Three types of “Silence” in the Writings of Three Post

advertisement

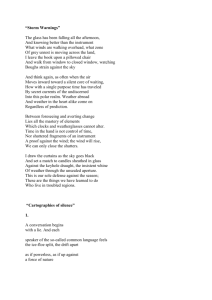

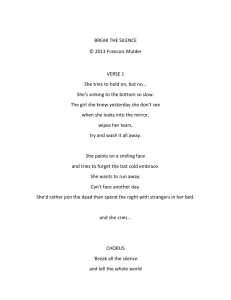

THREE METAPHORICAL USES OF “SILENCE” IN THREE FEMALE POSTCOLONIAL WRITERS’ WORKS “Silence” in postcolonial literary text connects the issues of language and national character, while in the works by female postcolonial writers, it is the prescription given to colonial females by social gender role or racial role, and also the form colonial females use to revolt against such a prescription. It is fair to say that the silence female postcolonial writers manifest in their works is actually a sound “silence”, their pens make such a sound of “silence” resound in the world of letters. Thence, “silence” is no longer “silent”, the colonial females seen in the “silence” in postcolonial texts are in fact crying revolt against the mainstream society from the periphery where they subsist. Owing to different national and cultural backgrounds, “silence” is manifested in different forms by different female writers, and different writers use “silence” to express different meanings. The “silence” manifested by the female writer of African origin MN Philips signifies the agony of being denuded of the ability to speak. The manifestation of “silence” imagery in Philips poetry is to manifest “aphasia” by using “language”, thus directs her diatribes against the racial and gender issues closely related to aphasia. The long rule over her native land, Africa, by colonists makes her people almost lose their mother tongue, therefore, the people under colonial rule fall into an “aphasic”. “silence”. In the works of Anita Desai, the fiction writer of India origin using English in her writing, the “silence” imagery is manifested more as the resistance against sexism. “Silence”, a marginal status of the sexual exiles, is often complimented as a traditional virtue of Orient females, but questioned in Desai’s writings. The “silence” in the works of Joy Kogawa, the Canadian fiction-writer and poet of Japanese origin, embraces an abundance of religions meanings. When manifesting “silence” in her fictions, she tends to use “silence” to metaphorize some highest Buddhist spiritual realm, especially the “void” or “nothing” in Buddhism. She maintains that truth 1 conceals itself in somewhere beyond all languages, no language or sound can carry truth, to express truth is bound to be “trying to discriminate but failing in finding the exact words”. A. “Silence ” of the Mutes Depicted by Marlene Nourbese Philip, a Writer of African Descent “Silence” characterizes the agony of the muteness of the colonized. Under the colonization, the colonized are deprived of their local vernaculars and are forced to use the languages of the colonized thence great anguish of the forced “muteness”, a state in which their national culture, feelings and thoughts cannot be conveyed through their national languages but through those of the foreigners’ (the colonizers’). What M.N.Philip, a writer of African breed, expresses in her writings is just the great sufferings resulted from such conditions. In Philip’s poetry the imagery of “silence” is acquired by presenting the “muteness” through “languages” thereupon pointing to race and gender, which are closely related to the “muteness”. Due to long-term colonial rule in her motherland, Africa, the native Africans nearly forget their mother tongues hence the subsequent speechless “silence”. So far She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, Philp’s third collection of poetry, is her most successful work, in which the imageries of “silence” are most densely presented. In this collection the opening paragraph of the first chapter “Every Piece of Land and Sea” immediately brings the readers to a context of diasporas soaked in sadness. The symbol of mother’s losing touch with her daughter and finding the daughter nowhere not only aptly reveals the author’s exile mood resulted from her cultural dislocation and spiritual estrangement but also serves as a necessary foreshadow for developing the theme of losing mother tongue in the subsequent parts. In Greek myth, Siras attempted to find her lost daughter, Pushfeny, but in vain. In Philip’s poems, the mother wants to hold her daughter in her own language, but like Siras, she finally fails to keep her daughter in her mother tongue, the tongue used by her ancestors. “Address on 2 the Logic of Language”, the most important piece in She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, is a statement of the theme of the entire collection. The beginning of this poem is divided in the same page into three separate columns, which are in three distinct typefaces. In the main body, namely the column in the middle, the poet writes: In the left column, the poet says: All these three columns center on the same topic but in different aspects and from different perspectives — — the difficulty of “muteness”, that is, the native language not being spoken in mother’s tongue. Owing to the loss of native language in its true sense, the colonized have to take the patriarchal languages as their native languages instead and therefore have to taste the “ bitterness of alienness” in using them. The true “mother tongue” transmits all the comforts a baby gains from its mother’s tender and assuring licks. But because of segregation by the slave owners, the mother tongue loses its capability to communicate and accordingly withers till death in the end. The loss of mother tongue, like baby’s inaccessibility to its mother’s licks, means not only danger but also sadness. Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence (1991), Philip’s last work, tells a story of an African girl who travels in boundless time and space. She is the daughter of Africa, wandering without destination in time and space beyond their historical and geographical senses. She is always seeking for her origin, the origin of culture and mother tongue. But like Siras’ failure in searching for her daughter or the daughter’s failure in finding the mother, she found nothing but “silence”. Almost all the names of the of the characters the heroine encounters in her journey are related to “silence”, and the only difference is that the letters in them are rearranged like CESLIEN, NEECLIS,SINCEEL or ECNELIS, which symbolizes the silent Africa suffering from “muteness”. II.Gender-specific “Silence” Described by Anita Desai, A Woman Writer of Indian Descent If Philip’s portrayal of “silence” is more concerned than 3 anything else with the problem of languages regarding the racial and national awareness, the imagery of “silence” presented by Anita Desai, an Indian-descent novelist writing in English, can be said to have expressed resistance against sexual discrimination. Born of a family with both western and eastern background and growing up in New Deli, Desai stamps her female characters, most of whom live a marginal life far off the man-dominant center, with the oriental silence peculiar to the traditional Indian women. Their life desires being regulated by all sorts of restrictions from religion, society and conventions, they can only silently live in solitude, an exile life neglected by most. Thus when “silence”, a marginal living condition characteristic of gender exiles, is hailed as the virtue of oriental women, Desai questions it without hesitation in her writings. Maya, the heroine in Desai’s virgin novel “Cry, the Peacock”, is a woman who seeks to be accepted by the society as a separate sex, but in the end finds it is hardly possible to accomplish this goal in the Indian institutional and cultural context. Taken as a figurine without thought and feelings, she lives in the social margin without independent personality and identity. She is exiled spiritually, her thoughts and feelings drifting along the border of the reality. She is not able to enter the reality world, for it is the domain of men; being silent and having little communication with her husband when living together, she has to retreat to her inner world. “Silence” in Indian culture is a merit considered typical of women; therefore Maya is confined to her traditional part, hard to escape. In Desai’s novels, the imagery of “silence” is always connected with that of death, which seems to be the way the heroines resist “silence” with the very silence. In “Cry, Peacock”, the reserved heroine, Maya, told her husband one day that she wanted to die, saying:”Don’t you know that I never mind if I die right now? … No one more word is necessary and all is over.” This remark sounds a thunder in silence to her husband, so does it to the readers when they try to feel Maya’s torrential emotions in disguise of silence by claiming: “no 4 one more word is necessary”. It is just by such sharp contrasts that Anita Desai succeeding in presenting “silence” that is by no means silent. In Desai’s novels, the imagery of death is always put side by side with that of “silence”. When she finds it impossible to escape all sorts conventional, religious and social restrictions, Monisha, the apparently indifferent and reserved heroine in “Voices in the City”, chose to die, a silent but the most resounding resistance to the world she dwells in. She herself after her death is silent, but as what is put in the story, “she wants to make her death the meaningful parts of her life, affirming and freeing herself, an attempt to articulate her own voices to this world.” What Desai tries to depict in her writings is just this extreme form of “silence”, viz. death, used by a group of exiles to question and resist the gender-specific diaspora. Her writings themselves are a type of audible “silence” in the sense that silence is broken by the presentation of silence. With such presentations the silent women encaged in the inner bitterness wage protests and challenges at the marginal position against the trendy culture. When the sufferings of the silent Indian women are articulated in English instead of Hindi, more listeners are attracted and the “silence” is accordingly changed into utterances. III. The Nil “Silence” Presented by Joy Nozomi Kogawa, A Feminist Writer of Japanese Descent In the works of Joy Nozomi Kogawa, a Japanese Canadian writer and poet, the imagery of “silence” takes on rich religious signification in that it is often metaphorically associated with certain supreme states in Buddhism, the states of “emptiness” and “nil” in particular. For Kogawa, truth can never be approached to through language or sounds and the attempt to express truth verbally must end up forgetting what to say when the words are on the lips. It is in Obasan, the first and the most successful novel by Kogawa, that the imagery of “silence” is cultivated to its full. The novel is autobiographical in that it gives a vivid account of what the Japanese Canadians experienced during World War II. Niomy, 5 the narrator in the novel, shares with the author a similar experience in which Niomy is sent into exile by the Canadian government to a imprisonment camp where she lives a harsh life. During WWII Niomy and her brother, Steven, were separated from their parents. Their mother was deprived by the Canadian government of the right to return to Canada after she had finished her home trip to Japan and their father was transported and sold to a farm to work as a coolie. Niomy and Steven had to live with their uncle and aunt, Samu and Obasan, the family life proceeding in deadly silence. Growing up in solitude and silence, Niomy almost lost her power to communicate with others and had been accustomed to indulging in silence. The whole piece develops on the displaying of the family history and in silence Kogawa is tracing a family history as well as the history of discrimination suffered by the whole Japanese nation. In Obasan the imagery of silence is a complex one in the sense that different meanings are acquired on different levels in different symbols. In the novel, the images of tree and forest are recurrent, for example, in the sentences like “I hide in the woods with green grass”, “I am part of the small grove”. In Buddhism, tree, bodhi tree in particular, has a special implication that practicing asceticism under a bodhi tree is helpful for learning the true meaning of Buddhism. What Obasan attempts to achieve is the imagery of “silence” with rich Buddhism implications, by which the author poses questions to the values of the real world and language, concluding that truth is always on the move and words are incapable of describing the ever-changing world. As a result, truth exists only in silence, a state of nil devoid of words or objects. At this juncture, such “silence” is presented as a kind of spiritual target. Furthermore, stone, another recurrent image in the novel, is taken to signal silence, the forced and wordless silence. Just as the writer’s words in the novel “I hate soundlessness and I hate stone”, such forced silence results from the racial discrimination and the sexual stipulations on the parts of traditional Japanese women. Sea, a third recurrent image concerning silence in the novel, 6 symbolizes “audible” silence, a special discourse to present and to break silence. In narration the characters in the novel strike the reader eternally mute and silent and their hearts are tightly enclosed. In the parts where there are poems or songs, blanks are left and they are in fact another way of presenting silence in that the silence they stands for itself is a discursive strategy. With these blanks the writer means to tell us the fact that the blank spaces surrounding the words are more important than words themselves and their implications are far rich than what the words contains. Readers familiar with oriental cultures are prone to associating the imagery of silence presented in Obasan with some conceptions, for instance, “sudden enlightenment” or “Faramita”, in Buddhism. Truth is a Faramita domain that cannot be approached to through language, nor can it be apprehended through words or idea interpretations. Only in instant sudden enlightenment and in speechless nil can truth be reached. Judging from the manifestation of “silence” by the above three female writers, silence and utterance is put forward as a question or laid out as an option to guide their readers to rethink language from the angles of racial discrimination and sexism. Different national and cultural background make the “silence” manifested in different messages, however, to put it briefly, the silence manifested in their works includes merely the following states: one is the compelled silence, one is the silence containing truth which is sought after in the heart, one is keeping the lips sealed and one silence is itself a language, a sound silence. The pursuit of silence is in reality an opposition to silence, when “silence” is employed as a resistant language, that compelled “silence” is broken. Ren Yiming Literature Institute Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences 7