Analysis of Truman: By James H - James

advertisement

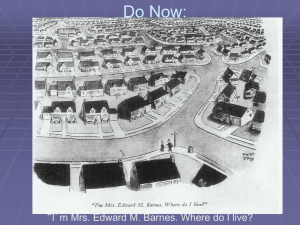

Analysis of Truman: By James H. Boyd The year is 1948. The sulfurous smell of burning coal mingles with the fragrant essence of honeysuckle and wildflowers as the large rural crowd gathers for yet another “whistle-stop” campaign rally for the thirty-third President of the United States, Harry S. Truman. Soon, they are witnessing the plainspoken “Man from Missouri” at his “give ‘em hell” finest: Extolling the glories of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal while lambasting what he perceives as greed and corruption within the Republican ranks. Afterwards, he shakes hands and socializes with the friendly crowd, then goes off to the next stop. Whenever the name of Harry Truman comes up in conversation, sentimental images such as these are often what come to the imagination. Truly, President Truman was “one of us,” a humble, simple product of small town origins who rose from obscurity to the highest office in the Land, overcoming seemingly impossible odds every step of the way. It is an inspirational story, to be sure, but one which frequently downplays the complexity and intellect of the man himself. Fortunately, those interested in a more thorough, balanced look at President Truman’s life and legacy can easily look to David McCullough’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, simply entitled Truman. First and foremost, McCullough writes as an historian, passionate for his discipline while constantly looking for ways to make it relevant for modern readers. In a 1981 interview with Paul Giambarba, McCullough outlines his personal approach to history: History is the story of people. ..Very few professional historians are, at heart, interested in people. And that's one of the reasons that so much that is written in the way of history, and in the teaching of history, is boring. I can't tell you how many people have come up to me and said, "Oh, if history had only been taught like that when I was in school, I would have become a history major." Well, there isn't any other way to do it, in my view. That's what history is, and the crucial thing is to feel, not just to know, but to feel that people of the past were just as real, just as alive, just as prey to the same emotions, fears, exhilarations -- whatever -- that we are. And the only thing that is different is their time was different from our time, but they didn't think they were living in The Past (1). Consistent with this philosophy, McCullough presents President Truman as both a heroic and as a paradoxical figure. He was a public servant with a solid sense of right and wrong, despite early associations with corrupt political bosses. He was a civil rights champion who never completely overcame his own personal prejudices. And he was a leader whose fierce loyalty to his close friends bordered on naïveté, which caused nearly catastrophic damage to his administration. It is with this in mind that we will examine McCullough’s classic work in light of insights from some of the most respected minds in modern political thought, scholars such as Clinton Rossiter, Richard Neustadt, Samuel Kernell and numerous others. As we look at various events in President Truman’s fascinating life and career, we will see how his actions and abilities “stack up” in light of their critical analyses. The events of April 12, 1945 are now the stuff of legend. Vice President Truman joins House Speaker Sam Rayburn for drinks and conversation to close out the work day. Suddenly, they are interrupted by a phone call for Truman to come to the White House as “quickly and quietly” as he could. There he is greeted with the bone-chilling news of President Roosevelt’s passing. Truman’s timely response that the weight of “the moon, the stars and all the planets” had fallen on his shoulders was no simple hyperbole. For Truman to replace such a revered leader at such a crucial point in history was beyond the grasp of imagination. As presidential scholars Sydney Milkis and Michael Nelson observe: … the contrast between Truman and his predecessor was striking…A poor speaker who was awkward in the presence of reporters, Truman suffered persistently low popularity…In other respects, however, Truman was a solid successor to Roosevelt. He believed deeply in the changes that the New Deal had made in the United States. Although he was all too aware of his personal limitations, Truman also recognized the legacy of FDR’s active personal style and of the expanded government responsibilities that Roosevelt had brought about required active presidential leadership from his successors (2). Regardless of one’s political persuasion, it is impossible not to sympathize with Truman at this crucial hour. It is here that we will begin the primary focus of this work. Although there are many facets of Truman’s presidency which would make for a fascinating study, I will focus primarily on four. We will first look at the Truman Doctrine, an international strategy which is widely viewed as initiating the Cold War. Then we will follow with a discussion of the Marshall Plan, which revitalized the structure of post-World War II Europe. Then, we will examine Truman’s groundbreaking work in the area of civil rights. Finally, will take a look at his dramatic reelection victory in 1948, and finish with an overview of his post-presidential life and long-term legacy. The Truman Doctrine In assuming the presidency at the time that he did, it became Truman’s unenviable duty to be Commander-in-Chief of a nation in the bitter throngs of World War II. This culminated in both the fall of Nazi Germany, and the heart-wrenching decision to use the Atomic Bomb on Japan, thus bringing the War to a bloody, but victorious conclusion. However, the feeling of security that followed was not to last long. Although initially seen by Truman as a trusted ally, Joseph Stalin’s ruthless grip on Communist Russia cast an ominous shadow over post-war Europe. In was under this shadow that, on February 27, 1947, President Truman received word that, due to severe economic conditions, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee was withdrawing forty thousand troops from Greece, and ending all economic support, with the hope that the United States would assume the responsibility (3). This would leave Greece in dire straits, as the British had been aiding them in a bloody civil war with Communist guerillas. Newspaper publisher Mark Ethridge would later describe Greece as a “ripe plum” ready to fall into Soviet hands (4). Also in a grave condition was the Nation of Turkey. General Walter Bedell Smith, the American ambassador to Moscow, stated that Turkey had “little hope of independent survival unless it is assured of solid long-term American and British support (5).” President Truman made his dramatic appeal to Congress on March 12, 1947. Laying the foundation for later Cold Warriors such as Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan, he presented his case in no uncertain terms: The peoples of a number of countries of the world have recently had totalitarian regimes forced upon them against their will. The Government of the United States has made frequent protests against coercion and intimidation in violation of the Yalta agreement in Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria. I must also state that in a number of other countries there have been similar developments. At the present moment in world history nearly every nation must choose between alternative ways of life. The choice is too often not a free one. One way of life is based upon the will of the majority, and is distinguished by free institutions, representative government, free elections, guarantees of individual liberty, freedom of speech and religion, and freedom from political oppression. The second way of life is based upon the will of a minority forcibly imposed upon the majority. It relies upon terror and oppression, a controlled press and radio, fixed elections, and the suppression of personal freedoms. I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures. I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way. I believe that our help should be primarily through economic and financial aid which is essential to economic stability and orderly political processes (6). This fiery speech earned the President a standing ovation. Subsequently, the press response was very positive. The New York Times compared it to the Monroe Doctrine. Life magazine said the speech was “Like a bolt of lightning.” Likewise, Collier’s said that Truman had “hit the popularity jackpot (7). “ However, there were also significant reservations expressed toward the message. For example, PM accused the President of scarring Roosevelt’s entire Russian policy (8). Members of Congress on both sides of the isle expressed concern over the economic ramifications, as well as the effect on future relations with Russia (9).Samuel Kernell, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, sums it up well: After having experienced the cold war rhetoric of the 1950s, one may not find much in Truman’s statements that is particularly arousing or inflammatory. But it must be remembered that this was the first time a president had publicly identified the Soviet Union as an enemy and depicted so starkly the struggle between democracy and totalitarianism (10). So did Truman’s speech, in and of itself, usher in the Cold War? Kernell observes that these sorts of claims seem to be overstated: Large numbers of citizens rallied behind the president’s legislative proposals, but there is little evidence that the speech triggered a massive, domestic anticommunist phobia or exploited anticommunism already prevalent I the country at the time. The effects of President Truman’s speech on public opinion are, therefore, consonant with the conventional wisdom of politicians rather than with history…Instead, (his) capacity to lead the nation into a new, foreboding era of foreign affairs reflected in large part the citizenry’s trust in him as its leader (11). McCullough further emphasizes that, in spite of Truman’s staunch anticommunist convictions, he adamantly refused to take part in the stateside conspiracies of mass Communist infiltration, stating that “Much too much was being made of the ‘Communist bugaboo.’” and that the country was “perfectly safe so far as Communism is concerned-we have far too many sane people.” Nonetheless, to protect his administration from accusations of being “soft on Communism,” Truman did later establish a Federal Employees Loyalty and Security Program, stating that “I am not worried about the Communist Party taking over the government of the United States, but I am against a person, whose loyalty is not to the government of the United States, holding a government job (12).” Politically, these actions were a strong clarion call to congressional Republicans, who, according to Time magazine’s Capitol Hill correspondent Frank McNaughton, were “now taking Truman seriously…The Republicans are beginning to realize Truman is no pushover (13).” When it was time for action on Capitol Hill, the results were dramatic. McCullough describes the scenario: On April 22, 1947, the Senate overwhelmingly approved aid to Greece and Turkey by a vote of 67 to 23. On May 9, the House, like the Senate, passed the bill by a margin of nearly three to one, 287 to 107. On May 22, while visiting his mother in Grandview, Truman sat at the Mission oak table in her small parlor and signed the $400 million aid package. The Truman Doctrine had been sanctioned (14). The Marshall Plan Richard E. Neustadt, Douglas Dillon Professor of Government Emeritus at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard, describes the Marshall Plan as “perhaps the greatest exercise in policy agreement since the Cold War began (15).” Arthur Krock, the “Dean of Washington newsmen,” would call it “the central gem in a cluster of great and fruitful decisions made by President Truman (16).” Ultimately, Truman’s policy of reconstruction in post-World War II Europe would be one of his most acclaimed contributions to history. As McCullough states: The idea of economic aid to Europe had been on Truman’s mind for some while…In his own State of the Union message in January, Truman had struck the theme of sharing American bounty with war-stricken peoples, as a means of spreading “the faith” of freedom and democracy, and on March 6, even before the announcement of the Truman Doctrine, he had said in a speech at Baylor University, “We are the giant of the economic world. Whether we like it or not, the future pattern of economic relations depends on us (17). Already upset by the indifference he had encountered during a visit to Moscow, Secretary of State George Marshall was continually receiving reports of the grave situations in Western Europe. Truman responded by sending Dean Acheson to sound a “warning bell” in a speech in which he emphasized that financial help was imperative, but the objective was not relief, it was the revival of industry, agriculture and trade (18). Receiving an honorary degree from Harvard, Marshall used this rather unusual occasion to unveil this crucial undertaking: Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist. It would be neither fitting nor efficacious for our Government to undertake to draw up unilaterally a program designed to place Europe on its feet economically. This is the business of the Europeans. The initiative, I think, must come from Europe. The role of this country should consist of friendly aid in the drafting of a European program and of later support of such a program so far as it is practical for us to do so. The program should be a joint one, agreed to by a number, if not all, European nations (19). McCullough comments that “Two ideas were new and distinguishing. He was calling on the Europeans to get together, and, with American help, work out their own programs. And, by inference, he was leaving the door open to the Soviets and their satellite countries to take part (20).” Furthermore, Neustadt points out the crucial follow-up work on the part of British foreign secretary Ernest Bevin: He well deserves the credit he has sometimes been assigned as, in effect, coauthor of the Marshal Plan. For Bevin seized on Marshall’s Harvard speech and organized a European response with promptness and concreteness beyond the State Department’s expectations. What had been virtually a trial balloon to test reactions on both sides of the Atlantic was hailed in London as an invitation to the Europeans to send Washington a bill of particulars. This they promptly organized to do, and the American Administration then organized in turn for its reception without further argument internally about the pros and cons of issuing the “invitation” in the first place (21). As McCullough further describes: With Britain’s Bevin taking the lead, a hasty conference was organized in Paris, to which the Soviets sent a sizable delegation headed by (Vyacheslav) Molotov. The provisional and largely Communist-dominated government of Czechoslovakia had already indicated that it wished to be included in the program. Communist leaders in Poland and Romania had shown interest. But five days into the conference, after being handed a telegram from Moscow, Molotov stood up from the table and abruptly announced that the Soviet Union was withdrawing. The Marshall Plan, he said, was “nothing but a vicious American scheme for using dollars to buy its way” into the affairs of Europe (22). By taking this approach, however, the Soviets played directly into the Truman administration’s hands. As McCullough further observes, “By refusing to take part in the Marshall Plan, Stalin had virtually guaranteed its success. Sooner or later congressional support was bound to follow now, whatever the volume of grumbling on the Hill (23).” The Marshall Plan went on to be passed in April, 1948 with overwhelming support from both houses of Congress. Truman would proudly recall that “In all the history of the world, we are the first great nation to feed and support the conquered…Our neighbors are not afraid of us. Their borders have no forts, no soldiers, no tanks, no big guns lined up (24). In this, one of the finest moments of his presidency, Truman epitomized Cornell Professor Clinton Rossiter’s observation that: The reasons why he, rather than the British Prime Minister or French President or an outstanding figure from one of the smaller countries should be singled out for supranational leadership are too clear to require extended mention. Not only are we the richest and most powerful member of any coalition we may enter, not only are we the chief target of the enemy and thus most truculent of the powers arrayed against him, but the Presidency, for the very reasons I have dwelled upon...unites power, drama, and prestige as does no other office in the world (25). Civil Rights Up to this point, our study has focused primarily on two key elements of Truman’s foreign policy. We will now turn our attention on one of the greatest aspects of his domestic legacy. Even early in his national political career, Truman was an outspoken supporter of civil rights at a time and place in which it was truly groundbreaking. Campaigning for the Senate before an all-white audience in Sedalia, Missouri, he stated that: I believe in the brotherhood of man: not merely the brotherhood of white men, but the brotherhood of all men before the law…Negroes have been preyed upon by all types of exploiters, from the installment salesmen of clothing, pianos, and furniture to the vendors of vice. The majority of our Negro people find but cold comfort in shanties and tenements. Surely, as freemen, they are entitled to something better than this (26). In the modern era, we generally take it for granted that our public servants, particularly the president, will echo these sentiments. Rossiter sums it up well: The people have done much to make (the Presidency) what it is today; the man who holds it reaches out to them for support and repays them with guidance and protection. There is no more impressive evidence of this truth than...the elevation of this office to a commanding position in the ongoing struggle for civil rights. We have become increasingly conscious of our shortcomings and wrongdoings in these related fields in recent years. Even as we sin against one another in the area of freedom of expression, even as we drag our feet in the march toward justice for our minorities, we feel the gaze of the whole world upon our necks and we are uncomfortable. And as we have become more conscious, the President, who has a sizable part of this world for a constituency, seems to have grown in stature as a friend of liberty (27). While Truman was definitely a pioneer in this, there were, unfortunately, some serious discrepancies between his public and private persona on this issue. As Neustadt points out, “ Truman certainly deserves to have the cause of civil rights cited among his purposes, but if he were to be judged in temperamental terms according to the standards of, say, Eastern liberals, he scarcely could be called a man of passion on the point (28).” The fact is that Truman, in spite of his rhetoric to the contrary, continued to harbor some of the old prejudices of his upbringing. As McCullough reveals, “Privately, like the country people whose votes he was courting, he still used (the “n” word) and enjoyed the kind of racial jokes exchanged over drinks in Senate hideaways. He did not favor social equality for blacks and said so.” Furthermore, his sister, Mary Jane candidly stated that “Harry is no more for n*** equality than any of us (29).” Obviously, this is a troubling aspect of Truman’s character, a serious flaw in what was otherwise a very noble life. Although some may be able to rationalize it as simply being a “part of the times” in which he lived, our modern conscience still asks how valid this excuse ultimately is. Nonetheless, Truman was in a pivotal point in time to address the issue. As Yale Political Science Professor Stephen Skowronek, observes; (Franklin) Roosevelt had seen the fight for civil rights coming, but he refused to make it his own, fearing the devastating effect it would have on the precarious sectional balance in his newly established party coalition. Harry S. Truman had seen the fight break out and temporarily rupture the party in 1948. His response was a balance of executive action and legislative caution (30). On June 29, 1947, Truman became the fist president ever to address the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Speaking, fittingly, at the Lincoln Memorial to a crowd of ten thousand, he delivered the most passionate presidential call for civil rights since Lincoln himself: When I say all Americans I mean all Americans. Many of our people still suffer the indignity of insult, the harrowing fear of intimidation, and, I regret to say, the threat of physical injury and mob violence. Prejudice and intolerance in which these evils are rooted still exist. The conscience of our nation, and the legal machinery which enforces it, have not yet secured to each citizen full freedom from fear. We cannot wait another decade or another generation to remedy these evils. We must work, as never before, to cure them now (31). As he listened, NAACP head Walter White compared Truman’s speech to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address: “I did not believe that Truman’s speech possessed the literary quality of Lincoln’s speech, but in some respects it had been a more courageous one in its specific condemnation of evils based upon race prejudice…and its call for immediate action against them.” Afterward, Truman turned to White and assured him that he “meant every word of it-and I’m going to prove that I do mean it (32).” True to his word, he had taken significant action within the next year. On February 2, 1948, much to the chagrin of southern Democrats, Truman’s Civil Rights Commission released the first ever message specifically addressing the issue of civil rights: Not all groups are free to live and work where they please or to improve their conditions of life by their own efforts. Not all groups enjoy the full privileges of citizenship… The Federal Government has a clear duty to see that the Constitutional guarantees of individual liberties and of equal protection under the law are not denied or abridged anywhere in the Union. That duty is shared by all three branches of the Government, but it can be filled only if the Congress enacts modern, comprehensive civil rights laws, adequate to the needs of the day, and demonstrating our continuing faith in the free way of life (33). In light of these convictions, Truman spoke forcefully against the barbaric practice of lynching, called for an end to poll taxes and promoted the establishment of a Fair Employment Practices Commission. He further asked Congress to act on the claims of Japanese-Americans who had been forced from their homes and placed in confinement during World War II. Asked at a press conference what he had drawn on for background, Truman simply responded “The Constitution and the Bill of Rights (34).” Dewey Defeats Truman? The image is forever fixed in our nation’s political history: President Harry S. Truman stands, newly reelected, holding up a premature edition of the Chicago Tribune announcing his defeat at the hands of New York governor Thomas Dewey. In spite of the numerous successes during his first term, Truman was in serious trouble as he ran for reelection in 1948. He was faced with a sharply divided Democratic Party and approval ratings of 36%, and his hopes of being renominated, let alone reelected, seemed almost nil. Many prominent Democrats, including Franklin Roosevelt’s son, James, were involved in a movement to draft the popular General Dwight Eisenhower as the Democratic candidate. As McCullough summarizes: He had been castigated by southern Democrats over civil rights, repudiated by a Republican Congress…Seen himself portrayed in the press as inept and pathetic. His party was broke. And now the New Dealers were abandoning him, and noisily. No president in history, not even Herbert Hoover in his darkest days, had been treated with such open contempt by his own party (35). Again, all of this seems quite ironic in light of Truman’s very impressive list of accomplishments. In a diary entry, former TVA director David Lilienthal rightly asserted that: Truman’s record is that of a man who, facing problems that would have strained or even floored Roosevelt at his best, he has met these problems head on in almost every case. The way he took on the aggression of Russia…his civil rights program, upon which he hasn’t welched or trimmed-My God! What do these people want (36)? Nonetheless, when the party gathered for its 1948 National Convention, pessimism was the order of the day. Senator Alben Barkley, the eventual Vice-Presidential nominee said that you could “cut the gloom with a corn knife. The very air smelled of defeat (37).” Later, the event was fractured even further by a nasty floor fight over civil rights that, in spite of walkout threats from southern delegations, resulted in the party drafting its first ever plant on the issue. Eventually, Truman was able to secure the nomination and gave a rousing speech promising that “Senator Barkley and I will win this election and make these Republicans like it-don’t you forget that.” McCullough states that: For the first times since 1945 he was speaking not as a leader by accident, by inheritance, but by the choice of his party. He was neither humble nor elegant nor lofty…In manner as well as content he was drawing the line so that there could be no mistaking one candidate for the other (38). And there would be no such mistaking. In start contrast to Truman, Governor Dewey was youthful, urbane and had a prestigious Columbia education. McCullough tells us that “As governor he had cut taxes, raised salaries for state employees, reduced the state’s overall indebtedness by over $100 million, and put through the first state law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment (39). In addition to Dewey, Truman also had to deal with the fringe defectors from his own party: Henry Wallace on the left, and Strom Thurmond on the right. While both Truman and Dewey were quite progressive in their political philosophies, it was up to Truman to revive the base of disgruntled New Dealers with strongly populist posturing and rhetoric. A key avenue in this strategy was the afore-mentioned “Whistle-Stop” campaign tour, in which he traveled a total of 21928 miles. His outgoing personality and genuine love of people made won him friends and supporters everywhere he went. Speech after speech was characterized by fiery reminders that “The Democratic Party puts human rights and welfare first…I’m not asking you to vote for me. Vote for yourselves…You stayed home in 1946 and you got the 80th Congress, and you got just exactly what you deserved (40).” Was this demagoguery? Perhaps, but it was also classic New Deal politics. Milkis reminds us that: The modern liberalism that became the public philosophy of the New Deal entitled a fundamental reappraisal of the concept of rights…Although equality of opportunity had traditionally been promoted by limited government interference in society, Roosevelt argued, recent economic and social changes…demanded that America now recognize “the new terms of the old social contract (41).” These factors did much to endear voters to the President, but ultimately, it seemed to be Dewey’s overconfidence and arrogant demeanor that was his eventual undoing. An example was the incident in which he described a train engineer as a “lunatic” and said that he “ought to be shot at sunrise. (42)” Slowly, gradually the tide began to turn in Truman’s favor. By carrying key states such as Ohio, Illinois and California as well as most of the south, Truman pulled off the most stunning upset victory in American history. Post-Presidency and Legacy The events of Truman’s second term were no less dramatic than the first: War in Korea, an assassination attempt and bitter clashes with Generals MacArthur and Eisenhower. He remained a controversial figure, leaving office with record low popularity. In his farewell address, Truman nonetheless reminded the Nation that: The American people stand firm in the faith which has inspired this Nation from the beginning. We believe that all men have a right to equal justice under law and equal opportunity to share in the common good. We believe that all men have the right to freedom of thought and expression. We believe that all men are created equal because they are created in the image of God…From this faith we will not be moved (43). Afterward, Truman quietly retired to his Missouri home, refusing to capitalize on his status as a former president. In doing this, he set a wonderful example that is all too often ignored by politicians today. Over time, historians have come to view Truman in a much more favorable light. Rossiter observes that: Mr. Truman kept the pressure turned on throughout his eight years, even when his hopes of accomplishing anything constructive must have been entirely empty, and by the end of his second term even the Republicans in Congress professed an eagerness to have his thoughts on such red-hot issues as labor, taxes, inflation, and education (44). At the same time, he also notes that: I confess manfully, with dragging feet, that Harry S. Truman will eventually win a place as President alongside Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt. There will be at least a half-dozen Presidents strung out below him who were more able and large-minded, but he had the good fortune to preside in stirring times and will reap large credit for having survived them…I cannot, in good conscience, predict the greatness of Washington, Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, Wilson, and Jackson for his name. Certain deficiencies of intellect and perception must always bar him from the seats of the mighty (45). Four days after becoming President, Truman told a joint session of Congress that he desired “only to be a good and faithful servant to my Lord and my people.” Opinions may differ concerning his success in these endeavors, but few will doubt that the integrity, diligence and courage that characterized his life still stand as an example for people of all ages, creeds and political persuasions. After all, the buck stopped there. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1-Giambarba, Paul. Paul Giambarba Photo and Article: Interview with David McCullough. © 1981, 2006 by Paul Giambarba. http://www.giambarba.com/mccullough/mccullough.html , August 4, 2007 2-Milkis, Sidney M. Nelson, Michael. The American Presidency: Origins & Development: Third Edition. © 1999. Congressional Quarterly, Inc, Washington D.C. pp 277-278 3-McCullough, David. Truman. © 1992 by David McCullogh. Simon & Schuster, New York, NY. pp 539-540. 4-Ibid. p 540. 5-Ibid. 6-Kernell, Samuel. Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leadership. © 1997. CQ Press, Washington, D.C. p 192 7-McCullough, p 548 8-Ibid, p 549 9-Ibid 10-Ibid. p 193. 11-Ibid. p. pp 206-207. 12- McCullough, pp 550-552 13- Quoted in McCullough, p 553 14- McCullough, pp 553-554 15- Neustadt, Richard E. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. © 1990. Richard E. Neustadt. The Free Press, New York, NY. P 40. 16- McCullough, p 583 17- Ibid, pp 561-562 18- Ibid, pp 561-562 19- Quoted in McCullough, p 563 20- McCullough, p 563 21- Neustadt, p 43 22- McCullough, p 565 23- Ibid 24- Quoted in McCullough, p 583 25- Rossiter, Clinton. The American Presidency. © 1960 by Clinton Rossiter. Mentor Books, New York, NY. p 37 26- McCullough, p 247 27- Rossiter, p 117 28- Neustadt, p 170 29- McCullough, pp 247, 588 30- Skowronek , Stephen. “Presidential Leadership in Political Time.” Michael et al. The Presidency and the Political System: Eighth Edition. © 2006. CQ Press, Washington D.C. p 111. 31- Quoted in McCullough, p 570 32- Quoted in McCullough, p 570 33- McCullough, p 587 34- Ibid, p 587 35- Ibid, p 633 36- Quoted in McCullough, p 634 37- McCullough, p 636 38- Ibid, p 642 39- Ibid, p 671 40- Quoted in McCullough, pp 658-660 41- Milkis, Sidney M. “The Presidency and Political Parties.” Published in Nelson, p 342. 42- McCullough, p 697 43- Truman, Harry S. Farewell Address. January 15, 1953. www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/harrystrumantrumanfarewelladdress.html. August 9, 2007. 44- Rossiter, p 106 45- Ibid, p 153