Dependent variable - Document Server

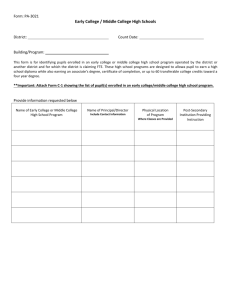

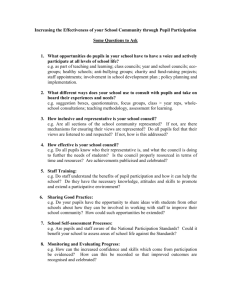

advertisement

DETERMINANTS OF ABSENTEEISM AMONG PRIMARY SCHOOL PUPILS IN UGANDA BY MAYANJA EDISON BSc.Educ (Hons), MUST 2008/HD15/12980U A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF STATISTICS OF MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAY 2011 DECLARATION I, Mayanja Edison , hereby declare that the work presented in this dissertation is my original work and has never been submitted to any academic institution for an academic award. Signed:………………………………. Date:…………………………….. Mayanja Edison i APPROVAL This dissertation has been submitted for examination with the approval of the following supervisors: 1. Signed…………………………………. Date………………………….. Dr. L.K. Atuhaire School of Statistics and Applied Economics Makerere University, Kampala 2. Signed…………………………………. Date……………………………. Dr. William Kaberuka School of Statistics and Applied Economics Makerere University, Kampala ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my dearest mum Mrs.Zamu Bukenya. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my supervisors; Dr.William Kaberuka and Dr. L.K. Atuhaire of the School of Statistics and Applied Economics Makerere University, Kampala whose supervision, motivation, guidance and advice at each stage of the course made it possible for the research work to score its value. I am sincerely grateful for all the time and energy they have invested in me and may the Almighty God reward them abundantly. I owe my gratitude to the staff of the School of Statistics and Applied Economics Makerere University, Kampala for their cooperation that made the study worthwhile. I would like to extend my appreciation to all my classmates but special appreciation go to Ssekasanvu Joseph, Tumugumye Philip, Ssettuba absalom, Nalukenge Betty, Kunihira Andrew, Kuteesa Andrew and Sibenda Sadoke for their support in varied forms. I also express my indebtedness to my Mum, Bulime Paul, Sseremba Freddie, Kivumbi Eddie and Dr.Nsubuga Angel for the financial support and encouragement they offered to me. Completion of this work was a result of both the explicit and implicit support of my sisters and brothers; Daulah, Mayimunah, Fatuma, Hadjah, Shamim, Susan, Edith, Racheal, Eddie and Hassan to whom I am grateful. The support provided by my fiancée Fortunate Tumwebaze was enormous that I have no words to use but to say thank you. It is impossible to remember all and I apologize to those I have inadvertently left out. May God bless you all. iv ABSTRACT The broad objective of this study was to identify the factors that explain absenteeism among primary school pupils in Uganda. This study employed secondary cross-sectional data on absenteeism among primary school pupils from 2006 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey which was a descriptive statistical survey. The analysis was done at three levels, that is, at Univariate analysis descriptive statistics was used; at Bivariate analysis cross-tabulations were done to establish the relationship between absenteeism among primary school pupils and the indepedent categorical variables ,the results were discussed using Pearson’s Chi-Square test and at Multivariate analysis, a complementary log-log model was fitted to establish the most significant factors determining absenteeism among primary school pupils in Uganda. The study revealed that household size, type of place of residence and disability stati of the pupil were the significant determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils in Uganda. It was found out that absenteeism among pupils with one type of disability was 1.204 times that of those without any disability. It was also established that absenteeism among pupils with two types of disabilities was 1.925 times that of those without any disability. Absenteeism among pupils residing in rural areas was found to be 1.522 times that of those residing in urban areas. Absenteeism among pupils from households with more than 7 members was found to be 0.879 times that of those from households with 7 members and below. The study recommends sensitization of rural parents/guardians on their roles and responsibilities so as to fulfill their primary parental responsibility of monitoring their v children’s school attendance, providing them with school requirements and doing everything possible to ensure that their children are regular at school. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ................................................................................................................. i APPROVAL ....................................................................................................................... ii DEDICATION ................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ v TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. vii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. ix ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................... x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background to the study ........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Statement of the problem .......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Objectives of the study.............................................................................................. 4 1.4 Hypotheses of the study ............................................................................................ 4 1.5 Significance of the study........................................................................................... 5 1.6 Scope of the study ..................................................................................................... 6 1.7 The conceptual frame work of determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils. .............................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ................................................................... 10 2.2 Socio-Demographic factors .................................................................................... 10 2.3 Socio-economic factors ........................................................................................... 16 CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ......................................................................... 19 3.2 Data source.............................................................................................................. 19 3.3 Data analysis ........................................................................................................... 22 CHAPTER FOUR: DETERMINANTS OF ABSENTEEISM AMONG PRIMARY SCHOOL PUPILS ............................................................................................................ 26 4.3 Univariate analysis and Bivariate analysis ............................................................. 26 4.4 Multivariate analysis ............................................................................................... 31 vii CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY OF THE FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................................. 35 5.1 Summary of the findings ......................................................................................... 35 5.2 Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 36 5.3 Recommendations ................................................................................................... 36 References ......................................................................................................................... 39 viii LIST OF TABLES Table 4.1: Percentage distribution of absenteeism among primary school pupils………25 Table 4.2: Percentage distribution of Socio-Demographic factors and Cross tabulations of Absenteeism by Socio-Demographic factors…………………27 Table 4.3: Percentage distribution of Socio-Economic factors and Cross tabulations of absenteeism by Socio-Economic factors……………………..29 Table 4.4: Results of the Complementary log-log regression model of absenteeism among Primary school pupils according to the independent variables………………31 ix ACRONYMS FAWE: Forum for African Women Educationalists MDGs: Millennium Development Goals MoES: Ministry Of Education and Sports NGOs: Non-Governmental Organizations PLE: Primary Leaving Examination UBOS: Uganda Bureau of Statistics UDHS: Uganda Demographic Health Surveys UNEB: Uganda National Examination Board UNHS: Uganda National Household Survey UPE: Universal Primary Education UWESO: Uganda Women’s Effort to Save Orphans x CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the study Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 2 and 3 aim at achieving universal primary education and to promote gender equality and empower women respectively, educating a nation remains the most vital strategy for the development of the society throughout the developing world (Aikaman & Unterhalter, 2005). Many studies on human capital development agree that it is the human resources of a nation and not its capital or natural resources that ultimately determine the pace of its economic and social development. The principal institutional mechanism for developing human capital is the formal education system of primary, secondary, and tertiary training (Nsubuga, 2003). Since education is an investment, there is a significant positive correlation between education and economic-social productivity. Educated people are likely to have improved standards of living, since they are empowered to access productive ventures, which will ultimately lead to an improvement in their livelihoods. The role of education therefore, is not only to impart knowledge and skills that enable the beneficiaries to function as economies and social change agents in society, but also to impart values, ideas, attitudes and aspirations important for natural development. The straightforward linkage between education is through the improvement of labor skills, which in turn increases opportunities for well paid productive employment. This then might enable the citizens of any nation to fully exploit the potential positively. 1 The structure of primary education in Uganda is such that at the age of about 6 years a child enters school for 7 years, at the end of 7 years he/she is expected to take Primary Leaving Examinations (PLE) conducted by the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB). To fully improve the literacy in Uganda, the government introduced Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 so as to achieve the educational related MDG 2 (that by 2015, all children, boys and girls should be able to complete a course of primary schooling) this has greatly increased the primary school pupil enrollment from around 3 million pupils in 1997 to about 7.5 million in 2003 and over 7.6 million in 2005/06 (UNHS, 2005/2006). At present both under age and over age pupils are enrolled as education is free. Though education is free, research findings have revealed that pupil absenteeism is increasing. According to Nakanyike, Kasente and Balihuta (2003), on average, a child misses 23 days in a year. This rate is much higher than the 13 days a year that was reported by Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and Macro International Inc. (2001). In a week the average number of days missed is 2 days as revealed by UBOS and Macro International Inc. (2007) Hunger, poor nutrition and UPE related fees have been mentioned to be the key causes of absenteeism among UPE school pupils (UWESO, 2008). Although UPE is supposed to be free, it is known that there are other costs related to school attendance like uniforms, stationery, transport, boarding fees, etc, which may be prohibitive to the households. 2 Indifference to education (which includes parents’ not favoring education and pupils not willing to attend further) and schools being too far are also a major reason why children are likely to be absent from school (UNHS, 2005/2006). Factors noted why absenteeism occurs in Uganda primary schools are illness, domestic work, pupils don’t want to go to school, working for a family farm/business or other employer, attending a funeral or other ceremony, problems with school uniform, and having no stationery (UBOS and Macro International Inc,2007). 1.2 Statement of the problem Despite the Uganda government’s effort of introducing UPE in 1997 that is completely free and abolition of all kinds of fees in UPE schools, absenteeism among primary school pupils is on an increase. Kagolo (2009) cites Atima (2009) from directorate of education standards of Ministry Of Education and Sports (MoES) who reported that only 55 percent of the pupils attend school at the beginning of the term and during examinations and this is worse in Government aided schools that are free compared to private ones that are not free. A pupil that is frequently absent fails to master a minimum of skills and competences and is likely to be forced to repeat the grade, this not only doubles the cost to educate that pupil but also reduces the pupil’s morale to continue schooling hence eventual dropping out of school this lets down government’s policy of attainment of MDGs 2 and 3 that aim at educating all children to the end of primary level and promoting gender equality by 2015 respectively. Absenteeism has been noted as one of the major cause of school 3 dropouts in Uganda (Nakanyike et al., 2003). Therefore there was need to identify major determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils so as more absenteeism control measures could be developed and existing ones could be strengthened to slow down the increasing rate of pupil absenteeism in Uganda. 1.3 Objectives of the study 1.3.1 General objective The general objective of this study was to identify the factors that explain absenteeism among primary school pupils in Uganda. 1.3.2 Specific objectives The specific objectives of this study were the following; i) To determine whether socio-demographic factors influence absenteeism among primary school pupils. ii) To determine whether socio-economic factors influence absenteeism among primary school pupils. 1.4 Hypotheses of the study In order to achieve the above objectives the following hypotheses were considered; i) Sex of the primary school pupil has no effect on his/her absenteeism. ii) Age of household head has no influence on the primary school pupil’s absenteeism. iii) Sex of household head has no effect on primary school pupil’s absenteeism. 4 iv) Relationship of pupil to the household head does not affect primary school pupil’s absenteeism. v) Survivorship status of the parent of the primary school pupil has no influence on the pupil’s absenteeism. vi) Absenteeism of the primary school pupil is independent of the pupil’s disability status. vii) Residence of the pupil has no effect on primary school pupil’s absenteeism. viii) Household size has no influence on primary school pupil’s absenteeism. ix) Highest education level attained by household head has no effect on primary school pupil’s absenteeism. x) Absenteeism of the primary school pupil is independent of the household socio-economic status. 1.5 Significance of the study Pupils who are absent frequently or for long periods are likely to have difficulty in mastering the material presented in class, making absenteeism a critical education issue. Absenteeism is one of the reasons for pupil’s poor grades. Since the researcher intended to identify and estimate the determinants of pupil absenteeism in primary schools this will help to provide information to the relevant authorities to enable them come up with/ strengthen existing policies regarding appropriate reduction on pupil absenteeism. In addition the findings of this study will also be of great importance to academicians, it will serve as a study guide and it is intended to add to the knowledge of the researchers in this field of study. 5 1.6 Scope of the study The study focused on determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils in the whole of Uganda. In this study all data with missing values and don’t know were not considered. 6 1.7 The conceptual frame work of determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils. Figure 1.1 Socio-demographic factors Sex of the pupil Age of household head Sex of the household head Relationship of the pupil to the household head Survivorship status of the parents of the pupil. Disability status of the pupil (any difficulty in; seeing, hearing, walking or climbing stairs, remembering, self-care and communicating. Pupil absenteeism Socio-economic factors Type of place of residence Size of the household Highest education level attained by household head Household Socio-economic status Independent variables dependent variable The conceptual frame work in figure 1.1 is based primarily on one developed by Manuel Crespo (1984). The model explains the effect of socio-economic and socio-demographic factors on absenteeism among primary school pupils. Relationship of the pupil to the household head, survivorship status of the parent of the pupil determines whether/or not the pupil will be provided adequately with basic school requirements like stationery, uniform and fees, hence affecting pupil’s absenteeism. Sex of the pupil determines the 7 opportunity cost to education and who will do what type of domestic work and hence determine absenteeism. Disability status of the child determines the ease a child finds in going to school and hence determine absenteeism. Sex and age of the household head determines the magnitude of control over the children this influences pupil’s willingness to go to school. Household Socio-economic status determines the ability to provide a child with basic school requirements and ability to control illness for example buying mosquito nets, having protected water sources like taps and better toilet facilities hence affecting pupil absenteeism. Size of the household can increase or reduce on the domestic work available, financial burden hence determine the level of absenteeism. Education level of the household head determines the value he/she holds to education and the inspiration for education pupils in the household derive from him since a household head is a role model to the members of the household. This influences attainment of school requirements, children’s willingness to attend school and hence absenteeism. Residence influences accessibility of schools, pressure on children to engage in petty business to support the household (e.g. in domestic and agricultural duties) hence influencing absenteeism. 1.8 Structure of dissertation This study is organized into five chapters. Chapter one deals with introduction of the study, that is, background to the study, statement of the problem, objectives of the study, hypotheses of the study, significance of the study, scope of the study and the conceptual frame work of determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils. Literature review is presented in chapter two. Chapter three is on methodology that was used in the 8 study, which includes: source of data, description of variables and methodology of data analysis. Determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils are discussed in chapter four. Chapter five gives the summary of findings, conclusions and recommendations. 9 CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 Introduction This chapter reviews the literature on primary school pupil absenteeism. There has been quite a considerable amount of literature on primary school pupil absenteeism both in Uganda and on the international scene. The chapter attempts to shade some light on what has been said on primary school pupil absenteeism. 2.2 Socio-Demographic factors Sex of the pupil Boys absent themselves from school more than girls despite the fact that in Ugandan primary schools there are more boys than girls this was revealed by the rapid head count in primary schools (MoES, 2009). According to UBOS and Macro International Inc. (2007) report, it showed that male pupils missed school more than female pupils. However this is in contradiction with the findings of the research done by Runhare and Gordon (2004) in Zimbabwe that found out that there was higher absenteeism among girls than boys because of economic hardships, negative cultural and socializations factors, HIV/AIDS related factors and over burdening household chores. Studies have indicated the preference many households have for the education of boys over girls, with girls’ education often deemed less important ( Admassie, 2003; Boyle, Brock, Mace & Sibbons, 2002; Nekatibeb, 2002; Rose & Al Samarrai, 2001). Boyle et al. (2002) suggest that households in their study tended to see boys’ education bringing 10 greater future economic rewards, which was not to be the case with girls. Indeed, educating a girl is often seen as a poor investment because the girl will marry and leave home, bringing the benefits of education to the husband’s family rather than to her own. Similarly, in Guinea parents mentioned that primary schooling was irrelevant to girls’ future roles. In such cases girls will not be facilitated with schooling necessities like boys and will end up being more absent than boys. Research highlights a number of important points with regard to education and rites of passage ceremonies which mark the move from childhood to adulthood. The ceremony and preparations for it may overlap with the school calendar, which can increase absenteeism (Boyle et al., 2002; Kane, 2004; Nekatibeb, 2002). Boys in Guinea undertaking initiation ceremonies had primary schooling disrupted, with ceremonies sometimes taking place in term time, absenteeism lasting up to one month, while for girls it was often considered ‘shameful’ for them to return to school (Colclough et al., 2000). This move into adulthood at times means that ‘new’ adults can think themselves too grown up for schooling. Nekatibeb (2002) describes how communities in Ethiopia accept these girls as ‘adults’, but teachers or schools continue to consider them as children and this may create tension. Girls as they grow, they experience puberty changes that are more likely to increase absenteeism than boys for example getting attracted to men and using school time to meet them since it is the only chance they have as they are still staying with their parents/guardians. It is during primary schooling when girls start their menstruations. 11 UNICEF (2005) estimates that 1 in 10 school-age menstruating African girls skip school four to five days per month or drop out completely because of lack of sanitation facilities. In Uganda, many disadvantaged menstruating primary school girls who lack sanitary towels decide to stay at home for the days the menstrual cycle lasts due to fear of inconveniences. This means that these girls are absent from school for about four days per month (FAWE Uganda, 2004). This absenteeism leads to poor academic performance and subsequent dropping out of school. Age of house hold head Household head’s age contributes to absenteeism in away that absenteeism is high in households where the head is child or very old unlike in those ones headed by mid-adults. This is because household heads that are children or grandparents don’t usually exert enough control over the children. A study done in Malawi by Chimombo et al. (2000) revealed that in some areas a lot of night activities such as dances and initiation ceremonies contributed to absenteeism from school. It was noted that some girls and boys as young as 15 years would spend the whole night out with little interference from the grandparents or these children were sleeping separately in their own huts. Such children would get so tied that would not attend classes the following day. Sex of the household head Al Samarrai and Peasgood’s (1998) research in Tanzania suggests that the father’s education has a greater influence on boys’ primary schooling and the mother’s on girls’. Glick and Sahn’s (2000) results offer some similar outcomes to Al Samarrai and 12 Peasgood (1998): improvements in fathers’ education raise the schooling of both sons and daughters, but mothers’ education has significant impact only on daughters’ schooling. Therefore if the household head is a male, then, boys and girls are likely to have similar school attendance patterns whereas in those headed by females, boys are likely to be more absent than girls. Men tend to exert enough control on children as far as school attendance is corned more than women. Therefore if the household head is a male, pupil absenteeism is likely to be low compared to female headed households. Relationship to the household head If a child is a daughter or son to the household head is likely to get all schooling requirements and his/her school attendance will be high unlike for his/her counterparts. Research done by Konate, Gueye and Nseka (2003) reveals that relationship to the household head has an impact on pupil’s school absenteeism in away that children of the head of household are usually favored over others in the household (i.e. those fostered, entrusted to the family and those living in it with parents other than the heads of household). Survivorship status of the parents of the pupil Presence of a pupil’s parents alive has an impact on his/her absenteeism, particularly in poorer communities. Grant and Hallman’s (2006) research on education access in South Africa shows children living with mothers were significantly less likely to have absented 13 from school relative to those whose mothers were living elsewhere or whose mothers were dead. Orphan hood often exacerbates financial constraints for poorer households and increases the demands for child labor and absenteeism (Bennell, Hyde & Swainson, 2002; Ainsworth, Beegle & Koda, 2005). In Uganda though there is UPE, orphans are working even on school days so as to get money to buy scholastic materials hence absenting from school. Recent studies done in Burundi show that attendance rates vary by category of orphan (Guarcello, Lyon & Rosati, 2004). Paternal orphans attended schools in greater proportions than maternal orphans; male orphans were more likely to attend school than female orphans. Double orphans less likely to attend school full-time in combination with work than non orphans. Being a single orphan reduced the probability of attending school full-time by 11 percentage points, and of attending school in combination with work by four percentage points. However, research done in Tanzania by Ainsworth et al. (2005) attempted to measure the impact of adult deaths and orphan status on primary school attendance and hours spent at school. There was no statistically significant difference in attendance rates by orphan status. Often children dealing with bereavement have to move into foster care. Not only are they dealing with the trauma of this bereavement, but they often have to move households and schools. This disrupts schooling patterns and can be linked to periods of absenteeism. 14 In many societies, in Africa in particular, a large number of children are fostered estimated to be 25% of children (Zimmerman, 2003). There can be both positive and negative effects of fostering on educational access. In many cases children are fostered in order to allow them greater educational opportunities. However based on an analysis of black South African children, Zimmerman (2003) claimed foster children were no less likely than non-orphans to attend school. School attendance is highest for fostered children in Burundi (Guarcello et al., 2004), compared to children living with their immediate family. This suggests that children are often being fostered in order to get better educational opportunities. Disability status of the child Because of their status, persons with disabilities are vulnerable and suffer from social exclusion, stigma, and discrimination (UBOS and Macro International Inc, 2007); this leads to reduction of their morale of attending school. Pupils with difficulties in seeing, hearing, walking or climbing stairs, in remembering or concentrating, in self-care, and in communicating need a conducive environment for participation effectively and friendly service delivery. For example if the child has a difficulty in walking and he has to walk for a long distance to get to school, this child is likely to be more absent. Chimombo et al. (2000) cites Peter’s (2003) claims that ‘the vast majority of children with disabilities have mild impairments. These children most likely constitute a significant percentage of grade-level repeaters’, this reduces the pupil’s morale for schooling and hence an increase in absenteeism. 15 2.3 Socio-economic factors Type of place of Residence of the pupil The rate of absenteeism is higher in rural areas than in urban areas as reported by UBOS and Macro International Inc (2007). Households in rural areas tend to be poorer, schools more inaccessible, household members less educated and pressures on children to work to support the household (e.g. in domestic and agricultural duties), greater. While in urban locations, there tend to be more schools and the choice of options available to households are greater. However, findings of Eoghan (2008) reveal that in Ireland rates of non-attendance in primary schools are higher in towns and cities than they are in rural areas. Research points to distance to school being an important factor in educational access, particularly for rural populations (Boyle et al., 2002; Mfum-Mensah, 2002; Nekatibeb, 2002; Porteus et al., 2000). In research carried out in Ethiopia and Guinea, ‘as elsewhere, the greater is the distance from home to school, the more likely it is that a child will be absent (Colclough, Rose & Tembon, 2000); for younger children, particularly if the journey is deemed too far (Juneja, 2001); for girls where parents/guardians are afraid of sexual harassment, especially as they grow older (Colclough et al., 2000; Nekatibeb, 2002; the PROBE Team,1999); and for girls who are seen as being ‘weaker’ than boys (Colclough et al., 2000). Therefore in rural areas where schools are far from pupil’s homes, pupils are more likely to be absent than urban pupils were schools are near to pupils’ homes and means of transport to school like taxis are in plenty. 16 Household size How many members are within the household is important in many cases and can be a ‘significant determinant’ of absenteeism. But research differs on the impact of household size on absenteeism. Some studies indicate that with larger household sizes (and in particular numbers of children) the financial burden/potential workload is greater; children are less likely to attend school. However, with more children in the household, jobs can be spread between them and siblings more likely to attend, e.g. in Ethiopia (Colclough et al., 2000). Research in Pakistan indicates that while an increase in family size reduces a girl child’s household work, the presence of younger children appears to increase their workload (Hakzira & Bedi, 2003). As in other studies, the number of siblings under 5 years of age has a strongly negative impact on older girls’ schooling and leads to absenteeism. Highest education level attained by the household head Literate household heads are not only more likely than illiterate ones to enroll their daughters and sons in school, but also to ensure that the school attendance of their children is regular. Literate household heads feel it is profitable to educate their children and look at sending their children to school as a wise investment for the future unlike illiterate ones. Literate household heads will do whatever is required for the child not to miss school like providing scholastic materials, paying fees in time. To illiterate parents education is perceived to be of limited worth when after completion of schooling (Primary), there is no substantial difference between someone who has been to school and one who hasn’t. Some researchers indicate that non-educated parents cannot provide 17 the support or often do not appreciate the benefits of schooling (Juneja, 2001; Pryor & Ampiah, 2003), children of such parents/household heads will be more absent than those of educated ones. The household head is a role model to the rest of the household members (Hunter & May, 2003); heads that are educated are likely to inspire schooling children to attain high qualifications like theirs’ and one way to achieve this is regular attendance of school. Therefore pupils from households headed by uneducated heads lack education role models and are more likely to be absent from school than those from households of educated heads. Household socio-economic status Ownership of a radio and television leads access to efficient communication this can help pupil’s to see and listen to highly qualified people like doctors and be inspired to study to be like them, refrigerator ownership as an indication of the capacity for hygienic storage of foods to control illness, ownership of a means of transportation as a sign of the household’s level of access to public places like schools, ownership of a farm of animals that increases the demand for the child labor and type of water source that can contribute to water contamination that leads to illness hence absenteeism. Therefore there is a positive correlation between household’s wealth index the pupil’s rates of absenteeism. 18 CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction This chapter discusses the methodology that was employed to obtain the results of this study. It reflects the source of data, description of variables and data analysis. 3.2 Data source This study employed secondary cross-sectional data on absenteeism among primary school pupils from 2006 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey which was a descriptive statistical survey. 2006 UDHS was designed to allow separate estimates at the national level and for urban and rural areas of the country. Portions of the northern region were over sampled in order to provide estimates for two special areas of interest: Karamoja and internally displaced persons (IDP) camps. A sample of 9,864 households was selected for the 2006 UDHS survey. This sample was selected in two stages. In the first stage, 321 clusters were selected from among a list of clusters sampled in the 2005-2006 Uganda National Household Survey that was carried out by UBOS. This matching of samples was conducted in order to allow for linking of 2006 UDHS health indicators to poverty data from the 2005-2006 UNHS. The clusters from the Uganda National Household Survey were in turn selected from the 2002 Census sample frame. For the UDHS 2006, an additional 17 clusters were selected from the 2002 Census frame in Karamoja in order to increase the sample size to allow for reporting of Karamoja-specific estimates in the 19 UDHS. Finally, 30 IDP camps were selected from a list of camps compiled by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs (UN OCHA) as of July 2005, completing a total of 368 clusters. In the second stage, households in each cluster were selected based on a complete listing of households. In the 321 clusters that were included in the UNHS sample, the lists of households used were those generated during the UNHS listing operations April-August 2005. The UNHS sampled ten households per cluster. All ten were purposively included in the UDHS sample. An additional 15 to 20 households were randomly selected in each cluster. The 17 additional clusters in Karamoja were listed, and 27 households were selected in each cluster. The selected IDP camps were divided into segments because of their large size, and one segment selected in each camp. Then a listing operation was carried out in the selected segment, and 30 households were selected in each camp from the segment of the map that was listed. All women age 15-49 who were either permanent residents of the households in the 2006 UDHS sample or visitors present in the household on the night before the survey were eligible to be interviewed. In addition, in a subsample of one-third of all the households selected for the survey, all men age 15-54 were eligible to be interviewed if they were either permanent residents or visitors present in the household on the night before the survey. 3.2.1 Description of variables i) Dependent variable The dependent variable was absenteeism among primary school pupils. Absenteeism from school refers to absence (non-attendance) from school. School absenteeism is of two types, namely: authorized absence and unauthorized absence. Authorized absence is 20 an absence with permission from the teacher or other authorized representative of the school. This includes instances of absence for which a satisfactory explanation has been provided (e.g. illness, family bereavement, religious observance) while an unauthorized absence is absence without permission from a teacher or other authorized representative of the school. This includes all unexplained or unjustified absences. However students under taking approved and supervised educational activities conducted away from the school (e.g. educational visits) are deemed to be present at the school. In this study both authorized absence and unauthorized absence were treated as absence from school. ii) Independent variables Education level of the household head This was a categorical variable with categories, namely: no education, primary, secondary and more than secondary. Survivorship status of the parents of the pupil This was a categorical variable with categories, namely: double orphan, single orphan and not orphan. Sex of the pupil This was a categorical variable with two categories, that is, males and females. Sex of the household head This was a categorical variable with two categories, that is, males and females. Household size This was categorized into two groups, namely: 7members and below and more than 7 members. 21 Age of the house hold head This was categorized into three groups, that is, less than 30, 30-49 and more than 49. Residence This was a categorical variable with two categories, that is, urban and rural. Relationship of the pupil to the household head This was a categorical variable with categories, namely: head, other relative, son/daughter, grand child, brother/sister, niece/nephew, adopted/foster/step child. Household socio-economic status This was a categorical variable with categories, namely: poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest. Disability status of the pupil This was a categorical variable with categories, namely: no disability, one type of disability, two types of disabilities and more than two types of disabilities. 3.3 Data analysis The data was analyzed using STATA Version 9.0 software. Analysis was done at three levels; univariate, bivariate and multivariate analysis. 3.3.1 Univariate analysis Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the characteristics of the household. Frequency tables were used to summarize all the independent variables. 22 3.3.2 Bivariate analysis Bivariate analysis was conducted to establish the associations between pupil absenteeism and independent categorical variables. Cross- tabulations were done and the association between absenteeism among primary school pupils and the categorical independent variables were discussed. This was done using the Pearson’s Chi-Square test. The chisquare statistic ( 2 ) that was used is of the form; r c 2 (Oij Eij )2 i 1 j 1 Eij ……………………………………………………………(3.1) Where; r = number of categories of the independent variable c = number of categories of pupil absenteeism Oij = observed frequency in row i and column j Eij = expected frequency in the row i and column j With the 2 test, the analysis was based on the p-value of 0.05 as the level of significance. The probability of rejecting/accepting the hypothesis being tested. If the pvalue was greater than or equal to 0.05, then the statistical relationship between pupil absenteeism and independent variable under study was not significant. On the other hand if the p-value was found to be less than 0.05, then, there was a significant statistical relationship between the two variables such that if one of them changed, the other would also change. 23 3.3.3 Multivariate analysis The multivariate analysis was used to establish the relationship between absenteeism among primary school pupils (dependent variable) and several independent variables. Since absenteeism among primary school pupils was a binary outcome (attended all school days during the week preceding the survey or absent from school for one or more days during the school week preceding the interview), a complementary log-log model was used. Yi = 1, pupil was absent from school for one or more days during the school week preceding the interview. 0, pupil attended for all school days during the school week preceding the interview. The Complementary log-Log model was used to establish the most significant factors determining absenteeism among primary school pupils. The form of the complementary log-log model is as below; log log 1 p x x i 1 1i 2 2i ... k x ki …………………………….(3.2) Where; p i is the probability that the pupil i was absent from school for one or more days during the school week preceding the interview. is a constant j for j 1,2,..., k are parameter estimates that explain the change in the absenteeism among primary school pupils as a result of change in the independent variable. x ji ; i 1, 2,..., k are the independent variables 24 While fitting the model, the independent variables that were used at this level of analysis were only those variables which had shown a strong association with absenteeism among primary school pupils whose p-value would have been less than 0.05. The researcher computed relative risks by first deriving the expression for p i from equation (3.2). The expression takes the form below; p 1 e e 1 X 1i .. k X ki i Then from the definition of relative risk RR, RR P1 / x P1 / 0 The expression for RR was derived and is of the form below; RR 1 e e j 1 e e ……………………………………(3.3) The results of the complementary log-log model were discussed by looking at the relative risks and the p-values corresponding to different coefficients. The p-values which were less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant and the relative risks which were less than one were taken to be reduced risks and those greater than one were taken to be increased risks. 25 CHAPTER FOUR DETERMINANTS OF ABSENTEEISM AMONG PRIMARY SCHOOL PUPILS 4.1 Introduction This chapter presents and discusses the findings of the study. The analysis was done at three levels, namely: univariate, bivariate and multivariate analysis. 4.2 Absenteeism among primary school pupils The researcher summarized absenteeism among primary school pupils as indicated in Table 4.1. Table 4.1: Percentage distribution of absenteeism among primary school pupils Absent Frequency Percentage No 6,634 80.2 Yes 1,636 19.8 Total 8,270 100.0 19.8 percent of the pupils missed school compared to 80.2 percent who attended all the school days. 4.3 Univariate analysis and Bivariate analysis In this study, at the univariate analysis the researcher summarized all the indepedent variables using frequency tables. Bivariate analysis was done to determine and explain the relationship between; socioeconomic factors and absenteeism among primary school pupils and socio-demographic factors and absenteeism among primary school pupils. At this level, cross tabulations of 26 the independent categorical variables and absenteeism among primary school pupils was done and the Chi- square statistic was used to discuss the results. 4.3.1 Socio-demographic factors Table 4.2 showed that; sex of the pupil (51.4 percent were boys and 48.6 percent were girls), relationship of the pupil to the household head (0.1 percent were household heads, 69.5 percent were sons/daughters, 15.1 percent were grand children, 2.4 percent were brothers/sisters, 7.2 percent were nieces/nephews, 3.1 percent were other relatives and 2.6 percent were adopted/foster/step children of household heads), survivorship status of the parents of the pupil (6.8 percent of the pupils were double orphans, 15.6 percent were single orphans and 77.6 percent were not orphans) and age of household head ( 8.2 percent had less than 30 years, 61.4 percent were aged from 30 to 49 years and 30.4 percent were above 49 years) were considered in the study, however, it was found out that they had no statistical significant relationship with absenteeism among primary school pupils. 27 Table 4.2: Percentage distribution of Socio-Demographic factors and Cross tabulations of Absenteeism by Socio-Demographic factors Percentage distribution Variable Frequency (%) Overall 8270 100.0 Cross tabulations of Absenteeism by Socio-Demographic factors 2 Number % (p-value) absent Absent 1,636 19.8 7,372 720 124 54 89.1 8.7 1.5 0.7 1,413 166 45 12 19.2 23.1 36.3 22.2 4,252 4,018 51.4 48.6 860 776 20.2 19.3 1.0844 (0.298) 5,751 2,519 69.5 30.5 1,101 535 19.1 21.2 4.8407 (0.028) 10 5,748 1,244 194 599 260 215 0.1 69.5 15.1 2.4 7.2 3.1 2.6 1 1,141 234 26 131 58 45 10.0 19.9 18.8 13.4 21.9 22.3 20.9 9.2053 (0.162) 565 1,285 6,420 6.8 15.6 77.6 107 265 1,264 18.9 20.6 19.7 0.8611 (0.650) 681 5,074 2,515 8.2 61.4 30.4 154 983 499 22.6 19.4 19.8 3.9810 (0.137) Disability status of the pupil No disability One type of disability Two types of disabilities More than two types of disabilities Sex of pupil male female Sex of household head male female Relationship of pupil to the household head head Son/daughter grandchild Brother/sister Niece/nephew Other relative Adopted/foster/stepchild Survivorship status of the parents of the pupil Double orphan Single orphan Not orphan Age of household head Less than 30 30-49 above 49 28.1162 (0.000) 28 Disability status of the pupil In this study disability status of the pupil was considered to find out its relationship with absenteeism among primary school pupils. Table 4.2 showed that 89.1 percent of the pupils didn’t have any disability, 8.7 percent had only one type of disability, 1.5 percent had two types of disabilities and 0.7 percent had more than two types of disabilities. In determining the association between disability status of the pupil and pupil absenteeism, it was found out that; of the pupils with no disability 19.2 percent were absent, 23.1 percent, 36.3 percent and 22.2 percent of the pupils with only one type of disability, two types of disabilities and more than two types of disabilities respectively were absent as indicated in Table 4.2. The association between disability status of the pupil and pupil absenteeism was significant (p= 0.000) Sex of household head In this study efforts were made to determine the association between sex of household head and absenteeism among primary school pupils. It is believed that sex of household head is associated with pupil absenteeism. Results in Table 4.2 showed that 69.5 percent of the household heads were males and 30.5 were females. Findings of this study in Table 4.2 showed that of those pupils from male headed households 19.1 percent were absent and 21.2 percent from female headed households were absent. Pupils from female headed households were more absent than those from male headed, this could be because males tend to exert enough control on children as far as school attendance is concerned more than females. There was a significant relationship between sex of household head and pupil absenteeism (p=0.028). 29 4.3.2 Socio-economic factors Household size Table 4.3 showed that 57 percent of the households had 7 members and below whereas 43 percent had more than 7 members. Further more, 21 percent of the pupils from households with 7 members and below were absent and those absent from households with more than 7 members were 18.2 percent. There was a statistical significant relationship between household size and pupil absenteeism (p= 0.001). Table 4.3: Percentage distribution of Socio-Economic factors and Cross tabulations of absenteeism by socio-economic factors Percentage distribution Variable Frequency (%) Overall 8270 100.0 Cross tabulations of absenteeism by socio-economic factors 2 Number % absent (p-value) absent 1,636 19.8 1,646 5,168 1,050 406 19.9 62.5 12.7 4.9 347 1,028 189 72 21.1 19.9 18.0 17.7 4.9648 (0.174) 515 7,755 6.2 93.8 65 1,571 12.6 20.3 17.7472 (0.000) 1950 1,644 1,699 1,854 1,123 23.6 19.9 20.5 22.4 13.6 397 344 360 348 187 20.4 20.9 21.2 18.8 16.7 12.0106 (0.017) 4,711 3,559 57.0 43.0 990 646 21.0 18.2 10.4755 (0.001) Highest education level of household head No education Primary education Secondary education Higher education Type of place of residence urban rural Household socioeconomic status poorest poorer middle richer richest Household size 7 members and below above 7 members 30 Type of place of residence of the pupil The type of place of residence of the pupil was considered in the study to find out whether it had an impact on pupil absenteeism. The results in Table 4.3 indicated that 6.2 percent of the pupils were from Urban and 93.8 percent from Rural. Table 4.3 indicated that pupil absenteeism was 12.6 percent in urban areas and 20.3 percent in rural areas. Further more, the results in Table 4.3 indicated that the relationship of type of place of residence of the pupil with absenteeism among pupils was highly significant (p=0.000). Household socio-economic status Household socio-economic status was referred to as how rich or poor the pupil’s household was. As indicated in Table 4.3, it was observed that 23.6 percent of pupils came from poorest class, 19.9 percent from poorer class, 20.5 percent from middleclass, 22.4 percent from richer class and 13.6 percent from richest class. From Table 4.3, absenteeism is high to pupils from middle class (21.2 percent), followed by pupils from poorer class (20.9 percent), followed by pupils from poorest class (20.4 percent), followed by pupils from richer class (18.8 percent) and less absent were pupils from richest class (16.7 percent). It was indicated from the chi-square statistic that the relationship between household socio-economic status and absenteeism among primary school pupils was significant (p= 0.017). 4.4 Multivariate analysis A complementary log-log model was fitted to examine the relationship between the absenteeism among primary school pupils and the independent variables. This was done to confirm the results on bivariate analysis. Household size, type of place of residence 31 and disability status of the pupil turned out to be significant; however, household socioeconomic status and sex of household head were not significant as shown by their pvalues in Table 4.4. Table 4.4: Results of the Complementary log-log regression model of absenteeism among primary school pupils according to the independent variables ( Coefficient) Significance RR -0.138 0.008 0.879 0.460 0.001 1.522 Only one disability 0.201 0.015 1.204 Two disabilities 0.728 0.000 1.925 More than two disabilities 0.154 0.595 1.153 Poorest* 0.047 0.521 1.045 Poorer 0.066 0.365 1.063 Middle -0.048 0.515 0.956 Richer -0.090 0.332 0.919 0.093 0.085 1.090 -1.956 0.000 Variable Household size 7 members and below* above 7 members Type of place of residence Urban* Rural Disability status of the pupil No disability* Household socio-economic status Richest Sex of household head Male* Female Constant *Reference category RR = Relative risk 32 Household size Table 4.4 showed that pupils from households with above 7 members were at a reduced risk of absenting themselves from school compared to those ones from households with 7 members and below. This study established that absenteeism among pupils from households with above 7 members was 0.879 times that of those from households with 7 members and below. This is in agreement with study findings of Colclough et al. (2000) which associates increase in household size with reduction in pupil absenteeism. This was statistically significant (p=0.008) and it confirms that absenteeism among primary school pupils is dependent on household size. Type of place of residence The results in Table 4.4 confirmed that there is a significant relationship between the type of place of residence of the pupil and absenteeism among primary school pupils (p=0.001). Pupils that were residing in rural areas were at an increased risk of absenting themselves from school compared to those ones that were residing in urban areas. Absenteeism among pupils residing in rural areas was found to be 1.522 times that of those residing in urban areas. This was in agreement with the findings of UBOS and Macro International inc. (2007) which revealed that the rate of absenteeism is higher in rural areas than in urban areas, however, in disagreement with the findings of Eoghan (2008) which revealed that absenteeism is higher in urban areas than in rural areas. 33 Disability status of the pupil Results in Table 4.4 showed that pupils with all kinds of disabilities were at an increased risk of absenteeism compared to those without any disability. This could be because of the status of persons with disabilities; they are vulnerable and suffer from social exclusion, stigma and discrimination which lead to reduction of their morale of attending school regularly. In this study it was found out that absenteeism among pupils with only one type of disability was 1.204 times that of those without any disability. This was statistically significant (p=0.015). It was also established that the absenteeism among pupils with two types of disabilities was 1.925 times that of those without any disability. This was statistically significant (p=0.000). 34 CHAPTER FIVE SUMMARY OF FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 5.1 Summary of the findings The researcher analyzed the socio-demographic and socio-economic factors assumed to be associated with absenteeism among primary school pupils. The analysis was done at three levels, namely: univariate, bivariate and multivariate analysis. From univariate analysis; it was observed that household heads included in the study majority of them were in the age interval of 30-49, followed by those above 49 years and least were aged less than 30 years. Households included in this study were dominated by those of 7 members and below as compared to those ones with above 7 members. Majority of the pupils came from the poorest households and the least came from the richest households. Pupils from male headed households out weighed those from female headed ones. Most of the household heads had attained primary level of education, followed by those with no education, followed by those with secondary education and few had attained tertiary education level. Majority of the pupils were not orphans, however, single orphans were more than double orphaned ones. The relationship of the pupil to the household head was dominated by sons/daughters to the household head and the least were those pupils who were households themselves. There were more male pupils than females in the study. Majority of the pupils were residing in rural areas. Disability status was dominated by pupils with no disability, followed by those with only one type of disability, two types of disabilities and the least were those with more than two types of disabilities. 35 From the bivariate analysis, it was found out that the variables that had a significant association with absenteeism among primary school pupils were: disability status of the pupil, sex of the household head, type of place of residence, household size and wealth index. These variables had p-valves less than 0.05 and were taken for multivariate analysis. At multivariate analysis, a complementary log-log model was fitted to examine the relationship between the absenteeism among primary school pupils and the independent variables. This was done to confirm the results on bivariate analysis. It was found out that household size, type of place of residence and disability status of the pupil had a significant impact on pupil absenteeism. 5.2 Conclusions The study established that household size, type of place of residence and disability status of the pupil were the significant determinants of absenteeism among primary school pupils in Uganda. Type of place of residence and disability status of the pupil were established to increase the risk of absenteeism among primary school pupils. However, increase in household size was established to reduce the risk of absenteeism among pupils. 5.3 Recommendations Disabled pupils were found to absent from school more than those without any disability. MoES should clearly define the various types of disabilities and sensitize parents/guardians about them so that they can identify these children accordingly and also 36 should encourage parents to accept their children with disabilities the way they are like any other normal child and support them in everything that can enable them to attend school regularly. All schools should ensure that they provide a conducive environment for disabled pupils for participation effectively and friendly service delivery. The MoES should set up centers or schools for disabled students in every county or district, facilitate and equip them with all that is necessary instead of enrolling them in normal schools where their needs are usually neglected. More still the MoES should reinstate the inspectors for special needs (disabilities) so that they carry out inspections to identify disabled students, their unique disability requirements and plan for them accordingly. Pupils residing in rural areas were found to absent themselves from school more than those from urban areas. MoES, NGOs, local authorities/local government (LC III and LC V) and community leaders of all descriptions should strengthen the sensitization of rural parents/guardians on their roles and responsibilities so as to fulfill their primary parental responsibility of monitoring their children’s school attendance, providing them with school requirements and doing everything possible to ensure that their children are regular at school. For example community leaders should take advantage of all solid gatherings like LC meetings, speech days, religious functions, weddings etc to speak about regular attendance of school. In addition, rural pupils should be sensitized on the dangers of absenteeism. 37 5.4 Areas of further research The study employed secondary data that did not follow up pupils’ attendance/absenteeism patterns for a reasonably enough time since data was for only one week, other researchers can carry out a study capturing pupil’s attendance patterns for more than one week, say a year or more. In addition, information on variables like cost of education, distance from household to school which are believed to have an impact on the attendance patterns of pupils were not captured in the data that was used in this study, a further study could address itself to the relationship between pupil absenteeism and cost of education and distance from household to school. 38 References Admassie, A. (2003). Child labour & schooling in the context of subsistence rural economy: can they be compatible? International Journal of Educational Development, 23(2), 167-185. Aikman, S. & Unterhalter, E. (2005). Beyond access: Transforming Policy and Practice for Gender Equality in Education. London: Oxford. Ainsworth, M., Beegle, K. & Koda, G. (2005).The impact of adult mortality and parental deaths on primary schooling in North-Western Tanzania. The Journal of Development Studies, 41(3), 412-439. Al Samarrai, S. & Peasgood, T. (1998). Educational attainments and household characteristics in Tanzania. Economics of Education Review, 17(4), 395-417. Atima, F. (2009). Inspection Report of Primary Schools in Luwero District carried out from 13-24-July 2009. Unpublished report to Ministry of Education and Sports, Kampala, Uganda. Bennell, P., Hyde, K. & Swainson, N. (2002). The Impact of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic on the Education Sector in Sub-Saharan Africa: A synthesis of the findings and recommendations of three country studies. Brighton: University of Sussex. Boyle, S., Brock, A., Mace, J. & Sibbons, M. (2002). Reaching the Poor: The ‘Costs’ of Sending Children to School. Synthesis Report. London: DFID. Case, A. & Ardington, C. (2004). The impact of parental death on school enrolment and achievement: longitudinal evidence from South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town. 39 Chimombo, J., Chibwanna, M., Dzimadzi, C., Kadzamira, E., Kunkwenzu, E., Kunje, D. & Namphota, D. (2000). Classroom, School and Home Factors that Negatively Affect Girl’s Education in Malawi. New York: UNICEF. Colclough, C., Rose, P. & Tembon, M. (2000). Gender Inequalities in Primary Schooling: The Roles of Poverty and Adverse Cultural Practice. International Journal of Educational Development, 20(1), 5–27. Eoghan, Mac Aogáin. (2008). Analysis of School Attendance Data in Primary and PostPrimary Schools, 2003/4 to 2005/6, Report to the National Educational Welfare Board (NEWB). Dublin: Education Research Center. Ersado, L. (2005). Child labor and schooling decisions in urban and rural areas: comparative evidence from Nepal, Peru, and Zimbabwe. World Development, 33(3), 455-480. FAWE Uganda (2004). Sexual Maturation in Relation to Education of Girls in Uganda: documenting good practices in girls’ education. Unpublished report, Kampala: FAWE U. Glick, P. & Sahn, D.E. (2000). Schooling of Girls and Boys in a West African Country: the Effects of Parental Education, Income, and Household Structure. Economics of Education Review, 19(1), 63–87. Grant, M. & Hallman, K. (2006). Pregnancy Related School Dropout and Prior School Performance in South Africa. Policy Research Division Working Paper Number 212, NewYork: Population Council. Guarcello, L., Lyon, S. & Rosati, F. (2004). Orphan hood and Child Vulnerability: Burundi. Understanding Children’s Work Working Paper Number 24, Rome: Understanding Children’s Work (UCW Project). 40 Hazarika, G. & Bedi, A.S. (2003). Schooling Costs and Child Work in Rural Pakistan. Journal of Development Studies, 39(5), 29-64. Hunter, N. & May, J. (2003). Poverty, Shocks and School Disruption Episodes among Adolescents in South Africa. CSDS Working Paper, No. 35. Durban: University of Kwazulu-Natal. Juneja, N. (2001). Primary Education for All in the City of Mumbai, India: The Challenge Set by Local Actors. School Mapping and Local-Level Planning. Paris: UNESCO. Kagolo, F. (2009). Teacher, Pupil Absenteeism Kills Education Standards. http://allafrica.com/stories/200909090191.html (Accessed 2009, November 2nd). Kane, E. (2004). Girls’ Education in Africa: What Do We Know About Strategies That Work? Washington DC: World Bank. Konate, M.K., Gueye, M. & Nseka-Vita, T. (2003). Enrolment in Mali: Types of Household and How to Keep Children at School. Paris: UNESCO. Manuel Crespo (1984). School Absenteeism and Aspirations : A Non-Recursive Passive Path Model(1). http:/www.jstor.org/stable/1500752. (Accessed 2011, August 11th). Mfum-Mensah, O. (2002). Impact of Non-Formal Primary Education Programs: A Case Study of Northern Ghana. Ontario: Comparative and International Education Society (CIES). Ministry of Education and Sports-Uganda (2009). Report on the Rapid Head Count Exercise; Primary and Secondary Schools. Unpublished report, Ministry of Education and Sports-Uganda, Kampala, Uganda. 41 Nakanyike, B., Kasente, D. & Balihuta, A. M. (2003). Attendance patterns and causes of dropout in primary schools in Uganda: a case study of 16 schools. Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR), Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Nekatibeb, T. (2002). Low participation of female students in primary education: a case study of drop outs from the Amhara and Oromia Regional States in Ethiopia. AddisAbaba: UNESCO. Nsubuga, Y.K.K. (2003). Development and examination of secondary in Uganda: Experience and challenges. Kampala, Uganda. Peters, S.J. (2003). Inclusive Education: Achieving Education for All by Including those with Disabilities and Special Needs. Washington DC: World Bank. Porteus, K., Clacherty, G., Mdiya, L., Pelo, J., Matsai, K., Qwabe, S. & Donald, D. (2000). ‘Out of school’ children in South Africa: an analysis of causes in a group of marginalised, urban 7 to 15 year olds. Support for Learning, 15(1), 8-12. Pryor, J. & Ampiah, J.G. (2003). Understandings of Education in an African Village: The Impact of Information and Communication Technologies. London: DFID. Rose, P. & Al Samarrai, S. (2001). Household Constraints on Schooling by Gender: Empirical Evidence from Ethiopia. Comparative Education Review, 45(1), 36-63. Runhare, T. & Gordon, R. (2004). 2004 ZIM: Comprehensive Review of Gender Issues in the Education Sector: New York: UNICEF. The PROBE Team (1999). Public Report on Basic Education in India; The PROBE Team. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 42 The Republic of Uganda (1992). “Education for National Integration and Development.” Government White Paper on the Educational Policy Review Commission Report ( Education White Paper), Kampala, Uganda. UNICEF (2005). Sanitation:the challenge. http://www.childinfo.org/areas/sanitation/.(accessed 2009, November 13th) Uganda Bureau of Statistics (2006). Uganda National Household Survey 2005/2006, Report on Socio-economic Survey. Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and Macro International Inc. (2007). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006.Calverton, Maryland, USA: UBOS and Macro International Inc. Uganda Women’s Effort to Save Children (2008). Communities Causing Positive Change in UPE Implementation, 3,36-42. Zimmerman, F.J. (2003). Cinderella goes to school: the effects of child fostering on school enrollment in South Africa. Journal of Human Resources, 38(3), 557-590. 43