Minersville School District v

advertisement

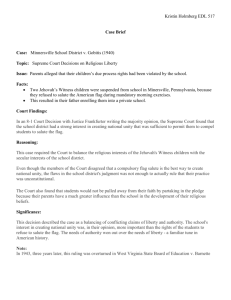

Minersville School District v. Gobitis NARRATOR: President Roosevelt ignored the calls for Justice Black's resignation, and Black stood his ground. He wasn't going anywhere. But the question remained: would Justice Hugo Black be willing to protect the rights of all? There would be no quick answer because in the 1940s, outside of economic liberties, the Court had almost no history on protection of individual rights. It started with children who were kicked out of school -- because in the run-up to war, the schools were at work building patriotism. In Minersville, Pennsylvania, all kids had to salute the flag. BISKUPIC: There were two little kids there, Lillian Gobitis and William Gobitis. Lillian was 12, William was 10. They were Jehovah's Witnesses, and it was against their religious faith to pay homage in any way to the flag. The Minersville School District said no exceptions, and these children were expelled. SIMON: So their parents brought suit on the basis of their religious freedom. And they won at the lower courts. And then it came up to the Supreme Court of the United States. NARRATOR: It was a brand new Supreme Court, remade by five fresh Roosevelt appointees. Black was the first. But the ornament and leading light was to be Felix Frankfurter. He might have been the most famous lawyer in the country, a towering figure in Roosevelt's brain trust. He was an immigrant, an Austrian boy who landed on Ellis Island at age 12 -- without a word of English. But he'd dazzled everybody who saw him since, from the Lower East Side to Harvard Law School and beyond. SIMON: Everybody assumed that Frankfurter would become the leader of the liberal wing of the Court. He was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union. He was an early supporter of the NAACP. He defended Sacco and Vanzetti, the two immigrant anarchists. He advised Wilson. He advised Franklin Roosevelt when he was Governor of New York. And of course he became a almost one-man employment agency for the New Deal. They were called Frankfurter's hotdogs. NARRATOR: Some jurists come to this Court hat in hand. Frankfurter swaggered in. He expected to sweep the court along ... and he did. He wrote the flag salute opinion for an 8-to-1 majority -- and dismissed the plea of the Gobitis children with magisterial certainty. BISKUPIC: What he says is that maybe the policy isn't one that he would agree with, but the states, legislatures, school districts, have the right to enact it. SIMON: It's a theme he struck again and again on the Court, and that is, it was really the theme of judicial restraint. As long as the legislative and executive branches acted reasonably, the Court ought to find their actions constitutional. NARRATOR: In this case, as in most others, Frankfurter thought democracy should run its course. If the majority elected a school board, and the school board wanted a flag salute, then everybody must salute. GILLMAN: It's not that he didn't recognize the value of individual liberty, but he thought that fundamentally, the freedom of the people had to be protected through democratic institutions and not through court-imposed settlements. It's an ethic that is extremely deferential to democratic outcomes, but it turns out that the democracy isn't always as protective of people's rights and liberties as we would like to think. NARRATOR: Real people had to pay the price for the Court's deference. In this case, Jehovah's Witnesses paid dearly. The Gobitis kids had to be sent away when the family was threatened by vigilantes. BISKUPIC: When this ruling comes down in 1940, Jehovah's Witnesses are being, you know, pulled out of their homes, pulled from their cars, literally tarred and feathered, pushed to do humiliating things like kiss the flag, forced to drink castor oil, and paraded tied up through the streets of these small towns. There was one incident of somebody being kidnapped and castrated. And newspapers across the country were outraged by what happened.