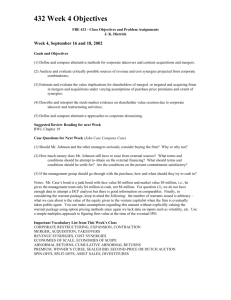

sirower [synergy] - Columbia Business School

advertisement

![sirower [synergy] - Columbia Business School](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008625403_1-88832097b24e6e902e25af41e21ba254-768x994.png)