WS 164 The evolving Internet ecosystem: A two

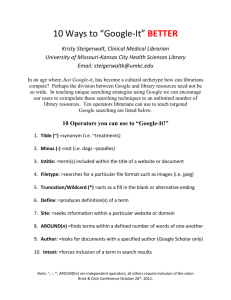

advertisement

WS 164 The evolving Internet ecosystem: A two-sided market? >>Scott Markus: Good. Okay. Well, I think we can get going. People are are obviously still drifting in from coffee but I think they are just going to have to drift in. I'm Scott Markus. I work for the German institute, the V I C. I will be chairing the panel. My good friend Patrick Ryan from Google will be joining us. A L I Hussein who works with the three mice interactive media in my reeb owe, Taylor Reynolds from the OECD and Dr. Robert pepper from Cisco systems. So I thought it would be useful in this case to say a few words at the outset about what two-sided markets are, and about how they have sometimes been used to analyse electronic communications markets, because I realise not everyone here are economists probably not everyone is really so familiar with the term. I know particularly the engineers may not have heard as much about them, so I think it might be useful to have a quick framing remarks. Basically two-sided markets are a relatively new branch of economics. They deal with markets that are two-sided, or sometimes multi-sided, where a platform brings together the two sides of the market. They have often been used to -- free to air broadcast television, another example that's sometimes given are singles bars when it is helpful to get the right number of men and women together in one place but a noteworthy characteristic is in a two-sided market what is especially important is to get the right levels of participation and of usage, and so bringing together the two sides of the market is crucial, and sometimes that can lead to behaviours that would be irrational in a traditional single-sided market. There is an acktradition on this that goes back a bit of a way. The real break through paper next year my view is a well-known paper by a group in France, a paper by R O CH ER and Jane T I R O L. It was published in 2004, there are many subsequent publications. In broadcast television, free to air television, usually it is the programmers, the senders who are paying, and the end user the consumer, the viewer, usually pays little or nothing. Now again, to an economist, we look at this from a classic, single-sided market view, we say, "How could the price be less than the March nal cost?" It makes no sense but in a two-sided market it does make sense. Everybody benefits. So again, driving participation is key. Now, communication markets are, in some sense, always two-sided. This was really one of the very useful observations -- oh. Thank you. Sorry. So, every market is a two-sided market. But a two-sided market won't always yield a different analysis than a traditional analysis. Again, what the literature gives us is some rules as to when it is likely to make a difference. Now, a couple of cases where two-sided markets have been used for analysis have been in voice call termination payments, and more recently in a fairly hot debate about arrangements between network content providers and network operators. Funding next generation access deployment is another area where two-sided markets have been suggested as a mechanism to do it. On the termination side, again, it does have elements of a classic two-sided market. You've got, in the typical system, the so-called calling party pays retail system, you've payments going only to the originating network, not to the the network that completes the call, but there is a wholesale payment, an adjustment between the two networks. The two networks collectively form the two-sided platform here. So it has been analyzed on that basis with results that I would say are a little less than fully satisfying. It turns out that the prediction from a two-sided market value would be if wholesale prices go down, as they have, you would think that retail prices should go up. If that were the case, these data would show the wholesale and retail payments based on some third party data from Merrill Lynch, ought to move in opposite directions whereas in fact they move in the same direction. So in these two-sided markets a lot of different things can be happening at the same time. The results can be difficult to predict. A little closer to home, the suggestion has been that content providers or search engines or what have you, should be making payments to network operators important to remember, again, is that the platform here is probably not a single Internet provider, but rather the Internet providers altogether collectively. Typically, a content provider, a video provider, has its own Internet service provider he that may be different from the one that serves the consumer and the interests are not necessarily aligned. This argument was probably best made by a 2010 study by a consulting firm A T K that argued that those who benefitted traffic were those who produce it more so than those who consume it and that those who have to build and operate the networks don't necessarily benefit from this because the consumers are locked in at flat rate prices. Now, the argument here also was about exploding traffic and therefore rapidly agreeing costs. So the natural question is; do we've rapid growth in traffic? Do we've rapid growth in costs? These are empirical questions. This is a picture from the well-known children's book Alice in wonder land, and those of you who know the books will remember that Alice seemed to always be eating something that made her grow or shrink, and we all know that uncontrolled growth can cause problems. So that being the case, what do we have in the Internet? Well, these are data from Cisco systems, it is based on data from Cisco systems, they do a wellknown stud efficient likely Internet traffic growth over the coming years, and what we see here is growth, the upper graph represents the fixed network, the lower graph represents the mobile network. They are not on the same scale, so the mobile is still a small fraction of the total, but the percentage growth year over year in mobile is much better than in the fixed network. In fact, in the fixed network, based on the same Cisco data, the growth is tremendous year over year, but in percentage terms it actually declines year over year, so for me as someone who has been in the industry for many years, I would have thought that the problems might have been greater ten, fifteen years ago when traffic growth rates were 100% per year, but of course, on a very different base, a very different base. Cost trends also are more complex than one might think. Volumes go up, that's the blue lines here, go up over the years, but unit kses tend to go down for Moore's law kind of reasons. These relate to service provider routers and long haul opto electronic equipment, so you've opposite trends with effects that are different and that partly cancel. So, some of the questions I wanted to Kew up for today is does a two-sided market analysis tell us anything useful here? Does it tell us something different from what we would get from a conventional analysis? Really on which side of a content market would you expect price signals to be stronger and why, which kind of costs are really dependent on traffic volumes and which depend more on the volumes of users and probably most important, and this is a question that also links very much to the critical resources discussion that many of us saw yesterday, you know, what would the likely effect be of a two-sided market change in the structure of payments? You know, where would those payments end up? Who would benefit? Who would be hurt? Would there be net gains or net losses? Those were the questions that I wanted to turn over to the panel. So, with that said, why don't we proceed next to Dr. Patrick Ryan of Google, and I will give you a few minutes for each of the panelists to make their opening structuring statements. Patrick, you can start. >>Patrick Ryan: Great. Thank you Scott. It is a pleasure to be here. I'm happy to be here because as Google we obviously are one of the principal parties in this discussion in using this infrastructure. There are a lot of claims about over the top companies using the infrastructure of other companies, the tell could hes that, you know, that provide service to the end users and this of course generated all this concern. It started back in 2005 when Ed Whittaker, the CEO of AT&T said I'm not going to let Google use my pipes for free. Now interestingly AT&T has completely backed away from that position has have many other world tel co-s and there is really a split among telecommunication companies in this review. So we're looking at a debate around business models but also to some extent and I think this is an important point that's under-emphasised, about net freedom. These are commercial arrangements at stake. Sigh Ronically, companies like Google and Facebook and Amazon, big players on the Internet, can afford, theoretically, to make contributions in addition to the many billions of doll are as that are paid in transit fees in order to be access Internet already, and in addition to the infrastructure capital contributions that are made on an annual basis, for example Google invested US$3.5 billion in infrastructure in transit investment last year in 2011. It is a non-trivial investment but what of the smaller users? What about the companies that are developing in the garage today, the next Google that may come from a garage in Nairobi? Where do you draw the line? at what point do you say that the large company should-ing paying but the small company should not until they reach a certain point of success? It becomes a very tricky thing and potentially if this were put into place, would, in fact, lock in the Internet and create a situation where the large providers like Google and Facebook and Amazon and, you know, the companies that everybody knows today, would, in many ways, lock in their position, you know, where they are and that would significantly affect the ability for new entrants to come in and to be able to speak their minds. So I just would like to suggest, and I would like to hear some comments from others today that, in addition to the commercial issue, an issue of net freedom. If we start putting tools on the Internet not just for large companies but for other speakers in the Internet space, this could really significantly affect the way the Internet is used in the future. >>: Next, Ali Hussein from three mice interactive. Nairobi. >>: This is an interesting discussion, and I would like to really talk about it from an African perspective specifically Kenya. To a large extent, I would like to concur with the sentiments that Patrick has talked about here, but, you know, I think the biggest issue here is a lot of the TelCos really do have a point. I think sometimes, I think from a Kenyan perspective especially, the TelCos who are talking about this kind of are a bit scits owe fren I can in terms of how they engage in this area so on one point right now we've got a huge debate about mobile termination rights. You've got Safari Comm fighting with the other smaller TelCos because they have the network effect, but on the other hand they are fighting a stealt war to try and influence the Kenyan position on ITRs, which are going to be happening in Dubai. I would like to give an interesting example of a small start up in the gaming industry in Kenya. It is a company called (Inaudible) that's based on the taxi operators in Kenya. This game has become very interestingly. It has become phenomenally successful. Over the last six months it has been downloaded in about 200 countries as far as Mongolia. People are downloading it and playing it. Now, asking a small start-up like that to start kind of paying a toll for usage I think is going to be, you know, a serious issue that we've from a regulatory and competitive perspective. It is something that we must face. As you look at the TelCos, yes, they have an issue because there is huge investment that, you know, is actually being put, so our question in Kenya, we're asking a lot of the TelCos is; can you come together? Is this a case for a multi-stakeholder engagement? Probably with government? Because we may not have the same kind of -- we may not have the same kind of deep pockets that American and European TelCos have, so I think, really, that's my statement on this issue. >>Ali Hussein: Thank you very much Ali Hussein. Okay. Next Taylor Reynolds from the OECD. I know that you looked at all of these issues. You looked at Internet interconnection and particularly some of the developing country issues with IXPs in that context. You also looked at the MTR issues, so we very much welcome your thoughts here. >> Taylor Reynolds: Thank you very much. My name is Taylor Reynolds and I'm an economist focusing on the information economy at the OECD. We've done quite a bit of work on two-sided markets and we've three specific requirements for something to be considered a two-sided market at the OECD. The first is that you've two distinct set of customers who need each other and they are serviced by a platform in the middle. One of the other things that's important for us to keep in mind is that there are extras, so things that happen this one group where grg to affect people in the other group. These call these extra nallities in economics. I think finally one of the things that's most important, the price structure that's set by the platform is non-neutral. That means that changes to the platform, the way that pricing is done, is going to affect the level of transactions across between the two different groups so these two-sided markets quite common in telecommunications and one of the things that we've seen recently is that you've to be careful with the way that you regulate these types of markets because you need to take into account both sides of the equation. You need to look at all the groups that are affected by the platform, and you cannot just make rules that affect one side without it having repercussions on the other. One that I would point out is exactly what Ali has brought up here about mobile termination rates, and termination rates in general, because we've seen some countries in the world that are interested in raigz the price of termination, particularly mobile termination as a way to raise revenue in their countries, but because you are in a two-sided market here, what this means is it is going to have repercussions on the other group and across the whole economy. So for example we've seen recently that ga in a has increased the price, termination rates, when you call into the country, and we've seen a drastic decline in the number of telephone calls that are coming into the country.. The Internet is becoming a fundamental infrastructure for the economy. If we start playing around with these without considering the full ramifications of these decisions we can end up actually hurting the economy for a little short run gain. That's I have to say for now. >>Scott Markus: Thank you very much Taylor. Next Dr. Robert pepper of Cisco. I'm sure that you will have some thoughts about the data and I know that you've thought a lot about these issues. >>Robert Pepper : Thos Scott and thanks for the organisers of the session. So let me go back to Scott's discussion or presentation about two-sided markets and try to make it very concrete and practical. I'm going to talk about three, actually four very concrete examples of two-sided markets and communications and you will recognise them, and they are actually very proconsumer, pro-competitive, and create value across the entire value chain. The first one is the Amazon Kindle in the US. So those of you who are not in the US may not be as familiar with but of course Amazon has its e-book reader, and you buy books, and they are downloaded to the Kindle so you can read them. Most people, the average consumer, has their Kindle and they buy a book, whatever the price is that Amazon decideds, Amazon determines the price of the book with the publisher, and it magically shows up on the Kindle. People don't think about how it gets there. How it gets there is Amazon has a commercially-negotiated relationship in the US with AT&T to use AT&T's mobile network. So it is using their 3G network, you buy the book, the book shows up. The consumer has no idea how it gets there. They don't care. Right? They don't pay AT&T something extra to deliver the book. They just buy the book. The relationship on delivering the book is between Amazon and AT&T. It is a great example of a two-sided market that the network operator, AT&T loves. They get paid for the transmission, Amazon loves it because they get to sell a book and it shows up and you love it because the book shows up. You bought the book. It is a commercially-negotiated, economic relationship that outside of any regulation, because the prices in the US for mobile services is not regulated. A second example of two-sided market that everybody is familiar with is toll-free calling, right? So you want to call your airline and there is a number for you to call, so you can make a reservation, you can call this from anywhere, you don't pay for the call. The airline pays the network operator for the call. People love it because they can call to make their reservation or any toll free, I'm just using a reservation for an airline or it can be shop did go, it did be any toll free, but the business with whom you are transacting business with, whether it is an airline, or a store, or if you are calling, you know, Cisco for Customer Support, we pay our network service provider for the call, the customer does not, but the customer benefits. Again, great example, two-sided market, everybody is happy. There is huge value across the value chain. A third example was an experiment that bell south ran in the United States in the early days of the broadband before it was merged into S T C which then became AT&T. In those days wrote band, you know, your basic broadband package in bell south territory was 768 down and 256 up but when you went to the home page there was something called turbo zone, and you could buy a movie, it was a streaming movie that you could watch. Now we sort of take these for granted with video condemn and, but with a 768 down 256 up, your broadband connection couldn't support the streaming movie, so what they did was when I bought the movie for US$5 or US$6 whatever it was, and they were experimenting with different price points, the movie distributor, the studio, paid bell south to increase my downstream bandwidth to probably 3 meg per second for the duration of the movie so that I could watch the movie and then at the end of the movie I went back to the package that I paid for on my broadband. Again, across the entire value chain, the consumer loved it, there is a movie they wanted to watch, the studio loved it because they paid to boost the quality of service of the network for the duration of the movies, they get paid for the movie, bell south liked it because it was an additional revenue stream. Commercially negotiated. These are all examples of where the network operators could benefit the content providers, or the businesses benefit and the consumer benefits, so these are the types of arrangements that I think of as very concrete in this space. Then there is fourth example which is the -- and this to some of the points I think Scott laid out in the more theoretical discussion of the two-sided markets -- and that's this notion of, "Cost causation". I mean, typically, in the traditional telecom world, and it is almost a silly concept but it is one that has withstood time, if I make a call, I'm causing the cost on, you know, for the network. I pay for that. Well, in the Internet world, if I'm a student in (Inaudible) and I want to take a course from Stamford university which makes a lot of its courses available online for free, they click, they go to the Stamford university website, they click on it and they want to watch the -- they get the course, which is essentially a downloaded or a streaming video. Now, the question is, is the cost causation the Stamford university sending the course, or is it the student who is requested the course? That's why this concept almost is not really relevant because it is again there are multiple parties that benefit. What we have to be careful of is that we do not end up having unintended consequences of having arrangements that are not commerciallynegotiated, and mutually beneficial across the value chain that could result in that student not having access to the courses they want. On the other hand, there is not a commercial negotiation or a commercial relationship that has been worked out between Stamford and the networks. Last point I want to make goes to this question of calling party pays, and one of the things that we've learned in the mobile world, right, when Scott and I were at the FCC and we were developing the rules for mobile operators and how they interconnect with one anothernd a how they connect into the local network, the industry, not the regulator, the industry initially developed an economic model that was not calling party pays, it was essentially a bill and keep regime where the wireless operator paid for air time. Initially, there were people criticising that model in the US saying, "Oh, you know, they are not going to use their cell phones, they are going to -- people turn them off because they have to pay when somebody calls them", well it turns out empirically that turned out not to be correct, and in fact, the bill and keep regime in the US for mobile led to the creation of a different business model, and that business model was a business model with very large buckets of minutes where there is predictability on what my cost is, and in fact, at the margin, for every minute I talk on my mobile, it is free as long as I'm within my basket of minutes, and as a result, mobile users in the US for many years actually had at least two and in some cases three times the average minutes of use of mobile customers in Europe, Asia, anywhere else. Precisely because there was a predictability of what their bill will be at the end of the month, and that drove a huge value. It also overcame both the economic theoretical and practical problem, which, by the way, we actually looked at and tried to resolve at the FCC, and that's the problem of termination monopoly. And the problem there, which is again, an important economic question and nobody has been able to solve it. I can have six operators competing -- ten operators competing for my business on the originating end. I get to choose my operator based upon the package, the service, the price, the quality of service, a whole range of issues, or of variables once I select my operator, when Taylor calls me, right, in a calling party pays regime, his network has to pay my network and there is no competition on termination. Therefore, that is one of the unintended consequences of that is that because of the termination monopoly problem we see very heavy-handed regulation in countries regulating mobile pricing, and these wholesale relationships in countries that do not have a bill and keep regime. In a bill and keep regime, right, my mobile operator, you know, all of these companies competing for my business, they keep the money, right? But because there is no incremental cost to terminate because I'm paying for the termination, there is no monopoly on termination and therefore pricing is not regulated. What it also did that was very effective in the US was it allowed the operators to internalise roaming to the network. So my local calling area in the United States in the entire country, because it doesn't cost my mobile operator anything more to terminate a call whether it is locally or across the country. So, we looked at this as a theoretical economic problem that has very large, economic consequences for the industry and levels of regulation, and I think what we're moving towards, what I would hope we're moving towards, across, you know, as we migrate the entire industry ecosystem, is moving away from regulation to much more commercially-negotiated arrangements that were not going to have to have regulators regulating either, you know, the wholesale or the retail prices because we'll have sufficient competition and the right market structure and incentives that will take care of that, but we do have to worry about ensuring that there is value across the entire value chain, and that all of the players in that value chain actually have the ability to receive revenue from the different pieces, but it should be commerciallynegotiated. Thank you. >>: Thank you Robert for a very, very clear and insies I have intervention. You've raised cost causation as an issue. Cisco obviously does a lot of analysis of trends and I know one of the more striking trends in the V and I in recent years has been the huge ramp-up of video traffic. When we look at cost causation clearly is question is; what fraction is initiated from the sending site, so to speak, say, for example, if there is a huge Microsoft fix, one might argue that that's launched from micro soft and the customer has limited ability to intervene. You might argue that the other way too. Do you have a sense of how much is initiated by the end user? >>Robert Pepper: Sure. First of all, when I get a patch, not just -- from anybody, I get my updates, those are relatively small amounts of data. I mean, relatively speaking. Where we're forecasting -- and by the way, with our forecast it is a rolling five-year forecast, we've done this for six years so we've actually gone back at the initial, the early years of the forecast and we checked what actually happened, so we've been able to do that for two years now, and we're within 10% but we tend to be on the conservative side, so the data, it turns out, are highly reliable. We're very confident in the reliability of the data. What we're forecasting for both fixed and mobile of traffic is between 67 and 70% of the traffic is video. Now, video does not just mean movies. Video, in multiple configurations, it can be short form video, you know, You Tube video, it can be video to my flat panel television at home, it can be Facetime on my iPhone to your iPhone so it can be two-way video. That has different characteristic requirements, right? That requires low lateiency and symmetry whereas if I'm downloading video it is different than if I'm streaming video, so there are differences in the types of video which also have implications for notions of quality of service. Quality of service is not just higher speed, quality of service includes down load, up load, latency jitter, I like to talk about networks fit for purpose, and where the technology is having adaptive networks, so the networks know the type of application that's coming across the network so that the network characteristics, if I'm doing email, latency is not important. If I'm doing voice over IP it is really important. You have to have the ability, and what we're doing now have the device be able to talk to the application server. That's important because if I'm watching a movie on my iPhone, I only need maybe 100K in terms of pixels, right, but if I'm watching it on my big flat screen TV I want at least a million pixels. I want a mega pixel. So if they are sending it for -- if it is one size fits all, if it is only being sent for my big flat panel TV and I'm watching it on this I have to throw away 95% of the bits. On the other hand if it is being sent for this it is going to look terrible on that. So there needs to be this adaptive nature as well, and this is, again, the kind of thing where I think there are opportunities for commercial arrangements between network operators, content providers, that are mutually beneficial to be able to provide these new kinds of services and new business models, completely outside of regulation. Taylor? >>Taylor Reynolds: Yes I'm not a very popular person at home right now because I live in France and my ISP currently is -- at heads with Google about the delivery of You Tube traffic. So my ISP is asking for Google to spend money to upgrade the connection internally in their network so they can deliver video, my I SP says no, Google says well, it is not our business if you cannot deliver the content, and so what happens is You Tube videos in my house will load about 40%, and then they will stop, and you wait and you wait and it will buffer and it will go a little more and then it will stop and my kids, my ten year old daughter, is going ballistic because she cannot watch these little videos that she likes, so we're considering switching I SPs, so I'm in the process right now of probably switching I SPs next week so that we can go to a provider that has this arrangement worked out. Now, the reason I think this is important is because in France there is a competitive telecommunications market where I can actually switch providers and not pay a lot more money, and I can actually get it done right away. So I might have to wait a week or two for the actual transition to take place, but I can switch providers without some huge cost, and what that allows me to do is vote with my feet. I can say, "I'm not happy that you didn't come to a commercial agreement between the two parties, and therefore I'm going somewhere else", and I think that's the sign of a healthy market, and that will help keep things in check, and it is one of the reasons that telecommunication regulation, making sure that markets are competitive, is extremely important so that we can let these two markets, these two-side markets operate efficiently., Ali Hussein? >>Ali Hussein: Yes I also want to add on to that from the perspective of the Kenyan market. We're also seeing some very, very, very top competitiveness which is raising the issue, because you've got service providers who are now going to the regulator for protection. It is beyond the empty hours that we've talked about. You are finding that new I SPs are coming into the market who are offering ten times the bandwidth at a fraction of the price of the current service provider who I have, so, you know, much as the market is very fluid, but is there a question for a balance between regulation and market forces? Because I can tell you that a lot of the TelCos and I SPs in Nairobi are bleeding red Inc. >>: So I think we've a lot of thoughts here about win/win solutions. I tell you I'm going to take the Liberty of switching a little early, I know I have got one person who is enthusiastically asking to pose a question from the audience, so can I take the Liberty of -- I will take the Liberty of doing that. Let me take one more comment from a panelist then then we'll switch back to you. On this question of Kenya, I'm interested in understanding a bit about the distribution of payments within among the network operators. I think Kenya is one of the not so many places in Africa that has, for example, an IX P, an Internet exchange point. After this I will be interested in hearing from Taylor about how this works in many other countries as well, but first, Ali Hussein, how do payments work and how well do they work among the network operators in Kenya? >>: Payments? >>: Is it transit arrangements? Can smaller I SPs get peering in ->>Ali Hussein: Yeah. Okay. So in Kenya we've an organisation called the telecommunication service providers of Kenya who have put an Internet exchange point, and the Kenya IXP now has grown to become a regional one, so we're serving, to some extent, Tanzania, Uganda, and next online is Rwanda and bar iewndy that will be all within the same IXP infrastructure, so for local traffic basically there are certain termination agreements within the organisation, because most, I mean the majority of the players, you cannot have access into the IXP without being a member of TESBOC. >>: Thank you. Taylor, I was actually going to look a little to you for how arrangements and some of the other countries in the region more generally, in developed and developing countries, the OECD recently published a study about exchange points, the Weller Woodcock study and it has been a concern that smaller I SPs were not able to obtain connection, they had to effectively trom bone their traffic outside so sorry Taylor for that long introduction but away you go. >>Taylor Reynolds: Yes. This is actually quite a big problem in many countries in Africa, where if you were an Internet user in-(Inaudible) your Internet traffic, that email travels from M all the way up to France and then comes back down so we call this trom boning and it is extremely inefficient because traffic internally within the country can be very cheap but as soon as you start using international transit routes to route all of your domestic traffic between operators is going through France it becomes a very expensive proposition. That trickles down to higher costs for subscribing to the Internet as a user and what do higher costs mean? Fewer people connected to the Internet, and then the next logical step is the fewer people who have connections to the Internet, the less that the Internet is a core part of the economy so these are areas that we think are extremely important to address and one way to do this is a very cheap operation which is developing an IXP, an Internet exchange point. These things honestly do not cost, they are not very expensive to set up, they can be between US$50,000 and US$200,000 where you've traffic exchanged between operators locally. One of the big challenges, though, with Internet exchange points is that it is not just the equipment. You actually have to have training of people who know how to do this and you need to get all of the I SPs on word and show them why it is important to actually exchange traffic locally, but in the end we at the OECD think it is extremely important to get as much traffic transferred locally as possible. >>: Thank you. At this point why don't we take a question or two from the audience and then I might move back to the panel. Jeanette Hough man? Try turning it on. >>: Okay? I'm a researcher but I'm not an economist, I'm a political scientist, so I look at what you call two-sided markets as battle hes between various approaches to -- so I look at it as a battle. I have been wondering how new content distribution technologies or services, how they affect the two-sided market, and which side of the battle the ISPs or the content providers actually benefit or get weaker or stronger in this negotiation of pricing. >>: Could you describe what you mean by new content distribution models? Give an example? Yes. Could you give an example of what you mean by a new content distribution model, just to illustrate it? >>: What I mean is new technologies that bring the content closer to the end user and thereby effectively reducing the whole cost of data traffic. >>: Sure. I will take a stab at that. I think that one of the -- it is not really a new technology but it is certainly a new process, you know, what Taylor was talking about, and that's this idea of Internet exchange points, and the interesting thing for me about Internet exchange points is somebody that, you know, has spent 18 years in the the telecommunications industry, is that they are just really, you know, not very well understood, even by experts. Before I joined Google I had no understanding about Internet exchange points at all, and so, you know, this has been a learning process for me. I'm sure it is a learning process for regulators, but it is an absolutely key best practice for keeping that content local. For example, the Taylor -- the example that Taylor gave is great because it enables I SPs to exchange information within a particular region. It is also, I find, very interesting to sort of look at and study, and I think there is further academic research here that could be very valuable, the different kinds of business models for Internet exchange points alone, in the United States, many of the Internet exchange points are, for example, commercial in nature. You know, they have a business of running an Internet exchange point. It is for profit. They run it like a business, and facilitate the exchange between providers, but that's fairly unique to the United States. In other parts of the world, like in, you know, in Africa, and in Europe, the Internet exchange points operate on more of a co-operate I have model, where it is not a for profit venture but the members will contribute and all be part of it as a co-operate I have. So Internet exchange points is one key part. Another thing is the -- these content delivery networks. Right? And companies like Google and Facebook and Amazon and Microsoft have their own content delivery networks that they will bring closer to the user. A lot of times they will locate these in Internet exchange points or in other nodes that are closer to the user and there are other companies, there is even a third party, sort of a market that's developing for this, companies like limelight that are providing this service for others that, you know, maybe not be able to afford their own model. This is something that we, as a company, are just now becoming more comfortable with talking about publicly. We haven't given any sort of a press release on this at all, but if you look online at peering.Google.com you can now see a map of many of the various different points where we'll bring our content closer to users in various different parts of the world, and it also describes some of our companies' philosophy on peering relationships and on what sort of conditions we would like to see in order to be able to bring that an could tent closer to the user. >>: Scott, on the CD ends, Patrick makes a really good point. These CD ends or content delivery networks have really come to the the forein the last three years, and there are traditional telecom operators now also that are providing CDNs. There are Federations of CDNs that are evolving and developing, so again, these are all commercial responses to the huge demand that is being created, and again, they are called CDNs because they are content delivery networks and most of that content is video. So, you know, it is not just the Internet exchange points, in the US, you know, you had public exchange -- we call them exchange points then, right? Public exchange points, we had private, you know, peering exchange points, there are -- they call them interconnect hotels, right, some of them good flooded last week in lower Manhattan, but it is where all the big network operators connect, some of these are commercial negotiations commercially poured some of them going back to Scott's early days in the Internet with the east, west, the early interconnection points were -- some of them were literally in university broom closets where you had these networks connecting. Now, it has evolved way beyond that, but the important point about Internet exchange points is that one of the trends that we're seeing in order to bring retail prices down, bring down the prices of international band width to local operators, the local carriers is that you have to keep the traffic locally to the the greatest extent possible and it is not just trombone-ing on email but it is the -- especially in Africa, it is the traditional network configurations between east Africa, west Africa, if you were in Kenya and you want to send an E it went from London to Paris to Paris back down because these were the old Colonial telecom routes we now have much more bandwidth (inaudible) the fibre networks, the big issue now within the continent bringing broadband traffic from the coastal countries to the inland countries and this is this can only be done through Internet exchange points keeping the traffic locally, regional, but also it is important having the bilateral relationships and negotiations so that you can get of traffic from one country to the next and really bring down the costs of bandwidth to the local operators because the local prayeders are having to pay amounts, very high prices for international bandwidth, so that flows through to consumers. It is happening and by the way, the market is taking care of that, if you go back fifteen years, that was the complaint in Europe. You sent an email from Paris to London, and went through western Virginia, because the prices for interconnection and high bandwidth within Europe was too high. Right? That came down. We had the same issue in Asia. The market took care of it. We now have a competitive cable surrunder ing Africa, and again, it is being driven down, and what we need to do is more of these Internet exchange points and things like the CDN Federations. >>: Thank you Robert. Well, I think this would be a good time to open up for some audience questions. We've got about a half hour left so we've enough time to take a few. Good. There, please, could we get a microphone over there please? Please introduce yourself. >>: Hello. My name is Carlos courtes, I'm a researcher for the university. You hear me? Of pal air me in arnlg enknow that. -- Argentina. I have a basic question, coming back to what the gentleman was saying from Google, it is like the relationship between the two-sided market and the openness of the Internet because for people that are not working in the economy, it is not the point of the Internet, it seems sort of a risk in terms of where is the business driving us in terms of the Internet, so I really don't know whom to pose the question, perhaps to all of them, exactly what you think is the relationship between the two-sided market or the evolution of the business which you have explained and the open Internet and the capacity of people being able to disseminate any kind of content without being discriminated in the terms that we've been working in terms of expression approach. Thank you. >>: I'm hesitant to answer because I just love this topic and I brought it up, but if there is anybody else -- I do think that this discussion is, you know, it tends to -- people get lost when it becomes a commercial discussion, right? You mention two sides, you know, you are dealing with two parties at the table (inaudible) for the openness of the Internet in many different ways because it is not just the user that don't think about how the content gets to them, they just want the content there. It is a also the people that inowe vait. I love, one of my favourite things about working at Google is the collaboration I have with convince surf is and the thing that he always talks about is the platform that the Internet has created for permissionless innovation, and that really applies to small users, I love that example that you about the video game company in Kenya and suddenly somebody had this great idea and it just blew up, right? It was able to blow up, and able to grow, because they didn't have to ask for permission, whoever developed it, and then, you know, these products and services, or just ideas and thoughts could continue to disseminate without any restrictions, and so it is not a connection that an obvious one, but it is certainly the core of the Internet is the ability for, you know, anybody to put anything up on the Internet, have a commercial presence or not, and to be able to make that decision without having to think about the barriers to entry. >>: Thanks. Did anyone else want to jump in on that? >>: Maybe to just also add into that, I think we're also seeing an interesting evolution. Maybe it is kind of new from an African perspective, but I think this has been going on across the world. This whole concept of triple play, so you are finding now that TelCos are not only offering telephony and Internet connectivity, but they are now also offering content, TV content. So we have an interesting company in Kenya that started as an ISP, maybe about ten, fifteen years ago. It has evolved now, it is called (Inaudible) online. That stands for citizenship in Swahili. It has now moved to become the biggest triple play player in east Africa with a brand called Z UK U so you are actually finding even the competitiveness rather the markets are becoming more and more blood, broadcasters are becoming TelCos, TelCos are becoming broadcasters, they are becoming content providers. They are becoming financial services providers, I don't know whether you have heard the story of E which is a money transfer, or rather a mobile money transfer service. Kenya accounts for 70% of mobile payments worldwide. 70% of mobile payments. This is from a tell could he. When E was launched a few years ago there was no regulation, nobody had told a tell could he that they could start a money transfer system. Nobody told them that they couldn't start a money transfer system. At some point the banks tried to fight it through regulation again, so we're seeing, again, the issue about business models evolving to the extent where you are finding organisations running and hiding behind -- forgive me for saying this -- hiding behind the skirts of regulators for protection, instead of evolving around market forces, so I think from my opinion, from my humble opinion, this whole twosided market, you know, concept, has evolved from that to an extent now, we were discussing this just before the session started, it is now becoming a multi-sided, you know, situation. Thank you. >>: Why don't we take another question from the audience? >>: We're technology -- I don't know if you all know Luigi, I will introduce him briefly, he is the president of ET N O and he has been vocal and has a different view. I would love to hear from you on this panel if you are interested. >>: While the microphone is coming up, just one additional thing, responding to the last question, so there is some new business models, new technologies that actually are making it easier to entry but again there has been Commercial Development. So for new entrants for small start-ups, dismoi, even four or five years ago you needed a relatively large amount of capital to buy servers, to get the processing you need to write code, et cetera. Now with cloud services like Amazon's cloud services, you buy your processing, your computing, as you need it, and the cost of entry by new entrants has plumb id, right? It doesn't mean that their computing is free, they pay for it, but because of the shared nature of this across networks, the ability to enter the number of start-ups, the vibrant atmosphere now with small start-ups that start with almost nothing because you can do it from your bedroom or your kitch ep and you buy your computing as you need it. These are the kind of things that are happening in these new market relationships and the new technologies that actually are reducing the cost of entry by the new guys. >>: Thank you very much Robert for an interesting intervention. Okay. At this point, Luigi, Chairman of ET N O, we would be very interested in your views. >>: Thank you very much. Even if I'm here more to listen rather than to speak, and I think that this is a very important occasion, and I think is very interesting, such kind of opportunity that we're having in these days here, but I would like to make, to comment and then to have your reaction on what I'm going to say. First, on the issue of quality of service, I think that I would like clarified this point, and here I refer mainly to what Ali was saying, no-one is asking money for the small over the top that's operating for Africa, or from Kenya. On the contrary. We see the things in a completely different way. Because as Patrick was saying Google is capable to invest, and is one of few that's capable to invest because it is incumbent over the top. Google is very big and that's the capacity to invest. Therefore the capacity to deliver content and using the content to deliver and to invest, and to ensure that their services have a different speed, a different -but what happens to the small over the top, to the new company that they cannot make such kind of investment? And we as operators, we're not asking you money, we're not asking them, we're asking let's work together, and let's do revenue sharing. We'll not ask -- so this means that with the quality of service we'll allow, even the smallest player in the market, to offer new service to compete with big, other big players, without making investment, because we'll do the investment, and we'll share with them the revenue, we'll share with them the model, and so on the contrary, we think that this system could create more competition and could allow small and new players to enter into the market and to be competitive, and to offer new service. So this is the first point. I would like to have your reaction on this. The second one, first I want to say that I agree 95% with what Robert has said, also because we've to thank what he did, he does, is doing, and because of Cisco also is important, to demonstrate how this business is changing, the boom of traffic and the reality of the changes that there are, but just to clarify two points, first, we believe in the private sector, and we believe in commercial agreements. We're against any further regulation. Just to be clear on this point. Second, as far as I know, Robert, in the US, already the sending-out of (sound bad) and is implemented in the US (sound bad) and another thing which the last comment that is from here, I have some difficulties to -- I think you made a very good point, a very important one. Choice of the customer is the most important thing. You are not happy, you change your provider. You are not happy, change it. You can do that in Europe. You can do that. You know how many providers there are in France and in other countries. This demonstrates that even, you know, that in Europe, there is a lot of possibility to check the minimum level of quality service, go to the regulator, and I think that what you said is extremely important, and demonstrates how important it is to keep such kind of competition and this is the reason why no-one is interested to lose a customer. Because we want to keep our customers. Thank you very much. >>: Thank you very much Luigi. I think a couple of people on the panel probably want to respond to that. It is interesting, because of course it echoes many of the points that have already come up in the panel discussion, including the notion of win/win and the notion of voluntary commercial arrangements. Anyway, Robert, why don't you go? >>: I think your point about small content providers is actually extremely important, because that's actually why I made the point about the Amazon service, because the analogy here, it is more of an an allergies which is just that Google bias (inaudible) goes to Amazon to buy computing on an as needed basis, right, as they need it. So the analogy, and it is more than an analogy is that for CDN the large operators can build their own CDNs. Actually the CDNs provided by third parties, or by the traditional telecom operators, are a huge opportunity and a sweet spot to create a new business relationship that benefits the new entrant that only can afford to buy CDN capacity, right? They buy it by the drink not by the bottle, or the by case, right? They buy it as they need it, so it is a business opportunity, and it is very analogous to what Amazon has done in the computing space with computing as a service, into the CDN space, so I think that that's extremely important, and by the way, there are operators that are doing that today. The second point you make about sending network -- those are commercial arrangements. In fact, there can be all kinds of commercial arrangements. It is the regulatory mandate, in fact I remember when I was at the FCC, Scott may remember this as well, we had mobile operators come to us wanting us to impose calling party pays, and we said no. There is nothing to prevent you from doing it. You want to do that, that's fine. We're not going to require it. Right? They ended up never doing it, because the business model actually worked out better for them with the bill and keep, but, you know, having -- when you are talking about commercially-negotiated arrangements, there is going to be a wide range. The majority of the Internet peering and transit relationships in the US, especially the -- are not, you know, the sending network pays arrangements, although if you can think about some of the paid pairing or transit, you are, because there is a symmetry in traffic, we can get into the whole peering thing, and Scott actual slee one of the world's experts on peering because he negotiated some of the earliest peering contracts among the big, big network operators, back in the nineties, but no, I think you are absolutely right Luigi. That's what you want. You want the degrees of freedom to have this commercial negotiation. >>: If I can offer a data point since I was or the sort of invoked there, at the point when I was in industry negotiating agreements I was doing that for G T E which became part of ver eyes on of course and it is probably the third or fourth largest backbone in the world, about 10% of our private peering arrangements involved payment. 90% were settlement free, so it has existed actually from the very earliest days of the Internet but it has never been a dominant model. Okay. Yes, Taylor, I think. >>Taylor Reynolds: Thank you very much. I would be happy to address Luigi's comments because I think they play right into this whole discussion about two-sided markets. One thing for those of you that may not be as current on what is going on with some of these discussions is that operators are saying hey, we've to upgrade our networks, and we need to pay for them, and it is true, there are network upgrades and they need to be paid for. One of the discussions going on, though, is if the existing revenues are enough, or more than enough, or not enough to cover these upgrades. TelCos have massive amounts of revenues coming in compared to companies like Google, other Internet providers. I mean, they are very large, and the question is who is going to pay for this? My fear, though, in terms of the two-sided market is that the proposals that are out there, some of them that have been tabled, are actually taking us back to a model for the way things used to work for mobile and fixed line telephony. As I pointed out earlier in the day in this discussion here, it doesn't make any sense that if you pick up Skype and you make a phone call to the US you pay 1 per cent a minute to call via Skype to the US but you pay 3 8 cents to call Ghana that's a result of the structure that has been put in place by the government of ga in a to tax things coming in, and a cartel that has essentially been built in ga in a for mobile termination. We don't want to go down that road in terms of the Internet because look at the people who are affected by this. It is not the Americans, like I am, it is the person who is calling back to ga in a and calling -- paying 38 cents a minute and cannot afford to call their families while they are away. We need to be very careful so that's why the two-sided market changes and you think I am going to raise some revenue inside my government by putting a tax on mobile termination. What you are doing is actually affecting the whole ecosystem in ways that are going to be very detrimental for a country like ga in a. >>: I would entirely agree with Taylor on this. I mean, we already are seeing a situation where we're starting to ball can eyes the Internet. I think what we just said, I think my biggest contention here is where do you draw the line. Why do you say that (Inaudible) from a Kenyan perspective that's a start up. Where do you draw the line and say that the TelCo in Mongolia which they are downloading my three racer doesn't know that this is actually a start-up that may not have, necessarily, the money to make these, to do this revenue share that you are proposing. I mean, I think the point here is the principle behind this. We need to be very careful. I'm not in total disagreement that the TelCos are making investments this somebody somewhere must pay for but we must be very careful how we structure this, and how we get into a situation where we're actually putting these into government-related treaties that then become an issue where certain markets are going to be totally discriminated from a price perspective, so that's really, from a perspective of a guy who is coming from Kenya, who is seeing the kind innovation that's happening, this will just kill innovation. Pop immediately. Those are the concerns that we have. >>: Why don't we take that one first? You've got the microphone. Go for it. >>: I'm just going to claim it as I have it. Thank you Chair. My name is (Inaudible) I'm a consultant from The Netherlands, but I would like to respond to Mr. G I think your name is, that as an analysis, something which happened in the Netter hands in February and March of this year, microprocessor chips are one of the biggest chings that driving these things et cetera, the machines that make them are being made by a company in a small village in The Netherlands which is the world leader and they could not afford to invest the new generation of machines all by themselves, and the banks apparently at this stage of time were not willing to invest with them. They got their biggest customers so far that they bought 10% each of shares into the company which the company can invest with to build the generation machines that they deliver Intel and others to make the chips they need two years from now, so in other words that could be a model and he is putting off his headphones which is very bad because it is a message to him, you better keep your headphones on, right, he got customers to invest into your companies to build the new generation network, so look to people like Google and Microsoft and Yahoo and whoever they are, maybe they are willing to invest with you because they can deliver better content, et cetera. This is what I think they are called ADS L or something, am S.L., and they actually did that. As an ex-regulator, just one word on regulation, that we basically broke open the market in The Netherlands and you can see through the years, step-by-step, the regulation went backwards and innovation is all over the place, but with lower interconnection rights and special access rights within a few years and we saw that the companies went way beyond the regulation ever envisioned, so in other words, regulation helps to break open a market from an uncouplebant situation, but after that only regulate what you need to regulate. I think that's the message. >>: That's a good message. Let's take a few more questions if Mr. G has a comment at the end, I will be happy to take it. >>: Hi, I'm (inaudible) I think that in developing countries and in South America, Argentina, in particular, the co-ordination costs involved in creating IXPs, for example, or the transaction costs that we would need for small content providers in order to be online and to have their services, they will be huge. I mean, so I don't -- well I don't agree with the proposal in that respect because why think it helps developing countries at all and I think we've to watch out for co-ordination and transaction costs in these developing markets and in fact if you see the broadband, the national broadband plan in Brazil, the national broad band plan in Argentina they are just being run by the government because the holistic market of the operating TelCos is not helping that access go into the least central regions of both these two huge countries, so just these two comments. >>: Okay. Good. Why don't we -- the gentleman in the back, from whom we stole the microphone a while back, why don't we get it back to him now? >>: Thank you (Inaudible) international centre for journalists, and I'm talking about for the CDN content that we need, and we can -- example for Africa, we tried so many times to provide content that it is an NG O content. It is done for good, or a disaster content, in a we're trying to help citizens with it, and in that case, we don't need to wres he will with operators about fees. We should have some kind of regulatory here to help these people to send their content to help other citizens. Thank you. >>: Thank you. I'm going to want to do a last run around the panel. Luigi, was there anything that you felt the need to respond to out o of those? I'm not sure you did, but if you wish to, you are welcome to. Okay. Why don't I simply offer it to the panelists then, do you have any close remarks or wrap-ups? I know that I have got some thoughts that I come away with from this. Patrick first? >>: Having an arm wrestling match together for the future of the Internet. Okay. All right. Well, let me just wrap up with my final comments before you do that, and I just wanted to say that I think this was an excellent exchange, you know, the idea of revenue sharing and having small businesses share business models, I think is a very good suggestion, and that's one that is available today on the market right? Anybody can do that. Anybody can choose to enter into a revenue sharing relationship with any company, whether it is an I SP or a TelCo or any of the larger platforms, and, you know, that's the beauty of the market, and again, I think that speaks to the permissionless innovation. What we really want to avoid is having rules or mandates that require revenue sharing. It sounds like we agree on that point, but I think that's just an important thing to emphasise at least from my perspective. >>: I would like to first say something, because otherwise we'll give the wrong impression. We're friends with Patrick. We're not enemy, and I have to say that also our relationship, not only between us, but in general with Google are improving a lot, and the dialogue, the discussion, is always good, is always important, because there is also, behind a better comprehension of the situation, and what we've to understand that this discussion is much broader than the discussion we're having to date. Let's think about, we've a complete revolution. Let's think about what has happened with the publisher for example. The business model of the publisher has to change. It is changing dramatically for the broadcaster it will be the same. So it is not only about telecom operators and Google, it is much more broad, and obviously we've -- we don't want to stop the future. The future, we'll not block the future. We've to understand, we've to adapt and we've to work in order to have a better Internet for everybody in a way in which everyone will win. Starting from the users because we speak too much about, not only about us but we should always remember first we should speak about consumer user and then about the industry, because what we need is a model that work well. And so I don't feel very far from you Patrick, even if we can have different ideas, but we're here, and what I like in this IGF that has been said several times, we need to work together. We're here to work together. Thank you very much. >>: Thank you very much Luigi. Moving around the panel, a Ali Hussein? >>: I think for me Luigi has just said what I really wanted to say, because this is an ecosystem, and the more we -- I like this new American word that is being bandied around quite a bit,, "", so you know you are friend and enemy statement. You compete but at the same time you cooperate. So I think if we have this kind of agreement, arrangement, rather, where you've not a win/lose situation, not a zero-sum game but a win/win situation across the board I think we'll have, you know, a better engagement. >>: Well said. We also speak about C as well. Competition and could opration at the same time. >>: What are some of the government policies that could address some of these issues about investment? One of them could be we need to make roll out easier, so that will be (Inaudible) and we also need to have develop content. We need to foster the development of content locally, and we need to keep it local, and governments need to do their part to put their own public sector information available on line to increase demand for the Internet. >>: Very good thoughts. Thank you. Robert? >>Robert Pepper: I will also be brief because based upon the experience of the last two days, three days, if we're not in line for food they run out of food. >>: That's brief. Thank you. >>Scott Marcus: Okay well let me take the moderator's privilege of trying to wrap up what we heard over the last hour-and-a-half. We actually had, I think, agreement on quite a few points, so let me see if I can rattle them off. One was that this is an ecosystem as a whole and that everybody has to make money and that there is a need to look for win/win kind of solutions. Another point where I think was broad agreement is the need for voluntary commercial arrangements, not for a regulatory solution. A third point that we heard at a couple of instranses is that there is quite a bit that can be done to improve the system, you know, quite independent of this two-sided market discussion, everything from making sure that there is sufficient international band width, Internet exchange points, proper arrangements within countries, and so on. I think a fourth is sort of a broad concern about radical or imposed change to the system, unintended consequences, transaction costs and so on. And I think that's actually pretty of what I have got. As I said, it is a desire to try to find ways to move forward to benefit everybody and that don't radically shake things up. >>: Scott, I think that's actually a great summation and I want to thank you very much for chairing it. It was a great panel. I appreciate it thanks. >>: Thank you. I would like thank all the panelists and our extra panellist as well, Luigi. Thank you.