quilomboreport-Abrams-Maranhao

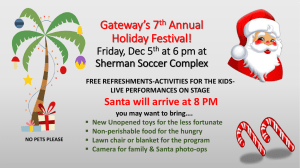

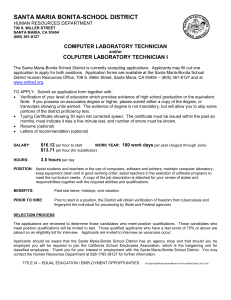

advertisement

A Report on Three Quilombos in Itapicuru-Mirim By Leonard Abrams HISTORY The word “quilombo,” which has its roots in several West African languages, including what is now Congo and Angola, translates roughly as “encampment.” During pre-slavery times, it denoted settlements of runaway slaves in Brazil. Another term for the same type of community is “mocambo.”2 The creation of such communities was not unique to Brazil, but rather they occurred virtually everyplace in the New World in which slaves were imported from Africa.3 The word is also used for settlements organized by inhabitants of abandoned plantations who maintain traditional lifestyles. Among the French, Dutch and British colonies the term “maroon” (“wild”) is used to refer to runaway slaves or descendent of theirs who maintain such an identity,4 while in Spanish-speaking areas the word “palenque”5 (“palisade”) refers to such settlements, as they were often fortified. Today, “quilombo” refers generally to rural communities of blacks whose way of life, due to geographic, racially based and/or socioeconomic isolation, is distinct from Brazil’s mass society and reflects the African antecedents of its inhabitants. Researchers have identified over 700 communities6 as quilombos since the installation of a democratic government there in 1988, though the true number may eventually run into the thousands. The majority of these actually began as plantations, as many plantation owners abandoned their land for economic reasons both before and after the abolishment of slavery in 1888,7 due to decreasing prices for their produce, frequent bouts of political instability,8 and the undercutting of the value of slave and later freedmen labor by European and Japanese immigrants. The designation of “quilombo” carries political freight in this moment in history, as there has been and continues to be conflict over the ownership of the land where many quilombolas live and farm today. According to the 1988 constitution, put in place with the return of democracy to Brazil, communities so designated may receive legal title to their lands.9 As Brazil’s transportation network improves, land formerly ignored by the outside world has increased in value, drawing the attention of the historically ubiquitous type of estate-holder in Brazil who uses theft as a means of acquisition.10 CURRENT CONDITIONS The communities covered in this study are the associations, or villages, of Morros, Santa Joana and Santa Maria dos Pretos (Santa Maria of the Blacks) of the municipality of Itapicuru-Mirim in the state of Maranhão in northeastern Brazil. The author spent three weeks in the communities, staying at the homes of Diomar Francisco da Conceição and João Batista Sousa Pereira, the presidents of Santa Maria and Santa Joana, respectively. These communities were part of a plantation of 9,000 hectares. The plantation, established over 300 years ago, was given, or abandoned, to its African-American inhabitants upon the abolishment of slavery in 1888. Since that time various incursions have been made by nearby white ranchers, resulting in the loss of 4,000 hectares. During the past several decades, such incursions have been contested and, with the use of public demonstrations and other forms of political pressure, repulsed without bloodshed. 2 The quilombolas’ cause has been taken up by a number of left-of-center political groups in various manifestations since the return of democracy, with varying degrees of support by their objects. The first project of the systematic mapping of quilombos was initiated in Maranhão in 1988 by the Negro Life Project (PVN), together with the Center for Negro Culture (CCN) and the Society for the Defense of Human Rights in Maranhão (SMDDH).11 These groups and others like them across Brazil continue to promote quilombolas’ rights, and also administer some health, education and development projects. As it happens, while the majority of voters in Santa Maria supported Inacio da Silva (“Lula”) of the Workers’ Party (PT) in the presidential elections of 1994 and 1998, the voters of Santa Joana largely supported Fernando Henrique Cardoso of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, the winner of both contests. It may not be coincidental that electric service stops just short of Santa Maria. Still, Diomar Francisco, president of Santa Maria, was able to persuade the municipality to send a bulldozer to help build a makeshift bridge across the iguapare (creek) named Ipiranga so that cars could drive to the village for its anniversary celebration. Morros, Santa Maria and Santa Joana, like the majority of quilombos at present, exist in a legal limbo as they await title to their lands. Aside from the sporadic attempts at depredation and occasional delivery of services of the kind mentioned, they are largely ignored by the outside world. The communities, which together contain roughly 1,000 persons, have no medical facilities, plumbing or schools, apart from the elementary-level schools run by the quilombolas themselves. All of the buildings are handmade from clay. 3 The three quilombos are governed each by a president who is elected by residents 16 years of age and older. The term is four years; it is an unpaid position. Morros is the first village one encounters on the single-track dirt road that serves as a main street, followed by Santa Joana, Santa Maria and other communities beyond. The road branches from a considerably wider unpaved highway that terminates in the town of Itapicuru-Mirim 19 km away. None of the residents owns a motor vehicle, though many make use of bicycles and burros, while a few keep horses. The quilombos studied here conduct for the most part a subsistence economy, in the sense that they produce largely for their own consumption and consume most of what they produce. Farming is the major occupation. The major draw upon leisure time is the planning and enactment of social events, which include religious ceremonies, commemorative events, dance parties and soccer matches. The word used for a social gathering, “brincadeira,” employed equally for prayer meetings and dance parties, is also commonly translated as “game” or “joke.” A trip into town can be had by truck every few days for one real. A bicycle ride into town during the dry season is a fair bit more strenuous than traversing the length of Manhattan; during the rainy season the roads are often impassable, increasing the isolation of the quilombolas. This is partially offset by the use of small canoes on the Ipiranga, which wends its way through numerous communities until it reaches the sizable Rio Itapicuru hard by the town. The Ipiranga is only navigable during the rainy season. Itapicuru-Mirim, a modest community of 5,000-7,000 in which bicycles far outnumber automobiles, is some 100 km from the state capital of Sao Luis, a seaport of 700,000. 4 A small community of blacks resides in Itapicuru-Mirim, most of whom have relatives in nearby quilombos. Diomar Francisco, president of Santa Maria, keeps a home in the town, one reason being that his children may attend the public school. A few other relatively prosperous quilombolas do the same, or else have their children stay with relatives in town so that they may be educated in modern fashion. While most young adults here are literate, many just a few years older are not. Reading material, apart from the Bible, is not a common sight. A half-dozen or fewer families have televisions, which receive a poor signal. Dance parties aided by small sound systems are thrown frequently. Forro and roots-reggae music are de rigeur for these. Apart from drums, there is little evidence of art or craft-making, aside from the most utilitarian, such as weaving of plant fibers and toolmaking. Cultural expression occurs mainly through festivals and ceremonies. In 1999, electrical power service was extended to Morros and Santa Joana but not Santa Maria, which is about the size of the first two together. Each dwelling along the main street of the first two villages is connected to the power grid and has a meter. Most of these are lighted by one or two naked bulbs. Some families own bottled gas-powered stoves; all own at least some manufactured cooking and dining utensils, and sleep in commercially made hammocks or beds. Kerosene lamps are used by those who lack electricity. Most people use manufactured toiletries; all wear store-bought clothing. Santa Joana has a water tower with multiple spigots, supplied by an electric pump, while Santa Maria has a similar water tower supplied by a diesel pump, both of which were erected during the past few years by the municipality. Most inhabitants, however, find it more convenient to draw their water from the Ipiranga, or from wells or springs 5 nearer their houses. The water-hauling is done by women, who balance plastic buckets or ceramic vases on their heads. Despite the lack of most modern devices, there is little sign of suffering or discord. Parents are rarely seen disciplining their children, who nonetheless do not appear disruptive. Food is not scarce and theft, with the possible exception of bicycles, is rare. Inebriation is not a rare occurrence, however, and at least two residents appeared to regularly treat the community with drunken harangues. Both of these men appeared to be marginal members of the community: one was considered mentally unbalanced, while the other was the itinerant carpenter. They were largely ignored when in this state. While the festivals observed appeared entirely peaceful, some residents talked about trouble erupting during public events in which alcohol was freely consumed, which is to say most of them. Municipal authorities may be called to help police such events.12 There does appear to be a slightly higher incidence of undersized individuals compared with typical communities in the Northern Hemisphere, which may have to do with the relatively small proportion of protein in the typical diet. Modern medical treatment, which is available only in the town, is augmented with herbs and animal parts and extracts, as well as healing via Macumba ceremonies. CURRENT PRACTICES Food Production Mandioca Mandioca (also known as manioc, cassava and yucca) is a staple food in this community, as it is in much of Brazil as well as in tropical lands all over the world. 6 Mandioca is native to South America, and the quilombolas’ method of cultivating and processing it is essentially the same as that of many Native American groups, with some improvements from the modern world. The cultivation of mandioca starts with the slash-and-burn method of field clearing typical in much of the tropical world. This community supports an individual who pays five reals for the right to harvest the charcoal in a typical field of one hectare or more. The charcoal is sold as a cooking fuel. Pieces of mandioca root are planted several feet apart; they grow to become individual plants, eventually producing mandioca tubers. The earth, which, as is most often the case in the tropics, is poor and contains little topsoil, readily supports the mandioca plant, which explains the prevalence of mandioca as a tropical staple. The tubers are abundant and easily pulled from the soil by hand. The mandioca tubers are then peeled, soaked in water to soften them, and shredded, the latter task done with the use of what appears to be the only machine used by these quilombolas in food preparation. This shredding device consists of a wooden hub fitted with steel teeth, which is spun by a rope belt connected to a wooden wheel several yards away. The wheel is cranked by hand. After the tubers are shredded, the mass is stuffed into a “tapiti,” a long, tube-shaped basket of woven plant fibers similar to the children’s toy that many in the Northern world know as “Chinese finger cuffs,” which narrow when pulled. This basket, woven into loops on either end, is set perpendicular on a rack and stretched with the weight of a person, then tied in its stretched-out position for perhaps an hour. The effect is that excess water is wrung out of the mass. 7 The mass is then expelled from the tube and crumbled through a coarse sieve, after which it is then raked with a hoe-shaped tool in a large iron pan of several feet across that makes up the roof of a clay oven. (Traditional Native Americans use a handmade ceramic pan.) Wood and plant fibers are burnt inside the oven. After about 3/4 of an hour of this toasting process, the resulting coarse “flour” (“farinha” in Portuguese) is laid out on a plastic sheet to cool. The final product is packed in large commercially purchased sacks. Farinha is primarily used by the quilombolas, as it is by a great many Brazilians, to thicken and add calories to most dishes, which usually consist of meat, poultry or fish in a sauce, served over rice. It is also used by the quilombolas to make a kind of cake, and can also be fermented into liquor, which is sold but not produced in this community. Equally importantly, farinha is the leading cash crop of the community. There are two or more farinha factories, known as “fornos” (ovens) in each village. The farinha is taken to market in the town of Itapicuru-Mirim several times per year in lots of two metric tons or more via a hired truck. Most of this work is performed during the dry season. The quilombolas receive the equivalent of six U.S. cents per pound, which even in this location is not very much money for the effort involved. Rice Perhaps the most important food crop in the community is rice: a typical dish here consists of what a Northerner would consider a very large pile of rice, topped by a modest amount of meat, poultry or fish in a sauce. Rice is well suited to this climate and terrain, as many fields here are flooded during the six-month rainy season and require no additional irrigation. Aside from the slash-and- 8 burn method, the rice fields are cleared with the help of commercial herbicides. Diomar Francisco’s field of approximately five hectares yielded 1,350 kilos of rice. The rice is dried in outdoor bins during the dry season and stored in its unthreshed state in indoor bins or in sacks. It is polished by pounding in mortars. This last process is possibly the most common and arduous task in food preparation, performed largely by women. The speed and productivity of the pounders of rice (as well as those of babassou nuts and of the breakers of babassou cocos) are points of pride and contention. Babassou In the babassou palm, with its fruit, the babassou nut cluster or “coco,” is one of the few commodities in which this community is rather uniquely wealthy. Thousands of the palms grow here, providing a bounty of nuts, palm fronds for roofs and weaving material, and the edible heart of the palm. The babassou nut, though fibrous throughout, yields a nutritious, high-quality oil, somewhat similar to but finer than that of the coconut, and the fibrous matter surrounding the nut sections can be processed into a cocoa-like powder. The nut can be eaten raw but is more easily consumed when first dry-roasted in a pan. The babassou is underexploited as a food and a cash product because of the nature of the coco. The coco, which resembles a large brown goose egg, is extraordinarily hard and tough. Extracting the nuts, which are shaped somewhat like a section of orange and of which there are typically three to six, entails striking the coco with a dense wooden stick or mallet against an upended axe head. The work is arduous; a day’s work of cocobreaking yields approximately eight kilos of nuts, which can be sold for 30 centavos per kilo, or US$1.00 for the day, to a local purchaser. The fact that a fair number of 9 quilombolas resort to this work is indicative of the scant opportunities for their participation in the mainstream economy. With that, certain individuals noted with some pride that coco-breaking afforded them the wherewithal to purchase needed commodities. Machines exist that have been adapted to aid in the extraction and processing of babassou nuts; these devices are in use in some Native American communities, extractive reserves and on certain other quilombos. But this community, far removed not physically but socioeconomically from the mainstream society, has not been able to acquire such basic technology. Villagers complained that the price of babassou nuts had fallen over the years such that they could no longer buy needed goods such as clothes with the money earned from extracting them. This may reflect the use of extracting machinery in other communities, as well as the availability of cheaper commercially processed vegetable oils. Babassou oil is prized for the flavor it adds to foods, and so there is a market for it in the community and in neighboring villages. Women produce the oil by roasting the nuts, crushing them in a mortar, squeezing the mass in water to extract a milk, boiling the milky mixture and skimming the oil from the top. The residue is eaten as well, either over farinha or by itself, sweetened with cane sugar. Homemade babassou oil can be sold for 3 reals (US$1.20) per liter in the villages. A family business in the town, which purchases the nuts from gatherers and produces babassou oil with the aid of an electrically powered nut grinder, sells the oil for 2 reals per liter. This is roughly equivalent, considering the premium paid for distributing products to outlying districts. The residue from the commercial operation is sold as animal feed. 10 Most quilombolas here more often buy commercially produced soybean oil at one of the two general stores in Santa Maria for 2 reals per liter, though babassou oil is universally acknowledged to be superior. Two other products result from the process. Babassou-husk charcoal is a preferred cooking fuel, and plump white grubs are found in some cocos. Known as “gongo” (an African-derived word), they are used as fishing bait and also fried in their own fat, which is used as a skin balm. Fried gongo are also eaten. They are delicious. Husbandry The quilombolas raise chickens, pigs and cattle, most commonly the first and rather little of the last. Due to a lack of refrigeration, cattle are typically sold wholesale in the town, and when a pig is slaughtered most its components are immediately sold off. During the author’s stay, an entire cow was purchased for the use in large part for the anniversary celebration of Santa Maria, though private individuals had spoken for much of the animal before it was slaughtered. One woman in Santa Maria, a recipient of a “micro-loan” from a regional bank, owns a small chicken farm. The operation, which consists of buying chicks and corn and selling pullets, appeared successful in spite of her lack of literacy. The typically small pig farms similarly consist of the raising of juvenile pigs into young adults with the use of commercial feed, augmented by farinha, the residue of the babassou oilmaking process and household scraps. The relatively few number of quilombolas who raise cattle keep small herds of a dozen or fewer head. More status accrued to these farmers than those who raised lesser animals. Milk, at least during the dry season, was not in any great supply from these 11 cattle and only satisfied the needs of those households. Quilombolas more commonly bought commercially processed powdered milk to add to their coffee. Hunting The quilombolas also made use of game, which includes deer, wild pig, a variety of birds, armadillos and other rodents, as well as snakes and turtles. Hunting is a favored pastime, though many hunters came up emptyhanded for their efforts and the woods seemed strangely devoid of the noise of birds and the rustle of even the smallest animals, such as one takes for granted in the temperate North. Much of this could be explained by the fact that small animals in the temperate North are unused to being hunted, though it may also indicate the relative lack of wildlife in many tropical forests in the dry season. Animals appear to be treated rather casually in these communities; pets such as are kept are generally not fawned over but largely serve a purpose, either as watchdogs or, in the case of birds, as sources of amusement for the owners. An armadillo purchased by the author was casually executed with hammer-blows to the head, while in another case a child, petting a quail about to be prepared for dinner, just as casually wrung its neck a moment later. These acts were done with neither cruelty nor ceremony, though it is not uncommon for a child to amuse herself with a terrified captive wild bird. Housing All types of shelter in the quilombos are built in essentially the same manner: A rectangular frame of wooden poles is lashed together and the spines of palm fronds are then lashed, inside and out, to the frames in intervals of approximately a hand span. Clods of earth are piled into the space thus made, and the space between them is filled in and 12 smoothed over with mud. This work is done by hand, though the walls of some houses are smoothed over with a straight-edged piece of wood or other material and thus made to resemble a plaster wall. A few of these finished walls are painted. Some less ambitious structures have walls of palm fronds. A typical house is roughly 15 feet wide and perhaps 50 feet long and contain several interior walls to create a living room, one or more bedrooms and a kitchen. Doors and window frames are usually made of sawn wood bought in town, though many houses had doors of woven palm fronds and windows with bars made of palm frond spines. Glass windows are rare. The roof is made by lashing overlapping fronds of the babassou palm. Sometimes synthetic, industrially made cord is used for lashing, though bark strips are more common. Floors are made of packed earth. A roof can last up to ten years, a house up to 20. This type of wattle-and-daub building technique, with palm-spine ribs delineating mud walls, can be seen in many regions of West Africa today, though conical houses are more typical there.13 Some quilombolas’ kitchens contain clay stoves powered by charcoal, while many people do all their cooking in a pot over three stones. A few households own modern stoves powered by bottled gas. Cooking and eating utensils are of the kind typically seen in discount houseware stores all over the world: aluminum, stainless steel and plastic, mostly imports from Asia. While a number of houses contain one or more typical beds, most quilombolas sleep in store-bought cotton hammocks. 13 Craft Carpentry The central houshold implement is the mortar and pestle. It is used daily to polish rice. Rice grains, on or off the stalk, are placed in the mortar and pounded with a heavy wooden pestle several feet in length for ten to fifteen minutes until the husk and most of the outer grain is removed, resulting in a blonde, nearly white grain. The chaff is shaken out in a shallow basket. The mortar and pestle are also used to mill corn and wheat, to mash babassou nuts and to crush coffee beans and salt. After hewing the rough shape of the mortar with an axe, the carpenter places hot coals and coco husks to burn the area where the bowl is to be made, then removes the burnt portion with a chisel, as in the process of making a dugout canoe. Softer woods, worked more quickly, are made into mortars more cheaply than the harder woods, the hardest of which can last a lifetime as opposed to a few years. The itinerant carpenter in residence, of Portuguese extraction, charged from ten to 20 reals for a mortar and $R2.50 for a pestle. A mortar can take one or two days to make, a pestle about an hour. The carpenter and his wife had taken up residence in an unused house at the beginning of the dry season and expected to stay as long as his products were in demand. He said he also made canoes, stools, tables and cupboards, but there was little call for them here. Plastic chairs are more common than wooden ones, presumably due to the cost of the latter. 14 Drum-making One of the two kinds of drums seen in the community, which are used ceremonially, are made locally by a quilombola who also farms. A portion of hollow tree trunk several feet long is sawn from a fallen tree and finished inside and out with a steel chisel. A raw, dried animal skin, typically of deer or wild pig, is stretched over one end of the drum and held in place by wooden pegs placed into holes around the drum’s rim. The skin is later tightened by holding the drum close to a fire. Several of these conga-type drums are used together in Macumba ceremonies in relatively complex multirhythmic arrangements, as opposed to the lighter drums with steel bodies that are used in processions and not made in the villages. Ceremonies, Festivals and Religious Practice Macumba The great majority of quilombolas consider themselves Catholics of some devotion; however, that does not impede their practicing the brand of West Africa-derived worship they refer to as Macumba, which contains elements from from the Yoruba and Kongo cultures and is popular among many blacks as well as other racially defined residents of the municipality of Itapicuru-Mirim. Forms of worship that syncretize Catholic, West African and Native American practices, including Umbanda and Candomble, are common across Brazil. It should be noted that while some Brazilians find the word Macumba offensive, it is the chosen appellation of the inhabitants of this area. Protestant ministers also preach itinerantly in the quilombos, though their progress is often hindered by their hostility to many aspects of Macumba, the polytheistic and 15 propitiatory among them. The Protestants’ preoccupation with the figure of Satan finds an outlet in the figure of Exu (Eshu)-Alegba, the Yoruban deity that embodies human potentiality and mischief, among other things. João-Batista, who aside from being president of Santa Joana is also the leading Macumba practicioner and referred to as the “pãe de santo” (father of the saint) of the community,14 told of a North American minister who visited to preach “that Exu was the owner of the dark side of Umbanda. But we thought otherwise.” The Catholic church, with its similarities in practices, such as votive offerings, the tripartite deity and the numerous lesser figures of saints, angels and human intermediaries, has often proved more sympathetic to these African-derived practices.15 Still, before emancipation – and even after16 – Macumba ceremonies were often outlawed.17 The Macumba of the quilombos is part of a broad-based practice that is found in much of the Northeast of Brazil. In the town of Itapicuru-Mirim are several Macumba temples, one of which dwarfs any structure in the quilombos. João Batista and his brother Martin Pereira de Sousa, who lives in town, maintain a small temple in the back of the brother’s residence. The Macumba as practiced here involves ritual drumming, singing and dancing in specially made garments, and specific rituals. Catholic icons and pictures of saints are always present; specifically African and/or Negroid imagery and icons are not. However, the central aspect of the ceremony, the calling down of spirits into the individual, are clearly Africa-derived. When the spirits are drawn to inhabit the body of the worshipper, they can be entreated to help in various ways.18 16 The Feast of Santa Filomena One major festival the writer was able to observe was the Feast (Festa) of Santa Filomena. In this all-day-and-night affair, a very long tree trunk, trimmed and scraped to resemble a ship’s mast, was taken from the forest and carried by the men through the village of Santa Maria to the accompaniment of drums and singing and much of the population. The procession stopped at each house and entered with the base of the mast to exchange blessings for food and drink, after which the mast, topped by a white flag, upon which was drawn a blue dove, was planted in the village square to much prayer, song and drink. The prayers and celebrations continued until dawn. The festival was attributed to Africa by the participants.19 A similar festival can be found in Cape Verde, a formerly Portuguese-held island off West Africa that was used as a slaving station as well as for plantations.20 A significant part of the festival concerns praising the forest, which has a basis in indigenous as well as African ceremonies. In a society so dependent on the forest for its sustenance, these elements are likely reinforced as well as augmented by contemporary experience. Occurring during the dry season, a time when the year’s harvest has largely been completed, the festival is also an offering of thanks, propitiation and fertility. This last is demonstrated by the entrance of the mast through the doorway of most dwellings along the route, at which time the base of the mast was doused with cachaça. The celebration includes a sort of competition of poetry, as the men gather around the erected mast and take turns singing lyrics both old and new that pertain to their lives in a witty manner. Each time a participant finishes his verse, he takes a drink of cachaça from a basin that has been filled for the purpose. 17 While this is happening, the women, and a few men as well, gather in the church, which shares the village center with the school, to drum and sing prayers and acclamations in front of a candle-lit altar containing images and icons of Catholic saints. The Anniversary of Santa Maria dos Pretos The 300th anniversary celebration of Santa Maria dos Pretos took place on August 9th of 2001, though it is unclear whether the plantation was in fact exactly 300 years old or whether the age given was approximate. The focus of the celebration was a dance party, aided by a large, generator-powered sound system, professional DJ/master of ceremonies and a cash bar proffering iced-down beer and soft drinks. A stockade of large palm-frond spines was erected around the village square, a packed-earth clearing containing a school and a church, and an admission of 2 reals was charged. Preceding the dance party was a "futebol" (soccer) game pitting a neighboring quilombo against a nearby caboclo (rural Portuguese/ indigenous-derived) village. Perhaps 300 persons attended the event, which drew from the town as well as nearby villages. Despite the secularity of the event, the church was as busy as the schoolhouse, which served as a discotheque. Inside, parishioners sang and chanted prayers in front of a candle-lit altar. In the square, children examined the wares of a half-dozen portable stands selling candy and cigarettes. Plates of food were also sold, though a team of women had been employed all day in cooking a free dinner for the entire resident community, which was served in shifts early in the evening from the schoolhouse. It is noteworthy that public gatherings of any size include a meal freely given to all in attendance. 18 Also noteworthy is the fact that, while the village had raised 1,500 reals for the event, it appeared to be common wisdom in the quilombos that the purchase of farming or processing machinery, such as an 800-real babassou nut-crushing machine, was beyond the community’s means. OBSERVATIONS The absence of financial means and human misery are firmly paired in the First World mind, to such an extent that even among those most open to other social systems, to suggest otherwise can constitute a taboo. The people discussed in this study are, in terms of monetary income, remarkably poor. Yet this society of quilombos appears to be quite functional, in some ways more so than certain subsets of people in the First World who are materially far richer. Once again, some in the First World willing to embrace this thesis would attribute it to the absence of the ills of modern-day life, which implies that what is needed is simply to subtract an existing element that one has chosen to keep. This may be due to the condition that it is more palatable than to admit that another society may possess something lacking in one’s own, for then one must admit that all is not within one’s own power. The simple fact of living in a remote rural setting without financial means does not constitute a recipe for a good life: a workable system must be employed. The quilombolas, rather than identify themselves as part of a lower tier of a larger society, have drawn upon their African heritage, with the admixture of Western and indigenous 19 elements and have succeeded, with little more than what the local environment provides, in providing for their psychic and material needs. It appears that, specifically, it is the organization and enactment of African-based ceremonies and festivals, which involve substantially the entire society, that binds the community into a cohesive whole, and fosters the commonality that gives it its purpose. Additionally, elements that focus on a more contemporary sense of black pride, based as it were on the North American model, contribute in a smaller way to such a sense of unity. 20 BIBLIOGRAPHY Books Africa and Africans Paul Bohannan, Philip Curtin. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1988. Anthropological Filmmaking Ed. Jack Rollwagen. Reading, PA: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1988 Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy Robert Farris Thompson. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1983 Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality In The African Diaspora Sally Price and Richard Price.--Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1999 Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas Ed. Richard Price. 1st ed. Garden City, NY: Anchor-Doubleday, 1973. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1979. “Maroons In The Province Of Maranhão, Brazil” Matthias Röhrig Assunção. Essex, England: University Of Essex, 1999 in João José Reis and Flávio Gomes (ed.), Liberdade por um fio. História dos quilombos no Brasil (São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1996), pp. 433-466 Articles [Note: Internet links have been included where possible as a convenience to the reader, though not all online articles are complete and some are not available in English.] “Afro-Latin America” Elsa Chanduvi and others. SIRS Researcher, Winter 1997 pp.1-10 from Latinamerica Press, 1997, Lima, Peru 21 http://faculty.ed.umuc.edu/~jmatthew/articles/afrolatin.html “Creativity and Resistance: Maroon Cultures in the Americas” Kenneth Bilby and Diana Baird N'Diaye Originally published in the 1992 Festival of American Folklife catalogue; reprinted from the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage of the Smithsonian Institution. http://www.si.edu/maroon/educational_guide/10.htm “Former Slave Havens in Brazil Gaining Rights” Larry Rohter. The New York Times, January 23, 2001 http://www.mre.gov.br/acs/interclip/jornais/janeiro01/nytimes23a.html “For Some Brazilian Slave Descendants, Home at Last” Stephen Buckley. The Washington Post, January 28, 2001 http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wpdyn?pagename=article&node=&contentId=A54182-2001Jan27 “The Negro Life Project” Koinona Ecumenical and Service Society Web site, October 2001 http://www.koinonia.org.br/projetos/tn/4/historia.htm “Origin and Description of the Quilombo in Africa” Kabengele Munanga. RevistaUSP, University of Sao Paulo, Number 28 http://www.usp.br/revistausp/n28/kabengele.html “The Quilombos” Ministry of External Relations, Brazil, 1995 http://www.mre.gov.br/ndsg/textos/quilom-i.htm “The Slave King” Robert Nelson Anderson III. Brazzil magazine, October 1995 http://www.iei.net/~pwagner/gooddeeds/zumbi.htm 22 5 “O Afro-latim a América” Elsa Chanduvi e outros. Investigador de SENHORES, Inverno 1997 pp.1-10 de Latinamerica Press, 1997, Lima, Peru, http://faculty.ed.umuc.edu/~jmatthew/articles/afrolatin.html 6 “Para Alguns Descendentes de Escravo brasileiros, Casa afinal” Stephen Buckley. O Poste de Washington, 28 de janeiro de 2001, http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&node=&contentId=A54182-2001Jan27 7 Ibid. 8 “Cor castanha Em A Província De Maranhão, Brasil” Matthias Röhrig Assunção. Essex, Inglaterra: Universidade De Essex, 1999, no João José Reis e Flávio Gomes (ed.), Liberdade por um fio. História dos quilombos nenhum Brasil (o São Paulo, das de Companhia Letras, 1996), pp. 433-466 9 “Os Quilombos” Ministério de Relações Externas, Brasil, 1995, http://www.mre.gov.br/ndsg/textos/quilom-i.htm 10 Ibid. 11 “O Negro Vida Projeto” Koinona Ecumenical e Sociedade de Serviço diário Web-baseado, 2001 de outubro, http://www.koinonia.org.br/projetos/tn/4/historia.htm 12 “Só é ruim se houver pessoas lutando. Antes de as brigas estavam com punhos, e agora as pessoas atiram e apunhalam um ao outro, e isso é pior. Quando a briga começa que eu saio do lugar. Todo o mundo corre fora.” —O informante não identificado 23 “Se alguém vem e quebra que coisas iam ter que pagar que e eu terei que quebrar a perna dele. Não, eu sou sério. Se é Tiago que eu terei que quebrar a perna de Tiago e o enviar à polícia pela manhã, porque eu não vou levar a perda. Mas eu falei com o prefeito e talvez dois policial virão. Se eles vêm que nós não temos que preocupar sobre os encrenqueiros, a polícia pode levar ao cuidado deles.” —O Diomar Francisco 13 Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy Robert Farris Thompson. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1983, pp.198-206 14 Ibid., pp. 107-108 15 “Eu sou um católico de meu próprio modo porque eu rezo e eu chamo em Deus. Nós não somos os protestantes porque os protestantes não gostam de Macumba e eles não gostam da igreja católica, e o macumberos como a igreja católica porque o padre celebra a massa no quarto de Macumba.” —A Patricia de Sousa 16 “No passado era mesmo, muito difícil. Até mesmo a polícia foi chamada. Nós iríamos para prisão. Eles chamaram isto a coisa de um Diabo.” —A Patricia de Sousa 17 “Quando o quilombolas ainda estavam trabalhando como slaves…it foi proibido para dançar para tocar os tambores. Os donos da plantação não os deixariam jogarem. Mas eles iriam para os bosques e fariam uma fogueira e todos o quilombolas viriam adquirir a liberdade deles/delas ao redor.” —O João Batista 18 “Nós vestimos com estas roupas longas assim trabalhará o modo que estava trabalhando em cima de lá, e nós dançamos assim eles virão, e nós entramos em um transe e quem falará é o que veio, assim ele fala tudo que que ele quer e nós não estamos atentos. E quando entra longe de na pessoa que ele não sabe o que ele disse. Isso é a origem de Macumba… .We se vestem a rigor, nós vestimos algumas decorações, um pano no cabelo, nós vestimos um rosário [colar] e então nós dançamos, e eles chegam e nós desmaiamos e só voltamos depois…. “Há muitas coisas o doutor pode solucionar mas há outras coisas que só a Macumba pode solucionar… .We chamam nos santos, os deuses, o orishas, e assim a pessoa sentirá bem…. “As pessoas vêm aqui para solucionar problemas com uma pedra no rim, pessoas que são batidas na cabeça com uma garrafa, nós os abençoamos, nós os ajudamos… .We pôs a mão na cabeça tirar aquela coisa ruim deles.” — Patricia de Sousa 19 “A procissão vai de casa para morar. Se você não tiver dinheiro, traga cachaça…. Nós vertemos isto no mastro… .All as pessoas que levam isto estão bebendo… .We não partem até que eles nos dão algo que beber… .We adornam isto com laranjas, bananas, abacaxis, folhagens de palma e uma garrafa de cachaça… .We erguem para cima o mastro com cordas… .And nós estamos cantando e estamos cantando, elogiando a floresta: ‘A árvore de banana, a banana que eu levo de lá, A banana que eu comi era a banana eu levei de lá… '” — Sebastian Batista 24 20 “Isto também ereção de includes…the de um mastro, uma réplica do mastro de um navio que é vestido com filiais da oliveira selvagem ou a palma de coco… mastro de .The é colocado perto da entrada de uma igreja, para os ritmos de tambores, cantos, e batendo palmas. Navios de modelo levaram à mão ou usado como um symbolically de viagem de fantasia pelas ruas, parando para exigir presentes. … .The transportam, como o mastro de presente-porte, é um símbolo complexo….. Navios são festooned com brightly coloriu bandeiras… o molestamento de navio de .The de espectadores para presentes representa a agressão nas Ilhas através de navios de pirata…” —“Festividades tradicionais em Cabo Verde” por Gabriel Moacyr Rodrigues, Capa Verdean World Wide Web Site, um projeto colaborador da Capa mundial comunidade de Verdean, na Universidade de Massachusetts, Dartmouth, http://www.umassd.edu/specialprograms/caboverde/cvfestas.html “Former Slave Havens in Brazil Gaining Rights” Larry Rohter. The New York Times, January 23, 2001 http://www.mre.gov.br/acs/interclip/jornais/janeiro01/nytimes23a.html “Origin and Description of the Quilombo in Africa” Kabengele Munanga. RevistaUSP, University of Sao Paulo, Number 28 http://www.usp.br/revistausp/n28/kabengele.html “The Slave King” Robert Nelson Anderson III. Brazzil magazine, October 1995 http://www.iei.net/~pwagner/gooddeeds/zumbi.htm 2 “Creativity and Resistance: Maroon Cultures in the Americas” By Kenneth Bilby and Diana Baird N'Diaye http://www.si.edu/maroon/educational_guide/10.htm 3 4 Ibid “Afro-Latin America” Elsa Chanduvi and others. SIRS Researcher, Winter 1997 pp.1-10 from Latinamerica Press, 1997, Lima, Peru http://faculty.ed.umuc.edu/~jmatthew/articles/afrolatin.html 5 “For Some Brazilian Slave Descendants, Home at Last” Stephen Buckley. The Washington Post, January 28, 2001 http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&node=&contentId=A54182-2001Jan27 6 7 Ibid “Maroons In The Province Of Maranhão, Brazil” Matthias Röhrig Assunção. Essex, England: University Of Essex, 1999 in João José Reis and Flávio Gomes (ed.), Liberdade por um fio. História dos quilombos no Brasil (São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1996), pp. 433-466 8 “The Quilombos” Ministry of External Relations, Brazil, 1995 http://www.mre.gov.br/ndsg/textos/quilom-i.htm 9 25 10 Ibid “The Negro Life Project” Koinona Ecumenical and Service Society Web-based journal, October 2001 http://www.koinonia.org.br/projetos/tn/4/historia.htm 11 20 Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosopy Robert Farris Thompson. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1983, pp.198-206 “I’m a Catholic in my own way because I pray and I call on God. We’re not Protestants because Protestants don’t like Macumba and they don’t like the Catholic church, and the macumberos like the Catholic church because the priest celebrates the mass in the Macumba room.” — Patricia de Sousa 20 “In the past it was very, very difficult. Even the police were called. We would go to prison. They called it a Devil’s thing.” — Patricia de Sousa 20 “When the quilombolas were still working as slaves…it was forbidden to dance to play the drums. The owners of the plantation wouldn’t let them play. But they would go to the woods and make a bonfire and all the quilombolas around would come to get their freedom.” — Jean-Batista 20 “We dress with these long clothes so it will work the way it was working over there, and we dance so they will come, and we go into a trance and whoever will speak is the one who came, so he speaks whatever he wants and we're not aware. And when it goes away from inside the person he doesn’t know what he said. That’s the origin of Macumba….We dress up, we put on some decorations, a cloth in the hair, we put on a rosary [necklace] and then we dance, and they arrive and we black out and only come back afterwards.” — Patricia de Sousa 20 “The procession goes from house to house. If you don’t have any money, bring cachaça…. We pour it on the mast….All the people carrying it are drinking….We don’t leave until they give us something to drink….We adorn it with oranges, bananas, pineapples, palm fronds and a bottle of cachaça….We lift up the mast with ropes….And we’re chanting and singing, praising the forest: 20 ‘The banana tree, the banana I take from there The banana I ate was the banana I took from there…’ ” — Sebastian Batista “It also includes…the erection of a mastro, a replica of a ship's mast that is dressed with branches of the wild olive tree or the coconut palm….The mastro is placed close by the entrance of a church, to the rhythms of drums, chants, and clapping. Model ships carried by hand or worn as a costume voyage symbolically through the streets, stopping to demand gifts. ….The ship, like the gift-bearing mast, is a complex symbol….. Ships are festooned with brightly colored banners….The ship's harassment of bystanders for gifts represents the assault on the Islands by pirate ships…” — “Traditional Festivities in Cape Verde” by Gabriel Moacyr Rodrigues, Cape Verdean World Wide Web Site, a collaborative project of the worldwide Cape Verdean community, hosted at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth http://www.umassd.edu/specialprograms/caboverde/cvfestas.html 20 26 27