Merlin Policy Paper on Advocacy

advertisement

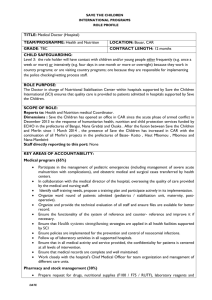

Field-Based Humanitarian Advocacy A Concept Paper for Merlin By Cynthia Scharf January 2003 Scharf Draft 1/03 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Humanitarianism and Advocacy 2.0 What is Advocacy? 3.0 Why Engage in Advocacy? 3.1 Humanitarian Principles 3.2 Humanitarian Practice in Context 4.0 What are the Benefits and Risks of Advocacy for Merlin? 4.1 Benefits 4.2 Risks 5.0 What Issues does Merlin Advocate On? 5.1 Key Principles 5.2 Identifying Violations 5.3 International Humanitarian Law (IHL) 5.4 Sphere Humanitarian Charter 5.5 Issues of Humanitarian Access under IHL 6.0 From Ideas to Action: Advocacy Issues in the Field 6.1 Providing and Receiving Humanitarian Assistance 6.2 Violence Against Civilians 6.3 Population Movements Within the Country 6.4 Population Movements Across International Borders 6.5 Attempts to Limit Humanitarian Independence 6.6 Violence Against Humanitarian Staff and Property 7.0 How to Collect Information for Advocacy Purposes 7.1 Who Collects It? 7.2 How is it Collected? 7.3 Access and Storage 8.0 From Information Gathering to Advocacy 8.1 Who Decides Whether or Not to Advocate? 8.2 Criteria for Engaging in Advocacy 8.3 Security Precautions 8.3.1 Safety of Beneficiaries 8.3.2 Safety of Merlin Staff 8.3.3 Communications 9.0 Types of Advocacy 9.1 Private 9.2 Semi Private 9.3 Public 10.0 Target Audiences 10.1 Local and National Authorities 10.2 International Institutions 10.3 Donor Governments 2 Scharf Draft 1/03 10.4 Corporations and International Business 10.5 Mass Media and the Public 11.0 Designing an Advocacy Strategy At the Field Level 11.1 Possible Courses of Action 11.1.1 At the Private Level 11.1.2 At the Semi-Public Level 11.1.3 Public Action 11.2 Guidelines 11.2.1 Identify the Problem and Propose Desired Changes 11.2.2 Make Yourself Heard 11.2.3 Follow Through 12. Advocacy at Merlin Headquarters 12.1 Criteria for Undertaking Advocacy 13.0 Designing an Advocacy Strategy At Headquarters 14.0 Final Comments on Advocacy and Assistance Appendices 1.0 Additional Resources 2.0 Reference Documents 2.1 International Human Rights Law 2.2 International Humanitarian Law 2.3 Principles of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Response 2.4 Sphere Humanitarian Charter 3.0 Sample Witness Statement Form 3 Scharf Draft 1/03 Field-Based Humanitarian Advocacy A Concept Paper for Merlin 1.1 Introduction The goal of this document is to provide Merlin staff with the tools needed to conduct field-based advocacy in support of our beneficiaries’ security and well-being. This paper obviously does not presume to forecast the details of every advocacy situation that might arise in the field. Instead, it provides some basic concepts, principles and guidelines, which local field offices can use and adapt to their specific circumstances. 1.1 Humanitarianism and Advocacy Merlin stands in solidarity with those who suffer from war, violence, disease, disaster and deprivation and are in need of timely medical assistance. As a humanitarian organisation, Merlin subscribes to the fundamental principles of impartiality, independence and neutrality that are the foundation of our work. Merlin’s mandate is to provide medical assistance to populations at risk. In and of itself, however, such assistance is an insufficient response to human suffering when the lives and physical security of those whom Merlin assists are in jeopardy. We reject the complicity of silence that enables perpetrators to commit acts of violence and intimidation against civilians in a climate of impunity. In cases such as these, Merlin believes it is our obligation as humanitarians to address those external conditions that imperil our beneficiaries and render our assistance necessary in the first place. For Merlin, advocacy emanates from a position of medical ethics and humanitarian imperative. We are not lawyers or human rights specialists, but medical professionals who feel a moral obligation to bear witness to the suffering of those whom we serve.1 We believe that all civilians have a right to protection and assistance, and we commit ourselves to uphold these rights in accordance with the principles of the Geneva Convention and the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Advocacy represents a tool by which to link relief and protection activities into a cohesive operational framework. Merlin’s advocacy efforts are driven by the needs of its beneficiaries and undertaken with their security and well being our first priority. At all times, our primary accountability is to those whom we serve. Through advocacy, we call upon the relevant authorities to uphold their obligation under international law to protect and provide for civilian populations. We also advocate for the right of humanitarian actors to access and assist these populations in order to satisfy their basic right to life with dignity. Advocacy compliments Merlin’s core work in medical assistance by offering another means of alleviating the suffering and protecting the physical security of our beneficiaries. Through advocacy, Merlin can address the very conditions that make its aid necessary in the first place, including access and protection issues that are central to its relief activities. 1 See, for example, Merlin’s Code of Conduct for Individuals 4 Scharf Draft 1/03 Silence on the part of international agencies in the face of ongoing abuses represents complicity with the aggressors and a betrayal of victims’ right to assistance. In rejecting this stance, Merlin stands in solidarity with the victims of suffering, and will advocate on their behalf when their lives, security and physical well-being are threatened. 2.0 What is Advocacy? Definition: Advocacy is using information in a strategic manner to make arguments seeking to change the policy or practices of local or national authorities, governments, parties to an armed conflict, international institutions, corporations, donors and/or the public at large. The foundation of Merlin’s advocacy work is current, verifiable information from the field in the form of medical data, interviews of patients and other interlocutors, the testimonies of staff and patients, as well as field knowledge acquired by Merlin staff. Objective: In all cases, Merlin’s goal in utilising advocacy is to better protect and assist its beneficiaries, e.g., civilian populations who suffer from violent conflict, disease, disaster, displacement, and/or violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. Oftentimes access to vulnerable populations is blocked, violating international law and putting the lives of civilians at risk. Increasing access to populations in need will be a key objective of our advocacy efforts. Focus: The audiences, messages, and methods of Merlin advocacy will vary depending on the objectives Merlin sets for itself. In all cases, however, Merlin’s advocacy efforts will be beneficiary-focussed, eschewing broad thematic or global campaigns to focus on the specific humanitarian and protection needs of those whom it serves. Merlin will not endeavour to address human rights concerns that go beyond the principles, practices and rights accorded to it under international humanitarian law. This being said, Merlin reserves the right to speak out when egregious violations of the principle of humanity – genocide, torture, extra-judicial killings, disappearances – impel it to bear public witness as a humanitarian organisation. Improving the safety and well being of populations at risk is the focus of Merlin’s advocacy efforts. Advocacy is undertaken for the purpose of protecting the life and improving the security, health and basic human rights of Merlin’s beneficiaries, and promoting respect for the principles of independence, impartiality and neutrality that guide its work. 3.0 Why Engage in Advocacy? Both principles and practical realities underscore the need for advocacy. 3.1 Through advocacy, Merlin seeks to advance the fundamental humanitarian principles that underlie its assistance programs: Humanitarian principles: 5 Scharf Draft 1/03 1. Independence – The independence of humanitarian actors is under increasing threat of ‘mission creep’ by western militaries espousing the oxymoronic idea of ‘military humanitarianism’. Merlin rejects this fallacious concept and will continue to push for the strict separation of politics from humanitarian activities. Merlin’s advocacy in this area will stress the need for complete operational independence from political pressures exerted by donors, governments and/or militaries. Merlin strictly repudiates any efforts to induce it to act as a tool of any government’s foreign policy. 2. Impartiality – Merlin has a humanitarian obligation to provide assistance wherever it is most needed. Obtaining unimpeded access to at-risk populations is therefore of fundamental importance to Merlin’s operations, and will constitute a key focus of Merlin field-level advocacy. 3. Neutrality – In advocating on behalf of the victims of suffering, Merlin will continue to maintain a stance of strict neutrality. 3.2 Practical Context: The context in which humanitarian agencies operate today is more fluid, chaotic and dangerous for our beneficiaries as well as staff. Advocacy has become an increasingly important tool of humanitarian engagement as a result of changes in the international arena. 1. The proliferation of non-state actors (local militias, rebel armies, terrorist cells, separatist groups): In many cases, these actors do not adhere to or uphold the tenets of international law. Many of the conflicts that spark humanitarian crises (Congo, Ingushetia, Somalia, Sierra Leone, Angola, etc.) involve these poorly defined, fluidly configured non-state actors. Their understanding of humanitarian principles, as well as their own obligations to civilians under international law, is poor at best. At worst, they actively obstruct or target humanitarian agencies operating under in their areas of control. In this context, advocacy is necessary to educate/inform all parties to a conflict of their obligations under international law to protect and provide for non-combatants. 2. Displaced populations: The existence of some 39 million displaced persons in the world today means that huge numbers of civilians exist in a grey area of international law in which it is unclear who assumes responsibility for their protection and provision of basic assistance. Humanitarian agencies can help publicise the conditions in which these displaced persons live, and point a finger toward local and national and international authorities to provide for their basic needs. 3. Civilians as the primary victims: The Geneva Conventions stipulate that during periods of armed conflict, non-combatants are to be protected and treated humanely in all circumstances. Sadly, this basic principle of international humanitarian law has been violated repeatedly in modern warfare. Civilians, rather than non-combatants, are by far the greatest casualties of today’s conflicts, with women and children constituting the primary victims. Given this context, advocacy focused on the physical protection and basic physical and mental well being of civilians is increasingly imperative. For Merlin, such advocacy forms an integral part of its humanitarian mission as stipulated under international humanitarian law. 4. Challenges to humanitarian independence: The US-led ‘war on terrorism’ threatens to compromise further the operational independence of humanitarian agencies. The encroachment of military and political actors on what has been 6 Scharf Draft 1/03 termed “humanitarian space” began in Bosnia and developed apace in Kosovo and Afghanistan. Humanitarian agencies must strictly separate themselves from the aims and operations of any military intervention, and adamantly reject any insinuation that agencies might serve as a ‘force multiplier’ for donor governments. Advocacy on behalf of the principle of humanitarian independence is an increasingly necessary responsibility for all humanitarian organizations, especially those like Merlin who are based in countries that may well be parties to a conflict. 5. Selective adherence to international law: The ‘war on terrorism’ is also undermining attempts to uphold international humanitarian law (IHL), which was designed to protect civilians from the worst excesses of war. IHL also outlines our rights and responsibilities as humanitarian actors in situations of conflict. The ‘war on terrorism’ has legitimized a selective adherence to IHL and subordinated legal guarantees for civilians to the overall aims of military forces, which have hid behind the anti-terrorism label while committing abuses (in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Israel, Pakistan, and China, for example). 4.0 What are the Benefits and Risks of Advocacy for Merlin? 4.1 Benefits Advocacy challenges the causes of humanitarian suffering in addition to the 4.0 ymptoms by advocating for greater protection and access to populations in distress. Emergency assistance only goes so far if the life that is saved is in continued peril due to the absence of adequate protection. Advocacy derives from and compliments Merlin’s programme experience. It provides us with a tool for making a more sustainable improvement in the security, health and well being of our beneficiaries. Advocacy can increase Merlin’s profile with local and national authorities and bolster chances of negotiating access to vulnerable populations. Advocacy can help build local partnerships in the field, while aiding in the creation of NGO coalitions and contacts in the west. Advocacy can contribute to a more informed and engaged constituency, and has the potential to heighten Merlin’s profile among donors, NGOs, and the public. As the U.K.’s only medical relief agency, Merlin is in a unique position to affirm publicly to a British audience (donors, lawmakers, the public) the principles of independence, impartiality and neutrality that are the foundation of Merlin’s work as a humanitarian agency. If Merlin fails to advocate on a specific issue, it might damage its credibility (e.g., if it failed to speak out about genocide, massive abuses or refoulement policies carried out on its direct beneficiaries). 4.2 Risks If advocacy creates the perception that Merlin is no longer neutral, local parties to a conflict could restrict or hinder access to vulnerable populations. Potentially Governments/rebel factions could construe advocacy as a breach of Merlin’s neutrality in a local conflict. This could lead to greater security risks for Merlin’s beneficiaries as its field staff, particularly national staff. 7 Scharf Draft 1/03 Merlin could be expelled from a region or country. In either case, Merlin would fail to reach those who need assistance. If local parties to a conflict believe Merlin is collecting evidence/testimony that could be used against them (documentation of killings, rapes, other abuses), then Merlin staff and/or its facilities could be targetted for retaliation. Advocacy could divert scarce resources (especially staff time) away from the direct provision of medical relief. At present, no staff is assigned specifically to advocacy within Merlin headquarters. Any follow-up to field level advocacy will be the responsibility of already over-burdened desk officers or the communications department, which is not yet set up to co-ordinate advocacy work. 5.0 What Issues Does Merlin Advocate On? In general, Merlin field staff will initiate advocacy on concerns that arise from humanitarian principles (impartiality, independence, neutrality and humanity) and violations of international law (humanitarian law or the ‘law of armed conflict’; refugee law, and human rights law).2 First, a few words about our approach. Merlin is a humanitarian organisation guided by a set of fundamental principles enshrined in international law (specifically, humanitarian, human rights and refugee law). We are humanitarians first and foremost, medical professionals, not lawyers or human rights specialists. In advocating on behalf of those who suffer, we do not pretend to be knowledgeable in the fine points of international law. We serve on the frontlines of human suffering, not in the hushed hallways of the barrister’s courtroom. Our advocacy efforts emanate from a moral stance, not a legalistic one. As humanitarians, our advocacy is driven by the need to express solidarity with our beneficiaries; it is driven by compassion and a sense of moral outrage at the oftentimes-inhumane conditions in which they live. We cannot halt the abuses we witness, but through our advocacy, we can call upon those who are responsible – governments and all other parties to conflict – to uphold their obligations under international law to protect and provide for the human treatment of all non-combatants. 5.1 Key Principles: Beneficiaries first -- At all times, protecting the life, security, and well-being of our beneficiaries is our first priority. Our goal is to make things better, not worse, for those whom we are seeking to help. We must first ask ourselves if our advocacy could expose beneficiaries to greater risks, and if so, seek alternative means of assistance. Protect your sources (see below for details) Stick to humanitarian principles, not politics – Merlin is an impartial, nonsectarian organization. We do not take sides or offer commentary on a conflict, nor do we propose political solutions. Our mandate is to ameliorate the humanitarian consequences of political failures. At the same time, our 2 See reference documents on international human rights and humanitarian law cited in the appendices. These documents can be accessed via the ICRC’s website: www.icrc.org 8 Scharf Draft 1/03 humanitarianism should not be used as a convenient fig leaf for government inaction or a substitute for political engagement. Stay focused – Merlin’s advocacy should be driven by our medical relief programmes and in most cases, focus on information obtained from or pertaining to health concerns. Exceptions to this are obvious cases of abuse and violence as well as egregious violations of international humanitarian law (see below for details) Do the right thing-- As humanitarians, we speak from a position of moral concern, not from specialised legal or political expertise. If you don’t know for certain if something is illegal -- but you know it’s wrong -- then go with your gut. Talk to your colleagues and work out the best plan of action to ensure your beneficiaries’ well being. 5.2 Identifying Violations3 Advocacy begins with identifying the problem that needs to be addressed. For Merlin, these problems generally can be identified by asking the following questions: Are there humanitarian principles that are being violated or compromised? Are there obvious or repeated violations of international law? Are civilians at immediate grave risk? First of all, how do we know what constitutes a violation of humanitarian principles or international law? We are medical professionals and humanitarians, not lawyers, guided by a moral compass that directs us to action. That compass’s basic points of reference are located in provisions of international law (humanitarian, human rights and refugee law), the Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement in Disaster Relief (1994) and the Sphere Humanitarian Charter.4 5.3 International Humanitarian Law (IHL) IHL only applies during armed conflicts (domestic rioting or acts of sporadic violence are not considered armed conflict) and differentiates between internal (civil wars) and international conflicts. Significantly, IHL mandates that rules for the minimum humane treatment of non-combatants apply equally to all sides of a conflict, governments as well as armed insurgent groups, regardless of who started the fighting. Neither side needs to have signed the Geneva Conventions for these rules to apply, nor does the insurgent group have to be officially recognised. IHL provides protection to certain categories of persons considered non-combatants, which includes civilians, prisoners of war, and wounded, sick and shipwrecked soldiers. Among these are: 3 Merlin gratefully acknowledge the contributions of MSF-Holland to the sections on humanitarian law, the reporting of violations, and numerous other insights that inform this document throughout. MSF-Holland’s contributions are taken from a manual on witnessing and advocacy prepared by its Humanitarian Affairs Department. These documents can be accessed from ICRC’s website (www. icrc.org/eng/party/_gc) or the reference section of the Overseas Development Institute (www.odihpn.org) See appendix for a detailed list of recommended reading and reference documents. 4 9 Scharf Draft 1/03 All wounded should be cared for; Medical personnel are protected persons. No one may be punished for carrying out medical activities compatible with medical ethics, nor be compelled to carry out acts contrary to medical ethics; In an international armed conflict, all captured combatants (prisoners of war) shall be treated equally; have adequate conditions of captivity and be entitled to inform their relatives; POWs shall be allowed visits by the ICRC; Starvation of civilians as a method of warfare is prohibited. It is forbidden to attack, destroy, remove or make useless objects indispensable to the survival of civilians, such as crops, livestock, and water supplies. 5.4 Sphere Humanitarian Charter In addition to specific provisions of international law, Merlin abides by the Sphere Humanitarian Charter, which is founded on the following principles: 1. The right to life with dignity – this includes the right to receive life-saving assistance and to live free of threats to one’s personal security. It further entails a responsibility to protect and preserve life when it is threatened. 2. The principle of non-refoulement – no forcible repatriation of any refugee if his/her life, safety or freedom would be threatened. 3. The distinction between combatants and non-combatants – this distinction forms the basic principle of international humanitarian law (IHL), which is codified in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their two additional protocols. The Conventions designate the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as the official monitor of how IHL is implemented. Any questions about IHL should be addressed to the ICRC. 5.5 Issues of Humanitarian Access under IHL IHL gives humanitarian personnel the ‘right of initiative’ to offer their services during an armed conflict. While this right does exert moral pressure on a state to accept assistance, it does not allow Merlin to provide humanitarian assistance without the consent of the parties involved. In other words, to access civilian populations at risk, Merlin (and all other agencies) must obtain the consent of the parties to a conflict. States may invoke national sovereignty to prevent humanitarian aid from entering their territory. A state that refuses to allow needed humanitarian assistance, however, may be violating the basic international human right to an adequate standard of living. Prohibiting aid in a manner that threatens the life of its intended recipients could be considered a violation of the right to life. Under IHL, access may properly be denied if a state or party to a conflict can show that aid is not provided impartially for humanitarian purposes. Access can also properly be denied for urgent security reasons, though it may not be denied for longer than is necessary. 10 Scharf Draft 1/03 6.0 From Ideas to Action: Advocacy Issues in the Field Merlin’s advocacy is driven by our overriding concern for the safety, health and wellbeing of those whom we assist. Identifying violations of international law or humanitarian principles should not be an academic exercise, but one that is directly relevant to our beneficiaries’ basic needs. To simplify the task, we have highlighted below situations commonly encountered in the field in which humanitarian principles and/or international law are threatened.5 Merlin staff should carefully record what they witness during these situations according to the guidelines listed later in this document (see section on “How to Gather Information”) The examples below break down into six basic situations: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Providing and receiving humanitarian assistance (issues of access) Violence and indiscriminate attacks on civilians Population movements within borders (IDPs) Population movements across borders (refugees) Violence against humanitarian staff and property Attempts to limit humanitarian independence 6.1 Providing and Receiving Humanitarian Assistance Obtaining access to populations in need is one of Merlin’s prime objectives. Access can be restricted for a variety of reasons (bureaucratic, political, military.). Even if access is granted, aid can fail to reach its intended recipients due to corruption or threat of violence to beneficiaries. This section taken from MSF-Holland’s manual for witnessing and advocacy, which was prepared by its Humanitarian Affairs department. 5 11 Scharf Draft 1/03 Providing and Receiving Humanitarian Assistance Take Notes and Keep Records when … Official restrictions are placed on access to the country, such as refusal of visas, improper customs duties, prohibitions on necessary equipment. Access to specific areas is denied (note if a demand for fees or threats accompany such refusals) Assistance is blocked by government forces or other forces Relief assistance is diverted or cannot be properly monitored Payment and/or sexual favors is demanded of those receiving aid that is distributed by local authorities, militias, etc. Those in need have difficulty reaching you (note why and how: harrassed, threatened, too weak to travel, etc.) 6.2 Violence against Civilians Under international law, civilians and civilian populations should never be the object of a military attack or threats of violence intended to spread terror. Civilians shall not be subject to reprisals. Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited. Civilian casualties can only be excused if they are incidental to an attack on a military target provided that all precautions have been taken to protect civilians. VIOLENCE AGAINST CIVILIANS Take Notes and Keep Records When … Possible human rights violations of which you have personal knowledge, including physical violence, unlawful arrests and detention and infringements of the freedoms of expression, association, assembly and religion. Persons come to you having suffered violations of their human rights, or when they are afraid their rights will be violated. the information cannot immediately be verified. Persons are able to describe violations against others of which they are personally aware. Cases of an urgent nature (threat of killing or torture, “disappearances,” etc.) even when 12 Scharf Draft 1/03 6.3 POPULATION MOVEMENTS WITHIN THE COUNTRY Displacement of civilians during armed conflict is allowed only when their security is jeopardized or for urgent military reasons. When the safety of civilians is at risk, parties to a conflict are themselves obligated to displace civilians from combat zones and move them to safer areas. Displacement must be for genuinely necessary military reasons, and not for political reasons (i.e., attempts to control minority populations). During displacement, civilians must be provided with satisfactory shelter, hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and all measure should be taken to keep family members together. Under international law, the state retains primary responsibility for IDPs within its terrority by virtue of the principle of sovereignty and non-intervention. Population Movements within the Country Take Notes and Keep Records When … IDPs are mistreated by government or other authorities in their camps. IDPs in a camp are quarantined or otherwise treated differently from others in the group. IDPs are denied access to basic food, shelter or health care, or payment is demanded by parties to a conflict for humanitarian assistance that was provided free of charge by aid agencies. IDPs are going to be transferred from one locale to another by government or other forces. Inquire why they are being moved and the manner in which they are treated. Are they being adequately provided for? 6.4 POPULATION MOVEMENTS ACROSS INTERNATIONAL BORDERS Under international law, refugees are to be protected from refoulement (forcible return to any country where one is likely to face extreme danger, persecution or torture; for example, the refoulement from Ingushetia back to Chechnya of Chechen refugees). In special circumstances, usually related to national security reasons, states retain the power to limit refugees’ freedom of movement. The fundamental rights of refugees and displaced persons nevertheless are to be respected; for example, they cannot be subject to arbitrary arrest or detention. When a mass influx of refugees occurs (as in Zaire in 1994 after the Rwandan genocide), states sometimes have decided to house refugees in closed or restricted camps. In these cases, it is imperative that humanitarian agencies be afforded access to refugee and at-risk populations. Population Movements Across International Borders 13 Scharf Draft 1/03 Take Notes and Keep Records When … Refugees (and displaced persons) are mistreated by government or other authorities in their camps. Refugees are threatened with refoulement (forced return to their country of origin). Persons not entitled to refugee status (e.g. war criminals and other violent criminals) are exercising control over the refugees or their camps Some refugees in a camp are quarantined or otherwise treated differently from others in the group. Refugees are going to be transferred from one locale to another by government or other forces. Inquire why they are being moved and the manner in which they are treated. Are they being adequately provided for? A voluntary repatriation plan is being devised by government authorities, international organisations, or the refugee themselves. Is sufficient information being provided as to the conditions in the home country? 6.5 ATTEMPTS TO LIMIT HUMANITARIAN INDEPENDENCE Military peacekeeping forces have become an increasingly common presence in many of the areas Merlin works, raising questions about the degree to which humanitarian agencies, military forces and the local population interact. Governments (in particular, their military and intelligence wings) often have an active interest in the information Merlin collects in the field, and/or recruiting personnel. As the line between military and civilian intervention becomes increasingly muddied (Kosovo, Afghanistan, and likely Iraq), humanitarian agencies including Merlin face the risk that one of their key principles – independence of action – will be compromised. Merlin is a signatory to The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement’s Code of Conduct, which states unambiguously that: “We (NGOs)…formulate our own policies and implementation strategies and do not seek to implement the policy of any government, except in so far as it coincides with our own independent policy. We will never knowingly – or through negligence – allow ourselves, or our employees, to be used to gather information of a political, military or economically sensitive nature for governments or other bodies that may serve purposes other than those which are strictly humanitarian, nor will we act as instruments of foreign policy of donor governments.”6 In Afghanistan, among other places, humanitarian aid workers have been mistakenly confused with members of the armed forces who, out of uniform, provided some form of material assistance to the local community. Any confusion on the part of the local Article four of the “Principles of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement” and NGOs in Disaster Response Programmes. All Merlin staff are expected to have read and signed this Code of Conduct. 6 14 Scharf Draft 1/03 population in distinguishing between soldiers and aid workers means humanitarian personnel are potential targets of military action. Limits on Humanitarian Independence Take Notes and Keep Records When … Attempts are made by military or intelligence officials to solicit information on Merlin’s operational activities (other than general information on transport safety, airport closures, overall security situation, etc.) Attempts are made to recruit Merlin staff for intelligence purposes. Members of the armed forces are not clearly identified (i.e., wearing uniforms or displaying military identification) while providing some form of material assistance to civilians (e.g., food distribution). 6. 6 VIOLENCE AGAINST HUMANITARIAN STAFF AND PROPERTY Humanitarian workers and their property are protected by national laws, relevant provisions of international human rights law and special provisions that may be provided under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between a host government and Merlin. Humanitarian law provides that medical and relief workers have the right to be “respected and protected” during periods of armed conflict and receive humane treatment, as do all other non-combatants. In internal armed conflicts, formal legal protections for humanitarian workers are significantly weaker. They basically have the same rights as other non-combatants. Violence Against Humanitarian Staff and Property Take Note of and Keep Records When … Any threat, or possible threat, has been received by your office or any individual member. A member of your office has been harassed, threatened with arrest or the target of violence by the authorities (or other group). You receive information that suggests that your office or that of another humanitarian agency might be the target of attack. 15 Scharf Draft 1/03 7.0 How to Collect Information for Advocacy Purposes Merlin’s advocacy derives from the accurate, timely, and readily accessible information gathered in the field from verifiable sources. The types of information used may include medical information (e.g., nutritional surveys), witness accounts, interviews with victims of violations, photographs/video, and physical and forensic evidence. Information should verifiable. Do not leap to general, sweeping conclusions based on specific, isolated incidents. Instead, look for patterns of abuse and/or violations; repeated incidents are more likely to substantiate broad conclusions. As mentioned earlier, our first concern in advocacy is the safety of those whom we are there to assist with medical relief. We are there to help – not to make matters worse. The interests of our beneficiaires must always come first; never undertake any action that would harm them or jeopardize their security unnecessarily. 7.1 Who Collects this Information? Merlin field staff -- primarily expatriate personnel, for security reasons -- should collect evidence of specific violations or breaches of humanitarian law and principles. The information should be based on the staff member’s direct witnessing of an incident, or the eyewitness testimony of someone the staff member has spoken with. 7.2 How Is it Collected? All information should attempt to answer the basic 4 W’s: Who, What, When, and Where, as well as How. (The “Why” is best left for another forum). Information should be standardized for ease of use. A sample data collection form is attached as an appendix. In situations where tensions are running high and Merlin and/or its beneficiaries fear the threat of reprisal, information should be recorded privately. In general, do not antagonize parties to a conflict by taking out pen and paper or a camera and recording incriminating information in a publicly confrontational manner. A public approach should be used only when all other means of private, direct advocacy have been tried; if the evidence is so horrific that it demands public witnessing (evidence of a massacre, for example); and/or if the immediate security of civilians is at stake. Again, take extra care to remove any names or personal data that might identify and hence endanger victims or witnesses. Some agencies use a system of codes for identification purposes. 7.3 Access and Storage of Information: Information is valuable for advocacy purposes to the extent it is accessible and can be acted upon quickly. Data collected by Merlin staff on humanitarian/human right violations should be stored in a format that is standardized and readily usable (standardized data sheets, word files; jpeg files, etc.). In particular, witness information gathered from beneficiaires should be kept in a safe, secret place. Files (paper or electronic) should not be kept in the Merlin field office for obvious security reasons. Merlin’s Country Director (CD) should know where the files are kept and have access to them at all times. On a monthly basis (or more frequently depending on tensions in the area) CDs should read through data collected by the field staff pertaining to the five situations above. The CD and relevant staff members should then assess the situation on the ground to see if and how some form(s) of advocacy could improve conditions for our 16 beneficiaires. In particular, be alert to any patterns of repeated violations and/or egregious abuses that require urgent action. 8.0 From Information Gathering to Advocacy Identifying a violation of international law or witnessing specific abuses against civilians (as cited in the examples above) is only the first step. Deciding what to do with this information is crucial, and involves numerous considerations; again, first and foremost, the safety and well-being of those whom we are trying to help. Since we do not presume to anticipate every situation that might arise and lend itself to advocacy, the following comments are simply a guideline listing the types of questions and criteria that field offices might consider. Emergency or Urgent Information: If a Merlin staff member hears and records information indicating someone’s life is at immediate risk or otherwise in serious danger, he/she should promptly notify the Country Director. A course of direct action should then be undertaken. If the Country Director is not available, his/her deputy should be informed. If a civilian has been detained, try to ascertain his/her whereabouts and if possible, visit him/her, bringing a doctor with you. Merlin personnel should not travel to detention centers, military bases, or police stations alone. 8.1 Who Decides Whether or Not to Advocate? After reviewing all available information, Merlin CDs will decide if and how to advocate in a given situation. Field level advocacy on particularly sensitive issues (from the point of view of politics, donors or extreme emergencies, for example) must be coordinated with the Merlin London office. The relevant Ops Desk Officer is the first point of contact in London. 8.2 What Are the Criteria for Action? The following issues should be considered before deciding whether to take action: Violations of Humanitarian/Human Rights Law How serious and/or urgent are the violations, and to what extent do they represents a pattern of abuse versus an isolated incident? To what extent do the violations directly affect Merlin’s work, programmatic goals, or medical ethics? Have the existence and extent of the violations been established by reliable and verifiable sources? Risks7 What are the risks to the local population of taking action versus not taking action? What are the risks for Merlin staff – in particular, members of the national staff who are always at greater risk for retaliation on the local level? If Merlin does not advocate, would that damage its credibility with beneficiaries and/or the humanitarian community? 7 See the section below on special security precautions. 17 Is engaging in advocacy going to drain critical resources (staff, time) from necessary medical activities? Is engaging in advocacy putting Merlin’s operational activities in a given area/country at risk? What Can Be Achieved What possibility is there that our advocacy will achieve the desired goal? Does Merlin have the knowledge or experience to propose a feasible solution? Does Merlin have some unique, distinctive contribution to bring to the table (new or relevant medical evidence, inside contacts, a fresh angle to the issue) that other NGOs or actors do not have? 8.3 Security Precautions 8.3.1 Safety of Beneficiaries: Before undertaking any and all advocacy, Merlin staff must first determine if any risks to its beneficiaries and/or staff could result. Safety for the victims of abuse and their families8 1. When gathering information for possible advocacy, make sure those interviewed understand why you are meeting with him or her. Explain what you are going to do with the information. (Will the information be publicised or not? What information about the victim will be used?) 2. Sometimes victims and families want information about their case publicised. At other times, they want to keep the information quiet because they fear additional problems. In general (but not always), those at risk are the best judges of the danger they face. 3. Only publicise information about a specific case if the person or their family agrees. This is not necessary if the case has already received public attention and if you can be sure no additional harm can come to the victim or their relatives by publishing it. 4. Sometimes victims and families will allow the information about a case to be made public if names or other identifying information is left out (such as village or date where event occurred). You can sometimes use pseudonyms; give only a partial description of the place or a general date. 5. Sometimes a victim or their family will permit you to use their names publicly when you believe it is not safe to do so. It is better to err on the side of safety. 6. Be very careful with your notes and other documentation. In sensitive cases use codes for names and keep the real names in a separate place (or commit them to memory). 8 This information provided courtesy of MSF-Holland’s manual on witnessing and advocacy. 18 8.3.2 Safety of staff: As mentioned above, national staff is at greater risk of reprisal or violent measures if and when advocacy is undertaken. CDs should ensure that national staff are informed of whatever advocacy measures are taking place at the field level, and take appropriate measures to safeguard their well being (including staff rotations if necessary). 8.3.3 Communications: Witness reporting statements and other logged information used for advocacy purposes should be treated as confidential.9 CDs should have procedures in place for safely logging, storing, and transmitting (through secure lines if necessary) sensitive information. CDs, in conjuction with London HO, will decide whether advocacy information should be shared with external agencies depending on the objectives, risks and benefits of doing so. 9.0 Types of advocacy Advocacy can take many forms and draw on several methods at once. Most people tend to think of advocacy as a highly public activity, at times verging on rhetorical grandstanding. This very visible form of advocacy is, in fact, the least common and least likely advocacy Merlin will engage in. At all times, our advocacy seeks to bring tangible improvements to the lives of those whom we are seeking to assist. Advocacy can take place on several levels: private, semit public and public. In general, the most common form of advocacy that Merlin engages in takes place at the field level through private, direct advocacy with local interlocutors. 9.1 Private – sometimes called ‘silent diplomacy,’ meaning direct contact with interlocutors (Ministry of Health, Interior, Justice, other local, regional and national authorities, rebel leaders, parties to a conflict) through personal discussions, letter, etc. A key question is who to approach and at what level of authority. All contacts between officials and Merlin staff, as well as the outcome of those contacts, should be logged in the data collection forms. 9.2 Semi-private – Advocacy can be conducted in collaboration with other NGOs and/or medical forums. Merlin information can also be passed on quietly to donors, other international agencies, or human rights groups working in the area. Similarly, information might be given – for non-attribution only – to trustworthy members of the media. Again, Merlin field offices should maintain a written record of all such contacts even if they are done as third-party advocacy efforts. 9.3 Public – In cases of repeated abuse or egregious violations of international law, Merlin may choose to issue public statements or position papers, approach members of the media for attribution, and/or overtly lobby government officials. CDs must approve any public advocacy initiatives and coordinate such efforts with Merlin headquarters. As a last resort, Merlin may decide to suspend or close down a program or withdraw from an area altogether if it decides that (1) the safety of the population and/or the staff is seriously threatened; (2) its very presence lends unwanted credibility to the 9 See appendices for an example of a witness reporting form. 19 perpetrators of violence, leading to the perception that Merlin is a silent accomplice to their violations. 10.0 Target Audiences Target audiences for an advocacy initiative will vary depending on the issue and objectives in question. 10.1 Local and National Authorities. A key focus of Merlin’s field advocacy is to improve access to populations at risk. The most relevant audience for this kind of advocacy is local authorities at the municipal, regional and/or national levels. Merlin might also advocate on behalf of improvements in safety and living conditions for beneficiaries, register its protest over the illegal movement of civilian populations, violence or threats against the beneficiary population or its own staff. It also may be beneficial to join with other NGOs and/or local partners to advocate on these issues. (Field office) 10.2 International institutions (UN agencies, etc). – Advocacy can be used to register violations of international law and seek redress/apply pressure to stop abuses. (Field and/or London office) 10.3 Donor Governments – Field and possiblMerlin can utilize the principle of impartiality (assistance based on need) to advocate with donors for greater resources and/or protection for vulnerable populations (in particular, those threatened by ‘silent emergencies’). Merlin could also collaborate with other NGOs to advocate for greater funding in a CAP (Consolidated Agency Appeal) for a given population or area. (Field and/or London office) 10.4 Corporations and International Business – Advocacy could be employed to apply pressure to improve health and protection of civilian populations living near and/or affected by corporate operations, or to register violations of international law conducted by corporate entities. (Field and/or London Office) 10.5 Mass media and the public – Public advocacy would draw attention to grievous violations of international law witnessed in the field by Merlin, and attempt to focus greater international political pressure on violators to desist. Given Merlin’s limited resources and mandate, this kind of high profile advocacy, coordinated from the London office, is not something Merlin expects to engage in frequently. (London office) 11.0 Taking Action: Designing an Advocacy Strategy for the Field Merlin’s field staff is likely to encounter numerous injustices and violations of international law in the course of their work. Merlin cannot take on each issue, nor should it try to do so. We must be realistic and concentrate our energies where we can hope to make a tangible, positive difference for our beneficiaries. A An advocacy startegy begins with identifying the problem at hand based on verifiable, timely information recorded by field staff. After clearly stating the problem, the next step is to identify the goal or changes desired to solve the problem. Begin by choosing 20 goals that are achievable – changes in routine practices, policies, administrative orders, rules, etc. that directly affect our beneficiaries health and safety. Make sure you have the information needed to back up your arguments. The existence of credible information recorded in a logbook is absolutely central to any advocacy effort. 11.1 Possible Courses of Action The most common course of action will likely be conducted at a private level. Merlin will advocate with local interlocutors, seeking tangible changes in policy or practices that directly affect our beneficiaries. In general, Merlin’s advocacy is best initiated at this low profile level. Higher visibility approaches are appropriate only if the results from private forms of advocacy are not forthcoming. Emergencies, or incidences of extreme violation of international law, are obvious exceptions to this rule and require urgent public action. The following are among the possible courses of action for field-level advocacy10: 11.1.1 At the private level: Oral or written communication with relevant authorities or decisionmakers. This could include local militia and military commanders, camp authorities, police and interior officials, municipal and national leaders, international representatives, donor representatives, corporate or business leaders. Remember that whom one contacts can be more important than what is actually said. Enlisting the support of other community leaders or local NGOs to influence these decision-makers 11.1.2 At the semi-public level: Passing on information collected by Merlin to other trusted organizations: human rights groups (Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Physicians for Human Rights) or International Institutions (OSCE, UNHCR, ICRC). All such exchange of information must be approved by the CD, who will notify the London office. Information can also be passed along through the London office, not at the field level, if security requires. Passing on information – Not for attribution, but on background only – to trusted journalists. Any such contacts with journalists should be reported to the London Communications department through the CD. 11.1.3 Public Action: Must be approved by the CD, who will coordinate with headquarters. Official letters to government officials Media releases and press statements (the London Communications department will draft these) Issue of reports on a situation or crisis Suspending or closing down of a field site or country operation 10 This section provided courtesy of MSF-Holland. 21 11.2 The following generic guidelines can help formulate a plan of action. (See also sections 12.1 on “Criteria for Undertaking Advocacy” and 13.0 on “Designing an Advocacy Strategy at Headquarters” for further discussion of these issues.) 11.2.1 Identify the Problem and Propose the Desired Changes 1. Clearly identify the problem: pinpoint the practices or policies that Merlin seeks to change. 2. Prepare convincing arguments on why this is a problem – your target audience will not see it as such, and will likely defend his current practices. Bring all arguments back to improving the beneficiaries’ safety and well-being: they are the reason we engage in advocacy. 3. Propose specific changes. How does Merlin seek to ameliorate or solve the problem? 4. Build arguments for proposed changes – again, focus on the beneficiaries and universal principles of humanity and international law. That being said, do not hesitate to mention the benefits that might accrue to the community at large from proposed changes (for example, opening up access to a closed area will enable Merlin to help reduce the incidence of infectious diseases, which can effect everyone in the village, including the local commander and his family.) 11.2.2 Make Yourself Heard 1. Locate the key decision maker and address your efforts to him/her. 2. Seek advice from influential local leaders on how to influence this decision-maker 3. Invite this person, as well as key community leaders, to visit your operations and familiarize themselves with Merlin’s work. Educate them as to Merlin’s humanitarian goals and independent, impartial status. 4. Create a contingency plan if efforts to reach this person fail or Merlin’s proposed changes are rejected. 11.2.3 Follow Through 1. Suggest a drafting committee be established with Merlin’s participation to bring about proposed changes 2. Follow through all procedural levels until the policy change is implemented at all levels. Keep a logged record of changes that do and do not occur. 3. Thank everyone who had a part in bringing about the changes, and keep them informed of any progress or setbacks to the process. It’s likely you will need their help again. 12.0 Advocacy at Merlin Headquarters Merlin’s advocacy is driven from the field, not from London. In most cases, fieldlevel advocacy initiatives will be best handled through direct, private or semi-public engagement with the parties involved. 22 Certain situations, however, call for the London office to act in concert with the field on advocacy. These situations might involve a particularly sensitive, politicized issue affecting Merlin’s credibility as an organization, or an emergency in which acute, widespread human rights violations are witnessed by Merlin field staff and demand a coordinated response with the London office. The task of the London office is to build on the information and advocacy measures initiated in the field. Examples of joint field-HO office advocacy include (but are not limited to): direct approaches to the donor; sharing and coordinating information on a given issue with other international NGOs for a collective initiative, private discussions or correspondence with relevant MPs; or a statement for public and/or press distribution written by the London Communications department. The CD is the field contact for all advocacy work with London. The first point of contact in London is the Operations desk officer, who will serve as the conduit of information should other London staff (Operations Director, Head of Communications, President) become involved. 12.1 Criteria for Undertaking Advocacy – London Office The London office will take up advocacy depending on a number of criteria, including those discussed above that are pertinent for field staff. (See section 5.2 above on “Criteria for Deciding”). In addition to these factors, other considerations include: Credibility -- Does Merlin have the experience and knowledge to address the issue credibly? Conversely, if Merlin does not advocate on this issue, will it harm its credibility? Clear objective – Has a clear objective been identified before advocacy is undertaken? How will progress toward that objective be monitored? How will Merlin know if its efforts are having a result? Probability of Change – How likely is it that Merlin’s advocacy will have the desired result? Resources – How much effort (ie, staff time and money) does Merlin want to expend? Who in the London office will work on this issue? Opportunity Cost – Would advocacy work come at the expense of other tasks that are necessary to Merlin’s operations? What is the opportunity cost in terms of other activities not pursued? Profile and Relationships – Does Merlin have the contacts and/or a reputation in this area that could be put to use for advocacy purposes? Links with other Merlin issues – Is this issue related to other concerns Merlin addresses, or is it a one-off? Links between Merlin field programmes – Is this issue common to more than one field site or country? Is it a regional issue that can be addressed by London with several field offices at once for greater impact? 13.0 Designing an Advocacy Strategy at Headquarters An advocacy strategy involving the London HO should be built around concrete objectives that complement and bolster what is being done at the field level. In designing a strategy, make sure the following questions are addressed: 23 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. What changes does Merlin seek through its advocacy? Who can make those changes (who is the target audience?) Who can influence our target audience? What means do we have of influencing them? What is our message? What is the medium most effective for getting out this message? What resources are required? As an advocacy strategy gets underway, the London office must make sure to communicate any progress or significant setbacks with the field through the CD. Merlin’s field staff are the ones closest to, and potentially affected by, any advocacy measures. Their involvement and support is absolutely vital. Hypothetical Example Issue: Threats to the independence of Merlin field programmes due to western military encroachment on its operations. 1. What changes does Merlin seek through its advocacy: To halt the US and UK military from wearing civilians clothes while performing “hearts and minds” goodwill gestures in the local community – a practice that makes soldiers and humanitarian workers appear equal in the eyes of the local population, and thus turns humanitarians into potential targets. 2. Who can make those changes? Political and military leaders. Merlin to focus only on the UK leadership. At the field level: military commanders working in the same areas as Merlin. 3. Who can influence our target audience? MPs, the media, possibly major institutional donors (DFID). At the field level: a coalition of NGOs active in the region. 4. What means do we have of influencing them? Raising the issue publicly and among MPs (London office). Direct correspondence and/or discussions with political leaders (field and London office). Targeted Merlin publicity on the issue (London office). Joint publicity with other NGOs (field and London office). 5. What is our message? Humanitarian aid workers are not soldiers, and vice versa. Confusing these roles jeopardizes our independence and puts our staff at risk. 6. What is the medium best suited for putting out this message? Merlin’s website, print correspondence and conversations with MPs, press releases to newspapers and radio (offer interviews with appropriate Merlin staff); joint publicity statements with other NGOs. 7. What resources are required: Staff time from Communications and Operations departments, money for any publicity materials. 14.0 Conclusion. Advocacy and Assistance: Two Parts of a Unified Whole Advocacy is an integral part of Merlin’s humanitarian mission. As humanitarians, we offer compassion and impartial assistance, not false hopes or utopian promises, to our beneficiaries. Today’s humanitarian crises result from a breakdown in political will and imagination. At Merlin, our task is to ameliorate the suffering that results from these political breakdowns. We accept that we do not have either the power or the mandate to stop the conflicts that in the end make necessary our humanitarian work. 24 The task of finding a solution to these conflicts is the responsibility of political actors on the local, national and international level. Humanitarianism cannot serve as a fig leaf for political inaction, nor is it a substitute for direct political engagement. What humanitarians can do is combat the complicity of silence that enables widespread abuses to continue, and point a finger at those responsible for finding a solution. At Merlin, we are driven by a moral imperative to speak out about the abuses we witness. Through advocacy, we will continue to challenge the pervasive indifference, cynicism and moral nihilism that characterise western societies. Through advocacy, we will also call upon political authorities to uphold their obligations to protect and provide for civilian populations as mandated by international law. Assistance and advocacy are part of one, unified humanitarian imperative: to alleviate the suffering of civilians, irrespective of nationality, religion, gender or ethnicity. In in so doing, we affirm our commitment to the principle of humanity that underlies our work in every corner of the globe. Appendices 1.0 Additional Resources International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC): “What is international humanitarian law?” http://www.icrc.org/Web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/iwpList104/707D6551B17F0910C1256 B66005B30B3 Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the Humanitarian Practice Network (HPN). See www.odihpn.org for a list of resources on humanitarian issues. BOND – A coalition of UK-based NGOs. Website contains extensive materials on how to carry out an advocacy campaign. Also offers training courses on advocacy. www.bond.org.uk/advocacy Crimes of War – edited by Roy Gutman and David Rieff. Easy to read primer on international humanitarian law. Organized alphabetically for quick reference. 2.0 Reference Documents 2.1 International Human Rights Law Universal Declaration of Human Rights International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees Convention Against Torture & Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Convention on the Rights of the Child Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners ILO Convention Concerning Indigenous & Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries 25 2.2. International Humanitarian Law The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and two additional protocols of 1977 Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field (Convention I of 12 August 1949) Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea (Convention 11 of 12 August 1949) Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War (Convention III of 12 August 1949 Protection of civilian persons and populations in time of war and Additional Protocol I, Part IV Geneva Convention relative to the protection of civilian persons in time of war (Convention IV of 12 August 1949) Protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts 1977 (Article 3 common to the four Conventions and additional Protocol II) 2.3 Principles of Conduct for The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Response Programmes. Go to www.icrc.org to access documents 2.4 Sphere Humanitarian Charter http://www.sphereproject.org/handbook/hc.htm 3.0 Sample Witness Statement Form (provided courtesy of MSF-Holland) – an form field staff can use to ensure that information is standardized and verifiable. WITNESS STATEMENT FORM 1 Documentation information Reference number: Interviewer: Location of project: Type date/location of incident: Type of account: first or second-hand information: Type of interview (in private, hospital etc.): 2 Witness information Witness code: 26 Address/contact person: Family status: Position: Name of victim (if different from witness): Address/family status/position: Affiliation, if appropriate: 3 Details of alleged incident Date and time: Description of alleged incident/violation: What happened? Description of incident/violation including: Number of victims Location (map or plan) Location of (mass) graves Where wounded persons were treated Other witnesses Who did it (alleged perpetrator(s))? If military: Description of uniform unit command person in charge name and rank perpetrator ethnic affiliation perpetrator known to victim type of weapons used... If not military: perpetrator(s) known to victim/family/witness name/organisation number persons involved in attack under influence alcohol/drugs type of weapons used. Motivation Was anything said during the attack? Where was the attack from? What was the target? 27 Alleged action by responsible authorities (military, police, local officials, etc.) Signed and dated by the interviewer 28