Estra

advertisement

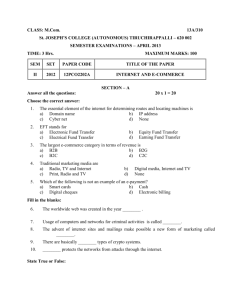

Electronic Commerce, R&D, Externalities, and Productivity An Empirical Study of Taiwanese Manufacturing Firms Jong-Rong Chen* Ting-Kun Liu Graduate Institute of Industrial Economics National Central University, Taiwan and Cliff J. Huang Department of Economics Vanderbilt University, U.S.A. Abstract Using a newly constructed panel data on Electronic Commerce (e-commerce) and R&D investments by Taiwanese manufacturing firms during 1999-2000, this paper investigates the relationship between knowledge capital and productivity. The knowledge spillover consists of R&D spillover and e-commerce network externalities. Furthermore, this paper considers the impact of knowledge capital on capital productivity and labor productivity through substitution by applying a non-neutral production function. The empirical results show that: (1) both e-commerce and R&D capital have positive impact on productivity; (2) e-commerce stock and R&D capital tend to have a complementary relationship; (3) intra-industry e-commerce network externalities and inter-industry R&D spillover demonstrate a more significant contribution to productivity than the other two spillovers. Draft Submitted for Presentation at Asia-Pacific Productivity Conference (APPC), July 14-16, 2004, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia Keywords: Productivity, Taiwanese manufacturing e-commerce network externalities firms, R&D spillover, JEL classification: D24; L60 * Corresponding author, Graduate Institute of Industrial Economics, National Central University, Chungli 320, Taiwan. Tel: +88634227791. Fax: +88634226134. E-mail: jrchen@cc.ncu.edu.tw 1 1. Introduction In the dynamic environment of a knowledge-based economy, firms must try to maintain their advantageous position under extreme competition. According to the neoclassic school theory, preserving the continued growth of long-term technological progression is the essential key to the success of firms. For example, the adoption of a new production technology, new inputs, and other knowledge or inventive factors changes the equilibrium of the market structure (Geroski and Pomroy, 1990; Chen, et al., 2000). In the 1990s Taiwanese manufacturing firms faced a dilemma of lacking the basic level of labor and technological human resources, and they had difficulties in acquiring land as a result of the rise in environmental protection consciousness. In order to hold their competitive advantage, some industries began to move their businesses from Taiwan to Southeast Asia and/or Mainland China, while other industries still staying in Taiwan sought to upgrade their technology and industry. As the global economic situation changes with each passing day, with the progression of information technology (IT), and under the application and diffusion of Internet and e-commerce, the global operational environment has varied greatly. For example, Dewan and Kraemer (2000) quoted a statistical survey by the International Data Corporation (IDC) in 1997, which showed that global IT expenditure increased from $162 billion in 1985 to $630 billion in 1996 and has a continuing rising trend. Starting from basically zero in 1995, total electronic commerce is estimated at some $26 billion for 1997 and predicted to reach $1 trillion in 2003-05 (OECD, 1999). E-commerce growth to date has been quite impressive. For the sake of digesting information to create and accumulate knowledge as soon as possible, and for the purpose of consolidating their competence in competition and globalization, knowledge capital or technological capital has become the focal point and core factors of all industries. To reform products, exploit new products, or improve the process to 2 decrease production costs, firms in Taiwan invest in reasonably large amounts of R&D expenditure. In Table 1 we observe that both R&D expenditure and the number of U.S. patents granted to Taiwanese firms have an increasing trend, and the rank of the number of U.S. patents granted represents the achievement of innovation by these companies. In the era of a knowledge-based economy, firms who want to raise their market share should respond to market demand rapidly. As such, they apply electronic technology to confirm that their commodities are handed over to their clients from the process of ordering, production, and transportation. Therefore, the application of Internet and electronic technologies becomes the firms’ new generation investments and challenges. Table 2 shows the amount of e-commerce and the ratio of e-commerce transaction of Taiwanese manufacturing firms, showing that both magnitudes also have an increasing trend. In view of this, Taiwan’s government encourages firms to engage in R&D and innovation by financing private firms. The island’s government also helps companies to establish an e-commerce environment of integrated supply and demand chain enthusiastically so as to strengthen the integration of up- and down-stream industries, promote industrial productivity and national competition, and reach the future goal of e-business development. Firms face continual and enormous investments in e-commerce and R&D, and they encounter higher risks. Firms also may have difficulties in repairing and operating these technical facilities, including excessive costs, lower cooperative willingness of up- and down-stream industries, and a lack of capability and related technological human resources. Moreover, the economic performance assessment is an important indicator of firms’ investment strategies and is a symbol of success of the authorities’ tax reduction or subsidy policies. Consequently, no matter firms promote e-commerce 3 and R&D investments with help by the government or firms accelerate their own e-commerce and R&D by themselves, it is worth exploring in depth the impact of e-commerce and R&D on productivity. There are a large number of studies that have assessed the contribution of R&D to productivity at the firm level using panel data (e.g. Griliches and Mairesse, 1983; Cuneo and Mairesse, 1984; Griliches, 1986; Goto and Suzuki, 1989; Mairesse and Sassenou, 1991; Lichtenberg and Siegel, 1991; Hall and Mairesse, 1995; Mairesse and Hall, 1996; Branstetter and Chen, 1999; Yang et al., 2001; Yang and Chen, 2002). Most of them show that knowledge capital and R&D expenditure do actually have a significant positive impact on productivity. Despite the daily attention to the knowledge-based economy, many economists have claimed that e-commerce is a manifestation of the Internet and related technical progress, and e-commerce will dramatically reduce transaction costs and lead to a growth in productivity and economy through shifting the production frontier and/or increasing returns (Romer, 1986; Grossman and Helpman, 1991; Ajit, 1995; Aghion and Howitt, 1998 Lucking-Reiley and Spulber, 2001). However, there is surprisingly little empirical evidence on the impact of e-commerce on firms’ productivity. With respect to research on e-commerce and productivity, Oliner and Sichel (2000) adopted “back of the envelope” calculations to explore the impact of e-commerce on productivity in the U.S. during 1996-99, finding that e-commerce has no significant impact on MFP growth. Litan and Rivlin (2001) used “judgmental estimates” and showed the Internet’s contribution to productivity growth to be 0.2-0.4% per year over the last half of the 1990s. Goss (2001) examined the impact of actual Internet usage by industry for 1997-1999 by using pooled time-series and cross-section data, using job-related Internet usage as a proxy variable. Goss suggested that job-related Internet usage has a positive and statistically significant impact on productivity growth of 4 roughly 0.25% per year. Konings and Roodhooft (2002) made use of a large representative data set of Belgium firms to study empirically the impact of e-business on productivity and cost efficiency of firms. They concluded that e-business had no effect on productivity in small firms, but selling online and e-procurement both had positive effect on productivity in large firms. In these studies mentioned above, there is little empirical evidence on the impact of e-commerce on productivity, because e-commerce is a recent and rapidly evolving phenomenon and the measurement of e-commerce is difficult (Fraumeni, 2001). The above empirical studies implemented input-side Internet usage (Goss, 2001), indirect variable (Oliner and Sichel, 2000), or a dummy as a proxy of e-business or e-commerce (Konings and Roodhooft, 2002). However, Internet usage prompts problems of measurement and quantification, and the application of electronic technology is comprehensive and not limited to Internet.1 In addition, Internet usage and dummy variables obviously cannot be ample enough to reflect the empirical dynamic situations of firms that engage in e-commerce investment. Therefore, this paper adopts an output-side indicator of e-commerce transaction as a proxy of e-commerce, which would be a proper and alternative way to measure the impact of e-commerce. Romer (1986) considered that knowledge enables a firm or an industry to successfully adopt advanced technology that will naturally spill over to other firms or industries. Carlsson (1997) suggested that the most important features of technological systems are the characteristics of knowledge and spillover mechanisms, which determine the potential spillovers. 2 There are two types of network 1 For details, please see Table 2: Procurement and sale via e-mail and Internet in Taiwan, Table 3: Electronic technologies adoption in Taiwan, and Table 4: The ways of communication between manufacturers and up and down-stream partners. 2 Carlsson (1997) defined the technology systems as factory automation, electronics and computers, biotechnology, and power technology. 5 externalities, direct and indirect effect. The direct network effect comes from an increase in users, while the indirect effect comes from the development of applications (Katz and Shapiro, 1985; Mun and Nadiri, 2002). Therefore, another feature of e-commerce capital that distinguishes it from other traditional inputs is that it may generate considerable economic externalities. When the number of firms engaged in e-commerce and the items of electronic technologies adoption from firm i’s related industries are increasing, this could be helpful for firm i to enhance productivity. For instance, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has proposed the concept of Virtual Fab, whereby TSMC can move its wafer factory into IC clients’ backyards via the Internet. More than 500 clients of TSMC through the TSMC-Online platform can trace the percentage of scheduled progress and an analysis of defects. This mechanism also helps them to save production costs and shorten the product’s time to enter the market. Consequently, we place more emphasis on the network externalities of e-commerce in our empirical model. Most analyses of the impact of e-commerce and/or R&D on productivity focus on manufacturing firms in developed economies, such as the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Similar studies on this issue in newly industrialized economies (NIEs) have been scarce, and they neither estimate the impact of e-commerce and R&D on productivity simultaneously nor apply firm-level panel data to detect this issue. Hence, the result from Taiwan’s experience could be a consultation for other developing countries. In order to understand the impact on productivity of the rapid increase in e-commerce and R&D spending in recent years, this paper use a newly constructed panel data of Taiwanese manufacturing firms during 1999-2000. We investigate the relationship between knowledge capital (including both e-commerce and R&D investments) and productivity with the consideration of externalities. We also employ an output-side indicator of e-commerce transaction to construct e-commerce stock. 6 Furthermore, this paper considers the impact of knowledge capital on capital productivity and labor productivity through substitution by applying a non-neutral production function.The Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) approach is robust in the presence of heterocedasticity across firms and the correlation of disturbances within firms over time, and it is adopted to acquire more efficient estimators in this paper. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Sections 2 and 3 present the empirical models and data sources. In Section 4 we analyze the econometric results. Conclusions are in Section 5. 2. Empirical framework and measurement of spillover stocks The framework in which we measure the contribution of e-commerce and R&D to productivity follows the standard approach to analyze the contribution of R&D to productivity. This paper assumes that the production function can be approximated by a Cobb-Douglas function: Yit Aet CAPit LABit KNOit e it , (1) where Y is value added, CAP, LAB, and KNO are the physical capital, labor input, and knowledge capital, respectively, and knowledge capital consists of firms’ own e-commerce stock (ECS) and R&D stock (RDS). The subscripts i and, t refer to the firm i and the current year t, while λ is the rate of disembodied exogenous technical change andεis the error term reflecting the effect of unknown factors and other disturbances.3 If the investment decisions on e-commerce and R&D are independent, then 3 The time trend t will be replaced with time dummies in estimation. 7 equation (1) can be written as: Yit Aet CAPit LABit ECSit RDS it e it . (2) We can take logarithms to equation (2) and obtain the linear regression to implement the estimation of the Cobb-Douglas function as shown below: yit a t capit labit ecsit rdsit it , (3) where the lower-case letter denotes the logarithms of variables, and , , and especially and (the elasticity of value added with respect to e-commerce and R&D) are the parameters of interest. According to Kambil (1995), firms use the Internet to improve innovation, production, sales, and service processes. Kambil noticed that as universities and firms increasingly go online with working papers, technical reports, and journal articles, individuals have instant access to relevant materials to support research and innovation, and information about innovations or innovations themselves can be distributed in a matter of minutes. Madden and Coble-Neal (2002) indicated the emergence of e-commerce driven by this net adoption of Internet services and continual technological innovation. This implies that the behavior for firms to invest in e-commerce and R&D activities is not only for industrial transition and government policies, but also for the reason of relative technological application connections. In accordance with previous studies and surveys, the decisions to invest in e-commerce and R&D investments by firms can be influenced interactively. Therefore, this paper releases the restriction of independence between e-commerce and R&D investments, and we allow this relationship to be a substitute or a complement. Thus, the knowledge capital KNOit should be a function including the stock of accumulated past e-commerce and R&D investments. Because e-commerce and R&D investments may generate considerable economic 8 externalities, such as knowledge spillovers and network externalities, the exogenous variations of spillovers can influence the decision of firms’ and have an impact on productivity. When the effect of knowledge spillovers on firm i from external sources is taken into account, it is partly determined by firms and serves as an endogenous variable (Adams, 2000). Therefore, we take account of spillovers of e-commerce and R&D into our model, and we can express KNOit as follows: KNOit f ( ECSit , RDS it , KSit ) , (4) where KSit is the stock of spillover. To account for the different abilities of firms to internalize other firms’ knowledge, equation (4) is extended by adding weights, wij, which stands for firm i’s ability to internalize pieces of firm j’s knowledge stock. The larger these weights are, the more firm i can gain from firm j’s knowledge stock. Bernstein (1988) provided the following indicator: N KSi wij K j , j i (5) where wij represents firm i’s ability to absorb firm j’s knowledge stock, and K j is the knowledge stock for firm j.. This paper follows the work of Chen and Lu (2002) to construct two types of R&D spillover stocks - Rstra and Rster. Term Rstra represents the intra-industry R&D spillover, while Rster represents the inter-industry R&D spillover by using the following definitions, respectively: N Rstrai wi1RDS j (6) j i N Rsteri wi 2 RDS j , (7) j i where wi1 is the ratio of firm i’s R&D expenditure to firm i’s 4-digit industry’s total R&D expenditure and wi 2 is the R&D expenditure of firm i’s 4-digit industry’s total 9 R&D expenditure to firm i’s 2-digit industry’s total R&D expenditure.4 In order to take into consideration the effect of e-commerce network externalities, we modify the of model Chen and Lu (2002) to construct two types of e-commerce network externalities stocks. Term Estra represents the intra-industry e-commerce network externalities, while Ester represents the inter-industry e-commerce network externalities by using the following definitions, respectively: N Estrai ni1ECS j , ni1 dei1 iei1 (8) i j N Esteri ni 2 ECS j , ni 2 dei 2 iei 2 , (9) i j where ni1 is the weight of intra-industry network externalities, and is composed of two effect: 1) direct effect dei1 is the ratio of the number of firms engaging in e-commerce of firm i’s 4-digit industry to the total number of firms in firm i’s 4-digit industry. 2) indirect effect iei1 is the ratio of firm i’s electronic technology application index to firm i’s 4-digit industry’s total electronic technology application index. 5 Term ni 2 is the weight of inter-industry network externalities and is composed of two effect: 1) direct effect dei 2 is the ratio of the number of firms engaging in e-commerce in firm i’s 4-digit industry to the number of firms engaging in e-commerce in firm i’s 2-digit industry. 2) indirect effect iei 2 is the ratio of firm i’s 4-digit industry’s total electronic technology application index to firm i’s 2-digit industry’s total electronic technology application index. Since each of these elements interacts with one another, these interactive effect and the specific functional form of KNOit are unknown. Here we take the Tornquist input 4 Chen and Lu (2002) used a 2-digit industry instead of a 3-digit one to avoid the estimation problems due to similarity among industries. 5 Firm i’s electronic technology application index is measured by the ratio of the number of items of electronic technology application that firm i has adopted to the total number of items of electronic technology application in our survey data. Please see Table 3 for details on items of electronic technology application. 10 value index to construct the KNOit index for our empirical model as follows: KNOit [( X 1it )1 ( X 2it ) 2 ( X 3it )3 ( X 4it ) 4 ( X 5it )5 ( X 6it )6 ( X 7 it )7 ] (10) where X1 ~ X 7 denotes ECS, RDS, ECS RDS , Estra, Ester, Rstra, and Rster, respectively. i is the share of each variable of knowledge capital in the total value of the knowledge capital bundle. Besides, intensive use of knowledge capital is likely to raise the capital (CAP) productivity and labor (LAB) productivity through substitution (Lucking-Reiley and Spulber, 2001). Therefore, the end result to production is a non-neutral shift of observed output; not only will productivity of inputs change, but also will the marginal rate of technical substitution (Huang and Liu, 1994). In this paper we apply a non-neutral production function different from the conventional model of equation (1). Our reformation of non-neutral production function is the following: Yit Ae1t 2 knoit CAPit1 2 knoit LABit1 2 knoit e it (11) Taking logarithms to equation (11) we obtain equation (12), which can be used to implement the relationship between knowledge capital and productivity. yit a 1t 2 knoit 1capit 2 knocapit 1labit 2 knoitlabit it (12) Equation (12) will be explored in this paper, and the general specification of equation (3) will also be discussed in our study for comparison. In order to investigate the impact of related variables of knowledge capital on productivity, we use the estimated coefficients of equation (12) to calculate the partial average productivity (PAP) in the following way: PAPi yi( 2 ) yi(1) X i (t ) X i (t 1) (13) where yi(1) and yi( 2 ) are the output contribution of variables i at time t-1 and t respectively while holding other variables constant, X i ’s are defined in equation 11 (10). On investigating the relationship between knowledge capital and productivity, as is common with panel data, we allow for the existence of individual effect which are potentially correlated with the right-hand side regressors, such that: it vit ui , (14) where, ui is a firm effect that corresponds the permanent, unobserved heterogeneity across firms, but not within a firm over time, and vit is a “white noise” error term, representing a period-specific stock for firm i that is assumed to be independent across firms and over time. Using a “within firm” panel estimator is a standard method to eliminate the individual effect (Yang et al., 2001). Mairesse and Hall (1996) and Yang et al. (2001) studied the relationship between knowledge capital and productivity. They proved that the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) is better in robustness in the presence of heteroskedasticity across firms and a correlation of disturbances within time. It can also be efficient even under a weak assumption on the disturbance. Therefore, this paper adopts the GMM developed by Arellano and Bond (1991) and Ahn and Schmidt (1992). 3. Data sources and variable definitions Owing to a lack of integrated data about e-commerce, R&D, and related firms’ operational information in Taiwan, this paper merges the automation and e-commerce survey and the plant survey of Taiwanese manufacturing firms during 1999-2000 provided by MOEA to obtain a more complete database. At the same time, taking into account the representation of industrial distribution and the length of time period, we construct a balanced panel data of 3,698 Taiwanese manufacturing firms for the survey period of 1999-2000. In equation (2) of this paper, due to materials not included in the model, we use 12 value-added (VAL) as the proxy variable of dependent variable Y. According to MOEA’s definition, we measure VAL by the following specification: VAL is equal to total output sales subtracting intermediate inputs. Total output sales have been deflated using a wholesale price index and intermediate inputs have been deflated using a price index of intermediate inputs. With respect to the explained variables of the right-hand side equation, physical capital (CAP) is total fixed capital and we use a capital price index to adjust for inflation, where labor (LAB) is the number of workers. Internet usage incurs problems of measurement and quantification, and the application of electronic technology is comprehensive and not limited to the Internet.6 In addition, Internet usage and dummy variables obviously are not ample enough to reflect the empirical dynamic situations of firms engaging in e-commerce investment. Therefore, this paper adopts an output-side indicator of e-commerce transaction as a proxy of e-commerce. Furthermore, e-commerce stock (ECS), R&D stock (RDS), and spillover stock (KS) are used to construct knowledge capital. Our measurements of e-commerce and R&D stocks follow that of Mairesse and Hall (1996) and Yang and Chen (2002). They define the equation of knowledge capital stock as follows: K t I t (1 ) I t 1 (1 ) 2 I t 2 , (16) where K represents the e-commerce and R&D stocks, I is e-commerce transaction or R&D expenditure, and is the depreciation rate. Because of the limitation of the survey period, this paper adopts only one lagged year to construct knowledge capital stock. We assume that the above knowledge capital stocks have a constant depreciation rate of 15%, according to the general setting of previous papers.7 6 For details, please see Table 3: Procurement and sale via e-mail and Internet in Taiwan, Table 4: Electronic technologies adoption in Taiwan, and Table 5: The ways of communication between manufacturers and up- and down-stream partners. 7 Please see Hall and Mairess (1995), Hall and Mairess (1996), Yang et al. (2001), Yang and Chen 13 As for the spillover effect, this paper considers the spillover effect of intra-industry and inter-industry. The total (e-commerce or R&D) spillover effect is the sum of intra-industry spillover effect (Estra or Rstra) and inter-industry spillover effect (Ester or Rster). We apply equations (6)-(9) to estimate intra-industry and inter-industry spillover effect. Table 5 gives sample statistics for our key variables. 4. Empirical results In this section we present the results of the impact of e-commerce and R&D activities on productivity, which were achieved by applying GMM. The previous equation (2) is considered as the starting point of the analysis.8 We separate equation (2) into two estimative modes: mode (i) is a regression under the assumption that e-commerce and R&D activities are independent (i.e. equation (3) of this paper); and mode (ii) is a regression that releases the restriction of e-commerce and R&D activities being independent, and it subsumes the e-commerce and R&D spillover effect of intra-industry and inter-industry under consideration, and we use those variables to construct the knowledge capital (i.e. equation (12) of this paper). This paper tests the over-identifying restrictions by the Hansen J statistic, which is consistent in the heteroskedasticity presence. The test results of all modes do not reject the validity of instruments, as indicated by accepting the null hypothesis with a p-value above 0.05. The empirical results are presented in Table 6. The second column of Table 6 shows the empirical results of mode (i), where the labor coefficient is higher than the capital coefficient, and they both have significant impact on productivity level. The first kind of knowledge capital, e-commerce stock (2002), and Chen and Lu (2002). This paper also tries to use other depreciation rates (20% and 30%) to construct knowledge capital stocks, and we find that there is no significant difference between empirical results. 8 In this estimation we use all independent variables and all lagged capital as instruments. 14 logECS and its parameter is positive significance at the 1% statistical level (the coefficient of e-commerce stock elasticity is 0.032). This provides evidence that Taiwanese firms devoting more e-commerce investment efforts have a better productivity performance, and this result is consistent with Konings and Roodhooft (2002), Litan and Rivlin (2001), and Goss (2001) in their findings. Goss suggested that job-related Internet usage had a positive and statistically significant impact on productivity growth of roughly 0.25% per year. This implies that there is considerable room for productivity promotion for Taiwanese firms to invest in electronic activities in order to construct a better e-business and/or e-commerce environment. We also explore another important knowledge capital, R&D stock, and detect the impact of R&D stock on productivity. The result shows that the coefficient of R&D stock logRDS is 0.203, and the estimated R&D stock contribution to productivity is on the high end of Mairesse and Sassenou (1991) and Mairesse and Hall (1996). Their estimated R&D stock elasticity range of 0.008-0.210 in developed countries. This magnitude is also higher than the average R&D elasticity of 0.036 for Taiwanese manufacturing firms in 1990-1997 as conducted by Yang and Chen (2002). This reveals that the contribution to productivity by investing in R&D activities by Taiwanese manufacturing firms is not inferior to those advanced countries. The above results have positive and constructive meanings to inspire Taiwan’s government to encourage and assist firms in investing and popularizing e-commerce and R&D activities. The third column of Table 6 presents the estimates of the non-neutral production function of mode (ii). In order to investigate whether knowledge capital has influence on productivity, we use the F-test to test the joint null hypothesis about the parameters in this non-neutral production function model. The joint null hypothesis is H0: 2 2 2 0 , and the alternative hypothesis is H1: 2 0 , 2 0 , or 2 0 , or 15 all are nonzero. Since F=16.55 and P-value <0.01, we reject H0 and conclude that at least one of them is not zero, and thus knowledge capital has an effect upon productivity. In the third column of Table 6, we find that all coefficients of parameters are significance at the 5% statistical level. In order to investigate the impact of knowledge capital on productivity of mode (ii) further, this paper estimates the partial average productivity of each variable of knowledge capital. The results of the partial average productivity estimates are shown in Table 7. With respect to the empirical results of the relationship between e-commerce stock and productivity, we find that partial average productivity of e-commerce stock is small than the contribution of R&D stock toward output. The magnitude of partial average productivity of e-commerce stock is approximately 0.045%, while the partial average productivity of R&D stock is 0.272%. The gap between R&D contribution to productivity and e-commerce contribution could be the reason why Taiwanese firms did not widely adopted electronic technologies and the popularization of e-commerce is not so common among all industries.9 In addition, many of the external benefits from e-commerce, including automation of transaction, cost saving, added convenience and reorganization of firms, that will gain productivity and are not properly showed in the productivity statistics (Litan and Rivlin, 2001; Lucking-Reiley and Spulber, 2001). Given the low usage rate of e-commerce activities, and the huge amount of e-commerce transaction, there exists significant room for enhancing productivity through a substantial expansion in e-commerce activities. Therefore, just as Fraumeni (2001) mentions that although at this point e-commerce may represent a relatively small percentage of both B2B and B2C, its future size and impact on 9 For example, the ratio of the number of firms that invest at least in one survey year in e-commerce to the total number of observations is approximately 14.5% in our data set. 16 e-business process and economic growth may be large. Moreover, the sign of partial average productivity for the interaction effect between e-commerce and R&D stock is positive, implying that e-commerce and R&D activities tend to have a complementary relationship in the production of knowledge during the period of our study. We can infer that R&D and e-commerce activities could integrate with each other to improve productivity, and this finding also intensifies the credibility of our model’s setting. As for the spillover effect, the intra-industry e-commerce network externalities have played a more important role than the inter-industry e-commerce externalities in terms of their impact on productivity. Its partial average productivity is 2.657% as shown in Table 7. On the other hand, the inter-industry R&D spillover has a greater contribution to productivity than the intra-industry R&D spillover. We also find that e-commerce network externalities and R&D spillover have more significant impact on productivity than e-commerce and R&D stocks. This connotes that some studies may overestimate the impact of the knowledge capital of productivity when they neglect the consideration of putting e-commerce and R&D spillover effect into their model. Our empirical finding verifies the claim of Carlsson (1997) that the most important features of technological systems are the characteristics of knowledge and spillover mechanisms. 5. Conclusion Over the past decade, quite a few studies have adopted R&D as the proxy variable of knowledge capital in order to explore the relationship between knowledge capital and productivity. Nevertheless, knowledge capital is not restricted to R&D activities only; e-commerce activities also show a link to knowledge capital. For this reason, this study uses a newly constructed panel data on e-commerce and R&D investments of 17 Taiwanese manufacturing firms during 1999-2000 to investigate the impact of R&D and e-commerce on productivity. The knowledge spillover consists of R&D spillover and e-commerce network externalities. Furthermore, this paper considers the impact of knowledge capital on capital productivity and labor productivity through substitution by applying a non-neutral production function. The empirical results of this study indicate that: (1) both e-commerce and R&D capital have positive impact on productivity; (2) e-commerce stock and R&D capital tend to have a complementary relationship; (3) intra-industry e-commerce network externalities and inter-industry R&D spillover demonstrate a more significant contribution to productivity than the other two spillovers. This means that a firm’s productivity is not only affected by self-owned inputs, but also affected by the technological knowledge diffusion from up- and downstream firms or the same industry. Finally, our empirical results would be a good reference for other developing countries. For further studies, the decomposition of e-commerce transaction into sales and procurement (i.e. e-sales or e-procurement), and the relationship between knowledge capital and spillover variables could be discussed in a detailed and accurate way in the future if a more detailed data were available. References Adams, James D. (2000) “Endogenous R&D Spillovers and Industrial Research Productivity,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, No. 7484. Aghion, Philippe and Peter Howitt (1998) “Endogenous Growth Theory,” MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Arellano, Manuel and Stephen Bond (1991) “Some Tests of Specification for Panel 18 Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations,” Review of Economic Studies, April 1991, 58 (2), 277-97. Ahn, Seung C. and Peter Schmidt (1992) “Efficient Estimation of Panel Data with Exogenous and Lagged Dependent Regressor,” Journal of Econometrics, 68, 5-27. Basant, Rakesh and Brian Fikkert (1996) “The Effect of R&D, Foreign Technology Purchase, and Domestic and International Spillovers on Productivity in Indian Firms,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(2), 187-99. Bernstein, Jeffrey I. (1988) “Costs of Production, Intra- and Inter-industry R&D Spillovers: Canadian Evidence,” Canadian Journal of Economics, 21 (2), 324-47. Branstetter, Lee G. and Jong-Rong Chen (1999) “The impact of technology transfer and R&D on productivity growth in the Taiwanese electronics industry: Microeconometric analysis using plant-level data” Paper presented at the international conference on the role of technology transfer in East Asian economic growth, University of California at Davis, U.S.A. Carlsson, Bo (1997) “On and Off the Beaten Path: The Evolution of Four Technological Systems in Sweden,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, 15 (6), 775-99. Chamberlin, G. (1984) “Panel Data, in Z. Griliches and M. Intriligator eds.,” The Handbook of Econometrics, Volume II, Amsterdam, North Holland. Chen, Jong-Rong, Chih-Hai Yang and Wen-Nueng Cheng (2000) “The diffusion of Multiple Technologies-Evidence from CNC and CAD/CAM,” Journal of Social Science and Philosophy, 12(3), 433-457. Chen, Jong-Rong and Wen-Cheng Lu(2003) “Effect of R&D Spillover on Firm Growth- The Case of the Electronics and Electrical Machinery Industry in 19 Taiwan,” paper presented at the WEAI meeting in Denver, USA. Cuneo, Philippe and Jacques Mairesse (1984) “Productivity and R&D at the Firm Level in French Manufacturing,” R&D, Patents, and Productivity, NBER Conference Report. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press 375-92. Dewan, and K. L. Kraemer (2000) “Information Technology and Productivity: Evidence from Country-Level Data,” Management Science, 46:4, 548-562. Fraumeni, Barbara M. (2001) “E-Commerce Measurement and Measurement Issues,” American Economic Review, 91 (2), 318-22. Geroski, Paul A. and Richard Pomroy (1990) “Innovation and the Evolution of Market Structure,” The Journal of Industrial Economics, 38: 3, 299-314. Goss, Ernest (2001) “The Internet’s contribution to U.S. Productivity Growth,” Business Economics, 32-42. Goto, Akira and Kazuyuki Suzuki (1989) “R&D Capital, Rate of Return on R&D Investment and Spillover of R&D in Japanese Manufacturing Industries,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 71 (4), 555-64. Grossman, Gene M. and Elhanan Helpman (1991) “Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy,” MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Griliches, Zvi (1986) “Productivity, R&D, and the Basic Research at the Firm Level in the 1970's,” American Economic Review, 76 (1), 141-54. Griliches, Zvi and Jacques Mairesse (1983) “Comparing Productivity Growth: An Exploration of French and U.S. Industrial and Firm Data,” European Economic Review, 21(1-2), 89-119. Hall, Bronwyn H. and Jacques Mairesse (1995) “Exploring the relationship between R&D and Productivity in France Manufacturing Firms,” Journal of Econometrics, 65, 263-293. Huang, J. Huang and Jin-Tan Liu (1994) “Estimation of a Non-Neutral Stochastic 20 Frontier Production Function,” The Journal of Productivity Analysis, 5, 171-180. Kambil, Ajit (1995) “Electronic Commerce: Implications of the Internet for Business Practice and Strategy,” Business Economics, 30 (4), 27-33. Katz, Michael L. and Carl Shapiro (1985) “Network Externalities, Competition, and Compatibility,” American Economic Review, 75(3), 424-40. Konings, Jozef and Filip Roodhooft (2002) “The Effect of E-Business on Corporate Performance: Firm Level Evidence,” De Economist, 150 (5), 569-81. Lichtenberg, Frank R. and Donald Siegel (1991) “The Impact of R&D Investment on Productivity-New Evidence Using Linked R&D-LRD Data,” Economic Inquiry, 29 (2), 203-29. Litan, Robert E. and Alice M. Rivlin (2001) “Projecting the Economic Impact of the Internet,” American Economic Review, 91(2), 313-317. Lucking-Reiley, David and Daniel F. Spulber (2001) “Business-to-Business Electronic Commerce,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(1), 55-68. Madden, Gary and Grant Coble-Neal (2002) “Internet Economics and Policy: An Australian Perspective,” The Economic Record, 78 (242), 343-357. Mairesse, Jacques and Bronwyn Hall H. (1996) “Estimating the Productivity of Research and Development in French and United States Manufacturing Firms: An Exploration of Simultaneity Issues with GMM Methods,” International productivity differences: Measurement and explanations, Amsterdam, North-Holland, 233, 285-315. Mariesse Jacques and Mohamed Sassenou (1991) “R&D and Productivity: A Survey of Econometric Studies at the Firm Level,” Science-Technology Industry Review, 8, 317-348. Mun, Sung-Bae and M. Ishaq Nadiri (2002) “Information Technology Externalities: 21 Empirical Evidence from 42 U.S. Industries,” NBER Working Paper, No. w9272, 1-43. OECD (1999) “Growth of Electronic Commerce: Present and Potential,” The Economic and Social Impact of Electronic Commerce, Preliminary Findings and Research Agenda, 27-54. Oliner, Stephen D. and Daniel E. Sichel (2000) “The Resurgence of Growth in the Late 1990’s: Is Information Technology the Story?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(4), 3-22. Romer, Paul M., (1986) “Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth,” Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002-37. Wong, Poh-Kam and Phyllisis M. Ngin (1997) “Automation and Organizational Performance: The Case of Electronics Manufacturing Firms in Singapore,” International journal of Production Economics, 52(3), 257-268. Yang, Chih-Hai and Productivity-Evidence Jong-Rong from Chen Taiwanese (2002) “R&D, Manufacturing Patents Firms,” and Taiwan Economic Review, 30 (1), 27-48. Yang, Chih-Hai, Jong-Rong Chen and Lee G. Branstetter (2001) “Technology Sourcing, Spillover and Productivity: Evidence from Taiwanese Manufacturing Firms,” Paper presented at the 28th EARIE Conference, Dublin, Ireland. 22 Table 1: R&D and Patents of Taiwan (1998-2002) (Million US$) R&D Total Government Budget R&D /GDP Number of U.S. Patents Expenditures Appropriations for R&D (%) Granted and the Rank 1998 8,600.3 NA 1.97 3,100 (7) 1999 9,616.8 NA 2.05 3,693 (5) 2000 10,326.0 3,336.4 2.05 4,667 (4) 2001 11,014.2 3,519.4 2.16 5,371 (4) 2002 12,246.6 4,313.7 2.30 5,431 (4) Source: Main Science and Technology Indicators, 2003, OECD, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, and Intellectual Property Office, MOEA. Note: Number of U.S. patents granted and the rank exclude new designs. Table 2: Procurement and Sales via E-mail and Internet in Taiwan (2001-2002) Procurement Sales via via e-mail e-mail (billion NT$) (billion NT$) Procurement via e-mail Sale via e-mail / / total procurement total sales revenue expenditure(%) (%) 2001 1,699 2,539 6.51 5.97 2002 2,140 3,177 7.39 6.81 Procurement Sales via via Internet Internet (billion NT$) (billion NT$) Procurement via Internet Sales via Internet / / total procurement expenditure(%) total sales revenue (%) 2001 903 2,095 3.46 4.93 2002 1,741 2,747 6.01 5.89 Source: The survey of automation and e-commerce of manufacturing firms during 1995-2002, The Department of Statistics, a staff unit of the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA). 23 Table 3: Electronic Technologies Adoption (2002) (Multiple Choice, %) Metal and Information and Chemical Total Engineering Electronics Industries Industries Industries Network construction 63.98 ERP 59.02 Civil Industries 57.39 70.52 58.54 64.90 59.85 67.70 54.74 43.71 SFCS 37.79 31.28 35.11 42.28 47.02 PDM 32.48 35.71 36.59 25.47 27.48 EDI 27.91 30.54 32.44 22.22 21.19 ASP 21.00 20.44 21.04 18.70 24.50 CRM 16.27 15.27 17.48 15.45 15.89 SCM 15.58 19.21 17.33 10.84 12.58 E-marketplace 8.62 9.85 8.74 6.78 8.94 Other 0.29 0.49 0.30 0.27 0.00 Note: Network contains Internet, Intranet, and Extranet construction and management. ERP means enterprise resource planning, SFCS means shop floor control system, PDM means product data management, EDI means electronic data interchange, ASP means application service provider, CRM means customer relations management, and SCM is supply chain management. Source: The same as Table 2. Table 4: The Methods of Communication Between Manufacturers and Up- and Down-stream Partners (Multiple choice, %) Total Metal and Engineering Industries Information and Electronics Industries Chemical Industries Civil Industries 2000 E-mail 2002 92.47 91.76 90.77 87.72 95.77 96.39 92.73 89.16 89.14 89.40 2000 EDI 2002 2000 Internet 2002 23.52 24.73 39.39 57.80 25.68 25.93 37.39 57.31 27.88 25.41 43.85 61.07 19.39 25.30 37.58 53.49 17.57 20.63 36.74 55.59 Source: The same as Table 2. 24 Table 5: Statistics on Variables (After Deflation), 1999-2000 (Million NT$) Variable Name Mean (S.E.) Value added Capital stock Number of employees E-commerce stock R&D stock E-commerce network externalities stock of intra-industry E-commerce network externalities stock of inter-industry VAL CAP LAB ECS RDS Estra 418.026 (1864.660) 1,032.440 (6863.457) 177.186 (394.483) 132.274 (2450.291) 29.398 (199.031) 713.670 (66.289) Ester 2,689.660 (8280.890) R&D spillover stock of intra-industry R&D spillover stock of inter-industry Rstra Rster 20.858 (123.067) 288.356 (1022.265) Note: The numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Table 6: Estimate of the Empirical Model (1999-2000) (i) (ii) log ECS log RDS 0.0326 a 0.2030 a log CAP log LAB logKNO logKNO log CAP logKNO log LAB constant t R2 0.1271 a (0.0277) 0.7090 a (0.0573) (0.0125) (0.0264) 0.882 0.2881a (0.0125) 0.8365a (0.0200) 0.0380a (0.0084) -0.0010b (0.0023) -0.0058 b (0.0036) -3.3563a (0.8860) 0.0318a (0.0100) 0.855 Note: 1. The numbers in parentheses are standard errors. 2. a, b, and c represent the 1%, 5%, and 10% significant levels, respectively. 25 Table 7: Partial Average Productivity of knowledge capital Partial Average Productivity (%) ECS RDS 0.045 0.272 0.181 2.657 1.362 0.174 1.379 ECS RDS Estra Ester Rstra Rster 26