The impact of ICT on tertiary education

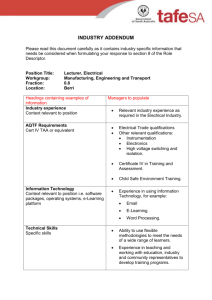

advertisement

The impact of ICT on tertiary education : advances and promises Kurt Larsen and Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Directorate for Education / Centre for Educational Research and Innovation* DRAFT OECD/NSF/U. Michigan Conference “Advancing Knowledge and the Knowledge Economy” 10-11 January 2005 Washington DC ABSTRACT: The promises of e-learning for transforming tertiary education and thereby advancing the knowledge economy have rested on three arguments: E-learning could expand and widen access to tertiary education and training; improve the quality of education; and reduce its cost. The paper evaluates these three promises with the sparse existing data and evidence and concludes that the reality has not been up to the promises so far in terms of pedagogic innovation, while it has already probably significantly improved the overall learning (and teaching) experience. Reflecting on the ways that would help develop e-learning further, it then identifies a few challenges and highlights open educational resource initiatives as an example of way forward. The first section of the paper recalls some of the promises of e-learning; the second compares these promises and the real achievements to date and suggests that e-learning could be at an early stage of its innovation cycle; the third section highlights the challenges for a further and more radically innovative development of elearning. * E-mail: Kurt.Larsen@oecd.org; Stephan.Vincent-Lancrin@oecd.org; 2 rue André Pascal 75775 Paris Cedex 16 1 2 Knowledge, innovation and Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) have had strong repercussions on many economic sectors, e.g. the informatics and communication, finance, and transportation sectors (Foray, 2004; Boyer, 2002). What about education? The knowledge-based economy sets a new scene for education and new challenges and promises for the education sector. Firstly, education is a prerequisite of the knowledge-based economy: the production and use of new knowledge both require a more (lifelong) educated population and workforce. Secondly, ICTs are a very powerful tool for diffusing knowledge and information, a fundamental aspect of the education process: in that sense, they can play a pedagogic role that could in principle complement (or even compete with) the traditional practices of the education sector. These are the two challenges for the education sector: continue to expand with the help (or under the pressure) of new forms of learning. Thirdly, ICTs sometimes induce innovations in the ways of doing things: for example, navigation does not involve the same cognitive processes since the Global Positioning System (GPS) was invented (e.g. Hutchins, 1995); scientific research in many fields has also been revolutionised by the new possibilities offered by ICTs, from digitisation of information to new recording, simulation and data processing possibilities (Atkins and al., 2003). Could ICTs similarly revolutionise education, especially as education deals directly with the codification and transmission of knowledge and information – two activities which power has been decupled by the ICT revolution? The education sector has so far been characterised by rather slow progress in terms of innovation development which impact on teaching activities. Educational research and development does not play a strong role as a factor of enabling the direct production of systematic knowledge which translates into “programmes that works” in the classroom or lecture hall (OECD, 2003). As a matter of fact, education is not a field that lends itself easily to experimentation, partly because experimental approaches in education are often impossible to describe in precisely enough to be sure that they are really being replicated (Nelson, 2000). There is little codified knowledge in the realm of education and only weak developed mechanisms whereby communities of faculty collectively can capture and benefit from the discoveries made by their colleagues. Moreover, learning typically depends on other learning inputs than those received in the class or formal education process: the success of learning depends on many social and family aspects that are actually beyond the control of educators. Information and communication technologies potentially offer increased possibilities for codification of knowledge about teaching and for innovation in teaching activities through being able to deliver learning and cognitive activities anywhere at any time. Learning at a distance can furthermore be more learner-centred, self-paced, and problem solving-based than face-to-face teaching. It is also true, however, that many learning activities cannot be coordinated by virtual means only. The emulation and spontaneity generated by physical presence and social groupings often remain crucial. Likewise, face-to-face exchanges are important when they enable other forms of sensory perception to be stimulated apart from these used within the framework of electronic interaction. However, the influence of distance 3 and time is waning now that the technological capacity is available for knowledge-sharing, remote access and teamwork, and organising and coordinating tasks over wide areas (OECD, 2004a). Focusing on tertiary education, this paper examines the promises of ICTs in the education sector, first as a way to better participate in the advancement of the knowledge economy, second as a way to introduce innovations. Leaving aside the impact of ICTs on the research or e-science performed by tertiary education institutions (see Atkins and al., 2003; David, 2004), we concentrate on e-learning, broadly understood as the use of ICTs to enhance or support learning and teaching in (tertiary) education. E-learning is thus a generic term referring to different uses and intensities of uses of ICTs, from wholly online education to campus-based education through other forms of distance education supplemented with ICTs in some way. The supplementary model would encompass activities ranging from the most basic use of ICTs (e.g. use of PCs for word processing of assignments) through to more advanced adoption (e.g. specialist disciplinary software, handheld devices, learning management systems etc.). However, we keep a presiding interest in more advanced applications including some use of online facilities. Drawing on the scarce existing evidence, including a recent survey on e-learning in postsecondary institutions carried out by the OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI), it shows that e-learning has not yet lived up to its promises, which were overstated in the hype of the new economy. ICT have nonetheless had a real impact on the education sector, inducing a quiet rather than radical revolution. Finally, it shows some possible directions to further stimulate its development. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: the first section recalls some of the promises of e-learning; the second compares these promises and the real achievements to date and suggests that e-learning could be at an early stage of its adoption cycle; the third section highlights the challenges for a further development of e-learning and shows what directions might be the most promising for its further development. I. Advancing knowledge and the (knowledge) economy: the promises of e-learning The emergence of ICTs represents high promises for the tertiary education sector (and, more broadly, the post-secondary education sector if one takes into account their impact on nonformal education). ICTs could indeed play a role on three fundamental aspects of education policy: access, quality and cost. ICTs could possibly advance knowledge by expanding and widening access to education, by improving the quality of education and reducing its cost. All this would build more capacity for the advancement of knowledge economies. This section summarises the main arguments backing the promises. E-learning is a promising tool for expanding and widening access to tertiary education. Because they relax space and time constraints, ICTs can allow new people to participate in tertiary education by increasing the flexibility of participation compared to the traditional face-to-face model: working students and adults, people living in remote areas (e.g. rural), non-mobile students and even foreign students could now more easily participate in education. Thanks to ICT, learners can indeed study where and/or when they have time to do so–rather than where and/or when classes are planned. While traditional correspondencebased distance learning has long played this role, ICT have enhanced traditional distance 4 education enabled the rise of a continuum of practices between fully campus-based education and fully distance education. More specifically, fully online learning can allow large numbers of students to access education. The constraints of the face-to-face learning experience, that is, the size of the rooms and buildings and the students/teacher ratio, represents another form of relaxation of space constraints. ICTs indeed allow a very cheap cost of reproduction and communication of a lesson, via different means like the digital recording and its (ulterior or simultaneous) diffusion on TV, radio or the Internet. The learning process or content can also be codified, and at least some parts be standardised in learning objects, for example a multimedia software, that can in principle be used by millions of learners, either in a synchronous or asynchronous way. Although both forms might induce some loss in terms of teachers-learners interactivity compared to face to face teaching, they can reach a scale of participation that would be unfeasible via face-to-face learning. When the needs are huge, fully online learning can be crucial and possibly the only realistic means to increase and widen rapidly access to tertiary education. Some developing countries have huge cohorts of young people and too small an academic workforce to meet their large unmet demand: given training new teachers would take too much time, notwithstanding resources, e-learning might represent for many potential students and learners the only chance to study (rather than an alternative to full face-to-face learning) (World Bank, 2003). E-learning can also be seen as a promising way for improving the quality of tertiary education and the effectiveness of learning. These promises can be derived from different characteristics of ICTs: the increased flexibility of the learning experience it can give to students; the enhanced access to information resources for more students; the potential to drive innovative and effective ways of learning and/or teaching, including learning tools, easier use of multimedia or simulation tools; finally, the possibility to diffuse these innovations at very low marginal cost among the teachers and learners. Distance E-learning has not only the virtue to be inclusive for students that cannot participate in tertiary education because of time, space or capacity constraints, as it was shown above. It can also in principle offer to students more personalised ways of learning than collective faceto-face learning, even in small groups. Although learning is often personalised to some extent in higher education through the modularity of paths, ICTs allow institutions to give students to choose a wider variety of learning paths than in non-ICT supplemented institutions – not the least because of the administrative burden this would represent in large institutions. This means that students can experiment learning paths that best suit them. Moreover, e-learning can potentially allow students to take courses from several institutions, e.g. some campusbased and others fully online. This possible flexibility of individual curricula can be seen as an improvement of the overall student experience, regardless of pedagogical changes. In one word, e-learning could render education more learner-centred compared to the traditional model. A prestigious university generally has a sizeable library gathering tons of codified information and knowledge. One of the most visible impact of ICTs is to give easier and almost instant access to data and information in a digital form that allows manipulations that are sometimes not otherwise possible. The digitisation of information, from academic journals through to books and class notes, can change (and has changed) the life of students by giving them easy 5 access to educational resources, information and knowledge, as well as new data processing possibilities. But e-learning could also lead to the enhancement of quality in tertiary education by leading to innovative pedagogic methods, new ways of learning and interacting, by the easy sharing of these new practices among learners and teachers communities, as well as by more transparency and easier comparisons and cross-fertilisation of teaching materials and methods. Finally, e-learning can be seen as a promising way to reduce the cost of tertiary education, which is critical for expanding and widening its access worldwide. It might thus represent new opportunities for students having difficulties with this traditional format. Although ICT investments are expensive, they can then generally be used at near-zero marginal cost. Where would this cost-efficiency come from: the replacement of expensive brick and mortar campuses by virtual campuses; the digitisation of library materials that would save the cost of keeping huge paper collections; the improvement of efficiency of institutional management; the automation of some of the traditional on-campus activities, including some teaching. II. Living up to the promises: a quiet rather than radical revolution Has e-learning (and especially online learning) lived up to the promises outlined in the previous section? It has to some extent. The reality of e-learning has never matched its most radical promises (Zemsky and Massy, 2004): while experiments are still underway, the initial stage of over-enthusiasm has ended when new economy bubble burst about 2002. In this respect, e-learning has followed the ups and down of the new economy and given rise to the same caveats as in other sectors: irrational beliefs about its market value, over-investment, over-capacity, and more announces than services really launched (Boyer, 2002). Like other activities, e-learning has not proven yet its ability to generate high profits or to replace the old economy of learning. However, interpreting this as a failure of e-learning would however over-simplify the reality and could be seen as “throwing the baby with the bath water”. While, perhaps unsurprisingly, e-learning has not led to the radical revolution in tertiary education that was sometimes prophesised, some of its forms are already pervasive in tertiary education and have already led to a quiet revolution. Its modesty should not lead to overlook it. This section gives a overiew of the limited evidence we have about the adoption of e-learning in tertiary education. E-learning adoption The radical innovation view was that fully online learning would progressively supersede traditional face-to-face learning and represent a competitive threat for traditional tertiary educational institutions. To some extent, this belief has been a reason for the creation of new ventures and for established institutions to enter this new market: early adopters could indeed possibly gain a brand name and a serious competitive advantage in the new market. The reality is that, while sometimes successfully experimented, fully online learning has remained a marginal form of e-learning and often not even the ultimate goal or rationale for e-learning adoption. However, this does not mean that e-learning in other forms has not gained significant ground over the past decade in tertiary education: there is indeed some evidence of a noticeable growth of e-learning adoption both on demand and supply sides. 6 One must bear in mind that e-learning encompasses a wide range of activities. Following the terminology used in the CERI survey (OECD, 2005), we distinguish between different levels of online learning adoption as follows, from the less to the most intensive form of e-learning: None or trivial online presence; Web supplemented: the Web is used but not for key “active” elements of the programme (e.g. course outline and lecture notes online, use of email, links to external online resources) without any reduction in classroom time; Web dependent: Students are required to use the Internet for key “active” elements of the programme—e.g. online discussions, assessment, online project/ collaborative work—but without significant reduction in classroom time. Mixed mode: Students are required to participate in online activities, e.g. online discussions, assessment, online project/collaborative work, as part of course work, which replace part of face-to-face teaching/learning. Significant campus attendance remains. Fully online: the vast bulk of the programme is delivered online with typically no (or not significant) campus attendance or through “learning objects”. What do we know about the major trends in the adoption of e-learning by institutions and students? First, e-learning has grown steadily in the last decade, at a relatively rapid pace, but from a very low starting point—and for some activities: from scratch. The lack of comprehensive data renders these trends difficult to document, but existing surveys all point to the same direction of an increasing activity/supply. A significant share of tertiary education institutions have developed some e-learning activities and strategies and believe in the critical importance of e-learning for their long term strategy. The 2003 Sloan Survey of Online Learning based on a sample of 1 000 US institutions shows that only 19% of US institutions have no advanced elearning activities – that is web dependent, mixed mode or fully online courses (Allen and Seman, 2003). The remainding 81% offer at least one course based on those advanced elearning activities. Second, this growth of e-learning under all its forms should continue in the near future. There is indeed a converging evidence that tertiary education institutions consider as part of their future development strategy. In the Sloan survey, less than 20% of the US tertiary education institutions considered online education as not critical to their long term strategy. Similarly, data from the first international survey by the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) revealed that of the 42 UK institutions that responded (out of a total population of ca.106), 62% had developed or were developing an online learning strategy and most had done so since 2000 (OBHE, 2002). The second survey undertaken in 2004, 79% of the 122 universities from the Commonwealth countries responding to the survey had an institutionwide “online learning” strategy as such or integrated into other strategies (46%) or under development (33%). Only 9% of these institutions had no e-learning strategy in place or under 7 development in 20041. While these figures may reflect some self-selection in the respondents, they unambiguously show a significant adoption or willingness to adopt some form of elearning in the coming future. Although reflecting different levels of adoption of e-learning, all post-secondary institutions participating in the CERI survey on e-learning point to the same direction and report plans to increase their level of online delivery or to maintain their already high levels (OECD, 2005). Third, virtual universities are not likely to become the paradigm of tertiary education institutions. While it will most likely continue to grow, especially in distance institutions (see below), no evidence point towards a predominance of this form of e-learning in the near future in tertiary education. While the mixed mode of learning blending online and on-campus courses now clearly appears as a better candidate, institutions head towards the simultaneous offer of a variety of learning models. For understandable reasons, only few campus-based institutions (that is the bulk of post-secondary institutions) seem to aim at delivering a large share of their courses fully online or at becoming virtual. While some institutions participating in the CERI survey are at the avant-garde of e-learning, no campus-based institution predicted to deliver more than 10% of its total programmes fully online within three years (OECD, 2005). In the US, rather than offering only fully online courses (16%) or only mixed mode courses (10%), most institutions offer both fully online and blended courses; moreover, the majority (67%) of academic leaders believe that mixed mode and web dependent courses hold more promise than fully online, against only 14% having the opposite view (Allen and Seaman, 2003). This clearly reflects what we know about the main rationales for undertaking e-learning. The OBHE surveys show that on-campus enhancement of teaching and learning (1st) and improved flexibility of delivery for on-campus students (2nd) are the two key rationales in institutional strategies of e-learning. Only 10% of the institutions considered the enhancement of distance learning as more important than on-campus enhancement. Interestingly, the level of importance granted to distance or fully online learning decreased between 2002 and 2004 among returning respondents. Distance or fully online learning remains the fifth most important rationale though (OBHE, 2002, p. 4). Finally, while a generalisation of the fully online model is not probable for tertiary education overall, at least in the medium run, this does not mean that fully online activities are not growing rapidly nor that the fully online learning model gains ground at distance education institutions (Bates, 1995). To our knowledge, no data on fully online enrolments are available for other countries than the United States. According to the 2003 Sloan survey, more than 1.6 million students (i.e. 11% of all US tertiary-level students) took at least one fully online course during the Fall 2002 and about one third of them, that is 578 000 students, took all their courses online. For example, the University of Phoenix, the largest university in the United States in terms of enrolments, has for example 60 000 of its 140 000 students online. The enrolments of fully online students in the United States were forecasted to increase by about 20% between 2002 and 2003, to 1.9 million students—a projection that proved to be accurate according to the 2004 Sloan survey (Allen and Seaman, 2003, 2004). This growth rate, which is projected estimated at 25% for 2005 is much higher than the growth rate of total tertiary enrolments in the United States. From a low starting point, fully online learning is growing at a rapid pace, even if it is merely as a complement to face-to-face or mixed mode learning. Moreover, fully online learning is clearly very important for distance institutions. In the CERI survey, the institutions willing to embrace fully online learning to the greatest extent were all virtual/distance learning only institutions (or branches) (OECD, 2005). 1 Some institutions had indeed reported no institution-wide strategy but some strategies developed by departments or faculties, or other strategies related to e-learning. 8 In conclusion, e-learning seems to live up to its promises in terms of flexibility and possibly access. It is a growing activity that has for example significantly widened the participation in tertiary education of foreign students (OECD, 2004). Does e-learning improve the quality of tertiary education? The real impact of e-learning on the quality of education is difficult to measure. E-learning largely embodies two promises: improving education thanks to improved learning and teaching facilities; inventing and sharing new ways of learning thanks to ICTs, that is a new specific pedagogic techniques. While the first promise is by and large becoming a reality, at least in OECD countries, the second appears further from reach. Viewed mainly as an enhancement of on-campus education, and thus matching the reality depicted in the previous section, there is some evidence that e-learning has improved the quality of the educational experience on both faculty and students sides (not to mention enhancement of administrative management). All institutions participating in the CERI survey reported a “positive impact” of greater use of e-learning in all its forms on teaching and learning. The quality of education (with or without e-learning) is very difficult to measure, not the least because learning depends on students’ motivation, abilities and other conditions (e.g. family, social, economic, health backgrounds) as much as on the quality of teaching. However, the reasons explaining this positive impact on quality largely lives up to the promises of e-learning to offer more flexibility of access to learners, better facilities and resources to study, and new opportunities thanks to the relaxation of space and time constraints. Basically, they do not correspond to a significant change in class pedagogy, but to a change in the overall learning experience. According to the institutions, the main drivers or components of this positive impact come from: facilitated access to international faculty/peers, e.g. with the possibility of online lectures or joint classes with remote students; flexible access to materials and other resources, allowing students to revise a particular aspect of a class, giving more access flexibility to part-time students, or giving remote and easy access to the library materials; enhancement of face-to-face sessions, as the availability of archived lectures online frees up faculty time to focus on difficult points and application and because the introduction of e-learning has sometimes led to a debate on pedagogy; improved communication between faculty and students and increase of peer learning; This “positive impact” on the overall learning experience is, alone, a significant achievement of e-learning, even though it has not radically transformed the learning and teaching processes. The quality of fully online learning is a more controversial question, possibly because online learning was once viewed as possibly become of higher quality than on-campus education (possibly including e-learning as already mentioned). Comparing the quality (or the beliefs about the quality) of fully online learning against traditional distance learning, traditional face-to-face learning or other mixed modes of e-learning might not yield the same results: fully online learning is indeed more readily comparable to distance learning than to oncampus education. While institutions having adopted e-learning have generally a positive 9 view of its possible impact on quality, there is little convincing evidence about the superior or inferior quality of fully online learning compared to other modes of tertiary education. Another question is whether fully online learning has entailed innovation in pedagogy or just replicated with other means the face-to-face experience. As noted above, ICTs could indeed entail pedagogic innovations and help create a community of knowledge among faculty, students and learning object developers that would codify and capitalise over successful innovation in pedagogy. At this stage, there is no evidence that e-learning has yielded any radical pedagogic innovation. The most successful fully online courses generally replicate virtually the classroom experience via a mix of synchronous classes and asynchronous exchanges. Arguably, they have not represented a dramatic pedagogical change. We will see below that in spite of worthwhile experiments, learning objects and open educational resources are still in their infancy. They hold promises for educational innovation though. The cost of e-learning Has e-learning lived up its promises in terms of cost-efficiency? Here again, not if one looks at the most radical promises: as noted above, virtual universities have not replaced brick and mortars and saved the cost of expensive building investments and maintenance; digital libraries have supplemented rather than replaced physical ones; the codification and standardisation of teaching in a way that would allow less faculty or less qualified academics has not become the norm, nor have new online learning objects been invented to replace faculty altogether; finally, it has become clear that there was no once-for-all ICT investments and that the maintenance and upgrading costs of ICT facilities were actually important, contrary to the marginal cost of then replicating and diffusing information. Moreover, cost-efficiency has for many universities been a secondary goal compared to the challenge of developing innovative and high quality e-learning courses at many tertiary education institutions. Although the ranking of cost-efficiency has increased between 2002 and 2004 by 16%, 37% of respondents considered “cutting teaching costs long-term” as a key rationale in the OBHE survey (OBHE, 2004)—a small percentage compared to the two key rationales (over 90% of responses). Again, most universities consider e-learning materials and courses as a supplement to traditional class-room or lecture activities rather than a substitute. The predominance of web dependent and mixed modes of e-learning makes the assessment of the costs and benefits of e-learning investments more difficult to evaluate as they become part of the on-campus experience. It is striking that the institutions participating in the CERI survey on e-learning had no systematic data on their e-learning costs (OECD, 2005). In this context, and after the burst of the dot.com economy bubble that put out of business many elearning operations (many never really started their operations though), identifying sustainable cost-efficient models for e-learning investments in tertiary education has become critical. There are examples of cost-efficient models “outside” the traditional colleges and universities though. Virtual tertiary education institutions as e.g. the Catalonia Virtual University have a cost advantage as they are developing e-learning material from scratch and not “building onto” a physical camp. The Open University in the UK which is gradually moving from a traditional distance learning courses using books, video cassettes, and CD-ROMs to online courses has reported that their costs per student are one third of the average cost for similar on-campus programmes in the UK. Fixed capital costs are lower and it is easier to align 10 staffing structures to e-learning processes than at “traditional” universities. The e-learning activities of Phoenix University, which is a private for-profit university mainly for adult students, is also seen as cost-effective. Its business model is based on “standardised teaching”, relatively small on-line class size, and use of proven low-tech e-learning technologies (inducing lower costs than more sophisticated technologies). Much of the faculty staff at Phoenix University is often hired part time and having jobs at other tertiary education institutions, which often implies that staff development costs are lower at Phoenix University than other tertiary education institutions. E-learning investments in tertiary education can be cost-effective, but it depends on the business model, the profile and number of students and topics (cost-effectiveness has been demonstrated in some cases in large undergraduate science classes (Harley, 2003), and initial development costs. The calculations also depend on whether student opportunity costs are taken into account. The initial costs for e-learning development are often high (e.g. infrastructure, creating course material from scratch, experimentation, new kind of staff/units, immature technologies, etc.). In order to ensure that e-learning investments are cost efficient, e-learning activities may need to substitute parts of the on-campus teaching activities (rather than duplication). Educational innovations, like learning objects, could for example allow supporting the re-use and sharing of e-learning materials. Although data is lacking on cost-efficiency, at this stage there is little evidence that e-learning has led to more cost efficiency in tertiary education. Failures have been more numerous than success stories, although the latter document the possible sustainability of e-learning. The adoption of ICTs for administrating tertiary education institutions has probably been the main source of cost efficiency in the tertiary sector, like in other economic sectors. Conclusion: the e-learning adoption cycles So, has e-learning lived up to its promises? This is probably true as far as it holds promises for incremental improvement, including an increased access and quality of the learning experience—a kind of change whose importance should not be underestimated. As for radical innovation, the answer is rather: not yet. So far, e-learning has induced a quiet rather than a radical revolution of tertiary education. Perhaps e-learning will follow the same development path in tertiary education as other innovations that first begin with experiments, then expand to a group of early adopters before becoming commonplace. Zemsky and Massy (2004) have proposed a possible “e-learning innovation’s S-curve” divided into four distinctive but often overlapping adoption cycles that help understand the current development of e-learning, and, possibly, its future challenges. The cycles include: 1) Enhancements to traditional course/program configurations, which inject new materials into teaching and learning processes without changing the basic mode of instruction. Examples include e-mail, student access to information on the Internet, and the use of multimedia (e.g. PowerPoint) and simple simulations; 2) Use of course management systems, which enable faculty and students to interact more efficiently (e.g. Blackboard or WebCT). They provide better communication with and among students, quick access to course materials, and support for administrating and grading examinations; 11 3) Imported course objects, which enable the faculty to embed a richer variety of materials into their courses than is possible with traditional “do it yourself” learning devices. Examples range from compressed video presentations to complex interactive simulations including the increased use of “learning objects”2; 4) New course/program configurations, which result when faculty and their institutions reengineer teaching and learning activities to take full advantage of new ICTs. The new configurations focus on active learning and combine face-to-face, virtual, synchronous, and asynchronous interaction and learning in novel ways. They also require faculty and students to adopt new roles – with each other and with the technology and support staff. The overview of current e-learning adoption shows that most tertiary education institutions in OECD countries can largely be located in cycles one and/or two. These first two cycles have largely built upon and reinforced one another. However, they have not fundamentally changed the way teaching and learning is pursued at the large majority of institutions. Their momentum has not automatically transferred to either increasing use and dissemination of learning objects or to the use of new course/program configurations (e-learning cycles three and four). Cycles 3 and 4 correspond to changes remodelling more radically teaching and learning. While some experimentations underway give us some idea of where they could head, they are still in their infancy. The third cycle corresponds to the creation of “learning objects” that can potentially offer an efficient approach to the development of e-learning materials (i.e. reduced faculty time, lower cost, higher quality materials), although many issues remain (e.g. copyright, lack of incentives for faculty to create, the range of actors in and ‘location’ of the creative process, lack of standardisation and interoperability of e-learning software). The learning objects model implies material/course development that departs from the “craft-model” where the individual professor is responsible for the majority of work. Instead it is a model where the course is assembled largely by or from third-party material. Besides the technical and organisational challenges of developing learning objects, there are also considerable pedagogical challenges using them. Some argue that learning is so contextually based that the breaking up of the learning experience into defined objects is destructive for the learning process. Evidence from the Open Learning Initiative at the Carnegie Mellon University suggests that effective e-learning courses are often facilitated by having a ‘theme’ that runs throughout the course, which might be difficult to obtain with the notion of decontextualised learning objects (Smith and Thille, 2004). Therefore, much more research and development is needed to ensure pedagogical effectiveness of the learning objects model. For faculty members to rely on others for their material will also need a cultural change as it would probably often be considered today as demonstrating “inferiority”. Wide use of learning objects in tertiary education will therefore only occur if major changes in working habits and attitudes of faculty are possible. 2 « Learning objects » has become a widely used term to describe a model of materials development that manipulates and combines/re-combines discrete ‘chunks’ of material designed to be re-used and re-purposed for different needs. There is however not a fixed definition of what a learning object is, and an object may range from a single chart to an entire course. 12 The development of learning objects is very much in its initial phase. This is illustrated by the use of the public available learning objects repositories as e.g. MERLOT (Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching). The basic idea behind the MERLOT repository was to create a readily available, low-cost, web-based service to which experimenters could post their learning objects and from which interested practitioners could rate and download objects for use in their courses. While there has been a tremendous growth in the number of learning objects made available by MERLOT, there has been very little interest to use what other colleagues had made available and consequently little effort in terms of rating others’ learning objects. This can however be seen as the first steps towards the construction of knowledge communities in education. Despite the premature stage of learning objects and the large number of obstacles to overcome, some standard form of learning objects will probably emerge and gain importance in the development of e-learning in tertiary education as well as in other education sectors. Very few institutions have reached the fourth e-learning adoption cycle at an institution wide scale. There are however institutions which are clearly experimenting with new ways of using ICTs that change the traditional organisation and pedagogy of tertiary education. One such example is the previously mentioned Open Learning Initiative at the Carnegie Mellon University. The use of cognitive and learning sciences to produce high quality e-learning courses into online learning practices is at the core of this initiative (Smith and Thille, 2004). As there is no generic e-learning pedagogy, the aim is to design as “cognitive informed” elearning courses as possible. The establishment and implementation procedures for routine evaluation of the courses and the use of formative assessment for corrections and iterative improvements are part of the e-learning course development. The development of the elearning courses often rely on teamwork including faculty from multiple disciplines, web designers, cognitive scientists, project managers, learning designers, and evaluators. The key question for any project like the Open Learning Initiative attempting a combination of open access to free content, and a fee-for-service model for students using the courses in a degree granting setting is its sustainability. This initiative could not have been realised without significant voluntary contributions from private foundations and a major research grant from the National Science Foundation to start the Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center. The next section will address the challenges for the adoption of these third and fourth adoption cycles. III. Challenges for the further development of e-learning in tertiary education: what sustainable innovation model? The aim of this final section is to identify and reflect on some of the key issues that would need to be considered in a systematic way for e-learning to develop further and become a deeper driver of innovation in tertiary education. If the vast majority of colleges and universities are to embrace the third and fourth e-learning adoption cycles, a sustainable innovation and investment model will have to be developed. A first challenge lies indeed in the development of sustainable e-learning innovation models which go beyond using elearning as an add-on to traditional forms of teaching and learning in tertiary education but rather invent new, useful and better pedagogic innovations partly substituting traditional face13 to-face teaching. This will require a broad willingness of these institutions to search for new combinations of input of faculty, facilities and technology and new ways of organising their teaching activities. A second challenge lies in the development of a realistic model for investment in e-learning that would stimulate the participation of faculty and other stakeholders and be financially sustainable, which is not straightforward given that there is little systematic knowledge on the real costs and benefits of e-learning investments in tertiary education. However, like for ICT investments in other sectors, the cost-effectiveness of elearning investments will depend on whether new organisational and knowledge management practices are adopted. It might indeed be more difficult to provide the “softer” social, organisational and legal changes in tertiary education than the technological infrastructures necessary to fully embrace the advantages of e-learning. This section emphasises partnerships and networks as a possible way forward for further investment, product development and innovation diffusion in e-learning. There are many examples where tertiary education institutions seek to share the costs of e-learning development through partnerships and networking. Partnership and network building are also useful for having access to new knowledge, to learn from others experience and exchange information about the latest developments in e-learning and they can involve many different organisations as e.g. traditional colleges and universities, virtual universities, libraries, forprofit ICT and training companies from different sectors etc. These activities can range from sharing material, joint technology and software development, joint research and development, joint marketing, joint training, connectivity, etc. and can be sub-national, national and international (OECD, 2004b; Cunningham and al., 2000). After showing the importance (and challenges) for universities to engaging their faculty in e-learning, we will turn to an innovative practice exemplifying the potential power of partnerships and networks: Open Educational Resources (OER). They will indeed most likely have significant implications for the way e-learning activities will develop over the coming years in tertiary education. Engaging universities and faculty in e-learning In most OECD countries the question is no longer whether or not tertiary education institutions should invest in e-learning. Because of the competition between institutions and student demand for easy access to courseware material and flexible learning environments, most tertiary education institutions willing to deliver quality teaching are bound to invest in elearning. As we have seen, the large majority of institutions are now embracing e-learning adoption cycles one and two, which are basically about providing the students with better access to learning and course material and facilitating the electronic communication between students and teachers. Again, only very few institutions and faculty are however systematically exploring and producing re-usable learning material and objects (third cycle) or have taken full advantage of new ICTs with focus on active learning that combines face-toface, virtual, synchronous, and asynchronous interaction and learning in novel ways (fourth cycle). The latter approach would require faculty and students to adopt new roles – with each other and with the technology and support staff. While ICTs offer powerful new instruments for innovation, tertiary education institutions are generally decentralised institutions where individual faculty often has the sole responsibility for teaching courses and delivering course material. Adoption of the third and especially the fourth e-learning cycle would imply changing to more collaborative ways of organising and producing teaching material. Faculty members would in many cases have to collaborate with a whole range of new staff as e.g. course managers, web designers, instructional/pedagogical 14 designers, cognitive scientist etc. to produce course material. This could lead to resistance from “traditional” faculty arguing that current teaching practices have proved its value for centuries and there is no need to change them to new pedagogical and teaching methods, which have hardly proven their efficiency yet. Moreover, promotion of faculty and funding allocations in universities are often linked to research activities rather than teaching activities, often seen as less prestigious. Faculty members have therefore often relatively few incentives to invest their time in e-learning activities. The adoption of new ways of teaching and learning at tertiary education institutions through ICTs can therefore create organisational conflicts and tensions. New organisational innovations, new knowledge management practices, and more team working are therefore necessary conditions for tertiary education institutions to be able to move to e-learning adoption cycles three and four. The CERI study on e-learning case studies in post-secondary education has identified a number of lessons learnt by institutions that are in the forefront of e-learning development (OECD, 2005): More strategic e-learning planning at the institutional or faculty level and to tie this to the overall goals of the institution is needed; A paradigm shift in the way academics think of university teaching would be necessary, e.g. a shift away from ‘scepticism about the use of technologies in education’ and ‘teacher-centred culture’ towards ‘a role as a facilitator of learning processes’, ‘team worker’, and ‘learner-centred culture’; Targeted e-learning training relevant for the faculty’s teaching programme as well as ownership of the development process of new e-learning material by academics is also necessary. There is no one-best-way or trajectory for e-learning development at tertiary education institutions. But it might prove more difficult to provide the “softer” social, organisational and legal changes in tertiary education than provide the technological infrastructures necessary to fully embrace the advantages of e-learning (David, 2004). It will depend on a whole range of factors not necessarily related to the development of e-learning including: Changes in the funding of tertiary education and in particular e-learning funding; Student demography; Regulatory and legal frameworks; Competition between traditional tertiary education institution themselves and with new private providers; Internationalisation including the possibility of servicing foreign students living abroad; and not the least to the extent to which students will want to use the new opportunities for new and flexible ways of learning. Many tertiary education students would possibly prefer to have some kind of “mixed model” learning choice involving a whole range of different learning opportunities and forms combining face-to-face, virtual, synchronous, and asynchronous interaction and learning. A possible way forward: Open Educational Resources Open Educational Resources appear as a potentially innovative practice that gives a good example of the current opportunities and challenges offered by ICTs in order to trigger radical pedagogic innovations. Digitalisation and the potential for instant, low-cost global 15 communication have opened tremendous new opportunities for the dissemination and use of learning material. This has spurred an increased number of freely accessible OER initiatives on the Internet including 1) open courseware3; 2) open software tools4 (e.g. learning management systems); 3) open material for capacity building of faculty staff 5; 4) repositories of learning objects6; 5) and free educational e-learning courses. At the same time, there are now more realistic expectations of the commercial e-learning opportunities in tertiary education. The OER initiatives are a relatively new phenomenon in tertiary education largely made possible by the use of ICTs. The open sharing of one’s educational resources implies that knowledge is made freely available on non-commercial terms sometimes in the framework of users and doers communities. In such communities the innovation impact is greater when it is shared: the users are freely revealing their knowledge and, thus work cooperatively. These communities are often not able to extract economic revenues directly from the knowledge and information goods they are producing and the “sharing” of these good are not steered by market mechanisms. Instead they have specific reward systems often designed to give some kind of credit to inventors without exclusivity rights. In the case of open science, the reward system is collegial reputation, where there is a need to be identified and recognised as “the one who discovered” which gives incentives for the faculty to publish new knowledge quickly and completely (Dasgupta and David, 1994). The main motivation or incentive for people to make OER material available freely is that the material might be adopted by others and maybe even is modified and improved. Reputation is therefore also a key motivation factor in “OER communities”. Being part of such a user community gives access to knowledge and information from others but it also implies that one has a “moral” obligation to share one’s own information. Inventors of OER can benefit from increased “free distribution” or from distribution at very low marginal costs. A direct result of free revealing is to increase the diffusion of that innovation relative to conditions in which it is licensed or kept secret. If an innovation is widely used it would initiate and develop standards which could be advantageously used even by rivals. The Sakai project has, for example, an interest in making their open software tools available for many colleges and universities and have therefore set a relatively low entry amount for additional colleges and universities wishing to have access to the software tools that they are developing. The financial sustainability of OER initiatives is a key issue. Many initiatives are sponsored by private foundations, public funding or paid by the institutions themselves. In general, the social value of knowledge and information tools increases to the degree that they can be shared with and used by others. The individual faculty member or institution providing social value might not be able to sustain the costs of providing OER material freely on the Internet in the long term. It is therefore important to find revenues to sustain these activities. It might e.g. be possible to charge and to take copyrights on part of the knowledge and information 3 A well-known example is the MIT Open Courseware project which is making the course material taught at MIT freely available on the Internet. 4 An example is the so-called Sakai project in United States where the University of Michigan, Indiana University, MIT, Stanford University and the UPortal Consortium are joining forces to integrate and synchronise their educational software into a pre-integrated collection of open software tools. 5 The Bertelsmann and the Heinz Nixdorf foundations have sponsored the e@teaching initiative aiming at advising faculty in Germany in the use of open e-learning material. 6 E.g. the MERLOT learning objects repository. 16 activities springing out of the OER initiatives. Finding better ways of sharing and re-using elearning material (see the previous mentioned discussion on learning objects) might also trigger off revenues. It is also important to find new ways for the users of OER to be “advised” of the quality of the learning material stored in open repositories. The wealth of learning material is enormous on the Internet and if there is little or no guidance of the quality of the learning material, users will be tempted to look for existing brands and known quality. There is no golden standard or method of identifying quality of learning material in tertiary education on the Internet as is the case with quality identification within tertiary education as a whole. The intentions behind the MERLOT learning object repository was to have the user community rating the quality and usability of the learning objects made freely available. In reality very few users have taken the time and effort to evaluate other learning objects. There is little doubt that the generic lack of a review process or quality assessment system is a serious issue and is hindering increased uptake and usage of OER. User commentary, branding, peer reviews or user communities evaluating the quality and usefulness of the OER might be possible ways forward. Another important challenge is to adapt “global OER initiatives” to local needs and to provide a dialogue between the doers and users of the OER. Lack of cultural and language sensitivities might be an important barrier to the receptiveness of the users. Training initiatives for users to be able to apply course material and/or software might be a way to reach potential users. Also important will be the choice (using widely agreed standards), maintenance, and user access to the technologies chosen for the OER. There is a huge task in better understanding the users of OER. Only very few and hardly conclusive surveys on the users of OER are available7. There is a high need to better understand the demand and the users of OER. A key issue is who owns the e-learning material developed by faculty. Is it the faculty or the institution? In many countries including the United States, the longstanding practice in tertiary education has been to allow the faculty the ownership of their lecture notes and classroom presentations. This practice has not always automatically been applied to e-learning course material. Some universities have adopted policies that share revenues from e-learning material produced by faculty. Other universities have adopted policies that apply institutional ownership only when the use of university resources is substantial (American Council of Education and EDUCAUSE, 2003). In any case, institutions and faculty groups must strive to maintain a policy that provides for the university’s use of materials and simultaneously fosters and supports faculty innovation. It will be interesting to analyse how proprietary versus open e-learning initiatives will develop over the coming years in tertiary education. Their respective development will depend upon: 7 How the copyright practices and rules for e-learning material will develop at tertiary education institutions; The extent to which innovative user communities will be built around OER initiatives; The extent to which learning objects models will prove to be successful; One exception is the user survey of MIT’s Open Courseware. 17 The extent to which new organisational forms in teaching and learning at tertiary education institutions will crystallise; The demand for free versus “fee-paid” e-learning material; The role of private companies in promoting e-learning investments etc. It is however likely that proprietary e-learning initiatives will not dominate or take over open e-learning initiatives or vice versa. The two approaches will more likely develop side by side sometimes in competition but also being able to mutually reinforce each other through new innovations and market opportunities. Conclusion There are many critical issues surrounding e-learning in tertiary education that need to be addressed in order to fulfil objectives such as widening access to educational opportunities; enhancing the quality of learning; and reducing the cost of tertiary education. E-learning is, in all its forms, a relatively recent phenomenon in tertiary education that has largely not radically transformed teaching and learning practices nor significantly changed the access, costs, and quality of tertiary education. As we have shown, e-learning has grown at a rapid pace and has enhanced the overall learning and teaching experience. While it has not lived up to its most ambitious promises to stem radical innovations in the pedagogic and organisational models of the tertiary education, it has quietly enhanced and improved the traditional learning processes. Most institutions are thus currently in the early phase of e-learning adoption, characterised by important enhancements of the learning process but no radical change in learning and teaching. Like other innovations, they might however live up to their more radical promises in the future and really lead to the inventions of new ways of teaching, learning and interacting within a knowledge community constituted of learners and teachers. In order to head towards these advances innovation cycles, a sustainable innovation and investment model will have to be developed. While a first challenge will be technical, this will also require a broad willingness of tertiary education institutions to search for new combinations of input of faculty, facilities and technology and new ways of organising their teaching activities. Like for ICT investments in other sectors, the cost-effectiveness of e-learning investments will depend on whether new organisational and knowledge management practices are adopted. Experiments are already underway that make us aware of these challenges, but also of the opportunities and lasting promises of e-learning in tertiary education. References Allen, I. E. and Seaman, J. (2003), Sizing the opportunity. The Quality and Extent of Online Education in the United States, 2002 and 2003, The Sloan Consortium. American Council on Education and EDUCAUSE (2003), Distributed Education: Challenges, Choices and a New Environment, Washington DC. Atkins, D.E., Droegemeier, K.K., Feldman, S.I., Garcia-Molina, H., Klein, M.L., Messerschmitt, D.G., Messina, P., Ostriker, J.P., Wright, M.H., Final Report of the NSF Blue 18 Ribbon Advisory Panel on Cyberinfrastructure, http://www.cise.nsf.gov/sci/reports/toc.cfm. February 2003. available at Bates, A. W. (1995), Technology, e-learning and Distance Education, Routledge, London/New York. Boyer, R. (2002), La croissance, début de siècle. De l’octet au gène, Albin Michel, Paris; English translation: The Future of Economic Growth: As New Becomes Old, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 2004. Cunningham, S., Ryan, Y., Stedman, L., Tapsall, S., Bagdon, S., Flew, T., Coaldrake, P. (2000), The Business of Borderless Education, Australian Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs, Canberra. Dasgupta, P. and P.A. David (1994), “Towards a New Economics of Science”, Research Policy, 23(5). David, P.A (2004), Toward a Cyberinfrastructure from Enhanced Scientific Collaboration: Providing its ‘Soft’ Foundations May be the Hardest Threat, Oxford Internet Institute. Foray, D. (2004), The Economics of Knowledge, MIT Press, Cambridge, USA. Harley, D. (2003), Costs, Culture, and Complexity: An Analysis of Technology Enhancements in a Large Lecture Course of UC Berkeley, Center for Studies in Higher Education. Paper CSHE3-03, Berkeley University. Hutchins, E. (1995), Cognition in the Wild, MIT Press, Cambridge, USA. Nelson, R. (2000), “Knowledge and Innovation Systems”, in OECD, Knowledge Management in the Learning Society, Paris. Observatory for Borderless Higher Education (2002), Online Learning in Commonwealth Universities – Results from the Observatory 2002 Survey, London. OECD (2003), New Challenges for Educational Research, OECD, Paris. OECD (2004a), Innovation in the Knowledge Economy – Implications for Education and Learning, Paris. OECD (2004b), Internationalisation and Trade in Higher Education. Opportunities and Challenges, Paris. OECD (2005 forthcoming), E-learning Case Studies in Post-Secondary Education, Paris. Smith, J. M. and C. Thille (2004), The Open Learning Initiative – Cognitively Informed elearning, The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education, London. World Bank (2003), Constructing Knowledge Societies: New Challenges for Tertiary Education, The World Bank, Washington D.C. 19 Zemsky, R. and W.F. Massy (2004), Thwarted Innovation – What Happened to e-learning and Why, The Learning Alliance, Pennsylvania University. 20