Environmental auditing: the case of Ecuadorian industry

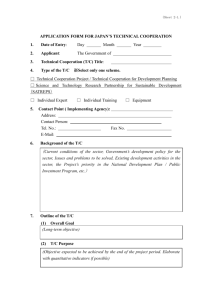

advertisement