inherently flexible state constitutions (Taylor). Thus, there is no State Doctrine of the Separation of Judicial Powers (‘SoJP’). However, since Kable, it is clear that Ch III of the Cth Constitution invalidates State legislation insofar as it confers jurisdiction on State courts that compromises the institutional integrity of State Courts and affects their capacity to exercise Federal Jurisdiction vested by Ch III: Fardon per McHugh J. 9.2.2 Is body capable of being vested with federal jurisdiction? • The following Courts are capable of being vested with federal jurisdiction: o Supreme Court – Kable; o Magistrates’ Court-­‐ Totani; and o Other State Courts– K-­Generation. 9.2.3 Has a State vested non-­judicial power upon the body? If so, does this power undermine the institutional integrity of the Court? • If a NJP undermines the institutional integrity of a court, capable of being vested with federal judicial power, then Ch III will prevent the State from vesting the NJP: Kable. • There are a number of relevant factors: o Appearance of independence and impartiality: Wainohu per French CJ & Kiefel J. o Is the act Ad hominem, that is, does it target one person or group as opposed to a class of persons: Kable, Fardon, Baker. o Does the court have discretion over conduct or outcomes: IFT, Totani. o The standard/onus of proof: Fardon. o Requirement on court to give reasons: Wainohu per Deane J. o Has the public confidence been undermined: Kable. 9.2.4 Does an exception apply? a. Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities • • Judges must interpret legislation, as far as possible, consistently with the Charter. If they are unable to, Judge’s may choose to issue a declaration per s 36 of the Charter. According to majority in Momcilovic making a declaration under s 36 of Vic Charter is a NJP but does not offend the Kable principle. B. State SoJP – Persona Designata? • • • It was noted by the majority in Wainohu that both Wilson and Kable have a common footing in constitutional principles. Wainohu, at [105] that constitutional principle has as its touchstone protection against legislative or executive intrusion upon the institutional integrity of the courts, whether federal or State.... It follows that repugnancy to or incompatibility with that institutional integrity may be manifested by State (and Territory), as well as federal, legislation. It is arguable that we could apply the same incompatibility test from Wilson, however, were this the case, the principles guiding this section would originate in Kable, not Boilermakers. TOPIC 10 -­ Freedom of Interstate Trade and Commerce – s 92 10.1 Starting Point. • • • Per s 92 trade, commerce and intercourse among the states must be absolutely free. Trade and Commerce – Apply an ordinary meaning to the words, parts of that class of relations that the whole world calls trade and commerce. ‘[T]he mutual communings, negotiations, bargain, transport and the delivery’: McArthur. Intercourse -­ Moving of goods between the states, includes forms of communication. 10.2 The Four-­Stage Test from Cole v Whitfield. 10.2.1 Is there a burden on Interstate Trade and Commerce? • For example: a tax, fee, ban or prohibition. 10.2.2 Is the Burden Discriminatory? • • A law will discriminate against interstate T + C if the law on its face subjects that T + C to a disadvantage or if the practical operation of the law produces the same result: Cole. s 92 does not immunise traders from governmental controls: rather, s 92 demands an ‘equality of treatment’ between interstate and intrastate trade: Cole. The fact that an individual trader is discriminated against is irrelevant as s 92 protects trade, not traders: Barley. 10.2.3 Does The Burden Have A Protectionist Effect? • • To be prohibited a law must, either in its purpose or practical operation, provides a protectionist measure as between States: Betfair #2, Sportsbet. You can either have: o import restrictions (Bath) where there is an undermining of the advantage of interstate sellers; or o export restrictions (obiter in Barley) if the State is trying to prohibit the export of scarce resources this may be discriminating in a protectionist sense. 10.2.4 Exception: Does The Law Achieve A Legitimate, Non-­Protectionist Purpose? • • • • Notwithstanding establishment of the first three elements of the Cole test, a law may nonetheless succeed if it can be established that its protectionist effect is incidental to a non-­‐protectionist purpose. The question is whether it is appropriate and adapted to the purpose: Castlemaine Tooheys. If the law could have achieved the same non-­‐protectionist effect by a non-­‐ discriminatory method then this will indicate not A+A. If the law is disproportionate to its aim, this will indicate not A+A. TOPIC 11 -­ Implied Rights, Political Communication and Voting 11.1 Implied Freedom of Political Communication (‘IFPC’). • • The Commonwealth Constitution expressly protects very few rights, and instead operates as a ‘grant of power’. However, the High Court has recognised that certain rights may be implied from the text of the constitution: Lange. In Lange the High Court unanimously found that an implied freedom of political communication (‘IFPC’) could be drawn from ss 7, 24, 64 and 128 of the Commonwealth Constitution. 11.1.1 Two-­Stage Test in Lange. • In order to determine if conduct falls within the scope of the IFPC, we must look to the two-­‐stage test proposed in Lange. a. Is there a burden? • • • Ask, does the law burden freedom of communication about Government or Political matters either in its terms, operation or effect? Political communication is the ability of people to communicate with one another with respect to “matters that could affect their choice in federal elections or constitutional referenda or that could throw light on the performance of Ministers”: Lange at [571]. Includes verbal & non verbal forms of communication: Levy v Vic – killing ducks. b. Is the Burden valid? • • Once the first stage is satisfied, we must determine whether or not the burden is a legitimate limitation on this implied freedom. Per McHugh J in Coleman we the law must be appropriate and adapted (‘A+A’) to serve a legitimate end in a manner which is compatible with the maintenance of the constitutionally prescribed system of representative and responsible (‘R + R’) government. o Is the law designed to achieve an end which is compatible with the maintenance of representative and responsible government? For example: Improving the quality of political debate and reducing the cost of electoral campaigns: ACTV. Protecting authority of industrial relations commission: Nationwide News. Quality control of migration advice: Cunliffe. Public Safety: Levy. Protect and facilitate the voting system: Lange. Protection of public order (prohibiting racist offensive conduct): Coleman. Protection of politician’s reputation: Theophanous; Lange. o Are the means adopted appropriate and adapted to achieving that end? 11.2 An Implied Right to Vote. 11.2.1 Source of the right. • In Roach Gleeson CJ of the High Court found that an implied right to vote (‘IRV’) could be implied from ss 7 and 24 of the Commonwealth Constitution. 11.2.2 Limitations on the Right. • • The IRV is not absolute and that it may be contravened for a substantial reason: Roach per Gleeson CJ. To determine this, you must show that the law is appropriate and adapted (‘A+A’) to a purpose consistent or compatible with the maintenance of representative Government: Roach per Gummow, Kirby and Crennan JJ. o In Roach the previous Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 prevented all prisoners, serving a sentence of three or more years, from voting. The 2006 Amendment being challenged prevented ALL serving prisoners from voting. The former was A+A, the latter was not. o In Rowe a law altered the writ procedure by which the electoral office processed enrolments. Effectively meaning 100,000 late applications could not be processed before that election. A slim 4:3 majority found the laws invalid. French CJ stated that the administrative benefit upon the Electoral Office was not proportionate to the impact on the late applicants. Not A+A. 11.2.3 Judicial Discussion. • • • Hayne and Heydon JJ (dissent) in Roach – there is no implied right to vote in the constitution. The Constitution does not set in place the franchise for adults and it is therefore permissible for the Cth Parliament to adjust the scope of the franchise. Kiefel J (dissent) in Rowe -­‐ the provisions served the legitimate objects of fraud prevention and of seeking to ensure greater compliance with electoral obligations. No denial of the franchise was involved. It was not possible, logically, for the plaintiffs to suggest that the impugned provisions were invalid, but those allowing for a few more days were valid. Gummow & Bell JJ in Rowe – preventing electoral fraud, with no evidence of previous systematic fraud, is not a substantial reason. TOPIC 12 -­ Inconsistency – s 109 12.1 Scope of the Principle. • • • Where a State Law is inconsistent with a Cth Law the State Law is rendered, to the extent of the inconsistency, invalid: s 109 Const’n. Administrative Orders and Directions made under Cth Laws are not laws for the purposes of s 109: Airlines of NSW v NSW (No 1). Awards made pursuant to a Cth Act will be ‘laws’ for the purposes of s 109: Ex Parte McLean. Exam Note: As a starting point establish that valid laws are in fact operative on the subject matter in question. If either the Cth or State law is found to be invalid or ultra vires (for reasons other than s 109) there will of course be no need to test for inconsistency. Then three distinct tests to determine inconsistency. 12.2 Simultaneous Obedience – a direct test. • • Where a person is bound to comply with both State Law and Cth Law, simultaneously, that State Law should be invalidated pursuant to s 109: McBain v Vic. In R v Licensing Court of Brisbane – a Qld Law required a referendum on the same day as Senate elections however the Cth Law prohibited referenda on days when Senate elections are held. It would be impossible to obey both laws. 12.3 Conferral of Rights – a direct test. • • • If a State Law alters, impairs or subtracts from rights conferred by a Cth law it will be invalidated per s 109: Clyde Engineering v Cowburn. For example, in Clyde Engineering a NSW Act set ordinary working hours at 44 h/p week. A Cth award fixed ordinary working hours at 48 hours per week. The NSW Act was invalid for diminishing rights conferred by the Cth Law. In Mabo #1 a QLD Act purported to extinguish any traditional rights to land. The Cth Racial Discrimination Act 1975 required all persons to enjoy rights to the same extent. The Qld Act was invalidated on a conferral of rights argument as it distinguished property rights on race. 12.4 Cover the Field – an indirect test. • A State Law may be invalidated pursuant to s 109 if Cth has expressly or impliedly evinced its intention to cover the whole field: Clyde Engineering v Cowburn per Isaacs J. 12.4.1 Identifying the Field • You must identify the “field” of both laws. Ask, what is the area / topic / subject matter of each legislative scheme. • For example, in O’Sullivan v Noarlunga both laws were characterising as regarding “slaughtering stock for export”. 12.4.2 Does the State Law encroach? • The broader the characterisation of law the more likely you will establish encroachment. 12.4.3 Cth Intention to ‘Cover the Field’ • • Assuming the first two elements are satisfied, there will still be no inconsistency unless it can be demonstrated that Cth intends to set out the exhaustive expression on the matter: Ansett v Wardley. This intention may be demonstrated by express words or implicitly. a. Express Intention • • Demonstrated through express words that Cth either intends to oust the operation of any State Law or to complement State Law. E.g. Momcilovic -­‐ Victorian Criminal Code s 300.4 is “not intended to exclude or limit the concurrent operation” of any State or Territory laws. b. Implied Intention – Courts may look to two non-­‐decisive indicia of intention to cover the field. • • The detail of the legislative regime (e.g. see O’Sullivan); and/or The subject matter of the legislation (e.g. see Viskauskas v Niland 1983). 12.5 Inconsistent Criminal Penalties • • • Conflicting Cth & State criminal penalties often lead to inconsistency “at least when the penalties are diverse” per Dixon J in McLean (1930) Where State and Cth laws impose diverse penalties for the same conduct this contravenes s 109: McLean per Dixon J. Different penalties for the same conduct may amount to direct inconsistency, because of the modification of rights of the person: R v Lowenthal: Ex parte Blacklock per Mason J. Also note, s 30 Acts Interp’n Act 1901 (Cth) which prohibits double jeopardy between Cth and State legislation.