new cambodia report introduction

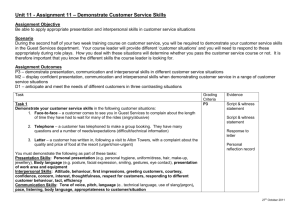

advertisement