Online Tutorials - New Jersey Library Association

advertisement

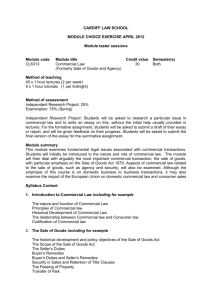

Information Literacy Online Tutorials: An Introduction to Rationale and Technological Tools in Tutorial Creation 1. Introduction Library instruction has been an important part of academic librarianship. With proliferation of information resources and complexity of search skills, students and faculty are dazzled by the difficulty in identifying the right resources in their research. Library instruction has become a required component in undergraduate curricula in many academic and research institutes. As early as in 2000 the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) published its Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. According to the ACRL (2000), “Information Literacy is the set of skills needed to find, retrieve, analyze, and use information.” It is “a key component of, and contributor to, lifelong learning.” Several accreditation agencies consider information literacy as a key factor for students such as the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE), the Western Association of Schools and College (WASC), and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). Like any faculty members, we librarians go to classrooms regularly and teach students how to identify information sources and do research. Traditional library instruction has been incorporated into curricula. Librarians have been recognized as teaching faculty. Then suddenly one day we woke up and found ourselves facing the challenge of online courses. Just in the last two years colleges and universities have increased their online courses by 15% to 20%. According to the 2007 Sloan Survey of Online Learning (Stover, 2007): “The enrollment in online learning has increased at a rate of 21.5 percent over the past five years. The survey also found that almost one in five higher education students currently takes at least one class online.” This is a new challenge. Traditional in-classroom library instruction does not fit in with the model of online long distance learning. The latter is precisely the kind of instruction that many colleges and universities have increased over the past several years. The only way to face the challenge is to create online library instruction tutorials and incorporate the library component into online courses. Librarians understand that developing online tutorials is the first step towards integrating library instruction into university’s online courses. The question is how? This article will examine the types of technologies academic libraries that have been used in creating their online tutorials. A discussion will follow on the adequacy of current practice in tutorial creation. We will introduce the readers to some of the useful tools for developing state-of-the-art and successful online tutorials. Learning technological-know-how is a must in modern academic librarianship. 2. Literature Review “Web-based library instruction requires more than duplicating print instructional materials on the web. Good online information tutorials should effectively incorporate multiple instructional media into the web presence to convey the instruction in multi-stimulating ways (Zhang, 2006)." A review of the literature on information literacy online tutorials shows a genuine consensus among academic librarians that the first generation of library online tutorials written solely in HTML is outdated. Such tutorials are described as "long, linear, and full of as many skills as possible (Pressley, 2008)." Lamb and Johnson (2008) voiced their dissatisfaction with "static web pages" vs. “web presence” in online tutorials. There was a call at the 2007 ALA Midwinter meeting for librarians to "move on from stale, barely interactive tutorials of the 1990s (Brown et al., 2007)." Many authors agree that academic libraries face a new generation of student clientele, the Generation M (M stands for Media). “Today's students have grown up in an information environment very different from the one that many of us remember. They have been raised on the fast-paced edutainment of Sesame Street and have spent their adolescence watching 3-minute music videos on MTV. Their media environment specializes in short messages and multimedia, with news dispatched in sound bites and snippets of stories (Pressley 2008).” A survey conducted in 2002 (Jones, 2002) shows that "students entering our institutions to be Internet natives eager to collaborate and interact virtually (Brown et al., 2007)." When creating library online information literacy tutorials, the challenge is to meet the learning needs of the Generation M students. One way to do this is to create a familiar learning environment for the digital savvy students. A study by Armstrong and Georgas (2006) was conducted to measure the effectiveness of interactive online tutorials among undergraduate students. The outcome showed that "Students responded positively to the interactivity and gamelike nature of the tutorial. The high degree of interactivity and the game-like quality of the tutorial are key factors in its success (Armstrong & Georgas, 2006)." In addition to contents, interactivity, multimedia, and game-like quality are identified as essential components in an effective online tutorial. According to the ACRL Instructional Technologies Committee (2008), "Web tutorials should include interactive exercises such as simulations or quizzes." The same view is shared among many other authors. For instance, as Anderson (2008) wrote: "These activities encourage active learning and allow students to respond to what is taught, while self assessing their own learning. Web tutorials should also provide a way to contact a librarian for questions or to give feedback about the tutorial’s design or usefulness." 3. Status Quo Many college and university libraries have developed or are considering developing online tutorials. A literature search indicated that there are no statistics as to what percentage of academic and research libraries have done so. There is a lack of studies in this area. In order to get some basic information about the current practice of online tutorial creation, the author used a random number generator (Haahr, 2008) to get a random selection of one hundred colleges and universities from the Peterson’s FourYear Colleges 2008. The colleges and universities in the sample are in the United States and Canada and their sizes vary with the number of undergraduate students ranging from 30 to 35,110. In the sample, the author examined a total of 372 online information literacy tutorials from the library web sites of the academic institutions. The findings indicate that about 33% of the surveyed libraries have developed their own online tutorials. About 11% have links to online tutorials created by other libraries or database vendors. About 49% of the surveyed libraries have library instruction presence on the web. To describe their teaching programs or online tutorials, about 17% of the libraries in the sample used the term "information literacy" rather than "library instruction". The detailed breakdown of the tutorials based on content type and technologies are as follows. a. Tutorials based on Content type Based on contents, online tutorials created by librarians can be divided into several types. The following table is a breakdown of the 372 tutorials in the survey by content type, with examples taken from tutorials on the library web sites. Table 1. Tutorials Based on Content Type Type Database Search Skills General Introductory Subject Research Library related Concepts or procedures Library related Applications Number of Tutorials 149 119 53 34 17 Percentage Examples 40% Academic Search Premier ABI/Inform Complete 32% Library Research Skills Find Books at EKU Libraries 14% Nursing Research Find Biology Resources 9% Plagiarism Copyright Laws Publish or Perish 5% EndNotes RefWorks Microsoft Word Logging in from Off Campus Total 372 100% 1. Tutorials on a specific database (40%). Most library tutorials found on the web fall into this category. Databases from different vendors may be very different in search features and data presentation. The tutorial on a specific database teaches people how to retrieve and manipulate data in that database. They are more popular and useful than general and subject tutorials. This kind of tutorials may even be useful at reference desk when a reference librarian is busy. The librarian may steer the users to a well-designed and concise tutorial to learn database searching while he or she is busy serving other patrons. 2. General and introductory tutorials (32%). These give a general overview of library resources and teach basic search skills, for instance, by using Boolean operators in constructing a search statement or evaluating Internet resources. General or introductory tutorials are neither very popular nor effective as other types of tutorials, but they are necessary. Such tutorials are not tied to any subject or class assignments. Students do not feel compelled to take them unless they are required to do so. 3. Tutorials of subject research (14%). These teach students of a specific class or major to research resources in his or her subject area such as marketing, chemistry, or psychology. These kinds of tutorials are more popular and practical because students use them when driven by the need for completion of class assignments. They are also useful for faculty pursuing research interests in a subject area. 4. Tutorials on library related concepts, procedures or policies (9%). The best example is a tutorial that explains the basics of complex copyright laws and fair use. Other examples may include plagiarism, term papers, and citing references. Reference desk frequently asked questions are potential contents for a good online tutorial of this type. 5. Tutorials on an application or software (5%). Such tutorials often include Endnote, Refworks, and computer programs. Sometimes they may or may not be related to library functions. For instance, it is often the responsibility of the institution’s Office of Information Technology to teach how to use a computer application such as Microsoft Office Suite. Nevertheless some libraries have tutorials of this nature on their web sites. b. Tutorials Based on Technological Approaches To create their online tutorials, academic librarians have used a variety of technological approaches. The following is a breakdown of the 372 tutorials based on technologies with which they are created. As libraries can develop the same tutorials with several technologies, one tutorial may take on multiple formats. For instance, a library may create the same tutorials in PDF, HTML, and Microsoft PowerPoint and display them on the web for users to choose. Therefore the total number of the tutorial in the table is large from the total number of tutorials in the survey. Six links were found broken in the survey. All of them pointed to tutorials on remote web sites. Table 2. Tutorials Based on Technologies Technologies Tutorial Software/Flash HTML PDF MS PowerPoint HTML with CGI Scripts WMV Video WebCT TILT MP3 Podcast Unknown (broken links) Total Number of Tutorials 132 97 68 33 29 10 7 7 6 1 6 396 Percentage 33% 25% 17% 8.3% 7.3% 2.5% 1.8% 1.8% 1.5% 0.3% 1.5% 100% 4. Technological Tools for Web-based Tutorials a. HTML HTML stands for Hypertext Markup Language. It is a simple and basic language commonly used in creating web pages from1990s. About 25% of the total tutorials surveyed are HTML-only tutorials. HTML-only tutorials can be created by amateurs using Microsoft Front Page or Dreamweaver. However, HTML is not capable of animation and interactivity, features that are helpful in engaging students in elearning. HTML-only tutorials are often reproductions of printed teaching materials. These tutorials may be well-designed and some may have layouts that are stunningly beautiful, but due to their lack of actions, such tutorials can be boring and tedious, especially they are not best suited to the needs of the new digital savvy Generation M. According to Armstrong and Georgas (2006), game-like nature and interactivity in a tutorial are the key factors in the success of an online tutorial. Therefore HTML by itself is not ideal in creating tutorials. An HTML tutorial can be greatly enhanced by CGI scripts. The following are some information literacy tutorials created in HTML: UC Berkeley Library-Finding Information on the Internet: A Tutorial http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/TeachingLib/Guides/Internet/FindInfo.html Cornell University-Library Guide to Library Research at Cornell: Seven Steps to Effective Library Research http://www.library.cornell.edu/olinuris/ref/research/tutorial.html University System of Georgia-Online Library Learning Center http://www.usg.edu/galileo/skills/ b. HTML with CGI Scripts CGI stands for Common Gateway Interface. A CGI script is a small program written in a language such as Perl, Tcl, C or C++, and it functions as the glue between HTML pages and other programs on the Web server (Course Technology, 2008). Some CGI scripts perform the function of transferring data between HTML pages and a web application. Some are used to enhance and make HTML coded pages interactive, dynamic, and lively. About 7.3% surveyed libraries used a combination of HTML and CGI scripts for tutorials. Below are some of the examples of online tutorials written in HTML with CGI scripts. Rider Information Literacy Search Skills Tutorial http://abaris.rider.edu/tutorial1 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library Research Tutorial http://www.lib.unc.edu/instruct/tutorial/ American University Library's Information Literacy Tutorial http://www.library.american.edu/tutorial/index.html Healey Library Information Literacy Tutorial http://www.lib.umb.edu/newtutorial/ Minneapolis Community & Technical College Library Tutorial http://www.minneapolis.edu/Library/tutorials/infolit/ Many web sites provide free CGI scripts written by anonymous programmers for downloading. They are accompanied by live demos and simple instructions for amateurs. The scripts are generally organized into categories by function. One can find CGI scripts that perform almost any functions on the web. For instance, some web sites contain scripts of interactive quizzes that one can incorporate into the online tutorials for end session exams. Other scripts include search engines, pop-up windows, flying banners, twinkling stars, etc. One does not have to know how to write CGI scripts in order to deploy them in the tutorials. Most CGI scripts do not need server access or installation. All one needs is some patience and a little courage to try new things. The following is a list of resources for librarians to get free CGI scripts on the Internet. It involves cut and paste CGI codes into header and body parts of HTML pages. In most cases instructions for using them are simple and clear. CGIScripts.directory.com: http://www.cgiscript-directory.com/ CGI Resource Index: http://cgi.resourceindex.com/ Free CGI Scripts: http://www.free-cgi.com/freecgi/hosting/index.php FTLS.org-Free CGI Archives: http://www.ftls.org/en/examples/cgi/ HotScripts.com: http://www.hotscripts.com/ Krystyna’s CGI Scripts for Educators: http://www.tesol.net/scripts/scriptsdetails.html Matt’s Script Archive: http://www.scriptarchive.com/ Scriptsearch.com: http://www.scriptsearch.com c. E-learning or Tutorial Software While CGI scripts improves HTML tutorials by adding limited animation and interactivity, very few provide the capabilities of audio and multimedia like elearning or tutorial software do. In the last several years many e-learning tutorial software packages have became available. Most are commercial and a few are free with open source licenses. All of them work in a very similar fashion. They can capture mouse movements on the screen and attach sound when editing. Some also include interactive quiz functions. The end products are Flash files with audio, video, and interactivity. HTML and CGI script are not capable to produce these effects. In order to view a tutorial in Flash format, one needs a Flash plug-in for the browser. The Flash plug-in can be downloaded for free at Adobe Flash Player Download Center at http://www.adobe.com/products/flashplayer/. Most Internet users have already got Flash on their computers. Tutorials in Flash sometimes are referred to as videos because they look and feel like videos. When viewed on the Internet, they load effortlessly into a browser like regular web pages. Flash tutorials are really well suited for live demonstrations, especially for creating tutorials of database search skills. It is not easy to use Flash technology to develop subject search tutorials, which generally require comprehensive coverage of resources in a subject area. When used to teach database search skills, Flash tutorials are best if the teaching will be divided into short episodes, each one lasting no more than five minutes. The tutorial software packages are designed for technological amateurs. Some tutorial packages are capable of true interactivity. Librarians can create tutorials single-handedly on their own. As the survey shows, Flash is the most popular format (33%) used by librarians for tutorial creation. The following is a list of e-learning or tutorial software. Once one learns how to use the software, it does not take very much time to create a tutorial. With price ranging from $150 to $600, the software is not too expensive. The following is a list of tutorial software that librarians may use: Commercial Software ViewletBuilder5 at http://www.qarbon.com/ Demo Builder 6 at http://www.demo-builder.com/index.html Adobe Captivate 3 (Macromedia Captive) at http://www.adobe.com/products/captivate/ Camtasia Studio 5 at http://www.techsmith.com/ SWiSH Max 2 at http://www.swishzone.com/ Open Source tutorial software Wink at http://www.debugmode.com/wink/ A Total of 63 Free & Open Source E-learning Software are listed at the following UNESCO site: http://www.unesco.org/cgibin/webworld/portal_freesoftware/cgi/page.cgi?d=1&g=Software/Courseware_To ols/index.shtml The following are some of the libraries that have used tutorial software to create online library instruction: Washington State University (ViewBuilder) http://www.wsulibs.wsu.edu/electric/search/category_results.asp?loc=tutorials&c at=Instructional+Viewlets Babson College (Camtasia) http://www3.babson.edu/library/tutorials/Proquest/proquest.html University of Nebraska Medical Center (ViewBuilder) http://webmedia.unmc.edu/library/medline/medlinebasic_viewlet_swf.html Pennsylvania State University (ViewBuilder) http://aect.ed.psu.edu/viewlets/prerequisite.htm Trinity Western University Library (Wink) http://www.acts.twu.ca/lbr/AcSePr.htm d. Prepackaged tutorials Prepackaged tutorials combine contents and computer programming into one package. Generally they are created by the IT department of an academic institution and later made available to others as an open source program. They have to be downloaded and installed as a package. It takes some technical expertise to customize them for local needs. It also requires some technical skills to install them in a server. There are some nice prepackaged tutorials on the Internet. The most famous and widely adapted one is TILT-Taxes Information Literacy Tutorial at http://tilt.lib.utsystem.edu/. The other examples of prepackaged tutorials include University of Glasgow Study Skills Tutorial at http://www.lib.gla.ac.uk/Training/tilt/studyskills.shtml and Acadia University Library: plagiarism at http://library.acadiau.ca/tutorials/plagiarism/. e. PDF and Microsoft PowerPoint Some academic libraries have used PDF (17%), and Microsoft PowerPoint (8.3%) as their formats in creating online tutorials. In spite of their informative and well-written contents, these tutorials are not very interactive and game-like. They represent printed materials on the web. Even though PDF and PowerPoint are not the best suited tools for creating online tutorials, they are easy to create. Word documents can be easily converted into PDF format by a free converter called CutePDF Writer at http://www.cutepdf.com/Products/CutePDF/writer.asp. For libraries with little technical expertise, these tools are their best solutions. Nevertheless these tutorials should be discarded and replaced by more interactive Flash tutorials. f. WebCT, MP3, and WMV Videos as Tutorials Librarians are very innovative in tutorial creation. One library in the sample used WebCT (1.8%), the e-learning system, for library tutorials. One setback is the requirement for users to use ID and password before viewing a WebCT tutorial. The WebCT tutorials in the sample do not have audio feature and are not interactive. They are text in nature and involve a lot of reading like PDF and HTML pages. MP3 (1.5% in the survey) provides audio only and users can listen, but not watch. MP3 format is not meant for visual demonstrations. WMV stands for Windows Media Video, a format developed by Microsoft Windows for Internet streaming. WMV videos need a program, a media player, to be viewed. Among many media player programs are Windows Media Player, Realplayer, PowerDVD, and more. WMV format is not very common in library tutorial creation (2.5% in the survey), but they are videos with audio and animation. They are not interactive. Below are some of the library sites to demonstrate the use of those technologies. WebCT University of British Columbia Library at http://www.library.ubc.ca/home/instruct/ Mp3 Maag Library of Youngstown State University (OH) http://www.maag.ysu.edu/help/Tutorials/Mp3_Librarytour/ WMV Videos Pace University Library at http://www.pace.edu/page.cfm?doc_id=29301 5. Conclusion One challenge for academic teaching librarians is how to find ways to incorporate library instruction into increased online courses. Another challenge is how to adapt the traditional teaching to meet the learning needs of digital savvy new undergraduates. We have identified key factors in creating successful online tutorials, but not all the academic libraries are up-to-date in the required technologies. Static tutorials are outdated. Librarians should move on from the long, tedious and stale web pages to more interesting, animated and interactive tutorials. In the best-case scenario, a library can combine all the technologies covered in this paper into one tutorial so that students can read, watch animation and have fun at the same time. The best tutorial is always a combination of good contents, logically connected links with clear verbal explanation, and animated, interactive demonstrations. HTML, CGI scripts, and tutorial software should all play a part in creating an effective tutorial. Effective tutorials should blend learning with fun. References Anderson, R. P., Wilson, S. P., Livingston, M. B., & LoCicero, A. D. 2008, "Characteristics and content of medical library tutorials: a review," Journal of the Medical Library Association, vol. 96, no.1. pp. 61-63. Armstrong, A. & Georgas, H. 2006, "Using Interactive Technology to Teach Information Literacy Concepts to Undergraduate Students", Reference Services Review, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 491-497. Association of College & Research Libraries 2000, Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, Available at: http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/ acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.cfm (accessed 7 May 2008). Brown, M., Cox, C., Gelfand, J. & Riggs, C. 2007, "Reports from the American Library Association Midwinter Meeting: Seattle, Washington, January 18-22, 2007" Library Hi Tech News, vol. 24, no.3, pp. 10-11. Course Technology 2008, IT Glossay: Programming, Available at: http://www.course.com/Careers/glossary/programming.cfm#cgi (accessed 7 May 2008). Cox, Christopher 2007, "New Frontier in Online Learning", Library Hi Tech News, vol. 24, no.3, pp. 10-11. Distance Librarian 2005, Macromedia Captivate vs. Qarbon Viewletbuilder Pro, Available at: http://distlib.blogs.com/distlib/2005/01/macromedia_capt.html (accessed 2 January 2008). Haahr, M. 2008, Random.org: True Random Number Service, Available at http://www.random.org (accessed January to April 2008). Instructional Technologies Committee 2008, Tips for developing Effective web-based library instruction, Association of College & Research Libraries, Available at: http://www.ala.org/ala/acrlbucket/is/iscommittees/webpages/instructionaltechnolo gies/tips.cfm (accessed 21 June 2008). Jones, Steve (Pew Internet & American Life Project) 2002, The Internet Goes to College: How the Students Are Living in the Future with Today's Technology, Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_College_Report.pdf (accessed 21 June 2008). Lamb, A. & Johnson, L. 2008, "The virtual Teacher-librarian: Establishing and Maintaining an Effective Web Presence", Teacher Librarian, vol.35, no. 4, pp.6771. McCann, H. & Mofford, K. 2005, Making Movies out of Screen Shot Technology, Available at: http://www.mwcc.edu/library/new/tutorials.html Pressley, Lauren 2008, ‘Using Videos to Reach Site Visitors: A TOOLKIT FOR TODAY'S STUDENT’, Computers in Libraries, vol. 28, no.6, pp.18-22. Stover, Catherine 2007. "Strong Growth in Online Enrollment, Says Sloan Report", Recruitment & Retention in Higher Education, vol. 21, no.12, pp. 3-3. Zhang, Li 2008, ‘Effectively Incorporating Instructional Media into Web-based Information Literacy’, Electronic Library, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 294-306.