Study Advice Service Plurals Author: Peter Wilson English grammar

advertisement

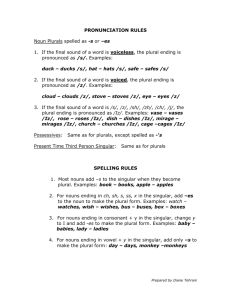

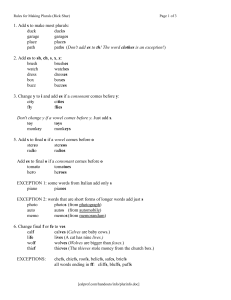

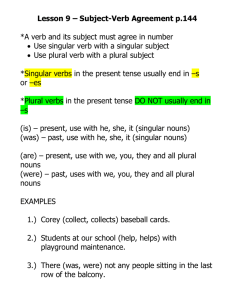

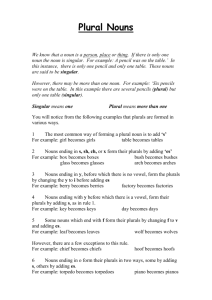

Study Advice Service Plurals Author: Peter Wilson English grammar is very simple, by comparison with that of many other languages. For one thing, nearly all nouns (= names of things) form their plurals by adding -s (or -es) – the regular plural form. There are some irregular plurals in native English – for example, child children, goose geese, woman women, sheep sheep; but the vast majority of nouns form their plurals regularly. In other languages, there are several different ways of forming plurals. Each group of nouns in a given language whose singular ends in one way tends to form its plurals in a particular, regular pattern. But another group, with a different singular ending, will normally form its plural in a different regular pattern. In academic English, many words come from such languages. Most are from Latin and Greek, the ancient languages of Rome and Greece which were for centuries the languages of University teaching. Many of these words form plurals in ways other than using -s. These plurals may be perfectly regular in the original languages, but they look irregular in English. If you want to use academic vocabulary well, you should use the correct plurals of these words. Sometimes these are the forms from the original languages; sometimes they are not. Gosh, academic English is difficult sometimes! In the beginnings of modern science, much use was made of Latin and Greek to supply words for new discoveries. In biology, all students should know the Linnaean system of naming each group of living things by reference to its species and genus, etc. The names are nearly always in a Latin form. Higher levels of the Linnaean system are often in the forms of plurals – mammalia is the Latin for ‘mammals’, flora for ‘(the goddess of) flowers’, and arthropoda for ‘spiders’. Words from the Linnaean system are not covered further in this leaflet: books on Biology, and particularly taxonomy, should supply you with all that you need. In astronomy, many stars are known by Latin (or, more rarely, Greek) names. These sometimes have modified endings: the constellation Centaurus (the centaur) has a star called proxima centauri. This means ‘the nearest star of the centaur’ – the ending -i here shows a possessive. In meteorology, some kinds of cloud are known by Latin names ending in -us (e.g. cumulus) in the singular, and -i in the plural (cumuli). The clusters of stars that look like clouds are nebulae in the plural; one is a nebula. In medical subjects, topics felt to be taboo were often “buried in the decent obscurity of a learned language” (Oscar Wilde). If you are studying in a medical field, you may need to use such terms (e.g. excreta and genitalia), but if you are, you should be taught them as your studies proceed. Law, too, is a subject whose vocabulary owes a great deal to Latin. Both Anglo-Saxon and European (“Roman”) systems derive material from the lawgivers of the Roman Empire. So there are many words and phrases, like ius (plural: iures), lex (leges) and ultima ratio regis (ultimae rationes Web: www.hull.ac.uk/studyadvice Email: studyadvice@hull.ac.uk Tel: 01482 466199 1 regis), whose pluralisation you should learn through your course. (It is usual to mark words and phrases that are clearly ‘foreign’ by printing them in italic. Words that have been absorbed into English, however, do not have italics – no matter how un-English their plurals are.) History and archaeology often examine aspects of Roman and Greek culture. So they use appropriate vocabulary – often with great care for grammatical accuracy. Remember, too, that until the Protestant reforms of the 16th Century, Latin was the language of all Christianity – and thus of most literacy and education. In the “Roman” Catholic church, it was used until the 1960s. So religious subjects also tend to use Latin with more care than most others. Some examples of foreign plurals used in academic English. Words that ended -ex or -ix in Latin had a plural in -ices (pronounced with two syllables, ‘-i-’ as in ‘in’, and ‘sees’). In academic English, we can see this in such words as appendix/appendices; index/indices; helix/helices; vertex/vertices; vortex/vortices; and codex/codices. (If you do not know these words, don’t worry. If you need to know them to study your own subject, you will know them. If you don’t need to know them, pass on your way rejoicing.) Words that end in -is, like crisis, emphasis and thesis form plurals in -es: crises, emphases and theses (and hypotheses and syntheses). Words that ended in -um in Latin formed their plurals in -a. These include such words as curriculum, which gives the plural curricula; and an adjective curricular (don’t allow your spellchecker to give you the wrong choice here!). A datum is a singular item of data. ‘Datum’ is a word rarely used in English though the word data, and data themselves, are essential for academic writing! (The word ‘datum’ is rather like ‘a singular statistic’. In mapmaking and related subjects, it means ‘a base line’.) The endings -anda and -enda mean ‘the things which should be done’, corrigenda and emendenda are sometimes given at the front of a reprinting of a book – they mean ‘the things that should be corrected and emended.’ In Latin, the singular would be corrigendum and emendendum – but these words are rare in contemporary English, even among the most academic of academics. Many ordinary people talk of referendums; academics prefer referenda. An agendum is a single item of business to be transacted during a meeting all of whose business will be listed on an agenda. In Physics, people talk of a quantum of energy, or, if there are more than one of them, quanta. The plurals of maximum and minimum are maxima and minima. Scholars may refer to more than one stadium or forum as stadia and fora; not many do, these days. A singular erratum may be one item in a list of errata, or mistakes. (The ending -ata means roughly ‘the things which have been done’. -atum is the singular – the thing which has been done.) One other ending that you may come across, particularly if your subject is historical or literary, is -ana. This means roughly ‘things [particularly ‘writings’] to do with’. Shakespeareana is writings, etc, about Shakespeare. The words alia (as in inter alia) and cetera (etcetera) are plurals – they mean ‘[among] other things’, and ‘[and] the rest’ respectively. (Note that et is the Latin for ‘and’, and never write ‘and etc’.) Omnia means ‘all things’, though the related omnibus is better translated as ‘for everyone’. (Its short form, in modern English, is bus.) In Greek, too, some plurals are formed in -a. (The Greek singular is usually -on.) Phenomenon is a singular. You should not write a phenomena – phenomena is a plural, and should only be used when you are talking about more than one thing that has happened. Unfortunately, there is another use, or meaning, of the ending -a. In some contexts, it shows a feminine singular. So an alumna is one female former student, where an alumnus is a male. Their plurals are alumnae and alumni respectively. (In Latin, if there are both males and females, one 2 should use the masculine form. So a group of former students from a mixed-sex school is its alumni. They may refer to their alma mater, ‘benign mother’, which is another feminine singular.) From the above, you may have deduced that the regular plural of words ending -us in Latin (masculine nouns) is -i. (Dame Edna Everage knows that the plural of gladiolus (the flower) is gladioli). Such words as radius, thus, become radii; syllabus, syllabi; and locus, loci; but other words ending in -us are neuter (neither masculine nor feminine), and end in -[vowel] + -ra, like corpus corpora, genus genera. But there are many words ending -us from Latin that make their plurals regularly in English, like surplus/surpluses, campus/campuses (or, less regularly plusses). This is a particular example of the general truth that, like so much in ‘good’ English, it’s not simple. For some words of foreign origin, it is usual (correct) to use a regular English plural -s. There is no rule to help you predict which words. You have to learn particular words and their plurals one by one. That is one illustration of the fact that students who do not know the language concerned should never try to ‘work out’ the correct forms. Table 1 in this leaflet (see p. 4) tries to give the most essential ones that students may need – or at least, have corrected by pedantic teachers – along with an idea of the system that lies behind them. It does not, of course, include every foreign plural that every student may come across. One masculine plural from Greek is still current in academic English, and presents a problem. ’Οί πολλοί is used, in its English lettering as ‘hoi polloi’. It means ‘the many’, and is used largely as a way for ‘educated’ people to mark their superiority to those who know no Greek. (This is sometimes fictional, of course: those who use it sometimes know no more Greek than a radish.) The phrase ‘the hoi polloi’ is anyway a solecism: it is equivalent to saying ‘the the many’, and thus has one more ‘the’ than necessary. ‘Loan-words’ from other languages tend not to keep their native forms in English – except among specialist students, e.g. of languages. (As in this leaflet, the use of original forms is often a form of showing off. But it is showing off that impresses academics. So I recommend it to you.) In modern European languages, French nouns and adjectives have regular plurals, like English, with -s. Some whose singulars end in -u form plurals in -ux. Sometimes, where the masculine is –f, the feminine is – ve (e.g. naif/naïve). Italian is a language that has given us many of our words to do with music and the visual arts. Many end in -o in the singular. In Italian, most become -i in the plural. English musicians are not consistent in the way they have used these terms. If you are studying music, you’ll pick up the difference in usage as you go along - I trust! Others might notice that cello can be pluralised as celli or cellos; we have sets of concerti (~ concerto); more than one piccolo are piccolos, never, to my knowledge, piccoli in English; and so on. Table 1 shows a few of the words that English has taken from other languages that are most often found in the singular. In formal academic English, it is usually seen as correct to use the foreign plural forms. So these are given where we think they may be useful. 3 TABLE 1 Singular Plural Notes abscissa addendum abscissae addenda OED also records abscissas. ~ ‘the things that should be added’. alumna alumnae These are the feminine forms, ~ old girl(s). alumnus analysis alumni analyses These are the masculine forms, ~ old boy(s). Don’t confuse with verb to analyse analyses. appendix appendices Better academic plural than appendixes. auditorium automaton axis auditoria automata axes bacterium cherub colloquium compendium bacteria cherubim colloquia compendia OED also records compendiums. consortium consortia continuum corpus continua corpora crisis crises criterion curriculum criteria curricula dictum dicta emphasis erratum focus emphases errata foci Don’t confuse with to emphasise forum fora Many people say forums. fungus ganglion fungi ganglia Colloquially, sometimes funguses. genus genera helix helices hypothesis incunabulum index locus maximum hypotheses Don’t confuse with verb to hypothesise. incunabula Better academic plural than indexes. indices loci Note adjective maximal. maxima medium minimum media minima nebula nebulae opus opera Musical plays use ‘the works’ to move the audience. persona personae - and personae non gratae. OED also records automatons. Maths (~ turning point; graph line); History (the Axis = Germany, Italy, Japan in W.W.II). N.B. a single tiny thing is a bacterium. Academic religious contexts. Children are cherubs. The adjective is curricular. emphasises. Also focuses; in U.K. often ‘irregular’ focusses. Note adjective minimal. 4 phenomenon phenomena postscriptum -scripta Academics may add several post scripta to a letter. Others have postscripts. OED records quantums. quantum quanta radius radii Also referendums. referendum referenda “rarely rostrums” OED. rostrum rostra In academic religious studies. seraph seraphim Singular and plural are the same. series series simulacrum simulacra Singular and plural are the same. species species spectrum spectra Still better in academic English than stadiums. stadium stadia stimulus stimuli stratum strata Better in academic writing than syllabuses. syllabus syllabi synthesis syntheses - and verb to synthesise. thesis theses Mostly archaeological. tumulus tumuli Ultimatums also exists. ultimatum ultimata vertex vertices vortex vortices Some words are essentially used in English only in their plural form. Some of these are: TABLE 2 [It may help to know that et in Latin (and French) means ‘and’.] Usual (plural) form Original Singular Comments agenda agendum = the things that are to be done. alia arcana [alium] arcanum = other things. cetera [ceterum] = the other things. corrigenda data corrigendum datum = the things that should be corrected. delenda delendum = the things that are to be deleted. emendenda emendendum = the things that should be changed. impedimenta impedimentum = baggage. The Latin singular ~ impediment. marginalia miscellanea marginalium miscellaneum = miscellany. paraphernalia = ‘the secret things’, only revealed to initiates. The singular datum is rare nowadays. There is a singular – paraphernal. But it is rare. All web addresses in this leaflet were correct at the time of publication The information in this leaflet can be made available in an alternative format on request. Telephone 01482 466199. © 11/2007 5