WinningSearchIssuesS.. - First District Appellate Project

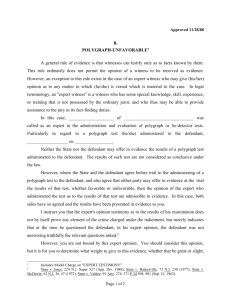

advertisement