Support children to build and maintain trusting relationships

advertisement

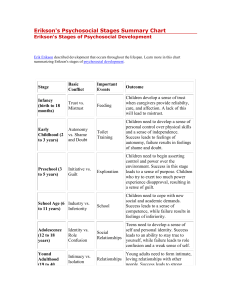

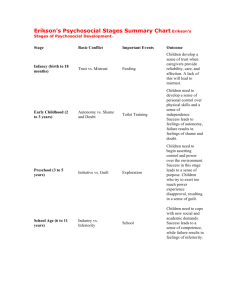

CHCFC503A: Foster social development in early childhood Support children to build and maintain trusting relationships Contents Support children to build and maintain trusting relationships 3 Theoretical perspectives 3 Trust versus mistrust 3 Autonomy versus shame and doubt 5 Initiative versus guilt 6 Industry versus inferiority 7 Influences on social development 8 Listen attentively and show children their views are valued and acknowledged How to show children that you care for and value them 10 Acknowledge and support children’s preferences for particular adults and peers 12 Help children to understand and accept responsibility for their actions 13 Aggression 2 10 13 Encourage children to express and manage feelings appropriately 14 Support children’s various levels of interaction and participation with others during play 15 Joining groups and initiating interactions with peers 15 Social play 15 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 Support children to build and maintain trusting relationships Theoretical perspectives Note: This first section on theoretical perspectives is the same as the text in Topic 1 of CHCFC504A Encourage children’s independence and autonomy. It is included in both units as it covers the theoretical aspects in both and demonstrates the close links between social, emotional and psychological development. In this section we will be looking very closely at the work of a theorist called Erik Erikson. You may have come across some information on him in other learning topics. Here we will be looking very specifically at the first four stages that Erikson describes. Erikson’s work is very closely linked to children developing control of their lives and gradual independence. Erikson (1902–1994) built upon Sigmund Freud’s work. He identified eight separate stages across the lifespan. He believed that in each stage we face a crisis that needs to be resolved in order for us to develop socially and emotionally. Each stage can be resolved in a positive or a negative way, though in reality the resolution will be somewhere between these two extremes. The outcome of the stage is determined by our environment and the caregiving strategies or experiences to which we are exposed. The stages that we will be examining are: • • • • trust versus mistrust: 0–18 months autonomy versus shame and doubt: 18 months–3 years initiative versus guilt: 3–5 years industry versus inferiority: 5–12 years Trust versus mistrust Infancy correlates with Erikson’s first stage: trust versus mistrust. In this stage the infant is beginning to interact and engage with the people they come into contact with to deal with the first crisis identified by Erikson. This crisis is to determine Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 3 whether the infant should trust the world and the people in it or mistrust the world and its people. Trust or mistrust in the world will be determined by the type of care the infant is receiving from the adults. Trust, like attachment, is built through our basic caregiving strategies. Feeding a hungry baby, cuddling and soothing a fearful baby and allowing the tired child to sleep, helps build trust. Building trust Trust Mistrust Child who explores world Fearful child Child who seeks caregiver’s attention appropriately Mistrust adults Child uses parent as secure base Open Withdrawn Trusting Not very curious Wants to be near people Doesn’t explore freely Inquisitive Activity 1 Developing trusting relationships with infants It is vital that we develop trusting relationships with the infants in our care. Without these relationships the infants will not be able to create the emotional base needed for future development. Activity 2 4 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 Autonomy versus shame and doubt In toddlerhood, the child is now moving to a new stage in their development. Erikson describes a new crisis that must be dealt with. Again, the real usefulness of this theory is in the information it gives us about the appropriate caregiving strategies that we need to employ to help each child reach their full potential. In this toddler stage, Erikson describes the crisis as being one of autonomy versus shame and doubt. During this stage the toddler will learn that they are an autonomous, independent person who has control in their world or they will learn that making independent decisions is something to be ashamed of. This is often a challenging stage for many adults. Our first word is often ‘NO’. Being told ‘no’ all the time leads to feelings of shame and doubt. We need to ensure that we give toddlers the opportunity to make limited decisions. We will discuss decision making in more detail later. Outcomes of autonomy Toddlers who are encouraged to be autonomous and who receive appropriate caregiving strategies in this stage will: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • have a positive self-concept be eager to try new skills be independent be motivated to do things for self have a good relationship with the primary caregiver demonstrate self-help and self-care skills be confident trust in others want to explore their environment and new environments gain a sense of belonging be able to express feelings appropriately be curious come to the caregiver for support and reassurance show emotions in actions make simple demands gain mastery over their bodily functions want to do things alone be able to accept help and guidance take pride in their new skills learn that failure is a learning process be more self-sufficient be more sociable need confirmation and recognition of efforts. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 5 Outcomes of shame or doubt Alternatively the child who is not allowed to explore their environment and who does not receive appropriate caregiving strategies for this stage of development will: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • doubt themselves and their capabilities often be withdrawn feel shame in the eyes of themselves and others or may be disruptive demonstrate unrealistic fears be dependant on others feel worthless and have a low self-esteem demonstrate poor social skills have negative self-concepts lack motivation or have poor motivation to complete tasks often require lots of adult assistance demonstrate a lack of willingness to explore the environment often be unsociable demonstrate lots of frustration be lacking skills in all areas be unsure and lacking confidence often lack mastery over bodily functions. Activity 3 Initiative versus guilt Erikson and the preschooler Now that the child is a preschooler, a new crisis is emerging. Erikson now tells us that the child is moving into the initiative-versus-guilt stage. In this stage the child will either gain a sense of initiative by being able to make decisions, plan activities and events and see them carried through, or a feeling of guilt as they are continually told ‘no’ or have their ideas squashed. Caregivers need to ensure they are allowing the children in their care the opportunities to make plans and see them carried through to fruition. Erikson stresses that a person’s personality emerges from the child’s interactions and experiences with significant people. Much of this interaction occurs around all the different skills that are developing during the preschool years. During the preschool stage we find that children are ready and eager to learn and achieve goals. They learn to plan and to carry out these plans. They are also 6 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 developing a sense of right and wrong. They see themselves as being able to do more things but realise there are limits – if they go beyond these limits, they will feel guilty. By four years the preschooler should be able to formulate a plan of action and carry it out. The positive outcome is a sense of initiative – the sense that one’s desires and actions are good and OK. As caregivers we need to ensure that we are helping preschoolers to focus their energies on what is allowed and directing them towards acceptable activities so that guilt is kept to a minimum. We can ensure that we are encouraging initiative by asking the children to suggest activities which could be included within the program. When they make suggestions we then need to ensure that we treat children’s ideas and suggestions seriously. It is important that we do not dismiss them with ridicule or laugh at them. If children’s ideas are unacceptable then discuss with the children alternatives which are socially acceptable. Following these simple strategies will ensure that children navigate through this stage leading to a positive outcome. The outcomes of children gaining a good sense of initiative are to: • • • • • • use their initiative constructively enjoy their increasing power become better able to cooperate be better able to accept guidance use their initiative within the limits of acceptable behaviour experience a minimum of guilt. The negative outcome of this stage is ‘guilt and shame’. Guilt and shame will occur if children are continually punished for initiating and carrying out plans. They will also experience this if their ideas are rejected out of hand or laughed at, ridiculed or ignored. These feelings of guilt lead to feelings of shame and fear and a lack of assertiveness in their behaviour. One of the dangers of this stage is that, if children are punished for initiative, they will turn their energies into being obedient and conforming in order to avoid feeling guilty. Activity 4 Industry versus inferiority Erikson and the school-aged child School-aged children between six and 12 years of age are beginning to settle down to the serious business of learning to read and write as well as the many other skills that are being developed at this stage. They are often in a routine Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 7 involving school and their peers. Erikson’s fourth stage, industry versus inferiority, is usually being demonstrated at this time. Erikson saw this stage as the time when children will begin to be industrious and work towards their future careers and lives. They will learn the skills associated with their society. Children who are reared in a positive, appropriate way will navigate through this stage with positive outcomes. They will feel good about themselves and their abilities. Children who are receiving negative messages from the people around them will feel inferior to those around them and thus will come through this stage with negative thoughts. Encourage school-aged children to feel good about themselves Activity 5 Now, let’s look briefly at some influences on social development. Influences on social development As with emotional development there are a number of influences that are going to directly impact the child’s social development and competence. Culture and ethnicity Culture and ethnicity are going to directly influence children’s social competence and development. Individual cultures have different expectations of children. In some cultures children are expected to be seen but not heard, while others value children who speak their minds and ‘have attitude’. Middle Eastern cultures often have different expectations of the girls than they do of the boys. Each of these factors and many more are going to affect the caregiver’s interactions with and understanding of the family. Caregivers need to be very aware of their values and 8 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 attitudes and ensure they are aware of the values and attitudes of the cultures of the families within their care. Family and socio-economic status (SES) The influence of the family and also the SES cannot be underestimated. Remember the quality of the caregiving and interactions within the family has the greatest impact on the child’s social competence. If children are not given the opportunity to practice their social skills or have inappropriate skills consistently demonstrated to them, they are less likely to become socially competent children. Parenting styles Three types of parenting styles have been identified by Diana Baumrind (Berk 1996). The table below summarises the parent behaviours and the outcomes or behaviours of children. Parenting style Parent behaviours Children’s outcomes Authoritative Expects appropriate maturity from children Children develop well Sets limits consistently Shows affection Children allowed to express their points of view Children participate in family decisions Authoritarian Unresponsive and rejecting when children do not obey Children are not negotiated with Children are punished for being disobedient Happy Lively Attempt and master new tasks Self-controlled Friendly and cooperative Anxious Withdrawn Unhappy React with hostility Quick to anger Openly defiant Dependant Permissive Very accepting of children Difficulty controlling impulses Little or no discipline or limits set Demanding of adults Lack of persistence. Berk (1996) Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 9 Listen attentively and show children their views are valued and acknowledged Children gain their understanding of the social world and their place in it from what they experience. If adults respond to a child frequently with warm, caring and respectful interactions, the child will build an image of themself as someone who is cared about, who has worthwhile ideas and who is interesting to others. What kind of behaviours should we use in our interactions with children that show them that we care about them and are interested in what they communicate? How to show children that you care for and value them As a sound foundation, we need to make sure of our motivation. Children are very quick to recognise when they are being patronised or when communication is not genuine. In everything you do and say, you need to show children that you enjoy being in their company and are interested in their communications. Making time to listen and respond to each child is more important than almost any other aspect of our work with children. Some of the ways you can ensure that your interactions with children are frequent, caring and respectful are outlined below. Spend time with each child Make time to spend with each child in both planned and spontaneous situations. If you are just beginning to work with children you may need to structure this into your planning until you become more skilled in time management. Over time, you will develop your abilities until frequent, quality interactions with individual children become a natural part of the flow of every day. Do not forget that this applies to all children, including babies who cannot yet talk, children who are not able to communicate freely through speech and children with a first language other than English. 10 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 Communicate interest and respect Use your body language to show your interest and respect. Non-verbal communication, for example personal space, facial expressions and body posture, gives the child a very clear indication of your involvement in the interaction. Lean into the child, kneel or crouch down so your face and eye level are similar, use appropriate facial expressions and encouragement to show you are engaged in what the child is communicating. Follow up on interactions Refer to the interaction at another time. Provide appropriate resources that show the child you have taken note of their interests and share appropriate communications with others. For example, tell other children about your conversation during a group time. How we respond to the children will affect how they interact with the rest of the environment. If we show interest and are actively involved in experiences and activities, then the children will follow our lead. There are several ways that we can show children that their views are valued and acknowledged. We can: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • listen to what they have to say make eye contact when you or they are talking (please remember that in some cultures this may not be appropriate) speak warmly and enthusiastically value their work by putting it on display encourage and guide children to recognise and solve problems in appropriate ways allow children to play an active role in setting up and maintaining the environment be aware of ensuring that activities are child-centred, rather than carerdirected be positive in our language—both verbal and non-verbal recognise and accept children’s emotions follow through on children’s requests and interests provide advice and suggestions, but allow them the final decision treat them with warmth and respect treat other staff members with respect value the skills that others can bring to a service—staff, parents, students, volunteers and children. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 11 Acknowledge and support children’s preferences for particular adults and peers We all have favourites—this is only natural. Children will prefer particular carers and we should acknowledge and support their preferences. We should not allow feelings of envy or jealousy taint our interactions with children. Children will model themselves on our behaviour and so we should treat all children with the same respect and fairness. Naturally we will have favourites among the children, but we must be careful not to treat these favourites any different to the other children. Children will also have favourites amongst themselves. Again we should acknowledge and support this. However we should look out for those children who are not ‘preferred’ and appear not to have any particular friends and try to work out why this is so and if the child seems distressed about this, try subtly to do something to remedy this. 12 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 Help children to understand and accept responsibility for their actions Aggression Children are aggressive for a variety of individual and environmental reasons. It is essential that workers are sensitive to any emergence of aggressive behaviours within a group or individual. It is often an alarm bell that the environment and the care giving practices within the service are not inclusive or supportive of social skill development appropriate to the children's age or stage of development. Aggression is seen in many different forms and may be either verbal or physical. Aggression can be further divided into either reactive or proactive aggression. Reactive aggression is responding to someone else’s behaviour—this is where children are provoked by others. Proactive aggression occurs for seemingly no reason—the child has not been provoked in any way (Dodge and Coie 1987 cited in Trawick Smith 2000). Any aggression in children’s services needs to be dealt with by caregivers. There needs to be clear, consistent rules for children so they understand what is acceptable and not acceptable with agreed consequences for behaviour. Caregivers need to praise and reinforce when children are displaying the appropriate behaviour. Understanding aggression is an important part of understanding how to foster social development and to know what normal levels of aggressive behaviour are for children at different stages bullying Bullying Bullying is a form of aggressive behaviour that begins to emerge in early childhood and unfortunately is common in middle childhood. Did you experience bullying as a child? For boys, bullying is more likely to be physical or name calling such as ‘four eyes’ for children with glasses, while for girls the comments are more likely to be passed in an undertone, and the behaviour to be more social exclusion than physical. For example, a group of girls is more likely to ‘gang up’ and exclude another girl because ‘she smells’ and use moving or turning away as a form of exclusion. This form of bullying is less obvious to carers, but is still bullying. Activity 6 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 13 Encourage children to express and manage feelings appropriately Activity 7 14 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 Support children’s various levels of interaction and participation with others during play Joining groups and initiating interactions with peers The ability to join groups of other children and the desire to do so begins at an early age and progresses through a developmental sequence. Mildred Parten an early theorist focused on the different types of social play. Parten observed children in the first half of the 20th century. In her research she discovered that children of different ages actually played together differently. They were capable of different levels or categories of social play. Her categories of social play are still a useful tool to help focus on how social play changes and develops at different stages of our lives. (Beck (1996)) Social play Ways children join in with other children So far we have looked at the theory behind why children play differently at different stages of their development. Have you also noticed though that some children are extremely skilled at entering play and organising games while other children can find it more difficult? There are a number of different ways children can join other children and access their play. These include: • • • • • standing nearby and watching, waiting for an invitation to join going up to the child or children and saying: 'Can I play?' sitting next to and engaging in a similar activity in the hope they are included asking other children to play with them telling carers they want to join in a game. Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010 15 All of these are appropriate ways of gaining access to a group. Sometimes, however, children will have learnt inappropriate ways of accessing groups such as joining the play uninvited and ‘taking over’ or destroying the construction or collaborative project the children have been working on. It takes much care as a childcare educator to deal with these situations. It is not enough to simply let the child know that the behaviour is inappropriate. We also need to give the child the skills to be able to join in play appropriately. We can do this by: • • • • modelling appropriate ways to join in play: 'Hi John and Simon, I see you are building an airport, Can I help?' giving the child the appropriate language to use supporting the child’s attempts at joining in play situations by being there to monitor the reactions of the other children fostering the child’s friendships with other children and groups of children. You will learn more about this in the next section. Consider this scenario. Hannah sets out a craft activity. There are differently-sized pieces of paper to work on and a central area to collect materials from. Hannah explains to the group that they can work on their own or with a friend to create what they like. While the children choose to either work together or with a friend, Shari sits on the floor at the edge of the group. Hannah takes her a cushion and says: ‘Do you want to watch for a while, Shari? Here you go, make yourself comfortable.’ Hannah has respected Shari’s right to watch, while catering for the social needs and abilities of the others and allowing them choices. There is naturally a balance between respecting a child’s right to watch and encouraging socially unconfident children to enter a group. You need to observe all the children in your care closely and watch for their cues that indicate they would like to participate but are not sure of their skills. Activity 8 Children with disabilities may need even more collaboration or direction from adults. This website gives a range of considerations and strategies: http://www.pediatricservices.com/parents/pc-28.htm Activity 9 Activity 10 16 Diploma of Children’s Services: CHCFC503A: Reader LO 9307 © NSW DET 2010