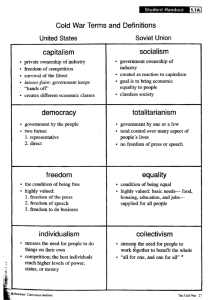

Types of economic Systems

advertisement

Twentieth-Century Economic Systems Through most of the twentieth century, the nations of the world have been divided, and some of their conflict was over their different economic systems. Since the fall of the Soviet-type, or "Communist," governments in eastern Europe, this division may seem to be a thing of the past. It might be hasty to draw that conclusion, though. In the 1930's, it seemed to many observers that capitalism had failed, and that the future belonged to one or another of the noncapitalist systems. A little more time proved that that impression was wrong -- capitalism came back to a dominant position, but it was a somewhat different form of capitalism. In early 1997, it seemed as if the non-capitalist systems have failed, and the future belonged to capitalism. But just as the perception of things in the 1930's was wrong, the perception of things in the 1990's may also be wrong. Indeed, by late 1998, problems for capitalist countries had mounted to the point that a major American newsmagazine could run as a headline the question "Who Lost Capitalism?" Certainly, there is something to be learned from the collapse of the Soviet-type systems, but what? Is the debate over economic systems over, or has it entered a new phase? Only time will tell. What we can do in this chapter is look back over the debates in the 20th century, and review a bit of what economists have learned from them and taught about them. The point of view will be that of neoclassical economics. (The Marxist view of capitalism is discussed in another appendix). Discussions of economic systems have usually focused on the ideal conceptions of the different systems and on the extent to which the ideal might be realized in the actual systems of the different countries. One fallacy we want to avoid is that of comparing the ideal in one case with the actual performance of another. That's not fair and can only lead to confusion. But ideals can be deceptive -- it is quite possible that one system might be preferable to another, as an ideal, but so difficult to realize in practice that in actual examples, it is worse. We shall have to look both at the ideal, and at the obstacles to realizing that ideal in practice. It is here that we may learn something from the failure of the Soviet-type systems in the 1990's (and perhaps also about the failure of the capitalist systems in the 1930's). The ideal economic systems have played a part in different ideologies and social movements, but the ideal systems are not the same thing as the ideologies and social movements. As economists have conceived them, the ideal systems of the twentieth century have been market capitalism, government-managed capitalism, central planning, market socialism, and labormanagement. The last three of these have played some part in socialist thinking, in different times and places, while central planning has also played some part in fascism and, in some countries, capitalism. This chapter will focus mainly on the ideal systems and the problems and difficulties of putting them into practice. Accordingly, we will first quickly summarize market capitalism as an economic system, largely drawing on ideas in other chapters of this text. We will say a little about different kinds of capitalism, including government-managed capitalism, and about the difficulties of putting market capitalism into actual practice, and about the social movements that challenged capitalism. We will then talk about ideal central planning, the difficulties of putting it into practice, and about two other non-capitalist ideal systems, market socialism and labor-management, and the difficulties they, too, face in practice. Finally we will try to draw some lessons from the collapse of the Eastern European Communist countries. Ideal Market Capitalism In a market capitalist system, capital and land are private property. Enterprises may be formed by individuals who can get access to land and equipment, either because they own it or can rent or borrow to get it, and who can hire labor or employ themselves. Enterprises organize and direct production, and they are operated for the private benefit of the person who organizes the enterprise. Private benefit is interpreted as profit, so we say that the enterprises maximize profits. In a capitalist economy or in any economy, production is limited by existing resources and technology. We can express this limit with a concept from neoclassical economics: The production possibility frontier. Once again, we will use the simplified production possibility frontier for Economia, which produces only machinery and food. Here it is, to help jog your memory. The idea is that economia can produce any combination of food and machinery on or below the curve. Figure 1 The economy can produce only combinations on or below the curve. But what combination of goods will be produced? Of course, that will be determined by and equilibrium of supply and demand, but we can skip over a many of the details from chapters 3-14 above. In an ideal market, production at market equilibrium will give the highest possible market value. Figure 2 The result is shown in Figure 2. In the Figure, the line indicated by Y1 shows all combinations of food and machinery that add up to the same market value a value of Y1. Similarly, line Y2 shows all combinations that add up to a market value of Y2, and line Y3 shows all combinations that add up to a market value of Y3. The slope of all three lines is the same, and it is the relative price of food and machinery -- the amount of machinery we have to give up in the marketplace to get one more unit of food. We see that Y2 is the highest market value that can be produced, and it can be produced only if the combination of food and machinery is on the production possibility frontier at point *. And it makes sense that an economic system based on profit would produce that amount. If it did not, some enterprise would be able to increase its profits by shifting its production toward a higher market value. But combination * is not just the greatest market value. In the ideal market capitalist system, the prices reflect consumers' "marginal benefits," and that means that the combination of outputs at * is efficient. Of course, there may be other things about capitalism that are more important than this. Some economists would argue that it is the creative act of forming enterprises and discovering new technologies that is most important, especially in the long run, and that even a capitalism that departs quite far from this ideal could still have great advantages. But this discussion summarizes the argument for market economies in neoclassical economics, and thus it summarizes the neoclassical ideal conception of capitalism. Kinds of Capitalism Enterprises in capitalism as Adam Smith and Karl Marx knew it were typically individual proprietorships. There were few corporations, and probably none in the modern sense, in Smith's time. Smith regarded corporations as hangovers from feudal times, and saw no future for them. This early form of capitalism was proprietary capitalism. One problem for proprietary capitalism is that these individual enterprises seldom got very large, by modern standards. This meant that many projects that could have been useful and profitable could not be undertaken by capitalist firms, because the projects were too large -- there were no enterprises large enough to afford them. Modern corporations came into existence to finance and administer these huge projects -- canals, railways, telegraph and telephone systems, gas and electric power distribution. (Nevertheless, government carried out the large-scale projects in many capitalist countries). The corporations became more predominant, transforming proprietary capitalism into corporate capitalism. The collapse of world markets in the period 1930-1940 threatened to destroy capitalism entirely. After some delay (and in the context of world war) governments stepped in to support capitalism by various means of regulation, controlling money supplies, and government expenditure. Thus, market capitalism was transformed into government-managed capitalism. Sometimes called a "mixed economy," because it relies largely on markets but partly also on government to direct the economy, this system has been predominant during the second half of the twentieth century. Conservatives deplore this, and there have been conservative governments pledged to return to pure market capitalism, from time to time, in most major capitalist countries. But they have been unable or, perhaps, finally unwilling to do it. No matter how ideologically committed, governments have not yet been willing to let markets find the way, fail if they would, and let capitalism be destroyed by the failure. But more than that -- in the conditions of the 1990's, it is hard to see how a pure market capitalism could exist at all. To move toward a more pure market capitalism, it has been necessary to privatize, reform regulations, and manipulate interest rates -- some of the largest government initiatives in the history of capitalism. But perhaps the future will be different. Problems of Capitalism In ideal market capitalism, the equilibrium outputs are efficient. Efficiency is important, but there are some criticisms even of ideal capitalism. Most fundamentally, the prices in the marketplace reflect consumer preferences. Thus, in ideal market capitalism, production is directed by consumer preferences. It is not clear that production should be directed by consumer preference, though. To say that production ought to be directed by consumer preferences (called "consumer sovereignty") is a value judgement, not a law of nature, and some people may disagree with it. Consumer preferences may be determined by addiction and persuasive advertising. Some may feel that esthetic and cultural values, or national traditions, should have a bigger role than the market gives them. These ideas are not by any means limited to those on the left. Traditionalist conservatives might want to stress traditional values rather than the tawdry vanities of the marketplace. Middle-ofthe-roaders might want to put more weight on things that consumers evidently don't prefer, objective benefits such as reducing fat and calories and heart attacks, and increasing vaccinations to reduce infection. Even in ideal capitalism, the distribution of property and income could be very unequal. Ultimately, the benefits and costs reflect the subjective preferences of consumers who have money to spend. One might want to put more weight on the preferences of people who cannot spend, that is, on the welfare of the poor. So even an ideal capitalism might have some shortcomings, depending on one's value judgements. But any real capitalism will fall short of the ideal, and real capitalisms have fallen short in several predictable ways: Monopoly and restricted competition may cause prices and output to deviate from the efficient ones, and they are likely also to increase inequality, especially if competition for labor is limited. Markets may not respond efficiently to cases where costs and benefits are "external," and public goods may not be produced in efficient quantities. Real-world markets may not move toward an equilibrium of supply and demand. Perhaps for some of the reasons discussed by Keynesian economics, or for other reasons, markets may settle into stable conditions quite unlike the equilibrium of supply and demand, and quite inefficient and non-optimal. One response to these criticisms is that government can step in and correct the failure of the market to provide the desired and (in some cases) efficient outcome. Governments can subsidize the poor and can subsidize or provide the goods and services that ought to be, but are not demanded by consumers, and the government can finance this out of taxes, including taxes on those goods that consumers demand although they ought not. Monopoly can be regulated and to some extent prevented through antitrust legislation. Regulation, taxes, and subsidies can be used to promote efficient outcomes in cases of public goods and external costs and benefits. Deliberate government spending, tax reductions, and interest rate manipulation may move the market system toward market equilibrium if it falls short for the reasons Keynesian economics envisions. But this is rather a long list of jobs for government, and if government does any large fraction of them, we no longer have market capitalism but government-managed capitalism. Freemarket conservatives will point this out, and will point out that, however imperfect markets may be, government too is imperfect. Just as markets will sometimes fail to deliver the outcomes we want, government too often fails to do the jobs we set for it. What it means in this context is that some of these failings of real-world capitalism cannot be remedied without risking a greater evil in government failure, and some cannot be remedied at all. Real systems are not ideal but imperfect systems, and real capitalist systems will fall short of our hopes on at least several scores. And that has been no secret for two hundred years. Challenges to Capitalism Ideal market capitalism says nothing about social classes. In principle, it might be a classless society -- that is, a society with only one class, without class divisions . The one class might be a class of yeoman market farmers. But, in practice, market capitalist societies have been divided between two classes with quite different conditions: employers and employees. The tension between the employer class and the class of employees led to socialism, an idea that arose in the first half of the 1800's. Socialists knew that the old aristocracies, from feudal times, had ceased to exist as a class. The revolutions and gradual changes of the two centuries before 1800 had eliminated the special role of the old aristocracy and transformed them (at best) into capitalist land-renters. The socialists looked forward to a future in which the class of capitalist employers would also be eliminated as a class, with the former employer class or their descendants having to work for a living as the vast majority already do. This would be a society with only one class, the working class; a society without class distinctions and thus a classless society. In the words of W. Arthur Lewis, a spokesman for the Fabian Socialist Society in the 1940's (and later a Nobel Memorial Prize winner in economics) socialism is "democracy and a classless society." Perhaps we should treat "democracy and a classless society" as a definition of democratic socialism. Then socialism means just a society with only one class, the working class, regardless of the system of government. Certainly there were people who favored a dictatorial socialism, "dictatorship and a classless society." Nicolai Lenin, the founder of the Soviet Union, was one of them. Their idea was that the dictator would be the voice by which the working class would express its government of society. There were also libertarian socialists, that is, people who favored a classless society with the maximum of possible political liberty.[1] Some of the libertarian socialists were anarchists, who wanted a classless society with no government at all. When it is put that way, perhaps the terms "democratic socialist," "libertarian socialist," and "anarchist socialist" may not seem so strange. Is there something about a classless society that requires the existence of a government? The only balanced answer is "maybe." All of these socialist ideas have been controversial from the beginning, and have been critical of one another. For example, the libertarian and democratic socialists often argued that a dictatorship could not co-exist with socialism, since the bureaucracy and political groups surrounding the dictator would eventually form a new exploiting class, and re-establish capitalism with themselves as the capitalists.[2] This is probably what Lewis had in mind when he included democracy in his definition of socialism. The socialists felt that a capitalist society is unavoidably divided between the capitalist employer class and the working class of employees, so a classless society would have a noncapitalist economic system. But this does not tell us just what the non-capitalist economic system would be. There have always been several schools of thought on this, among socialists. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the major theorists of socialism in the 1800's, were careful not to describe a "socialist economic system" (though they clearly had their own opinions of what it was likely to be). Instead, their position was that the economic system of a socialist society should be decided democratically by the workers themselves. Another element in this mix was communism. Originally separate from socialism, the communism saw competition as the root of all evils. In the communist society, the economic rule would be "from each according to his ability, and to each according to his need." But that rule could not be applied in a capitalist society, because of the defective human character capitalism produces. Communists believed that human character is formed by the environment. A competitive environment would cause people to grow up greedy and aggressive. But, in turn, a population of greedy, aggressive people would create a highly competitive society, so that their children, too, would be greedy and aggressive. Thus, the communists saw the social evils of aggression and competition as the result of a vicious circle. To break the vicious circle, the communists felt that the small, intelligent minority who understood this truth should take power as a dictatorship, an "educational dictatorship," and ruthlessly suppress competition, and direct the allocation of resources "from each according to his ability, and to each according to his need." Thus, over a few generations, a new virtuous circle might be set in motion, in which sharing and action on behalf of the whole population would replace greed and aggression as the basis of society and human character.[3] In "The Communist Manifesto," Marx and Engels tried to bring the socialists and communists into a common movement with a common program. To reconcile these quite different ideas, they proposed that socialism -- a classless society -- would be the first stage in a social evolution that would lead to communism as a later and higher stage, without an educational dictatorship. Marx and Engels argued that competition could not be eliminated so long as there is scarcity; but that the socialist society would rapidly increase productivity so that scarcity could be eliminated, and then "from each according to his ability, and to each according to his need" could be the rule. Does this make sense? We should not reject it too hastily. Increasing labor productivity has already transformed society in many ways: just a few generations ago, most human beings were farmers who consumed most of what they consumed, and market capitalism was impossible. Increasing productivity made market capitalism possible. Perhaps it will eventually make communism possible. The reader may judge these ideas, since "The Communist Manifesto" is still in print.[4] Yet another challenge to capitalism came from nationalism. Capitalism arose at the same time as nationalism did, and capitalism could not have come into existence without the national state. But the national state challenged the capitalist system in two ways. On the one hand, some nations lagged behind others, remaining poor and agricultural as other nations industrialized. Some of the relatively poor nations borrowed part of the socialist idea, changing it and applying it not to a division between classes but to a division between nations. The real key division was not between classes but between nations, they said, and the poor nations, the "proletarian nations," had to rely on their national governments rather than on a capitalist economic system to assure their prosperity. This idea led to fascism in the first half of the twentieth century and played an important part in the ideologies of some less-developed countries in the second half of the twentieth century, though (it should be stressed) fascism and the less-developed country ideologies were very different in some important ways. But, second, the national state was seen as a vehicle of economic planning. This idea held that the market economy was unplanned and thus, in some sense, wasteful and misdirected; by contrast, if the national state were to take over direction of the economy, production could be carried out on the basis of a coherent plan. This idea of a centrally planned economy was a very powerful one. It has come to be associated with socialism and with the failure of the Soviet-type systems in the twentieth century, but that identification is hasty in a number of ways. It is true that many socialists, probably a large majority, advocated a centrally planned economic system. They thought central economic planning fit well as the economic system for the first stage of socialism. On the one hand, if the government would direct the economy, there would be just one class -everyone would be government employees. On the other hand, a planned economy might (it seemed) be able to speed the growth of productivity, bringing nearer the transition to communism. But there might be other ways of accomplishing the same things -- we will discuss some of them later in this chapter -- so central planning was not necessary for socialism. Nor was socialism necessary for central planning. A centrally planned economy might keep and even reinforce the distinction between the working and employing classes, and, in fact, that was part of the Fascist idea. In any case, the combination of socialism, communism, and central planning was an idea with great intellectual power in the first half of the twentieth century, and this idea had consequences. Accordingly, we will next explore the pure idea of a centrally planned economy, then look at the real attempts to put central planning into practice in the Soviet-type and Fascist economic systems, and then finish up by looking at some other approaches to constructing a classless socialist society. Central Planning 1 Advocates of central economic planning agreed that the economic plan would be rational, in some sense that market economies are not. The word "rational" can mean many things. Neoclassical economists usually interpret "rational" as meaning "optimal;" that is, a decision is "rational" if it is directed to an objective (or a compromise between two or more objectives) and achieves that objective (or those objectives) to the greatest extent possible. Thus, economists have explored the idea of an "optimal plan." The first step in optimal economic planning, then, is to determine the objective or objectives the plan is to advance. Since there will almost certainly be more than one objective, the central planner will also have to determine how one objective is traded off against another -how the objectives are to be compromised, when they conflict. If the planned society is supposed to be democratic, then these objectives and compromises will be decided by democratic procedures -- otherwise, by the sovereign authority in an authoritarian system. Next, it will be necessary to translate those objectives into quantities of goods and services that will support the objectives to a greater or lesser extent. For example, if health improvement is a highly ranked objective, then a mixture of goods and services that includes more medical care and less chocolate will probably advance the objectives of the planners more than the reverse -- but only up to a point. If production of medical care were to compete with the production of food, resulting in malnutrition, that mix of production would rank low in terms of the health objective, and probably others as well. Notice that this judgment is a technical one. It depends on knowledge of how production of goods and services affects the objectives. This is a question of fact, and not politics; leaving it to politics, however democratic, could only cause confusion. From this point on, most of the decisions to be made in economic planning are like that, technical rather than political. The next step is to determine what goods and services the economic system is capable of producing. An optimal plan is one that achieves the objectives to the greatest possible extent; one thing that limits the possible extent is that the economy can produce only a limited quantity of goods and services. Once again, we express this limit with the production possibility frontier, as in Figure 1 above. This limitation on what can be produced with scarce resources is what forces the plan to compromise between the various objectives the planners might pursue. But the first step for Economia's planning bureau (we recall) is to determine what its objectives are, and to express those in terms of quantities of food and machinery produced. Let's suppose the planning bureau's objectives are expressed by the gray curves in Figure 3. The idea is that every combination of food and machinery expressed by a point on the lowest curve meets the planning bureau's objectives to the same degree, and that is a fairly low degree. Every combination of food and machinery expressed by a point on the highest curve equally meets the planning bureau's objectives to a relatively great degree. Every combination of food and machinery expressed by a point on the middle curve meets the planning bureau's objectives to the same, fair-but-not-great degree. Combinations of food and machinery on a higher curve meet the planning bureau's objectives more completely than those on a lower curve. In brief, the planning bureau wants to place the economy on the highest curve that it can -- and that is what the curves express. The curves are one way to express the planning bureau's objectives in terms of production. (There could be many more curves -- infinitely many). These curves express the Planners' preferences. Figure 3 Visually, the highest curve the Economian economy can get to is the middle one, and to do that the planning bureau has to plan for the production of the combination of food and machinery shown by the *. That is the optimal plan. But how is the planning bureau to move the economy toward that optimal plan? If they simply had all the necessary information, and a very powerful computer, perhaps they could simply tell each farm, workshop and office -that is, each enterprise in the economy -- what to produce and where to ship it. (This is called the double address system -- each directive is addressed to the enterprise that is to produce the good or service and also to the enterprise, perhaps a retail store, that is to receive it). The difficulty is that the planning bureau is not likely to have all the information it needs to do this. It may direct some enterprises to produce much more than they are capable of producing, with the resources supplied, and others to produce much less, so that most of their resources go to waste. In general, the managers of the enterprises will probably have a better estimate of what they can produce than the planning bureau has, and of the resources necessary to produce it. How can the planning bureau function, in such a case? How can they get the information they need? Central Planning 2 Once again, how can the planners get the information they need? One possibility is to ask the enterprise managers how much they can produce. Let's make the optimistic assumption that the enterprise managers will tell the truth -- either because they are nice guys or because the planning bureau has found some costless way of giving them an incentive to tell the truth. The planning bureau could start out by sending the enterprise managers a tentative list of outputs to produce, and ask the enterprise managers how much resources they would need to produce that list. Then add up the resource demands and compare them with the resources available. Adjust the tentative plan accordingly, and try again. Keep trying until the plan is (pretty close to) optimal. Each of these tentative lists of outputs is called an "iteration" of the plan. Figure 4 Figure 4 shows one possible series of iterations of the plan. The bureau starts out optimistically with a tentative plan at A. Looking at the diagram, we know that A is infeasible. That means the enterprises' resource requirements will add up to more resources than are available. Adjusting, the planning bureau follows up with B. That doesn't really help -- B is infeasible, too -- but with the information they have gotten from the enterprises on these two attempts, the plan bureau is able to make its third iteration C. That is an improvement -- C is feasible -- but C is not efficient, since enterprises are capable of producing more than C with available resources. On the next round, then, the planning bureau scales up the production amounts to D. This is better still -- D is efficient, that is, on the production possibility frontier -- but it is not optimal. With the available resources, the planning bureau would prefer to see more machines and less food produced. By now, however, the planning bureau has gotten the information they need, and on the next iteration they move up the production possibility frontier to *, the optimal plan. This is the plan they direct the enterprises to carry out. This is a very optimistic story. There are many pitfalls that could make it difficult to move to an optimal plan, and further problems in making the plan work even if it were optimal. Even if the enterprise managers tell the truth, it might take many costly iterations of the plan to get to the optimum at *. Worse, the enterprise managers have strong incentives to lie and distort their productive potential and resource needs. Suppose that I am an enterprise manager, and I guess wrong, thinking that I can produce 2000 with 500 of resources. In reality, I can only produce 1000. So the planners send me 500 of resources, and an order for 2000 olf output, and when I try to do it, I find I cannot produce what I have been ordered to produce. By the time I have found out, I'm in trouble. On the other hand, if I had lied, telling the planning bureau that I could only produce 500, then the 1000 actual production would leave me in very good shape. I would probably only send in 700 or 800 of my production, hiding the rest in case I should have some problems next year. On the other hand, the planning bureau may have other information. In most cases, they can take it for granted that the quantities produced in earlier years are feasible, and they may be able to use statistical, engineering and computational techniques to fill in the information they don't get from the enterprise managers. Then again, even if the plan is optimal -- by the preferences of the planners -- the consumers may not be very happy with it. If the planning bureau tells the enterprises to produce one finger brush per person, the chances are that the consumers won't buy them all at any price, nor use them even if they are free. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that an optimal planning system might be set up, might be successful, and might improve human life from many points of view. The problems that would have to be overcome are difficult ones, and no-one knows now how to resolve them. But human beings are inventive, creative beings, and it may be that future generations will come up with solutions that we cannot now conceive. Socialism and Planning As we have seen, many socialists saw a planned economy as a means for the economic organization of a classless society. Everyone would be of the same class -- government employees. One of the clearest and most complete proposals along these lines came from the Fabian Socialist Society in Great Britain, under the leadership of Sidney Webb, in the first half of the twentieth century. Webb envisioned a socialist country with a democratic parliament, much like the British one in his time. Once the government had taken over the control of production, the management of enterprises would become part of the civil service. The various branches of production would be organized as "ministries of production," alongside the ministries of education, health, war and so on. For example, there might be a ministry of agriculture, a ministry of mining, a ministry of heavy industry, of computer hardware, of computer software, and so on. The planning bureau would then work rather like a cabinet committee, coordinating the plans of the different ministries of production. That sort of "democratic socialism" has never been tried in an industrialized country. Perhaps, if it had been tried, it might have worked -- though, as we have seen, the obstacles are pretty discouraging, and no doubt that is one reason why it has never been tried. However, the Soviet Union adopted a system based on it, roughly from 1930 to 1989. The Soviet Union had come into existence in the Revolution of 1917 that destroyed the Russian Empire. Nicolai Lenin (aka Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov) made himself its dictator and was succeeded by Joseph Stalin. Under Lenin's government there were a series of experiments in economic organization; but Stalin adopted something like the system Webb had proposed. The Soviet legislature was not the democratic parliament that Webb had in mind -- although at one point Webb managed to persuade himself that it was close enough. However, in the context of a dictatorial political system, the Soviet Union did organize its different branches of production into ministries, making the managers part of the governmental "apparatus." They did also adopt a system of planning that involved tentative plans and repeated iterations, along the lines described in the last system. (In fact, that discussion was suggested partly by the historical Soviet planning system.) However, they never really tried to get to an optimal plan. Indeed, they don't even seem to have tried to make the plan efficient. In terms of Figure 3, if they got to a feasible plan -- something like point C -- there was little effort to move to an efficient point like D, and no effort to get to an optimal plan like *. It is not clear that the Soviet planners even understood the concept. We should keep in mind that, at the beginning of the Soviet planning system, there were no computers. The Soviet civil service and business management were backward, even by noncomputerized standards. In its earlier period, the Soviet government was quite terroristic, and in the later period corruption became the major factor in the economy. For these reasons, some may judge that the Soviet experiment was not a fair trial of the ideal of economic planning. Some very fine American neoclassical economists have believed that a highly computerized late twentieth century industrialized economy could make planning work, even though the Soviet Union could not. All the same, it has yet to be demonstrated. More "Planners" Fascism Fascist political systems were not designed to create a classless society, but a new class system, a "new order," with the fascists themselves (of course!) at the top. Fascists claimed that class differences were not important, but that the important struggles and exploitation were relationships among nations. Some nations were "proletarian nations," exploited by other nations, because of historical accidents or of treachery by some part of their own populations. But a superior nation, with a strong, absolute leader and with a great revolutionary act of will, could reverse that, making itself a new national ruling class over its former oppressors and over the whole world. This would be the "new order." What reason might an "oppressed nation" have to think that it might really be possible to conquer its neighbors and oppress them in turn? In the 1920's and 1930's, the Fascist nations found historical precedents to convince themselves. For Japanese fascism, the precedent was relatively recent. Only a few hundred years before, their neighbors the Manchu people had made themselves the rulers of China -- that is, all of the world that really mattered from the Manchu point of view in 1600. For Italian fascism, there was the Roman Empire. The ancestors of the Italians themselves had, two millennia before, dominated (almost) all of the world they could reach. For the Germans, the case was more difficult. Their ancestors had once overcome half of the Roman Empire (but then divided among themselves and given most of it up to others) and, a few hundred years later, German knights had dominated many of their neighbors. But that is thin stuff, so the German Fascists claimed that the Germans were really Aryans, who had (they supposed) conquered pretty much everything, just a few thousand years ago. This idea that the clock could be turned back to a time when Our Nation Ruled the World was an important part of Fascism. Fascists were contemptuous of profit motives, and aimed to subordinate all other purposes (including profit) to the national objectives of victory over other nations. Thus, they rejected market systems in principle, and officially established "planned economies." In practice, they fell even further short of "optimal planning" than the Soviets. (Since the Fascist powers were able to survive for only about 20 years before being conquered by the Soviets and the democracies, perhaps they just didn't have time to get it working). Although terroristic, their "economic planning" was, at the same time, disastrously corrupt. Far from subordinating the profit motive to national purposes, the Fascist system seems in practice to have subordinated terroristic national government to the corrupt profit motives of the Fascist party leaders. This so weakened the Fascist nations that they were defeated despite having very good armies in some cases. It is hard to say this -- given the evil that Fascism has done in this century -- but perhaps we can conceive a Fascist system that would not be avoidably oppressive, terroristic, or warlike. Perhaps we can conceive of an upper class distinguished mainly by its support for traditions that a large majority support. (For myself, I don't believe it is possible, but let us set my doubts, and perhaps yours, aside). It makes sense that a government of this kind would not rely on the untraditional forces of the market to control production. It might adopt a system of central economic planning, with objectives based on its traditionalist views. Like a hypothetical future socialist system, it might even make central planning work, in the service of a class-based and antisocialist ideal. Many things are possible. Time may tell. Emerging Nations The most dynamic Fascist governments were destroyed by their defeat in World War II. After World War II, the colonial governments of many countries of Africa and South Asia were eliminated. These countries, and the poorer Latin and Caribbean countries of the Western Hemisphere, often saw themselves as the victims of exploitation by other countries -- and their colonial history gave them some reason for that view. Many of these "emerging nations" moved toward a considerable degree of government control of the economy and planning. Many called their system "socialist." In practice, their planning tended to be patterned after that of the Soviet Union, but large parts of the economy remained outside both the plan and the market. Also, some of the governments were far more democratic than the Soviet Union, and even those that were not much more democratic were less powerful. On the other hand, they were even less prepared than the Soviet Union had been for the technicalities of optimal planning. More recently, market-oriented systems in less developed countries have been more successful, and, following that example, socialist "emerging nations" have tended to move toward market systems. Market Socialism After the beginnings of the twentieth century, neoclassical economics became better known, and socialists such as the Polish Marxist Oscar Lange were aware of the theory that market equilibrium could lead to an efficient allocation of resources. If planning should prove too difficult (they argued), a government-controlled economy could be run according to the same principles of supply and demand. Remember, for the socialists (not the communists) the main thing about government ownership of enterprises was that it was a way of organizing a classless society. Enterprises should be owned by the government, not by a class of capitalist employers; and everyone should be an employee. But this does not quite mean that the economy is directed by the government. In a "market socialist" society, enterprises would be owned by the government, but independently run by appointed managers. The managers would be instructed to direct the enterprises in such a way as to maximize profits, at market prices, as (in theory) the directors of capitalist enterprises do. Thus, the various enterprises would adjust their production to an equilibrium of supply and demand. The allocation of resources would be efficient, as in the ideal market capitalist system. Since the profits would revert to the government, as owner, they could be distributed to the poor (or to everybody) as a "social dividend." Thus, a market socialist society would be an efficient, classless market society with a lower limit on income and thus no extreme poverty. This is a very appealing ideal from the viewpoint of neoclassical economics. A few neoclassical economists, driven by logic rather than socialist convictions, endorsed market socialism as simply a superior economic system. However, as with all the ideals, there may be problems in practice. Problems of Market Socialism A system of independently managed government-owned enterprises maximizing profits at market prices would run into some of the same problems that market capitalism would. Like market capitalism, the values it would realize would be consumer preferences, not other kinds of values that some may feel are "higher." Monopoly and externality could also be problems, and perhaps "Keynesian" failures to employ the labor force might occur. Thus, in practice it would be necessary for a market socialist society (like a market capitalist society) to mix in a good deal of government control of the economy. On the other hand, centrally planned economies always had some markets. Thus, it might be hard, in practice, to find the boundary between real market socialism and real government-controlled socialism. During its period of communist government, the Hungarian Republic adopted reforms that made it a fair approximation to "market socialism," and the criticisms of market socialism in Hungary suggest a more general obstacle to market socialism. The technical term is "soft budget constraints." The meaning is simpler than the term. If a government-owned enterprise should overspend its budget and lose money, what would happen? In practice, government would not allow the enterprise to fail, but would instead "prop it up" with subsidies and "bail it out" with more wasteful government capital investments. Thus, government-owned enterprises that really should be liquidated would never be liquidated, but would continue to exist, eating up government subsidies. Perhaps even worse, enterprises that could shape up and improve their efficiency would have no incentive to do so. As long as you can fall back on government subsidies to make up losses, why go to the trouble to improve efficiency? (After all, one way to increase in labor productivity is to eliminate your job). But soft budget constraints are not a market socialist exclusive. Despite the abolition of communism in eastern Europe, "soft budget constraints" are still a problem there, according to many of the pro-market economic reformers. And, indeed, governments have been known to "bail out" enterprises with government investment and to "prop up" losing enterprises with subsidies even in countries which have never been socialist in any sense. Here in the United States, some losing Savings and Loan Companies were "bailed out" with government investments in the 1980's, and some of the beneficiaries were the relatives of prominent politicians of both major parties. The problem seems to arise unless the control of enterprises is distinctly separated from the control of government. When the government owns the enterprises, or the owners of enterprises control the government, "soft budget constraints" become a problem. However, it is plausible that a real-world "market socialist" system would be especially vulnerable to the "soft budget constraint" problem, since the enterprise is government owned, the manager a political employee, and a separation between the control of enterprises and the control of government is especially difficult to establish. Labor-Management 1 Before the Russian Revolution in 1917, there were a number of schools of thought in socialism, as we have seen. Some were opposed to government control of the economy, and some were opposed to the existence of government at all -- they were anarchists. Thus, they opposed government control of the economy, and opposed economic planning in that sense. Instead, they proposed that the economy should be controlled by the working people themselves, in the individual workshops, factories, and offices. Their idea was that each place of employment should be a little democratic republic, with the employees electing the bosses and determining the basic policies of the enterprise by majority voting. In the twentieth century, the ideal of a market economy with labor managed enterprises has been followed by one country, Yugoslavia, and has been advocated by some economists and others. We may think of labor-management as a form of market socialism, with the difference that, rather than being managed by government appointees directed to maximize profits at market prices, labor-managed enterprise would be managed by a person elected by the employees and directed to manage the enterprise in their interests. Ideally, then, the control of enterprises is distinct from the control of government, and we might hope that "soft budget constraints" might not be so much of a problem. While Yugoslavia is the only country that has ever attempted to base its economic system on labor-managed enterprises, many labor-managed "cooperative" enterprises have existed in generally capitalist countries, and they have been successful in many cases. Some also existed in Soviet-type economies. In the German Federal Republic, some large enterprises have been required for generations to allow the employees to elect one-third to one-half of the members of their boards of directors, introducing a democratic element into the operation of capitalist corporations. This, too, has been successful. So there is a good deal of experience in the operation of democratic enterprises, in and of themselves, and the proposal that enterprises could be run democratically is by no means visionary. But who would "own" labor-managed enterprises? If the system is to be socialist, then they cannot be owned by a capitalist class. Most advocates of a socialist system with democratic firms would say that the enterprises themselves, and their machinery and factories and workshops, should be "social property," the property of society. But what does that mean? One possibility is that the enterprises could be the property of the state, with the state acting as the agent of society. This comes even closer to market socialism, but it also poses the question of keeping the control of enterprises clearly separated from the control of government and eliminating "soft budget constraints." An alternative approach to "social property" has been suggested in these pages, but it is untried in practice. In the alternative approach, organizations such as workers' pension funds and endowment funds for socially useful activities such as free hospitals and fire protection would be recognized as agents of society and could be owners of social property. But "what could social property mean?" will have to remain an open question for now. Labor-Management 2 What can we say about efficiency in a labor-managed socialist market economy? Beginning in the late 1950's, a number of economists explored that question. As in the neoclassical theory of capitalism, they began from the assumption that the enterprise would maximize something. If it is managed in the interest of the employees, the enterprise would not maximize profits, but it might maximize income per employee. That is the assumption with which we begin. Next, we make the usual assumptions of "perfect competition:" all inputs and outputs are homogenous, including labor, and prices of all goods and services are determined by supply and demand. Wages are not determined by supply and demand, however -- the enterprise' wage is simply its average sales revenue per worker. Figure 5 We can visualize the difference between an ideal labor-managed enterprise and an ideal market capitalist enterprise in Figure 5. The downward sloping line VMP is the value of the marginal product curve -- the price of output times the marginal product of labor. The curve AR is the average sales revenue per employee, excluding the costs of inputs other than labor - the price of output times the average productivity of labor, net of the fixed costs of production. The line OC is the opportunity cost of labor -- the market value of the marginal product of labor in other industries. Thus, in an ideal market capitalist system, OC is the wage, and the enterprise would employ N2 units of labor. By contrast, the labor-managed enterprise will employ only N1, since income per employee is largest with N1. This is inefficient. There has been a good deal of controversy about this analysis, but what it seems fair to say is this: in at least some circumstances, a labor-managed enterprise would have a motivation to restrict its hiring to a work force smaller than the efficient size. This applies only in the short run. We know that this result would not be stable in the long run, in an ideal market capitalism, since the enterprise is making an economic profit. That is, there is revenue in excess of the labor cost and also in excess of the nonhuman costs (because of the way the curve AR was constructed). Therefore, with free entry, more companies will enter this industry and compete for some of those profits. So the price will drop, and the AR will shift downward until we have the situation shown in Figure 6: Figure 6 What we see in Figure 6 is that, in a long-run equilibrium, the capitalist firm and the labormanaged enterprise employ the same labor force, N1. Since we know this is efficient, we see that the labor-managed enterprise, like the market capitalist enterprise, is efficient in long-run equilibrium. Problems of Labor-Management In comparing ideals, then, we may say that the labor-managed enterprise may be somewhat less efficient in the short run, but equally efficient in the long run. But there are practical difficulties on both sides. In the labor-managed enterprise, we may have higher labor productivity because the employees feel they are "working for themselves." Many economists have expressed skepticism about that, but a mind as great as that of John Stuart Mill accepted it. In any case, it is a question to be decided by the evidence, and the evidence is that labormanaged enterprises do attain higher labor productivity than capitalist-owned (or governmentowned) enterprises in comparable circumstances. Thus the inefficient labor-managed enterprise may actually produce more than the efficient capitalist enterprise! (With more output per worker, a smaller work force might produce a larger output). This is not shown in the diagrams, of course. On the other hand, the actual labor-managed enterprise may do less well than the ideal one in the long run. Long run equilibrium comes about through free entry. The ideal labor-managed economy would have free entry, in that new enterprises may be set up to compete for the wages above the opportunity cost that we see in Figure 5. But a labormanaged enterprise is a bit more complicated than a capitalist firm, and so it could be more difficult to set them up. Thus, we have to worry about whether enough new labor managed enterprises will be set up to bring the labor-managed economy into long run equilibrium. In addition to these practical difficulties, a labor-managed market economy would face the problems of any market economy: What some see as the tawdry values of the marketplace, monopoly and externality, and possibly "Keynesian" unemployment. In addition, the unclarity of the concept of social property has been a crucial difficulty. Yugoslavia, which had labormanaged enterprises for several decades beginning in the 1950's, never really decided this issue. At the beginning, the government was the owner as the agent of society. Later on, attempts were made to modify this, but no-one ever really knew what the rules of the game were. The Collapse of Communism After 1989, the Soviet Union and the other European countries with "planned" economies (that is, the Soviet-Type Economies) experienced a period of troubles of various kinds, and largely abandoned both the planned economy and the aims that define socialism and communism. It seems to be widely believed that this proves that a planned economy cannot succeed. However, a careful look at the evidence suggests that this view is oversimple. Figure 7 below shows the economic performance of four groups of countries for 1960-1989, the generation just before the collapse of the Soviet-type countries. Each curve shows gross domestic product per person (GDP per capita), adjusted for inflation and international differences in purchasing power, as a proportion of the country's gross domestic product per capita in 1960. Thus, they all begin at one in 1960 and rise as the country's GDP per capita increases relative to the starting point. These data are taken from the Penn World Tables and represent the best estimates of production from the neoclassical economic point of view. The red line shows the average for four countries with Communist governments : the USSR, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia.[5] These are the only four for which the Penn World Tables have data for the full period. The blue line shows the average for four very successful industrialized capitalist countries: the U.S.A, West Germany, Japan and Britain. We see that, by the standard of economic growth, the Soviet-type countries did better than the capitalist ones. On the whole, the Soviet-type countries increased their GDP per person by 3.3 times, while the capitalist countries increased their performance by 2.74 times. If the cause of the collapse of the Soviet-type countries was their economic performance, we might suppose that the capitalist countries would have collapsed too; but they did not. The green line shows the performance of the "four tigers:" South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. Their performance is clearly a good deal better than the others -- they doubled the growth of the Soviet-type countries (actually growing 2.08 times as much in the period) and much more than doubled the performance of the four large capitalist countries (growing 2.61 times as much in the period). This group of countries, however, was very unusual. Two (Hong Kong and Singapore) were city-states. Had they included the surrounding agricultural regions, they would not have done as well. The other two were the beneficiaries of very large amounts of American economic and political assistance. This is not to detract from their performance. They were among the most successful countries in the world -- thus not representative of either capitalist or Soviet-type countries. The magenta line at the bottom shows the average growth performance for four lessdeveloped countries: Algeria, Zaire, Brazil, and Indonesia. This group includes one of the worst performers in the world: Zaire. However, 1) even without Zaire, the other three countries do not quite double their per capita income over the period, coming in solidly last, and 2) Brazil and Indonesia are strong performers, for their group, that have been mentioned as emerging industrial countries in the 1990's. Over the period, Algeria did about as well as Indonesia did. Thus, except for Zaire, these countries would hardly be considered economic failures, by the standards of less-developed countries. But the Soviet-type countries easily tripled the performance of the LDC's, with or without Zaire. Figure 7 This does not really disprove the view that the planned economies were economic failures. A more careful examination of the evidence might show up a different kind of evidence that could support that view. But there is another hypothesis about their collapse that fits this (and other) evidence better: that the collapse of the communist countries was a result of the failure of their political systems, and that it was political failure that caused the economic problems, and not vice versa. Indeed, why would this be a surprise? Absolute and totalitarian governments have been collapsing throughout the twentieth century. The great lesson of the twentieth century is that, in modern conditions, democracies endure and authoritarian governments eventually fail. However, it does seem that a political collapse can cause even greater problems when the economy is planned than when it is a market economy. This is a major weakness of economic planning. The key fact is that the Communist countries did fail, and they failed in several different ways: The overall statistics conceal the fact that some kinds of production were very unsuccessful. For example, agriculture in the Soviet-type countries clearly failed, and failed because of the collective and state farms and nonmarket systems the government imposed on the farmers. Ironically, it is agriculture that has remained least affected by the so-called market reforms of the 1990's, and agriculture is still dismally unsuccessful in the post-Soviet countries. (The Chinese People's Republic, more wisely, began its market reforms by turning agriculture over to the farmers, and this smart move gave them the boom they have enjoyed in the generation since.) Similarly, the collapse of human services, such as health and child welfare, in the Soviet republics and Romania is notorious. They failed as planned economies. As we have seen, the Communist countries never really tried to put an optimal plan into effect. In addition, neoclassical economics tells us that there are some problems that a planned economy could do better with than a market economy. These are problems based on externalities -- which includes environmental problems. But the Soviet-Type economies did even worse on these problems than the market economies did. They failed as socialists. Just as the critics of "socialist dictatorship" predicted, the political groups associated with the dictatorship became a new exploiting class and reintroduced capitalism, with "privatization programs" designed to make themselves the new capitalists. But, in the Russian Republic, they found the gangsters had gotten there before them. The struggle between the former Communists and the gangsters for control of the Russian economy has not yet been decided.[6] They failed as communists, since their dictatorship did not eliminate competition, but replaced market competition with bureaucratic competition, which is at least as bad. There is no evidence that they were setting the stage for a new generation that had learned not to be greedy and aggressive, and, if anything, it appears that they had done just the contrary -- taught their leaders to be even greedier and more aggressive than capitalists are! Thus, while it is not so clear that the planned economies failed in terms of neoclassical economics, it is quite clear that they failed according to their own values -- and this seems to be the most important thing. Summary Of all the ideal systems that have engaged the attention of political movements during the twentieth century, it seems the ideal of a government controlled and centrally planned economic system has been the most influential and the least successful. Market systems have been predominant in most of the world, but the ideal of a market system has become politically dominant only late in the century. The collapse of totalitarian governments in countries with central planning has been widely blamed on the inadequate performance of central planning, but this seems a hasty judgment. The timing is wrong. The centrally planned countries had economic problems from the start, in fields such as agriculture, and their performance deteriorated steadily in some other areas; but despite this they were able to keep up economic growth at a more rapid rate than the capitalist and less developed nations until the collapse of their political systems. It was this political collapse that caused their transformation, and it came about because the ruling groups themselves lost confidence in the political system they led. But a more detailed look at the performance of these countries is not encouraging. They did fail in many ways, long before their political collapse. The character of these failures may not be especially important from a neoclassical point of view. From that point of view, a high rate of economic growth can redeem most other shortcomings. But from the point of view of the values that led socialists to support economic planning, the failures of the Soviet-type economies were damning. They did not support human services and substitute human values for the tawdry values of the marketplace. They did not build socialism nor communism. They simply made themselves the new exploiting class, and, finally, the new capitalist class. And even that they have done badly, so far. The other practitioners of economic planning, the fascists and "socialist" emerging nations, did even worse from the neoclassical point of view. So, while we must admit that some future society may make an all-around success of economic planning, since it is hard to judge what may happen hundreds and thousands of years in the future, there is good reason to doubt that people now living will see successful economic planning. The other ideal systems, market socialism and labor management, have been given less complete trials. By the same token, they remain somewhat abstract and incomplete in their conception. If we are to see successful systems of market socialism or labor management or some combination of both in the future, there are still details to be worked out. How can enterprises be government-owned and the government not "bail them out" with subsidies if they fail? And if labor-managed enterprises are not to be government-owned, who shall own them? What can "social property" mean? For those who want to see a class-less society, those will be difficult problems to solve, requiring a good deal of thought, trial and error. For those who see no need for a class-less society, they will seem to be fatal flaws in socialist thinking. Time will tell the answer, and perhaps some of us will live to see it.