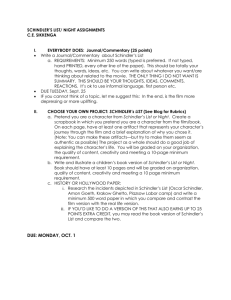

schindler's list

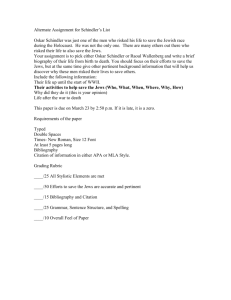

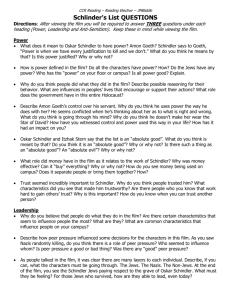

advertisement