Criminal Profiling: Techniques, Origins, and Validity

advertisement

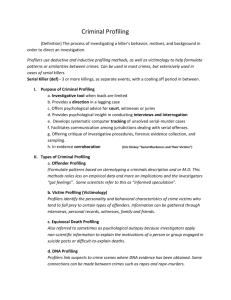

2 1 A European Association of Psychology and Law - Student Society Publication August 2011 FACT SHEET: Criminal Profiling Michael Wafler, B.A. honours student & Julia Shaw, PhD Candidate What is criminal profiling? Criminal profiling, also known as offender profiling, is best understood as a series of investigative techniques used to determine the characteristics of an unknown criminal offender. Profiling relies on the basic premise that an individual’s personality and mannerisms guide their everyday behaviours, including their criminal actions. Evaluating evidence found at the scene of a crime, a profiler relates this information to known behaviours and personality attributes derived from past crimes of other criminals who demonstrated similar traits. Utilizing these similarities, a profiler constructs a description, or profile, of what police investigators should characteristically look for in a suspect. Despite sounding valid in principle, these practices, the technique development, and the ways in which profiling has been used to locate suspects, are surrounded by controversy. Origins While there has been a recent bloom of interest within popular culture, criminal profiling actually has a long history. One of the first criminal profiles was generated in 1956 by James Brussels. Brussels constructed the first modern profile in response to a series of bombings attributed to an individual known then as the “Unabomber”. Using his background in psychiatry, Brussel made deductive predictions about the offender based on his behaviours. In this profile, Brussel provided surprisingly specific descriptions regarding the characteristics of the unknown offender. When finally apprehended by the New York police, it was found that the “Unabomber” matched Brussels’ description with a great deal of accuracy. Through this apparent success, Brussels’ profile was heralded as a triumph, spurring interest by the Federal Bureau of Investigations. Intent on using and developing these techniques, the FBI formalized many of the methods used in Method profiling today. Pioneered by FBI Special Agent John Douglas, modern traditional offender profiling consists of six main steps; input, decision process, crime assessment, criminal profile formation, investigation, and apprehension. Input refers to the acquisition and organization of crime scene evidence. Once the available evidence has been established, decision processing categorizes evidence into patterns, which are analyzed for predictive characteristics. Crime assessment involves reconstruction of the crime to uncover offender motivation in committing the crime. Once the required data has been established, the profiler consolidates the information and forms a criminal profile. This profile is forwarded to crime investigators and used as an aid to further the investigation. Finally, in the apprehension phase, the profiler continually checks for profile accuracy against newly uncovered evidence, especially if the offender is apprehended and admits guilt. Profilers also evaluate several other crime components, specifically with regard to serial crime. One crime feature commonly associated with profiling is the Modus Operandi (M.O), specific techniques utilized by a criminal across their crimes. For more information visit: www.eaplstudent.com Contact us at: eaplstudent@gmail.com 1/5 1/4 4 3 A European Association of Psychology and Law - Student Society Publication October 2011 FACT SHEET: Criminal Profiling Conversely, the M.O. can adapt and change over time making it difficult to utilize in a profiling. Many perpetrators of serial crime engage in ritualistic behaviours, and these repeat behaviours can contribute to the cross-crime linkage by profilers and to identification of the offender themselves. Staging, the act of manipulating a crime scene to hamper or re-direct investigation, escalation of crime severity, and the time and locations of the crimes also play key roles in profile formation. Art or science? Unlike most professionally utilized psychological measures and techniques, methods of criminal profiling developed by the FBI appear to have followed guidelines lacking in proper methodology, and research standards. Upon formation of the FBI behavioural science unit, interviews were conducted with a selection of American serial killers aimed toward gathering information to be used in analysis of future crimes. Concerns have been raised about the ways in which this data was collected. A significant concern has also been raised regarding the subjective nature of profile construction, which often relies heavily on personal experience and “common sense”, rather than scientifically backed methods. There is also concern about the tremendous number of false alarms generated by profilers. In other words, more often than not, profilers are incorrect in the details they generate about offenders thereby pointing criminal investigators towards innocent suspects. Finally, evidence strongly suggests that trained profilers do not perform better at predicting the characteristics of unknown perpetrators than the general public. Criminal profiling should be considered a pseudoscientific technique until empirical studies can support the notion that profilers can actually predict the characteristics of offenders above the level of chance. Conclusion To date there is a lack of scientific evidence in support of the techniques used in criminal profiling, and the proclaimed successes of criminal profilers. The unscientific basis of profiling calls into question the validity of the methods it has spawned, and the ways in which these methods are used today. Academic evaluation and criticism promotes the need for further research and scientific research on whether or not profiling can be a useful tool in criminal investigations. Quick summary: • • • • Profilers try to determine characteristics of an unknown offender, especially in suspected serial crimes The Unabomber was one of the first successfully profiled offenders Formalized by the FBI, profiling and consists of 6 stages Profiling is considered an art and is not backed by scientific research. Academics often refer to it as a “pseudoscience”. 2 For more information visit: www.eaplstudent.com Contact us at: eaplstudent@gmail.com 2/4 1 2 A European Association of Psychology and Law - Student Society Publication August 2011 FACT SHEET: Criminal Profiling Where can I get more information? Information from the EAPL-S is available online, in PDF, or as paper brochures sent through the mail. If you would like to have EAPL-S publications, you can order hardcopies for a nominal fee through eaplstudent@gmail.com. References 1. Alison, L., Bennell, C., Mokros, A., & Ormerod, D. (2002). The personality paradox in offender profiling: A theoretical review of the processes involved in deriving background characteristics from crime scene actions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 8(1), 115-135. doi:10.1037/10768971.8.1.115 2. Alison, L., Smith, M. D., & Morgan, K. (2003). Interpreting the accuracy of offender profilers. Psychology, Crime & Law, 9, 185-195. doi:10.1080/1068316031000116274 3. Devery, C. (2010). Criminal profiling and criminal investigation. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 26, 393-409. doi:10.1177/1043986210377108 4. Douglas, J. E., Burgess, A. W., Burgess, A. G., & Ressler, R. K. (1992). Crime classification manual. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?id=Il2lksVFS9oC &lpg=PT9&ots=DFwBWBgIr1&dq=Crime%20cl assification%20manual&lr&pg=PT11#v=onepag e&q&f=false 5. Douglas, J. E., Ressler, R. K., Burgess, A. W., & Hartman, C. R. (1986). Criminal profiling from crime scene analysis. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 4, 401-421. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370040405 6. Gregory, N. (2005). Offender profiling: A review of the literature. The British Journal of Forensic Practice, 7, 29-34. 7. Muller, D. A. (2006). Criminal Profiling: Real Science or Just Wishful Thinking?. In C. R. Bartol, A. M. Bartol, C. R. Bartol, A. M. Bartol (Eds.) , Current perspectives in forensic psychology and criminal justice (pp. 55-66). Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc. 8. Pinizzotto, A. J., & Finkel, N. J. (1990). Criminal personality profiling: An outcome and process study. Law and Human Behavior, 14, 215-233. doi:10.1007/BF01352750 9. Schlesinger, L. B. (2009). Psychological profiling: Investigative implications from crime scene analysis. Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 37, 73-84. 10. Snook, B., Eastwood, J., Gendreau, P., Goggin, C., & Cullen, R. M. (2007). Taking stock of criminal profiling: A narrative review and meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(4), 437-453. doi:10.1177/0093854806296925 11. Torres, A. N., Boccaccini, M. T., & Miller, H. A. (2006). Perceptions of the validity and utility of criminal profiling among forensic psychologists and psychiatrists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37, 51-58. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.37.1.51 For more information visit: www.eaplstudent.com Contact us at: eaplstudent@gmail.com 3/5 3/4 A European Association of Psychology and Law - Student Society Publication October 2011 FACT SHEET SERIES INFORMATION EAPL-S publications are in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without the permission from the European Association of Psychology and Law Student Society (EAPL-S). EAPL-S encourages you to reproduce them and use them in your efforts to improve awareness of issues in psychology, corrections and law. Citation of the European Association of Psychology and Law as a source is appreciated. However, using these materials inappropriately can raise legal or ethical concerns, so we ask you to use these guidelines: • EAPL-S does not endorse or recommend any commercial products, processes, or services, and publications may not be used for advertising or endorsement purposes. • EAPL-S does not provide specific medical advice or treatment recommendations, legal action or referrals; these materials may not be used in a manner that has the appearance of such information. • EAPL-S requests that organizations not alter publications in a way that will jeopardize the integrity and "brand" when using publications. • Addition of logos and website links may not have the appearance of EAPL-S endorsement of any specific commercial products or services or medical treatments or legal services. If you have questions regarding these guidelines and use of EAPL-S publications, please contact the EAPL-S at eaplstudent@gmail.com 4 For more information visit: www.eaplstudent.com Contact us at: eaplstudent@gmail.com 4/4