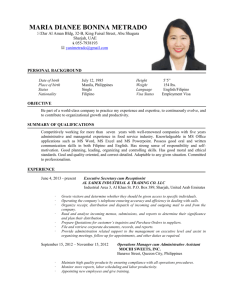

Chapter 1 – Profile

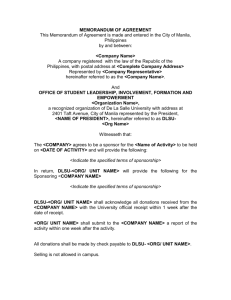

advertisement