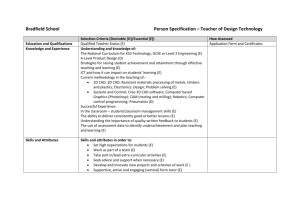

The Situation – Context Case Study Summary

advertisement

FROM EMERGENCY TO LONG TERM PROGRAMMING INTERVENTIONS: CHF’S APPROACH TO BUILDING RESILIENCY Canadian Hunger Foundation (CHF) The Situation – Context Through the sustainable livelihoods approach, CHF works with smallholder farmers around the world to improve their resiliency in the face of challenges brought on by the effects of climate change. Although most of CHF’s programming is longer term, we have also worked in countries following natural disasters, such as droughts, floods, tsunamis and earthquakes. CHF will compare two case studies -- one programming intervention from a slow onset setting (2003 drought in Ethiopia) and one from a rapid onset setting (2005 earthquake in Pakistan). Case Study Summary CHF Intervention: Partnership for Food Security Project (2003 – 2010, CAD $11.6 million) In response to the Government of Ethiopia’s appeal following the drought in early 2003, CHF adopted a sustainable livelihoods approach to promote a shift away from dependence on food aid. Implemented in partnership with the Organization for Rehabilitation and Development in Amhara (ORDA), our local partner in Ethiopia, in three phases as follows: - Phase I (March 2003 to July 2004) (CAD $3.075 million): During the Emergency Response Phase, provided early relief and asset protection for hard-hit families in the Batiworeda and supported rehabilitation activities through an employment generating scheme. - Phase II (August 2004 to September 2005) (CAD $1.3 million): The Bridging Phase provided the groundwork for the final phase. - Phase III (October 2005 to September 2010) (CAD $6.7 million): Relief-to-development programming, shift away from dependency on food aid to sustainable livelihoods. The Change: Key Results/Successes High number of PFS II beneficiaries graduated out of the safety net program – despite being the most vulnerable in the woreda. Cash incomes tripled – from increases in annual crop sales, livestock sales, fruit and vegetable sales. Women benefited more than men from sheep, goat and egg sales. The % of households with at least some irrigated land rose by 50%. Access to agricultural and veterinary extension services more than tripled, improved conservation agriculture practices adopted. Improved sanitation and hygiene, increased access to potable water, reduction in time spent collecting water, increase in the use of family planning services, improved maternal and child care. Higher enrollment and literacy rates, increased access to schools. Improvement in the status of women. Roads constructed and rehabilitated (in the pre-safety net period). Land cover improved, protected enclosed areas, tree planting, strict regulation of production of charcoal. Project interventions were designed integrating Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) and Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) CHF Intervention: Supporting Early Recovery and Building Long-term, Sustainable Livelihoods (2006 – 2012, CAD $10.2 million) Following the October 2005 earthquake in Pakistan, to meet both the immediate needs as well as more long term community rehabilitation and sustainable livelihood development. Implemented in partnership with HAASHAR Association and the Sungi Development Foundation, our local partners in Pakistan, in three phases as follows: - Phase I (May 2006 to October 2006) (CAD $200,000): Providing livelihood assets to approximately 400 most vulnerable earthquake affected households for agriculture and livestock, and training 35 livestock extension workers. - Phase II (January 2007 to December 2008) (CAD $5.0 million): Providing livelihood assets to 11,000 ultra-poor households mainly for agriculture, livestock and income generation. - Phase III (January 2008 to October 2012) (CAD $5.0 million): Enhancing communitybased NRM, Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation, improving community physical infrastructure (roads, drinking water supply) and building disaster management capacity among vulnerable villages in same 11,000 ultra-poor households. The infrastructure component also involved non-ultra-poor households from same villages which provided indirect effects particularly through community physical infrastructure (CPI) to a further 16,000 non-ultra poor households. The Change: Key Results/Successes Improved roads and paths mean households have better access to markets, health, education and other facilities. Increases in assets (kitchen gardening, toolkits, sewing machines, orchards) and in productivity (through provision of water, seeds, fertilizer, plants, training). Decrease in water borne diseases (diarrhea) in children by 38-54%. Training provided in basic agriculture, sewing, health and hygiene, advanced agriculture, livestock, orchards, first aid, and logistics. Improved knowledge, better livestock management, more food for home consumption, increased awareness, savings and some income increases. Women have benefited through increased confidence and general awareness levels, increased mobility, collective capacities and reductions in time cost and physical labour. Improved knowledge and skills of project beneficiaries so they can address CCA and DRR in their day-to-day living. Village level Disaster preparedness and contingency planning in place. Appropriate institutional (government and NGO) linkages were establishedto ensure adequate support during crisis and recovery stage. Carry out local level Risk and Vulnerability Identification, and Risk Communication. CHF strategy to effectively coordinate food assistance and long term approaches to food security (and livelihoods) in these countries. Emergency Response Food Assistance and Restoration of Livelihoods Humanitarian Phase Early Recovery Development Phase Recovery and Reconstruction Increased Agriculture and Livestock Production Climate Change Adaptation Income Diversification Capacity Development ProductionClimate Change Adaptation Climate Change Adaptation Food Security and Resiliency Disaster Risk Reduction Environmental Sustainability Disaster Risk Reduction Approaches that can effectively coordinate food assistance and long term food security and livelihoods include: 1. Local level risk, vulnerability and capacity identification and communicationarecrucial to ensure appropriate transition from humanitarian assistance to long-term food security and sustainable livelihoods. Building resiliency of vulnerable and food insecurepopulations should focus equally on agriculture and livelihood interventions. 2. Ensure adequate time for pre-project assessments, incubating and scaling up: Projects requiring deep and intensive focus at individual and household levels, data collection, validation and the kind of nurturing and mentoring that is required for capacity development and gender mainstreaming, need to be implemented in a “phased” approach and over longer timeframes. 3. Intensify coverage and community mobilization: More intensive and inclusive approach to community mobilization which expands the membership base allows project planners to orient communities on the rationale, objectives and need for strong community organizations which include the ultra-poor. This requires working with broader communities and negotiating linkages for mature organizations. It requires not only resources but an effective community mobilization strategy for the project. 4. Alignment with local government’s policies and program: Involvement of local government in planning and implementation of programs, as well as capacity building exercises, for purposes of better buy-in and increased chances for sustainability. 5. Mainstream ultra-poor into local social structures: Community institution building inclusive of all members of the community requires time and a multi-pronged approach. 6. Foster buy-in for community physical infrastructure: Physical Infrastructure Committees (PICs) are a good way to leverage non-ultra poorbeneficiaries to support pro-poor development. Correct selection and adequate training of PIC members, oversight and monitoring are required to ensure quality and accountability in project implementation by communities. 7. Focus on gender mainstreaming: Any project needs to consider whether the project benefits gained by women outweigh activities that add to their heavy work burden. Gender sensitization for all community members (male/female, ultra-poor/non-ultra-poor) helps to enable project gender mainstreaming. Exogenous factors beyond the project mandate which can hamper the implementation of gender strategies should be identified and considered. 8. Build local capacity and overcome gender bias by engaging local leadership: Strong emphasis on capacity building at all stakeholder levels, including government line officers and also local administrators not only at the community level but also zonal/district levels. 9. Mainstream climate change and disaster risk management: Disaster risk management committees are more effective if the principles of inclusiveness and diversity (male/female, ultra-poor/non-ultra-poor) are considered. 10. Effective partnership model contributes to project results: Effective communication, networking and advocacy require strategies, mechanisms, budgets and human resources. The capacity of potential partners needs to be assessed and, if required, strengthened. 11. Build a robust monitoring system to track milestones and results: Ensure GSMART (gender disaggregated, sensitive, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) indicators to track outputs, immediate (knowledge and attitude) and intermediate (behavioural change and practice) outcomes. Conclusion Ideally, an ex-post project evaluation could be undertaken a few years after the cessation of the project to assess the level of resilience of beneficiary households. Ultimately, behavioural change and practice will determine how resilient the communities have become in the face of climate change.